Abstract

Peer support workers are increasingly considered an essential ingredient in recovery-oriented mental health services. While research continues to point to promising results concerning the ability of these workers to positively impact service users’ experience of hope, quality of life and even health, peer support workers have only recently been introduced in Sweden and the aim of this study was to investigate service users’ experience of receiving peer support in Swedish mental health services. The results were described with three main themes corresponding to three levels of focus from the service user perspective; experience-based knowledge, competence and non-judgmental awareness (individual level), peer support as impacting the relationship with the caring environment (organizational level), and awakening hope for a life beyond the illness (community level). The results suggest the addition of peer support workers as contributing not just to individual outcomes, but to a more trusting relationship to Swedish psychiatric services, which are often considered to work primarily from a medically oriented treatment paradigm.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

At a time when health care services are moving in the direction of person-centered care, with participation and self-determination in focus, there is increasing evidence that people in recovery from serious mental illness have the potential to contribute as uniquely qualified personnel [1]. Peer support workers, with their own “lived experience” of having utilized mental health services, and trained in using this experience to support individuals struggling in various phases of their illness, are now considered as essential in a recovery-oriented mental health work force and the subject of emerging international research [2, 3].

Peer support involves people in recovery from mental illness who are trained and employed to offer support to others using psychiatric services due to mental health problems [4]. Walker et al. [5] found, in a metasynthesis of qualitative studies on peer support, that service users experience these workers as contributing to hope regarding possibilities for recovery, expanded social networks and improved illness management skills. The peer support workers were also viewed as role models for recovery and regarded as easy to build rapport with [5, 6]. Other positive outcomes suggested in the literature [4] include increases in quality of life, empowerment, functioning [7,8,9], sense of control and community belonging [10], improved social integration [5, 11] and self-efficacy [12], all essential components in recovering from mental illness. Other studies suggest a diminished need for mental health services, reduced substance abuse, fewer hospitalizations, and decreased levels of depression and psychosis [10, 13].

Research on peer support has not succeeded however, in proving that the effects of peer worker provided services differ significantly from those provided by ordinary staff, and has yet to demonstrate that the positive tendencies described in the literature can be confirmed in practice [3]. It has been suggested that various models of peer support, the various roles attached to the function, and the complications attached to studying this innovation within complex and varied organizational models, can complicate attempts to produce good quality studies that focus on effects [1, 14, 15]. While many studies point to possible benefits of peer support, others suggest that greater understanding of the expected impact is needed, and that more rigorous research to determine best practice, relevant measures and primary outcomes should be a goal [3]. Davidson and his colleagues suggest that a “third generation” of studies is now underway, studies that attempt to further discern whether the active ingredients of peer support constitute a unique form of service delivery, while earlier research focused on feasibility or comparisons between peer and non-peer staff. Implementing peer support services as a unique contribution in organizations can radically challenge cultures in mental health settings as well [10].

While the introduction of peer support has proceeded slowly in Sweden, possibly due to a dominant medical paradigm in psychiatry, trained peer support workers are now being introduced in Swedish mental health services within in a number of pilot projects. The introduction of peer support in Swedish mental health care may be seen as an innovative and important step in the development of Swedish psychiatry and research focusing on this development as critical to understanding the impact. Five different mental health services in the southern part of Sweden have recently employed peer support workers who then received training provided by an external consultant who focused on recovery principles and introduced the peer support role.

The aim of the study presented here was to investigate the service users’ experience of having contact with peer support workers in Swedish mental health care.

Materials and Methods

Swedish mental health services include both specialized psychiatric treatment services administered by the County medical councils and social support services, including those for community-based mental health needs, administered by the municipalities. It should be noted that the mental health services in this study were provided by the County-based medical psychiatric system. It was particularly significant that these services, focused primarily on psychiatric treatment and working from an expert medical paradigm, were willing to hire these workers and participate in the study.

During the study, one of the seven originally employed workers resigned, which left six offering support to the clients interviewed in this study. The peer support workers were assigned and developed a variety of roles, depending on the nature of the services they were working in. They might meet with individuals to offer support, sometimes ran recovery group sessions together with other staff, acted as support for clients in meetings with the authorities, helped connect clients to service user organizations or assisted clients with finding meaningful daily activities. The peer support workers, regular staff and the managers at the services that had a peer support worker employed were also interviewed. However, only the interviews with the service users will be presented here. The research was approved by a regional ethical vetting board at Lund University, Reg. No.2015/208.

