Abstract

Decisions are often postponed even when future profits are not expected to compensate for the losses. This is especially relevant for financial and entrepreneurial disinvestment choices, as investors often have a disposition to hold on to losing assets for too long. We use an experiment with real real-options to study one possible behavioral motivation. Studies in psychology suggest that individuals have different styles of handling the stress involved in making decisions. We find that participants' styles of decision-making and risk aversion as well as the interaction of those can assist in predicting the likelihood that the participants will make investments and the timing of their disinvestment decisions. We also find the overall structure of the findings to be in line with a planner–doer model.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

When an investment decision that has irreversible consequences can be postponed, it is often advisable to postpone it even when the expected net present value of immediate implementation is positive. If a business is losing, for example, disinvestment has positive net present value, but staying in business might, nevertheless, be rational, taking a real-options perspective (Titman 1985; Brennan and Schwartz 1985; McDonald and Siegel 1986; Dixit 1991; Dixit and Pindyck 1994; Weeds 2002). Disinvestment decisions, however, are often postponed beyond rational considerations, i.e., even when (the extent of) waiting is unlikely to be profitable (for experimental findings, see, e.g., Sandri et al. 2010; Musshoff et al. 2013). It is often argued that behavioral characteristics can explain some of this ‘holding-on-for-too-long tendency’ (Sandri et al. 2010; more generally: Thaler 1981; Akerlof 1991). But what exactly are those behavioral characteristics? This question is at the center of the current contribution.

The psychological motivations for postponement of decisions that economists have, so far, studied most frequently are procrastination and commitment to past decisions (Samuelson and Zeckhauser 1988; Burmeister and Schade 2007; Loewenstein and Prelec 1992; O'Donoghue and Rabin 1999, 2001; Angeletos et al. 2001; Ariely and Wertenbroch 2002; Gul and Pesendorfer 2004; Della Vigna and Malmendier 2004; Sivanathan et al. 2008; Post et al. 2008; Khavul et al. 2009). But those two are hardly of any relevance in the Sandri et al. (2010) setting that our study is building up upon, i.e., for multi-period disinvestment decisions. Procrastination is about the postponement of a certain task, whereas there is no actual task in Sandri et al. or our scenario. Even stretching the idea of a task to making decisions, this ‘task’ cannot be avoided via an avoidance of exit, due to the repetitive nature of the decision. The latter argument also applies to status quo tendencies that should ‘wash out’ over multiple periods. But what other behavioral tendencies could then be relevant, and are there any individual differences with respect to this postponement tendency that help to better understand such behavior?

Interestingly, Ameriks et al. (2007a, b) find, in a somewhat related situation, that individuals use similar decision-making processes when making economic and non-economic decisions.Footnote 1 This finding suggests that using a psychological framework for identifying and studying styles of decision-making can assist in predicting economic outcomes. In this contribution, we take a step in that direction. We use a model developed by psychologists, the conflict theory of decision making (Janis and Mann 1977; Mann et al. 1997), to predict the behavior of participants in an economic lab game. The theory of decision-making assumes that the decisional conflict that precedes a decision engenders psychological stress. The theory further predicts that individuals differ in their styles of handling the stress. To test the predictions of this theory, we use a questionnaire that is based on Mann et al. (1997) to measure individuals' propensities to be vigilant and to buck-pass (for details on these characteristics, see the next section). We also measure the participants risk aversion. Finally, we test the correlation between the interaction of vigilance, buck-passing, and risk-aversion to estimate the number of rounds that participants play in an investment/disinvestment experiment with real monetary-stakes in which postponing decisions is costly.

There is another theory that is relevant for our research. Specifically, we believe that behavior in our setting can be explained in terms of a planner–doer model. Those models are often used to study decision-making processes where agents make decisions that are inconsistent with payoff maximization. They are used, for example, to study savings decisions, the consumption of hedonic goods, the employment of commitment devices and of addiction (Thaler and Shefrin 1981; Frederic et al. 2002; Gul and Passendorfer 2004; Prelec and Bodner 2005; Fudenberg and Levine 2006).Footnote 2

Planner–doer models suggest that decision-making processes involve a long-term self, a planner, and many doers. Each doer exists for one period and is then replaced by another. The planner makes long-term plans and gains utility from the benefits accumulated over all periods. The doers, however, make the decisions, with each doer making decisions in the one period in which she exists, and her utility is affected only by the instantaneous costs and benefits. When the planner draws a strategy, therefore, she must take into account that the doers might implement decisions that differ from the ones she finds optimal. Because of this, as explicated in the next section, interactions between risk propensity and vigilance/buck-passing might become relevant in both investment and disinvestment decisions.

We get results that are largely consistent with our expectations, as will be shown and discussed throughout the paper. The rest of the paper is organized as follows. In Sect. 2, we introduce the conflict theory of decision-making and the two concepts which we are measuring, vigilance and buck-passing. We also relate these concepts to a planner–doer model. In Sect. 3, we describe the methodology and the data. In Sect. 4, we present the results. In Sect. 5, we briefly discuss our findings. We conclude in Sect. 6.

2 Buck-passing and vigilance according to the conflict theory of decision-making and in connection to a planner–doer model

As said, a central approach which we are building upon is Janis and Mann’s (1977) conflict theory of decision making, which we apply to predict individuals' choices in an experimental setting. Quite generally, the theory supposes that individuals differ in their styles of handling the stress of making a decision (Loewenstein and Lerner 2003). Clearly, researchers working in the field of stress responses have rapidly accepted it as an interesting contribution (see Lazarus and Folkman 1984). It has inspired research into decision-making under threat-engendered stress (Keinan 1987). It has also inspired new decisional architectures in complex situations such as air traffic control (O’Hare 1992). Some studies have emphasized the role of stress in this model as a driver of distorting information and of triggering pre-programmed responses (Folger et al. 1997). Moreover, the Janis and Mann scale has been adapted in a slightly different context by Heredia et al. (2004).

Of the number of factors that Mann et al. (1977) discuss, we concentrate on vigilance and buck-passing because of their special relevance for our disinvestment scenario. We first describe the characteristics of vigilance as a general driver of behavior and then continue with buck-passing, followed by some general considerations on the relationship between the conflict theory of decision-making and the planner–doer model. Vigilance is an established concept in psychology, originating from human–machine interaction and first analyzed in World War II to better understand people’s continuous attention (and the breakdown of this ability) with visual cues, especially radar detection (Mackworth 1948). With respect to decision-making, more generally, individuals that are vigilant have the ability to handle the stress of decision-making well: they process all the available information and make decisions rationally (Janis and Mann 1977). Vigilant individuals, therefore, make decisions as soon as they receive information suggesting that a decision has to be taken.

Other individuals, however, have maladaptive styles of handling the stress. One of the most important maladaptive styles is buck-passing. Originating from political strategy (i.e., countries waiting for other countries to confront an aggressor), buck-passers find decision-making stressful and, consequently, they prefer to delegate decisions to others. Loneck and Kola (1989), for example, find that buck-passer alcoholics, for example, find it harder to choose among a set of alternatives. Fioretti (2009) find that buck-passers try to delegate tasks to others, and that, consequently, tasks are not handled over a long period. Thus, buck-passers do not only buck-pass tasks to others; when they cannot pass the buck to someone else, they delegate it to a future period. Indeed, according to Mann et al. (1997), a buck-passer is one, who, among other things, identifies with the statement: “I do not make decisions unless I really have to”.Footnote 3

One method to identify individuals' styles of decision-making is Mann et al.’s (1997) questionnaire-based test. This questionnaire has been used in a large number of papers, and it was found that the results are correlated with self-esteem, health, and more, in a way consistent with the prediction of Janis and Mann (1977). Gorodetzky et al. (2011), for example, use the Mann et al. (1997) questionnaire and report that stimulant use is correlated with maladaptive decision-making styles. Phillips and Reddie (2007) report that procrastination, as measured by the Mann et al. (1997) scale, is correlated with inefficient email use in the workplace. Mann et al. (1998) tested the Mann et al.’s (1997) questionnaire with participants from both Western and Eastern societies, and report that the results support the hypothesis that the conflict model of decision-making is relevant to participants from both societies (see also: Engin 2006; Sirois 2007; Brown and Ng 2012). We use the relevant parts of Mann et al.’s (1997) questionnaire to get participants’ scores of vigilance and buck-passing.

Both vigilance and buck-passing are behavioral tendencies of both doers and planners. Planners have the same decision making style as the doers. Planners have to take into account the doers’ styles of decision making. Vigilant doers are not problematic from a planner’s perspective, especially when they are also risk averse, because risk averse vigilant doers make careful decisions. Buck-passing doers, on the other hand, especially those that are risk-taking, should evoke anticipatory actions by the planners, because they are likely to avoid making decisions, resulting in holding on too long. More details are provided in the predictions section.

3 Methodology and data

3.1 Experimental framework

To test participants' propensities to delay decisions, we use an experiment that is based on the framework employed by Sandri et al. (2010). The Sandri et al.’s (2010) experiment is intended to test the predictions of real-options theory versus a general waiting tendency (called ‘psychological inertia,’ not further specified in their paper) with disinvestment decisions. It mimics the decisions of an entrepreneur that has to choose between disinvesting and keeping her business running.

In the experiment, a participant faces a series of stages; in each stage, she can choose between winning an uncertain prize and playing on in the next stage, or disinvesting and earning a certain prize. The theory of real-options suggests that participants should disinvest as soon as the prize for disinvestment is larger than the expected prize from playing on.

Sandri et al. (2010) find that participants respond to incentives when making disinvestment decisions, but, at the same time, they usually play on even when disinvestment is expected to be more profitable. Below, we extend the Sandri et al.’s (2010) framework in three ways.

First, we add an investment stage in which the participants have to decide whether to invest or to skip the game. This stage is intended to mimic the first step in a real-life investment decision: Entrepreneurs do not face a choice between continuing to keep their business running and disinvesting before they consider the possibilities and decide to invest. Second, whereas in Sandri et al. (2010), the participants played a number of games, in each of which they could earn identical prizes; in our settings, the possible prizes change between rounds. Thus, our experiment tests the robustness of the Sandri et al.’s (2010) results to changes in the prizes and in the variance of the prizes. Third, we add a questionnaire that tests the participants' vigilance and buck-passing scores. This allows us to test the correlation between the participants' scores and their decisions in the game.

3.2 Details of the experiment

3.2.1 Implementation

The experiment was fully computerized and conducted in a computer lab of a major German university.Footnote 4 We conducted seven sessions. The number of participants in each session varied between 7 and 14. The total number of participants was 85. The participants were students and non-students that were recruited via the university's website. All the sessions were conducted within 1 week.

In our baseline treatment, the compound-interest treatment, the settings were as follows. Each participant first read the instructions and then answered questions that tested her understanding. After a participant answered all the questions correctly, she played one practice game. The practice game was followed by six experiment games.

3.2.2 Basic game structure

All the games had an identical structure. We begin by describing the settings in one of the six games in some detail, followed by a description of the differences with the other five:

-

The first stage of the game was an investment stage. In the investment stage, each participant learned the following: (a) that she receives 18,000 points as an initial endowment, and (b) that at the end of the experiment, she will receive one Euro for every 6000 points she earns.Footnote 5

-

Second, each participant learned that she can invest 10,000 points. If a participant did not invest, she received a total of 36,531 points. This sum was composed of 10% interest on the 10,000 points that were not invested by the participant, compounded over 11 rounds, plus the original 18,000 points.

-

Third, each participant learned that if she invests, she will start a game that lasts up to 11 rounds.

-

Fourth, she learned that each of the 11 rounds has an identical structure. Each round started with information about the round prize and the possible prizes in the following rounds. The round prize was the prize that a participant won with certainty if she played on. The prizes in the following rounds were either larger or smaller than the prize in the current round: With a 50% chance, the round prizes increased by 200 points between consecutive rounds and with a 50% chance, the prizes decreased by 200 points.

To simplify the presentation of the possible round prizes and the probability of earning each prize, in each round, the participants were presented with a figure depicting the possible prizes in each round left to play and the probability of earning each prize.

For example, Figs. 1 and 2 depict the information presented to a participant in rounds 1 and 2, respectively. The information presented in Fig. 1 shows that if the participant chose to play on, she earned the first-round prize of 1000 points with certainty. The prize in the second round was either 800 or 1200 points, each with 50% probability. The probabilities of the possible prizes in all the other rounds are also depicted in the figure.

Figure 2 depicts the information revealed to the same participant after she chose to play on. The figure shows that the second-round prize was revealed to be 1200 points. The probability of winning each of the prizes in rounds 3, 4…11 was updated accordingly: for example, the probability of earning each of the prizes of 1400 and 1000 points in the third round changed to 50%. The prize of 600 points, on the other hand, is no longer shown, because the probability of earning it became zero.

In addition to information about the possible prizes, each participant was also given the following information. First, each participant was given information about the sum of the prizes which she already earned. This was composed of all the round prizes which she earned in the previous rounds, plus 10% interest on these sums, accumulated over all the rounds since earning them and until the 11th round.