Informants

The inclusion criteria for participation included the presence of mental health issues necessitating ongoing contact with psychiatric services. Exclusion criteria included primary substance abuse, people who had dementia or developmental disorders and people who did not speak Swedish. Eighteen service users were asked to participate and all gave their consent. The informants’ ages varied from 24 to 64 years, with a mean age of 45 years. Most were women (72%) and diagnoses varied between bipolar disorder, depression and psychosis. The informants included in the study had received support from a peer support worker for a period of at least 1 month and up to 2 years.

Procedure

The informants were selected from a psychiatric outpatient service that had employed a peer support worker. In selecting informants there was an attempt to include a variation in age, sex and time spent with the worker. The number of contacts was difficult to document and report, data that might be prioritized in future research in order to study effects relative to exposure and types of services experienced. Initial contact was made with a staff member at each unit who gave written and oral information to eligible service users who fit the criteria. The informants were assured confidentiality and informed of their right to discontinue the interview at any time. The interviews were conducted at the psychiatric unit which the informants attended.

Data Collection

A qualitative approach was employed [16] and the interviews proceeded from semi-structured questions targeting experiences of receiving support from a peer support worker. The questions consisted of themes considered relevant in order to understand different aspects of peer support, for example those related to personal recovery. The interviews took the form of a dialogue, started with broader questions about the informants’ current situation and connection to psychiatric care, and then proceeded to explore the relationship with the peer support worker and the informants’ experience of this support.

Data Analysis

The results were analyzed using content analysis according to Graneheim och Lundman [17]. The transcribed interviews were analyzed by the two authors, one who had gathered the data and managed the project and another that was part of the overall project focusing on the development of peer support services in Sweden.The interviews were read several times by both authors to get a sense of the whole. Further readings then focused on finding meaning units relevant to the research question in the text. The meaning units were then labelled with a code, with themed codes sorted into new categories which consisted of a number of subcategories. Finally, the categories and subcategories resulted in a main theme representing the underlying latent meaning of the data [17].

Results

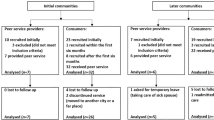

In order to present the results, and attempt to understand them within a model that can capture the characteristics and effects of this example of peer support workers in an outpatient clinic, the following three-tiered structure is used (see Table 1). The primary overarching theme is followed by three summarizing categories that are supplemented with sub-categories explaining and expanding the nature of the results at each level. The three primary categories are further defined by differentiating three levels of focus regarding the effects of peer support from the patient perspective. These effects, as described by the respondents, suggest a focus on the individual level (effects related to the immediate relationship and needs of the respondent), the organizational level (effects which relate to the program or caring environment in which the individual meets the peer support worker), and finally the community level (effects which focus on the individual’s reflections over their future life options in the community). The respondents who have been quoted as representative voices in the categories presented are identified here by the fictive name assigned. The peer support workers are not identified, since there were so few in that area and it would therefore be impossible for them to remain anonymous.

Experience-Based Knowledge, Competence and Non-judgmental Awareness

This was the level of interaction that emerged as the most discussed among the respondents. They described the peer support workers as non-judgmental, as demonstrating a special understanding of their situation and as fellow human beings.

Lived Experience and Understanding

The respondents described the relationship between the experience-based knowledge of the peer support worker and their experience of being understood and accepted in a non-judgmental manner that was a direct result of this knowledge and meeting.

And I feel that it’s really ok in some way, so that… when you meet people who are in the same situation, it feels more like it’s really ok and I can like, be as I am. (Karin)

The respondents describe at least two aspects of the meeting, the first of acceptance based on meeting someone in the same situation and then the feeling of being understood.

Finally, there is someone who comes here who understands, and you can maybe skip having to explain so much. With the peer worker, it’s ok with just a few words and they know what you’re talking about. (Yvonne)

The peer worker also seemed to have a calming effect and an ability to put a dimension of normality in service users’ experiences of mental illness.

When I was feeling really abnormal and ill, and just then I thought, why am I feeling like this and then when you have talked with them (peer workers) they’ve.. what’s it called… taken away the drama in the whole thing… and can say that it’s normal to feel this way, and not to be afraid of it… (Emma)

The respondents clearly describe what might be described as a normalization of an otherwise distancing and isolated experience, at the very least reducing what might be seen as a dramatic amplification of the illness experience itself.