Second, each participant was presented with information on the payoff she will receive if she disinvests rather than plays on. This payoff was composed of a disinvestment-prize of 11,000 together with all the sums earned up to the current round plus 10% interest on the disinvestment-prize, accumulated over all the rounds left until the 11th round.

Finally, the participants learned that if they play on until the 11th round, then after they make their decision in that round, the game will end. In that case, they will earn all the sums which they accumulated up to that round plus the disinvestment-prize, but they will earn no interest on the disinvestment-prize.

Figure 3 depicts an example of the information presented to a participant in each of the rounds which she played. In the investment stage, the participant received information about the investment-cost, the disinvestment-prize, the first-round-prize and about the change in the prizes between consecutive rounds. The participant chose to invest.

In the first round, the participant learned that the prize she will earn (including interest) if she disinvests is 31,384 points. She also learned that if she plays on, she will earn 1000 points and then move to the second round. In the second round, she again learned about the prizes which she already won, about the disinvestment prize, she will earn if she disinvests, and that she will earn 800 points if she plays on. The disinvestment-prize, including interest, was smaller in this round (28,531 points) than in the first round, because by playing on in the first round, the participant lost one round of interest on the disinvestment-prize.

In the third round, the participant learned that if she plays on she will earn 600 points. At this stage, the participant decided to disinvest. She then learned that she earned a total of 38,415 points (this sum includes the difference between the initial endowment and the investment-cost).

3.2.3 Other games/treatments

We refer to a game with the parameters given above as low-variance-low-first-prize game. In low-variance-low-first-prize games, the investment-cost was 10,000 points, the first prize was 1000 points, disinvestment-prize was 11,000 points, and the difference between the prizes in consecutive rounds, to which we refer as variance, was 200 points.

Because we wanted to test the robustness of our results to size effects, we let each participant play five more games. The games differed in their investment-costs, disinvestment-prizes, first-round-prizes, and variances. In low-variance-high-first-prize games, the investment-cost was 10,000 points, the first-round-prize was 1500 points, the variance was 200 points, and the disinvestment-prize was 11,000 points. In high-variance-low-first-prize games, the investment-cost was 15,000 points, the first-round-prize was 1000 points, the variance was 1000 points, and the disinvestment-prize was 16,000 points. In high-variance-high-first-prize games, the investment-cost was 15,000 points, the first-round-prize was 1500 points, the variance was 1000 points, and the disinvestment-prize was 16,000 points.

In addition, each participant played one extra-profit game and one losing game. There were two types of extra-profit games and two types of losing games. In extra-profit-low-variance games, the investment-cost was 10,000 points, the first-round-prize was 1000 points, the variance was 200 points, and the disinvestment-prize was 16,000 points. In extra-profit-high-variance games, the investment-cost was 10,000 points, the first-round-prize was 1000 points, the variance was 1000 points, and the disinvestment-prize was 16,000 points.

In losing-low-variance games, the investment-cost was 15,000 points, the first-round-prize was 1000 points, the variance was 200 points, and the disinvestment-prize was 11,000 points. In losing-high-variance games, the investment-cost was 15,000 points, the first-round-prize was 1000 points, the variance was 1000 points, and the disinvestment-prize was 11,000 points.

With these parameters, the optimal strategy in a losing game for a risk-neutral (and risk-averse) participant was not to invest. For all but participants with extreme values of risk aversion, it was optimal to invest in the extra-profit games. Thus, the losing games tested whether participants will avoid playing games with negative expected profits. The extra-profits games were for inducing very risk-averse participants to play at least one game.

About one quarter of the participants played an extra-profit-low-variance game together with a losing-low-variance game, about one quarter played an extra-profit-low-variance game together with a losing-high-variance game, about one quarter played an extra-profit-high-variance game together with a losing-low-variance game and the rest played an extra-profit-high-variance game together with a losing-high-variance game. For all the participants, the losing games were always the fifth games. The order of the other games was random.

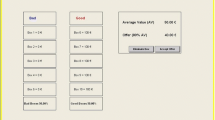

Table 1 summarizes the parameters of the various games. The table also gives the trigger-prizes, the expected number of rounds, and the expected payoffs. The trigger-prizes are the smallest prizes that make a participant indifferent between playing on and disinvesting. We find their values by a backwards induction process that assumes that participants disinvest as soon as the expected payoffs from playing on become smaller than the disinvestment-prize.

3.2.4 Expected exit period

The expected number of rounds is calculated in two steps. In the first step, we find for each round i the probability that this will be the first round in which the round-prize will drop below the trigger-prize, pi. In the second step, we calculate the expected number of rounds, E(X), as E(X) = Σi×pi. The expected payoffs are calculated by multiplying each payoff by the probability of earning it, conditional on the participant not disinvesting earlier, and summing the results.

All these parameters are calculated, assuming that participants play as predicted by the theory of real options. Consequently, these parameters are calculated under the assumption that the participants are risk-neutral. Musshoff et al. (2013) show that in our settings, risk-averse participants are expected to disinvest at earlier stages than risk-neutral participants. The results which we derive below are therefore conservative estimates of the differences between the participants' disinvestment times and the disinvestment times implied by normative theory.

As a robustness check, we also had a decreasing-interest treatment to check the robustness of the results to framing effects. The settings in the decreasing-interest treatment are identical to those in the compound-interest treatment, except that in the decreasing-interest treatment, the participants were informed that the disinvestment-prize will decrease by 10% for each round which they choose to play.

The disinvestment-prize in the first round, however, was the same as the disinvestment-prize including interest in the first round of the compound-interest treatment. Thus, the compound-interest and the decreasing-interest treatments were normatively identical, but in the compound-interest treatment, the framing was of interest gains, whereas in the decreasing-interest treatment, the framing was of interest losses.

3.2.5 Measuring individual differences

After all the participants finished playing the six games, each participant completed a Holt and Laury (2002) test for risk aversion. The Holt and Laury (2002) is used in a plethora of economic experiments and uses a so-called ‘price-list’ schema. Respondents face, subsequently, several options to choose between a less risky and a riskier lottery. The respondents are first confronted with a choice where the high-risk option is quite unattractive and move, from stage to stage, to choices where the price of avoiding the risk becomes higher and higher.

The participants also completed a short questionnaire on their demographics and a test of their patterns of decision-making. The decision-making test was a German translation of the Mann et al.'s (1997) vigilance and the buck-passing scales.

Each of the two scales is composed of six statements such as “I try to find the disadvantages of all the alternatives” (vigilance scale) and “I do not make decisions unless I really have to” (buck-passing scale). For each of the 12 statements, each participant indicated how much she agrees or disagrees with the statement on a five-point scale that went from fully agree (2) to fully disagree (− 2).

We find that the Cronbach alphas of both the buck-passing and the vigilance items are satisfactory and similar to those reported in Mann et al. (1997). The Cronbach alpha for the vigilance scale in our sample is 0.85, compared to 0.80 in Mann et al. (1997). The Cronbach alpha for the buck-passing scale in our sample is 0.82, compared to 0.87 in Mann et al. (1997). We also find, as predicted, that the two scales are negatively correlated (r = − 0.17, p < 0.01).

We use the average of each participant's responses on the six buck-passing items as the participant's buck-passing score. We use the average of each participant's responses on the six vigilance items as the participant's vigilance score.

After all the participants filled the buck-passing and vigilance tests, the computer picked one game at random and the participants were paid according to their payoffs in the selected game. The participants were also informed about their payoffs in the Holt and Laury (2002) test. Thus, the participants learned their payoffs only after they completed all the stages of the experiment. The experiment took about 45 min. The average payoff, including show-up fees, was 12.49 Euros with a maximum of 19.75 Euros.

Table 2 reports the participants' summary statistics. The average age of the participants was 27.8. About 76% of them were students. Out of the students, about 14% study economics or business. The average vigilance score is 0.79 and the average buck-passing score is − 0.59. We define a participant's CRRA score as the CRRA coefficient that satisfies the participant's pattern of choices in the Holt and Laury (2002) test.Footnote 6 A negative score, therefore, indicates that a participant is risk-loving, zero indicates that she is risk-neutral, and a positive score indicates that the participant is risk-averse. The average CRRA score is 0.86, suggesting that most participants in our sample are risk-averse in the payoffs at stake.

4 Predictions

Real options theory suggests that participants should disinvest as soon as the expected value of the future prizes drops below a certain threshold level (trigger-prize). Furthermore, Musshoff et al. (2013) show that risk-averse individuals should disinvest even earlier. This suggests that the predictions of real-option theory, which are based on an assumption of risk-neutrality, are higher bounds of the preferred timing of disinvestment of most individuals. Yet, the evidence on the tendency to postpone disinvestment decisions suggests that many individuals postpone disinvestment decisions even when staying is expected to lead to significant losses (Shefrin and Statman 1985; Samuelson and Zeckhauser 1988; DeTienne et al. 2008).

We hypothesize that styles of decision-making can be used to explain these findings on an individual level. Participants with high scores of buck-passing tend to hold on to losing assets even when they have information, suggesting that disinvestment is more profitable. Participants with high scores of vigilance, on the other hand, are likely to disinvest as soon as they realize that playing on is costly.

It may also be expected that when decisions are made under uncertainty, risk-averse individuals will prefer less risky payoffs over risky ones and hence, in our decision situation, exit earlier. It was found, however, that in settings similar to ours, risk aversion did not consistently predict early disinvestments. In Sandri et al. (2010), risk aversion did not predict disinvestment decisions, whereas in Musshoff et al. (2013), there was a correlation between risk aversion and the timing of disinvestments.

The conflict theory of decision-making, in conjunction with a planner-doer model, offers a possible explanation for these indecisive results. Doers may be seen as exhibiting bounded rationality and, consequently, doers may not always pay full attention to the information facing them. Rather, doers may pay more attention when the perceived stakes are high and less attention when the perceived stakes are low.

Risk-averse individuals tend to view stakes as high, because they are averse to even small losses. They, therefore, have greater incentives than risk-tolerant individuals to dedicate time and effort to studying the possible outcomes before making a decision. Thus, when individuals face a decision between continuing a status quo and disinvesting, risk-averse individuals are likely to dedicate more effort to processing all the available information. Risk-averse individuals are, therefore, more likely to find out that continuing the status quo is costly than risk-tolerant individuals. However, even if a participant realizes that disinvestment is preferable, disinvesting might be related to the doers’ decision-making style. Specifically, a buck-passing participant might keep on playing even when she knows she had better disinvest. Thus, the joint effect of low-risk aversion with buck-passing might have a strong effect on behavior: such doers both do not pay attention to the data before making decisions, and suffer stress when having to disinvest. Thus, for such doers, nothing ‘stands against’ staying in the game forever. On the other hand, a vigilant participant is likely to disinvest as a rational strategy even if she is not much risk averse, but the joint effect of risk aversion and vigilance should be very strong. Thus, we can expect that the correlation between risk aversion and the timing of disinvestment is a function of the interaction between risk aversion and the buck-passing/vigilance scores.

5 Results

5.1 Probability of skipping a game

In each of the six games that the participants played, the participants first decided whether they invest to play the game or not. Participants that did not invest received the capitalized investment-cost and continued to the next game. Participants that chose to invest paid the investment-cost and started the game.

We use the term skip to refer to the decision not to invest. Columns 1, 3, and 5 in Table 3 provide summary statistics on the likelihood that a game was skipped.

From the table, it seems that the order of the games did not affect the likelihood that participants skipped games. This is corroborated by statistical tests. The ANOVA F-statistics for the order of the games and for the interaction between the order of the games and the type of treatment are both statistically insignificant (F = 0.61, p > 0.10 and F = 0.89, p > 0.10, respectively). We, therefore, do not control for the order of the games in the regressions below.

It also seems from the table that participants were more likely to skip games in the compound-interest treatment. We, therefore, control for the type of treatment in the models we estimate below.

To estimate the probability that a participant skips a game, we estimate both linear probability models (LPM) and probit models. To control for the possibility that decisions made by the same participant are correlated, we cluster the standard errors at the participants’ level cluster the standard errors at the participants' level.

The dependent variable is a dummy that equals 1 if a participant skipped a game and 0 if she invested to play the game. In column 1 (linear probability model) and column 3 (probit model), the only independent variables are the main variables of interest: the buck-passing and vigilance scores, the risk-aversion score based on the Holt and Laury procedure, and the interaction of the buck-passing and vigilance scores with the risk-aversion score. In addition, we also include a dummy that equals 1 if the trial is in the decreasing-interest treatment and 0 if the trial is in a compound-interest treatment. For simplicity, we focus on the results of the LPM model (column 1). The results of the probit model are qualitatively similar. It can be observed that the coefficient of the buck-passing index is positive (\(\beta =0.006, p<0.09\)) and marginally significant. Therefore, participants with high buck-passing scores are more likely to skip. The effect is economically significant. A one-standard-deviation increase in the buck-passing score is associated with an increase of 0.25% in the likelihood of skipping a game. This is a large effect, considering that only about 0.5% of the games were skipped.