Respect, Security and Mutuality

The respondents identified respect, feeling secure, mutuality, dialogue and a feeling of not being alone in this situation as essential elements of their meeting with the peer workers.

I feel comfortable with him/her, since I know that the peer worker… has a lot of experience of mental ill health…. The peer worker creates a kind of security. (Lisa)

The respondents often compared the peer support workers to the regular staff as a means of answering questions related to their experience of the peer support workers. Even when positively describing the regular professional staff, it became clear that there was a feeling of mutuality often expressed in the nature of the dialogue that they could have with the peer support workers, which differed significantly from discussions with professional staff.

We talk here about the illness itself, but with the peer worker it’s more like a discussion, where we have an exchange, while with the psychologist it’s more like, (they say) this is how it is and how it works clinically… like theoretically. (Sofia)

The respondents described their discussions with the peer worker as more of an exchange between equals and with less of the feeling of being objectified by experts who prescribe, based on diagnosis and symptom management.

And it’s really nice with the peer worker when you come here you don’t feel told off or like a statistic that should just do something, instead that you really can sit down and talk with someone who… who has the diagnosis themselves, and in a really equal, nice way. (Emma)

Inspiration and Hopefulness

The respondents also described finding meaning, inspiration and hopefulness as effects of contact with the peer workers. The peer support worker could share experiences that confirmed and supported the user’s feelings but even strategies for working through practical challenges resulting from the illness, and the experience of moving forward in treatment and hoping for something beyond the illness.

Having a peer worker is also very much to have an inspirer and someone who can show the way a bit, someone who can help you feel you want to talk. And someone who can take your hand a bit when you can’t take care of everything yourself. (Rebecka)

The comments suggest that the stories of recovery do not simply inspire but have the quality of “showing the way”, which offers a concreteness to the recovery process that may be difficult to demonstrate in other ways.

That there’s hope… It’s a little bit just that, to get yourself out… to be free from the anxiety and worry…. I’ve felt that hope was gone for me, that her was no way to get better…. But with the stories form the peer worker I can see that there can be a way to come back. (Holger)

Peer Support Effects the Relationship with the Caring Environment

Respondents describe their impression of the environment in the clinic as being impacted by their experiences related to peer support workers being employed in the organization. They note environmental implications, including being impressed with new thinking on the unit, a feeling of understanding that is attributed to the organization, not just specific actors. They see effects on the staff and are aware of and find it meaningful that the peer workers are accepted by other staff and can be part of the team.

Trust and Willingness to Engage

Many of the respondents described their experience of the peer support workers as part of their relationship with the psychiatry clinic, and even with psychiatry as a system. Their meeting with the peer workers impacted their relationship to the clinic in a number of ways; describing increased trust in a program that was willing to employ individuals with their own experience, and through the increased trust and feeling of comfort, an increased willingness to engage in services that they now felt more clearly reflected their experience and goals.

And I have kind of felt that I have never really felt understood within psychiatry or within medical care either before. Really, not before I was here, it was like a relief to come here, really./… and when I met the peer worker the first time it felt really good and really right, since I’d never before met people with the same experience as I had either. (Karin)

The respondents suggest both general and specific effects, where staff are also seen as being influenced by the presence of the peer worker.

The peer workers openness about their recovery process and sometimes their illness makes it possible for all of us to open up in the discussion group. And I notice that even some of the other staff open up and share some parts of their life experience… So, I think that the peer workers experience and that they are peer workers, and that they are there, makes for a more open climate. (Rebecka)

The informants also describe the presence of peer support workers as part of the professional staff as mediating previous experiences of mistrust towards “the authorities”.

Just this with the peer workers… otherwise I am worried about what I say, I still have a feeling that it can be turned against me, since I’ve experienced that so many times with “regular” psychiatry… This is the first place I can be myself. (Lotta)

Peer Worker as a Link That Builds Equality

The informants also speak quite often of more equality in the environment. Peer support workers, seen as existing in a position “between” the more powerful staff and the patients, are described as bridges between, thereby reducing the power differentials and creating a more equal environment, as people with lived experience are respected as team members within the clinic.