The coefficients of the other variables are not statistically significant, but the results suggest that an increase in the risk-aversion scores might be associated with a decrease in the likelihood of skipping games. To further test the results, we add in column 2 (LPM model) and 4 (probit model) further independent variables that control for the attributes of the games and for the participants’ characteristics. These include: the log of the investment-cost which is either 10,000 or 15,000 points, the log of the disinvestment-prize which is either 11,000 or 16,000 points, the log of the variance which is either 200 or 1000 points, the log of the first-prize which is either 1,000 or 1500 points, the maximum and minimum prizes which a participant could win in the game, the participants' age, a man dummy that equals 1 if a participant is a man and 0 if the participant is a woman, a student dummy that equals 1 if a participant is a student and 0 otherwise and a German-born dummy that equals 1 if a participant was born in Germany and 0 otherwise.

We find again that an increase in the buck-passing score is associated with an increase in the likelihood of skipping games (\(\beta =0.007, p<0.05\)). In this specification, we also find that the coefficient of the interaction between the buck-passing score and the risk-aversion score is negative and marginally statistically significant (\(\beta =-0.007, p<0.08\)). The coefficients cancel each other out (\({\chi }^{2}=0.03, p>0.85\)). Thus, it seems that the more risk-averse a buck-passer becomes, the more likely she is not to skip a game. In other words, more risk-aversion makes buck-passing participants more likely to play games. This is in line with our theorizing about the interplay between risk-aversion and buck-passing in the context of a planner-doer model. Planners should be less concerned with a buck-passing doer if she is at least risk-averse.

5.2 Rounds played until disinvesting

Participants that did not skip played a game that lasted until they disinvested, or until the 11th round. real-options theory suggests that participants should disinvest as soon as the round-prizes drop below the trigger-prizes. As discussed above, risk aversion should encourage participants to disinvest even earlier (Musshoff et al. 2013), as risk-averse participants prefer certain payoffs over risky ones. Normative theory predicts, therefore, that participants should play, on average, relatively short games.

We expect, however, that styles of decision-making will affect the timing of disinvestment: Buck-passers would play even when they realize that playing on is costly, while vigilant participants play more efficiently (Janis and Mann 1977; Mann et al. 1997).

We use a Cox proportional hazard model to estimate the probability of disinvestment in each round, conditional on the participant not disinvesting earlier. We use the Cox hazard model, because it is a semi-parametric model. It allows us to estimate the probability of disinvestment without making assumptions about whether the probability of playing on increases or decreases with the number of rounds played.

In the Cox model, the regression coefficients exhibit the conditional effect of a change in a parameter on the probability that a participant will disinvest in a given round, given that the participant did not disinvest earlier. A positive coefficient suggests, therefore, that an increase in the variable increases the probability of disinvestment. To control for the possibility that decisions made by the same participant are correlated, we use random effects and cluster the results at the participants' level.

In column 1, we include in the regression only the buck-passing and vigilance scores, the risk-aversion score, the interaction of the buck-passing and vigilance scores with the risk-aversion score, and a dummy for decreasing-interest treatments. The results are summarized in column 1 of Table 4.

We find that the coefficient of the buck-passing score is negative (\(\beta =-0.200, p<0.05\)), suggesting that an increase in the buck-passing score is correlated with a smaller probability of disinvesting; i.e., the higher the buck-passing score, the higher the probability that a participant will play long games. This is ameliorated, however, by the risk-aversion score. The coefficient of the interaction between the buck-passing score and the risk-aversion score is positive (\(\beta =0.252, p<0.06\)). Furthermore, the two coefficients cancel each other out (\({\chi }^{2}=0.64, p>0.42\)). Thus, participants that have both high levels of both buck-passing scores and of risk-aversion do not play very differently than other participants, but participants that only have high buck-passing scores are more likely to play long, and probably too long, games. Hence, what is anticipated by the planners when deciding on whether or not to invest in playing a game is correct. Only in the case where low-risk aversion meets high buck-passing scores, games should be skipped.

The coefficients of the vigilance score and the interaction of the vigilance score with the risk-aversion score are both positive, suggesting that high level of vigilance is correlated with higher probability of disinvestment. The coefficients, however, are not statistically significant.

In addition, the coefficient of risk aversion is also positive and statistically significant (\(\beta =0.324, p<0.01\)). Thus, consistent with Musshof et al. (2013), high level of risk aversion is correlated with high probability of disinvestment.

To facilitate the interpretation of the results, Fig. 4 depicts the probability of disinvestment by round for two participants. The dashed line represents a participant that has the average values of all the variables. The solid line represents a participant that differs only by his buck-passing score. The buck-passing score of this participant is one standard deviation higher than the average. It can be seen that for each round, the probability that the participant with the high buck-passing score will disinvest is about 81% that of the participant with the average values.

Probability of quitting by round. Figure based on the results reported in column 1 of Table 4

In column 2, to test the robustness of the results, we add the same independent variables as in the second column of Table 5. The results remain almost unchanged. The buck-passing score is associated with lower probability of disinvestment (\(\beta =-0.193,p<0.07\)), while the interaction of the buck-passing score and the risk-aversion score is associated with higher probability of disinvestment (\(\beta =0.259,p<0.07\)). The two effects cancel each other out (\({\chi }^{2}=0.77, p>0.38\)).

5.3 Optimality of the number of rounds played

In the previous section, we show that participants with high scores of buck-passing are less likely to disinvest. This raises the question whether vigilance and buck-passing affect the optimality of the decisions that participants make.

We, therefore, define absolute-distance-from-optimality as our indicator of optimality. To measure the distance-from-optimality, we first find the optimal-number-of-rounds for each game by counting the number of rounds until the first round in which the round-prize is smaller than the trigger-prize. We then calculate the absolute-distance-from-optimality as the absolute difference between the number of rounds played and the optimal-number-of-rounds.

As an example for finding the distance from optimality, Fig. 5 depicts the decisions made by a participant in a low-variance-low-first-prize game. The thick line represents the round-prizes in each round and the dashed line represents the trigger-prizes. If the participant was following real-options theory, she should have disinvested in the sixth round, because that is the first round in which the round-prize dropped below the trigger-prize.

The participant, however, played until the tenth round. The participant's distance-from-optimal is, therefore, \(10-6=4\) rounds. For the entire sample, the average absolute-distance-from-optimality is 4.8 rounds, significantly greater than zero (t = 116.6, p < 0.01). A similar tendency to disinvest later than predicted by real-options theory in similar settings was also reported by Sandri et al. (2010) and Musshoff et al. (2013).

We use the distance from optimality as our proxy for optimal playing rather than the number of rounds played, because we look to control for the possibility that some participants played long games, because they had good draws rather than because they postponed disinvestments. In addition, we need to control for the possibility that some participants disinvest early, because they have a preference for short games and, therefore, would have disinvested early even if the round-prizes were above the trigger-prizes.

Note that the distance-from-optimality that we calculate is a lower bound on the optimal normative difference between the number of rounds that participants should have played and the number of rounds that they actually played. This is because we derive the trigger-prizes under the assumption that participants are risk-neutral, whereas most of the participants in our sample are risk-averse. As Musshof et al. (2013) show, risk-averse participants prefer early resolution of uncertainty. Given that most of the participants play games that are longer than expected, the optimal number of rounds that we calculate is a conservative estimate of the actual distance from the participants' optimal decision.

In column 1, we report the results of a regression that includes the buck-passing and vigilance scores, the risk-aversion score, the interaction of the buck-passing and vigilance scores with the risk-aversion score, and a dummy for decreasing-interest treatments. To control for the correlation between games played by the same participant, we add random effects and cluster the standard errors at the participants’ level. The results are summarized in column 1 of Table 6.

We find that the coefficient of the vigilance score is negative (\(\beta =-0.475, p<0.05\)). Thus, vigilant participants seem to play more consistently with the predictions of real-options theory, as the distance between their actual decisions and the optimal ones is smaller.

An increase in the risk-aversion score is also correlated with a tendency to play more consistently with the predictions of real-options theory (\(\beta =-1.361, p<0.01\)). This is an artefact, albeit a meaningful one. Normally, risk aversion should move away actual exit times from the optimal, risk-neutral ones. However, since respondents have an almost general tendency to exit too late, risk aversion reduces this tendency and moves actual exit times more towards the expected, risk-neutral ones. The coefficient of the buck-passing index is positive, thus suggesting that buck-passing participants postpone disinvestment even when disinvestment is optimal. The coefficient, however, is not statistically significant (\(\beta =0.387, p>0.33\)).

In column 2, we add the same controls as we added in column 2 of Tables 4 and 5. We find that adding controls does not significantly affect the coefficients of the vigilance score (\(\beta =-0.482, p<0.05\)) or the risk-aversion score (\(\beta =-1.395, p<0.01\)). The coefficient of the buck-passing score, however, becomes larger and marginally significant (\(\beta =0.562, p<0.09\)).

We, therefore, conclude that high scores of vigilance are correlated with playing more consistently with the predictions of real-options theory, whereas risk aversion seemingly has the same effect, but for different reasons (see above). High scores of buck-passing, on the other hand, are correlated with playing less consistently with the predictions of real-options theory. The differences between participants in buck-passing, vigilance, and risk aversion translate to significant differences in the payoffs. Participants with high scores of both vigilance and risk aversion earned, on average, 8.02 Euros from the game. Participants with high scores of buck-passing and low scores of risk aversion earned, on average, 17% less, 6.87 Euros. The differences are statistically significant (\(z=12.7, p<0.01\), Mann–Whitney test).

5.4 Robustness checks

To check the robustness of the results, we conducted several additional tests:

-

A.

Estimated the regressions of the likelihood of skipping a game using only observations from the compound-interest treatments (see: Appendix A)

-

B.

Added several variables to the regressions of the likelihood of disinvestment and of the distance from optimality (see: Appendix B).

-

C.

Removed observations of participants that made more than one switch between safe and risky bets in the Holt and Laury (2002) procedure (see: Appendix C).

-

D.

Estimated the regressions using only observations from the first game of each participant, to remove any effects of learning (see: Appendix D).

-

E.

The results of estimating the distance from optimality could have been affected by the decision to participate in the game. We, therefore, estimate a two-stage Heckman procedure to estimate the distance from optimality conditional on deciding to participate in the game (see: Appendix E).

We find that the results are robust to these additional testings.

6 Summary and brief discussion

Our findings are highly consistent with (a) the effects expected based on the conflict theory of decision-making (buck-passing and vigilance), (b) the expected effects of risk aversion, and (c) a planer-doer model.

Buck-passers, indeed, hold on for longer than others, vigilant players act more rationally than the rest, and risk-averters exit earlier than the others. The effects of the interactions between risk aversion and buck-passing and between risk aversion and vigilance are quite persistent and play together very well. If someone is a buck-passer and has a low level of risk aversion, he becomes a ‘lousy’ doer and plays on for a very long time even if this behavior is, in fact, not advisable. This is, however, anticipated by some planners, that seem to ‘know’ their doers quite well, by skipping significantly more games in that constellation. This is a nice interplay between the conflict theory of decision-making and a planner–doer perspective.

7 Conclusions and implications

Above, we use a questionnaire that is based on the conflict theory of decision-making to study individuals' attributes that are likely to be correlated with decision-making. The theory of decision-making suggests that making decisions is stressful because choosing one alternative implies giving up on the other alternatives (Janis and Mann 1977; Mann et al. 1997; Loewenstein and Lerner 2003). The theory also suggests that individuals differ in their ability to handle this stress, with some individuals making efficient decisions and some having maladaptive styles of handling the stress.

According to the theory, vigilant individuals are able to handle the stress well and make efficient decisions. Buck-passing individuals, on the other hand, find it difficult to handle the stress. Consequently, they tend to buck-pass the decision to someone else or to a later period.

The theory also suggests that risk-averse individuals are more likely than risk-tolerant individuals to collect information and process it. This is because the theory predicts that individuals that find the cost of making a false decision are large are more likely to process information than participants that view the cost as low.

We combine this theory with a planner–doer model, assuming that only the doers are affected by the stress of decision-making. Risk aversion might be important for both a planner and a doer, but perhaps doers, with their short-term perspective are more strongly affected. Nevertheless, we have evidence for all our theorizing, since risk aversion, buck-passing, vigilance, and the interplay of those have the expected effects.

Thus, our results suggest that the theory of decision-making can be used as a basis for predicting individuals' choices. The results can also assist in identifying scenarios that are prone to postponement of decisions. This is particularly important in financial markets where investors that are affected by the disposition to hold losing assets too long can accumulate significant losses (Shefrin and Statman 1985; Odean 1998).

Furthermore, the results suggest that tendencies to postpone decisions are related to personality characteristics (individual decision-making styles). Indeed, our results are a first, small, but important step to better understand the impact of these styles of decision-making on the disposition to delay making decisions. Indeed, if stable individual styles play a prominent role in decision-making, knowledge and training might have only modest effects on individuals' procrastination tendencies. It is left to study; however, the correlation between education and the style of decision-making, as some studies suggest that education and intelligence can affect economic decisions and outcomes (Blinder and Krueger 2004; Ameriks et al. 2007a, b).