The peer worker is like between us and the staff… the peer worker isn’t completely a staff member, and not completely a patient. It seems clear that the peer worker can go between us and the staff. (Lisa)

The change in the relationship to the staff, as mediated by the peer worker, also seems to affect the individual’s own experience of their illness and self-esteem.

You think you’re like down at the bottom../hopelessly down on the ground,../…. That I can’t feel like an adult, that I’m seen as less knowing, as the sick one…/that you don’t feel worth as much. But it isn’t like that here (with the peer worker) you’re like all the others, it’s like equal. (Monika)

Awakening Hope for a Life Beyond the Illness

This level is explained by references to the hopefulness produced by the peer workers themselves, as confirmation of the possibility for a contributing life in the community. Reduced stigma, especially internalized stigma, is also described as the realization that people with lived experience can recover and be employed to help others, and as reducing the shame and hopelessness they feel in relation to family members and the outside world.

Role Models for Recovery

While the type of hopefulness inspired by the peer workers is often described as an individual recovery-related outcome, we want to emphasize the concrete validation expressed by our respondents of actually meeting someone who has established themselves as participating community member, as well as an employee in a psychiatric context. This became increasingly clear to us as they were not just describing a relationship-based hopefulness, one tied to the immediate short-term inspiration provided in the meeting with the worker, but their experience of the worker’s life as evidence of the possibility of “living beyond” [18] the illness, an extremely vivid confirmation of a real possibility for the future.

The peer worker is sitting there as living proof that it can happen, that you can get out of this. And it’s more physical, more concrete. Anyone can say that, that everything will be alright, but it’s only words. Then you see this reinforced in reality. (Ove)

Reducing Self-stigma

The feeling of reduced stigma goes beyond the individual level and is described as including a new perspective on the patients as a group, a group identity which the individual is dealing with feelings of being a member of.

Like our whole life is made up of some sort of prejudice, as far as we know, what do I know about you, what do you really know about me, what do I know about him (peer worker). He/she is symbolically like a representative for the whole patient group. (Olle)

They even described the ability of the peer support workers to contribute to a hopefulness towards a future life in the community. This may be seen as reducing the self-stigma that may develop in relation to a hopelessness of returning to a participatory life.

The peer worker explained and then we exchanged experiences a bit and the peer worker told me and began to explain that there’s like a life and that you’re not doomed to lie in psychiatry the rest of your life,/I also think that I’ve gotten a whole other view after I got sick and then came here…some support and a little bit that you can see your way forward… that you can work and have a normal life (Sofia)

The comments point to the fact that contact with the peer worker allowed the individual to see themselves as a community member in the future. This effect is even further developed as influencing and supporting the users to begin to consider relationships in the future.

That you feel you are a part of the community, that you don’t feel a hopeless outsiderness and loneliness, instead you feel that you are… a part of the community…it’s been difficult to tell others, my nearest family and friends and I know that I have this depression… There’s all this taboo around it and that makes you yourself scared that someone will see you are sick and what that will mean for how they treat you. We talk a lot about this kind of thing. (Monika)

A Meeting with Broad Recovery-Oriented Implications

The overarching theme which emerged in the analysis built on the varied perspectives on the meaning and experience of peer support contact, in that the effects were not limited to the actual meetings, but suggested much broader gains, related to the individual’s relationship to the caring system and to the broader community. The resulting theme suggests a cumulative effect, one in which the care-giving culture, as impacted by the addition of peer support, becomes a mediating factor in relation to the individual’s experience of mental health services as contributing to a recovery vision for the future. This is an especially significant result given the perception of Swedish psychiatry as narrowly focused on treatment and adherence, especially in the stressed situation the majority of these services find themselves today with regard to time and resources.

A “tipping point” is the point at which a series of small changes becomes significant enough to cause a larger, more important change. The following illustration (Fig. 1) attempts to capture this theme.

Discussion

While each informant gave their own unique story of their journey and struggles towards recovery with reference to the experience of receiving help from a peer support worker, the informants’ experience of receiving peer support were overwhelmingly positive. Some of the respondents however thought there was a need for more peer workers, some described personal chemistry as an important factor which could affect the meetings and they were sometimes not aware of what the peer worker could offer and what type of support they might expect.