In addition, it is necessary to specifically study the relationships between procrastination, buck-passing, vigilance, and the tendency to get committed to past decisions (Post et al. 2008, Khavul et al. 2009). Indeed, psychologists find that buck-passing traits are correlated with procrastination. It might, therefore, be that buck-passing, procrastination, and commitment to past decisions are all correlated and affected by overlapping personality traits. This requires an experimental scenario where all those tendencies are about equally important, an interesting task for future research.

Thus, an observed postponement of decisions might be the outcome of several traits. For example, in our settings, it is possible that identifying participants as vigilant also has the interpretation of them having low propensity to become committed to their past decisions. A better understanding of the correlations between different motives for delaying decisions can, therefore, assist in both predicting and minimizing the effects of instances in which individuals decide not to decide (Samuelson and Zeckhauser 1988).

Notes

Even though their study is about procrastination that has just been argued to be irrelevant in our decision situation, their finding should be broad enough to also hold in our context.

Another reason for the popularity of planner-doer models is that research in neurology has shown that they can be given interpretation in terms of neurological processes (Camerer, 2007).

Please note the difference between buck-passing and procrastination. Buck-passing individuals often postpone decisions, but they do it for a different motive than procrastinators. Consider the following example: an individual enters a shop and is given a choice between two brands. Both brands satisfy her tastes and both are on sale. A procrastinator will not hesitate before making a choice, because the choice does not involve inter-temporal preferences and there is no actual ‘task’ to be done. A buck-passer, on the other hand, would like somebody else to make the decision for her, and if there is no one to ask, she will usually decide to keep the status quo, i.e., not to buy (Shafrir et al., 1993).

We used Z-Tree to program the experiment (Fischbacher, 2007).

At the time of the experiment, the average exchange rate was 1.42 US Dollars for 1 Euro.

About 18% of the participants made more than one switch between the "safe" and the "risky" gambles in the Holt and Laury (2002) test. In these cases, we calculated the participants' risk aversion according to the last switch from the safe to risky option that they made, thus giving these participants the maximum risk aversion score implied by their responses.

References

Akerlof, George A. 1991. Procrastination and Obedience. American Economic Review 81 (2): 1–19.

Ameriks, John, Andrew Caplin, and John Leahy. 2007a. Retirement Consumption: Insights from a Survey. Review of Economics and Statistics 89 (2): 265–274.

Ameriks, John, Andrew Caplin, and John Leahy. 2007b. Measuring Self-Control Problems. American Economic Review 97 (3): 966–972.

Angeletos, George-Marios, David Laibson, Andrea Repetto, and Jeremy Tobacman. 2001. The Hyperbolic Consumption Model: Calibration, Simulation and Empirical Evaluation. Journal of Economic Perspectives 15 (3): 47–68.

Ariely, Dan, and Klaus Wertenbroch. 2002. Procrastination, Deadlines and Performance: Self Control by Precommitment. Psychological Science 13 (3): 219–224.

Blinder, S.Alan, and Alan B. Krueger. 2004. What does the public know about economic policy, and how does it know it? Brookings Papers on Economic Activity 35: 327–397.

Brennan, Michael J., and Eduardo S. Schwartz. 1985. Evaluating Natural Resource Investment. Journal of Business 58 (2): 135–157.

Brown, Jac, and Ng Reuben. 2012. Making Good Decisions: The Influence of Culture, Attachment Style, Religiosity, Patriotism and Nationalism. Global Journal of Human Social Science, Arts and Humanities 12 (10): 37–45.

Burmeister, Katrin, and Christian D. Schade. 2007. Are entrepreneurs’ decisions more biased? An experimental investigation of the susceptibility to status quo bias. Journal of Business Venturing 22: 340–362.

Camerer, Colin F. 2007. Neuroecomics: Using Neuroscience to Make Economic Prediction. Economic Journal 117 (519): C26–C42.

Della Vigna, Stefano, Ulrike Malmendier. 2004. Contract Design and Self Control: Theory and Evidnence, Quarterly Journal of Economics 119(2), 353–402

DeTienne Dawn, R., Dean A. Shepherd, and Castro O. Julio. 2008. The Fallacy of 'only the Strong Survive:' The Effects of Extrinsic Motivation on the Persistence of Underperforming Firms. Journal of Business Venturing 23: 528–546.

Dixit, Avinash. 1991. Irreversible Investment with Price Ceilings. Journal of Political Economy 99 (3): 541–557.

Dixit, Avinash K. and Robert S. Pindyck. 1994. Investment Under Uncertainty, (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press).

Engin, Deniz M. 2006. The Relationships among Coping with Stress, Life Satisfaction, Decision Making Styles and Decision Self-Esteem: An Investigation with Turkish University Students. Social Behavior and Personality: An International Journal 34 (9): 1161–1170.

Fioretti, Guido. 2009. Passing the Buck in the Garbage Can Model of Organizational Choice. Working Paper.

Fischbacher, Urs. 2007. Z-Tree: Zurich Toolbox for Ready-Made Economic Experiments. Experimental Economics 10 (2): 171–178.

Folger, Joseph P., Marshall Scott Poole, and Randall K. Stutman. 1997. Working Through Conflict. New York: Longman.

Frederic, Shane, George Loewenstein, and Ted O'Donoghue. 2002. Time Discounting and Time Preferences: A critical Review. Journal of Economic Literature 40 (2): 351–401.

Fudenberg, Drew, and David K. Levine. 2006. A Dual-Self Model of Impulse Control. American Economic Review 96 (5): 1449–1476.

Gorodetzky, Hadas, Barbara J. Sahakian, Trevor W. Robbins, and Karen D. Ersche. 2011. Differences in Self-Reported Decision-Making Styles in Stimulant-Dependent and Opiate-Dependent Individuals. Psychiatry Research 186 (2–3): 437–400.

Gul, Faruk, and Wolfgang Pesendorfer. 2004. Self Control and the Theory of Consumption. Econometrica 72 (1): 119–158.

Heredia, Ramón Alzate, and Sáez de, Francisco Laca Arocena and José Valencia Gárate. 2004. Decision-Making Patterns, Conflict Styles, and Self-Esteem. Psicothema 16: 110–116.

Holt, Charles A., and Susan K. Laury. 2002. Risk Aversion and Incentives Effects. American Economic Review 92 (5): 1644–1655.

Janis, Irving, and Leon Mann. 1977. Decision Making: A Psychological Analysis of Conflict, Choice and Commitment. NY, NY: The Free Press.