In comparison to other staff on the unit, the service users stated that they could describe problems more openly, talk about subjects they would not discuss with other staff and that they did not feel a pressure to meet the expectations of the staff in the same way. They saw the peer support worker as a role model that gave them hope and a feeling that they could also feel better and recover. The empowering effects of interacting with role models who have recovered from mental illness, seen in the results here, is often described as a powerful tool in reducing self-stigma [19]. Feelings of loneliness and of being an outsider (alienation) were reduced through the support from the peer worker as well and the service users described being ready to invest more in their treatment. Many of these findings concur with earlier research of service users experience of receiving peer support [5]. The results related to the caring environment presented here however suggest a need for developing further knowledge regarding how implementing peer support services can impact and even transform the culture in which patients meet with and engage in psychiatric services.

The recovery paradigm, which has become an increasingly central focus in many western countries, directing systems to work towards a vision of recovery for all, is an emerging focus in Sweden as well. While a medical paradigm still dominates much of traditional mental health care, a focus on recovery-focused practice is now developing together with an increased emphasis on user involvement in psychiatric care [20]. In describing the components of a recovery-oriented practice or system, a system of services that can contribute to and support the individual’s own possibilities for recovery, LeBoutillier et al. [21] stress; working relationships with professionals built on partnership and hope, a holistic, strengths-based focus that can help the individual to develop their own recovery goals, organisational commitment (to creating structures and environments that support recovery) and the promotion of citizenship, social integration and participation. The concept of a recovery-oriented system includes therefore the quality of the individual relationships between users and program staff, the caring environment itself as a contributing factor and the overall focus on hopefulness for and possibilities of becoming a participatory member of the community. Much of the research on peer support workers has focused however, on the quality of relationships and individual recovery-oriented goals while organisational commitment and promoting citizenship has been less in focus. This may in part be due to the fact that demands for evidence, prior to investing in developing peer support as members of the mental health work force, often focus primarily on immediate and individual illness-related individual effects.

It becomes clear however, that many of the results presented here can be interpreted as specific examples of the caring organisation itself taking a step forward in achieving a recovery-orientation, a result which has also been reported in other research [22]. When service users express that the peer support workers help them to trust the clinic, and are therefore more willing to engage in services, they may be seen as suggesting that the peer support workers confirm the organisational commitment to a recovery philosophy in the unit, and that the actual hiring is in many ways powerful and concrete evidence for the user that they really believe in recovery.

Conclusion

While the results of this study confirm and add to the growing literature regarding the positive experiences of having contact with peer support workers, additional themes that emerged in the analysis point to organizational and environmental effects that may be analyzed in relation to recovery and recovery-oriented systems. The results suggest, as reflected in the primary theme, that the effects were not limited to the actual meeting, but describe the potential for much broader gains, that might impact the individual´s relation to the caring system and to the broader community.

The results of this study, when considered within the frame of an organizational perspective described within the literature on recovery-oriented systems, would point to the addition of peer support workers as potentially decisive in contributing to a more recovery-oriented service. While the professional staff and the essential services they offer are of course necessary for recovery, and the respondents often express appreciation for the services they receive, the results suggest that the overall trust in and willingness to engage with psychiatry may improve with the addition of peer support workers. This is an especially important result for systems such as that in Sweden, where medical psychiatry is organizationally separate form community-based social services, and where recovery oriented relationships between users and providers are often lacking. In addition to creating trust and engagement, the peer support workers seem to contribute a vision and validation of a hopefulness for recovery in the future, a vision which the study suggests may also positively impact the way in which they value the traditional, clinical services they receive, which may now be seen in relation to the possibility of feeling better and gaining access to a life in the community. This point is also particularly important for services where clinicians do not routinely have contact with users who have recovered, and the peer support workers therefore offer both staff and patients a unique perspective.

The study suggests that the addition of peer support workers may be a small, but significant change in the staffing and organization, one which may have wide-ranging effects in supporting a recovery orientation that includes hopefulness for a future life in the community, a finding that future research studies will need to investigate.

Limitations

This was a small, pilot study and our selection of service users may have been dominated by those who met with the peer support worker due to a positive expectation regarding their interaction. We know there were some users who did not have contact with the peer support worker and others who perceived the worker as stressed and without a clear structure, which meant that they avoided seeking contact with them. Issues regarding roles, interaction with the professionals, attendance at team meetings, and specific services that might be offered to the service users point to a number of implementation issues, which are not fully addressed here, and which will be important to focus on in future studies.

References

Gillard S, Foster R, Gibson S, Goldsmith L, Marks J, White S. Describing a principles-based approach to developing and evaluating peer worker roles as peer support moves into mainstream mental health services. Mental Health Soc Incl. 2017;21(3):133–43.

Slade M, Amering M, Farkas M, Hamilton B, O’Hagan M, Panther G, Perkins R, Shepherd G, Tse S, Whitley R. Uses and abuses of recovery: implementing recovery-oriented practices in mental health systems. World Psychiatry. 2014;13:12–20.

Lloyd-Evans B, Mayo-Wilson E, Harrison B, et al. A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials of peer support for people with severe mental illness. BMC Psychiatry. 2014;14:39.

Repper J, Carter T. A review of the literature on peer support in mental health services. J Mental Health. 2011;20(4):392–411.

Walker G, Bryant W. Peer support in adult mental health services: a metasynthesis of qualitative findings. Psychiatr Rehab J. 2013;36(1):28–34.

Sells DL, Davidson L, Jewell C, Falzer P, Rowe M. The treatment relationship in peer-based and regular case management for clients with severe mental illness. Psychiatr Serv. 2006;57(8):1179–84.

Rogers S, Maru M. A randomized trial of individual peer support for adults with psychiatric disabilities undergoing civil commitment. Psychiatr Rehabil J. 2016;39(3):248–55.

Salzer M, Rogers J, Salandra N, et al. Effectiveness of peer-delivered center for independent living supports for individuals with psychiatric disabilities: a randomized controlled trial. Psychiatr Rehabil J. 2016;39(3):239–47.

Rooney JM, Miles N, Barker T. Patients’ views: peer support worker on inpatient wards. Mental Health Soc Inclusion. 2016;20(3):160–6.

Davidsson L, Bellamy C, Guy K, Miller R. Peer support among persons with severe mental illnesses: a review of evidence and experience. World Psychiatry. 2012;11:123–8.

Ochocka J, Nelson G, Janzen R, Trainor J. A longitudinal study of mental health consumer/survivor initiatives: part 3—a qualitative study of impacts of participation on new members. J Community Psychol. 2006;34(3):273–83.

Mahlke C, Priebe S, Heumann K, Daubmann A, Wegscheider K, Bock T. Effectiveness of one-to-one peer support for patients with severe mental illness—a randomised controlled trial. Eur Psychiatry. 2017;42:103–10.

Sledge W, Lawless M, Sells D, Wieland M, O’Connell M, Davidson L. Effectiveness of peer support in reducing readmissions of persons with multiple psychiatric hospitalizations. Psychiatr Serv. 2011;62(5):541–4.

Crane D, Lepicki T, Knudsen K. Unique and common elements of the role of peer support in the context of traditional mental health services. Psychiatr Rehabil J. 2016;39(3):282–8.

Gillard S, Holley J. Peer workers in mental health services: literature overview. Adv Psychiatr Treat. 2014;20(4):286–92.

Kvale S. Doing interviews. Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications; 2008.

Graneheim UH, Lundman B. Qualitative content analysis in nursing research: concepts, procedures and measures to achieve trustworthiness. Nurse Educ Today. 2004;24(2):105–12.

Anthony W. Recovery from mental illness: the guiding vision of the mental health service system in the 1990s. Psychosoc Rehabil J. 1993;16(4):11–23.

Corrigan PW, Watson AC. The paradox of self-stigma and mental illness. Clin Psychol Sci Pract. 2002;9(1):35–53.

Schön U-K, Rosenberg D. Transplanting recovery? Research and practice in the Nordic countries. J Mental Health. 2013;22(6):563–9.

Le Boutillier C, Leamy M, Bird V, Davidson L, Williams J, Slade M. What does recovery mean in practice? A qualitative analysis of international recovery-oriented practice guidance. Psychiatr Serv. 2011;62(12):1470–6.

Gray M, Davies K, Butcher L. Finding the right connections: peer support within a community-based mental health service. Int J Soc Welf. 2017;26:188–96.

Funding

The study was funded by Department of Psychiatry—Region Skåne.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Rosenberg, D., Argentzell, E. Service Users Experience of Peer Support in Swedish Mental Health Care: A “Tipping Point” in the Care-Giving Culture?. J. Psychosoc. Rehabil. Ment. Health 5, 53–61 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40737-018-0109-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40737-018-0109-1