Keinan, G. 1987. Decision Making Under Stress: Scanning of Alternatives Under Controllable and Uncontrollable Threats. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 52: 639–644.

Khavul, Sussana, Livia Makoczy, Rachel Croson and Ronit Yitshaki. 2009. The Moderating Effect of Goal Specificity on Escalation of Commitment in Entrepreneurial Firm Exit. Working Paper.

Lazarus, Richard S., and Susan Folkman. 1984. Stress. Appraisal and Coping, New York: Springer.

Loewenstein, George, and Drazen Prelec. 1992. Anomalies in Intertemporal Choice: Evidence and an Interpretation. Quarterly Journal of Economics 107 (2): 573–597.

Loewenstein, George and Jennifer S. Lerner. 2003. The Role of Affect in Decision Making. in R.J Davidson, K.R. Scherer and H.H. Goldsmith (eds.), Handbook of Affective Sciences, 619 – 642.

Loneck, Barry M., and Lenore A. Kola. 1989. Using the Conflict-Theory Model of Decision Making to Predict Outcome in the Alcoholism Intervention. Alcoholism Treatment Quarterly 5 (3): 119–136.

Mackworth, N.H. 1948. The breakdown of vigilance during prolonged visual search. Quarterly Journal of Experimental Psychology 1: 6–21.

Mann, Leon, Paul Burnett, Mark Radford, and Steve Ford. 1997. The Melbourne Decision Making Questionnaire: An Instrument for Measuring Patterns for Coping with Decisional Conflict. Journal of Behavioral Decision Making 10 (1): 1–19.

Mann, Leon, Mark Radford, Paul Burnett, Steve Ford, Michael Bond, Kwok Leung, Hiyoshi Nakamura, Graham Vaughan, and Kuo-Shu Yang. 1998. “Cross-Cultural Differences in Self-Reported Decision Making Style and Confidence. International Journal of Psychology 33 (5): 325–335.

McDonald, Robert, and Daniel Siegel. 1986. The Value of Waiting to Invest. Quarterly Journal of Economics 101 (4): 707–728.

Musshoff, Oliver, Martin Odening, Christian Schade, Syster Christin Maart-Noelck, and Serena Sandri. 2013. Inertia in disinvestment decisions: Experimental evidence. European Review of Agricultural Economics 40: 463–485.

Odean, Terrance. 1998. Are Investors Reluctant to Realize their Losses? Journal of Finance 53 (5): 1775–1798.

O'Donoghue, Ted, and Matthew Rabin. 1999. Incentives for Procrastination. Quarterly Journal of Economics 114 (3): 769–816.

O'Donoghue, Ted, and Matthew Rabin. 2001. Choice and Procrastination. Quarterly Journal of Economics 116 (1): 121–160.

O’Hare, David. 1992. The Artful Decision Maker: A Framework Model for Aeronautical Decision Making. The International Journal of Aviation Psychology 2: 175–191.

Philips, James G., and Linnea Reddie. 2007. Decisional Style and Self-Reported Email Use in the Workspace. Computers in Human Behavior 23 (5): 2414–2428.

Post, Thierry, Martijn J. van den Assem, Giudo Baltussen, and Richard H. Thaler. 2008. Deal or No Deal? Decision Making under Risk in Large-Payoff Game Show. American Economic Review 98 (1): 38–71.

Prelec, Dražen. and Ronit Bodner. 2005. Self-signaling and self-control. in G. Loewnestein, D. Read and R.F. Baumeister (eds.) Time and Decision (New York, NY: Russell Sage Press).

Samuelson, William, and Richard Zeckhauser. 1988. Status Quo Bias in Decision Making. Journal of Risk and Uncertainty 1: 7–59.

Sandri, Serena, Christian Schade, Oliver Musshoff, and Martin Odening. 2010. Holding on for too Long? An Experimental Study on Inertia in Entrepreneurs' and Non-Entrepreneurs' Disinvestment Choices. Journal of Economic Behavior and Organization 76: 30–44.

Shafrir, Eldar, Itamar Simonson, and Amos Tversky. 1993. Reason Based Choice. Cognition 49: 11–36.

Shefrin, Hersh, and Meir Statman. 1985. The Disposition to Sell Winners Too Early and Ride Losers Too Long: Theory and Evidence. Journal of Finance 40 (3): 777–790.

Sirois, Fuchsia M. 2007. I'll Look After my Health, Later: A Replication and Extension of the Procrastination-Health Model with Community-Dwelling Adults. Personality and Individual Differences 45 (1): 15–26.

Sivanathan, Niro, Daniel C. Molden, Adam D. Galinsky, and Ku Gillian. 2008. The Promise and Peril of Self-Affirmation in De-Escalation of Commitment. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Process 107: 1–14.

Thaler, Richard. 1981. Some Empirical Evidence on Dynamic Inconsistency. Economic Letters 8: 201–207.

Thaler, Richard H., and Hersh M. Shefrin. 1981. An Economic Theory of Self-Control. Journal of Political Economy 89 (2): 392–406.

Titman, Sheridan. 1985. Urban Land Prices Under Uncertainty. American Economic Review 75 (3): 505–514.

Weeds, Helen. 2002. Strategic Delay in a Real Option Model of R&D Competition. Review of Economic Studies 69: 729–747.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Appendices

Appendix A: regression of likelihood of skipping games, using data from compound-interest treatments

In the paper, we estimate the probability that a participant skips a game using the full set of observations. However, none of the participants skipped a game in the negative-interest treatment. As a robustness check, we therefore remove all the observations from the negative-interest treatment and leave only observations from the compound-interest treatment.

To estimate the probability that a participant skips a game, we estimate both linear probability models (LPM) and probit models. To control for the possibility that decisions made by the same participant are correlated, we augment the model with random-effects and cluster the standard errors at the participants' level.

The dependent variable is a dummy that equals 1 if a participant skipped a game and 0 if she invested to play the game. In column 1 (linear probability model) and column 3 (probit model) the only independent variables are the main variables of interest: the buck-passing and vigilance scores, the risk aversion score based on the Holt and Laury (2002) procedure, and the interaction of the buck-passing and vigilance scores with the risk aversion score. For simplicity, we focus on the results of the LPM model (column 1). The results of the probit model are qualitatively similar. It can be observed that the coefficient of the buck-passing index is positive (\(\beta =0.005, p<0.09\)) and marginally significant. Therefore, participants with high buck-passing scores are more likely to skip (Table 7).

The coefficients of the other variables are not statistically significant, but the results suggest that an increase in the risk-aversion scores might be associated with a decrease in the likelihood of skipping games. As a further test, in column 2 (LPM model) and 4 (probit model) we add independent variables that control for the attributes of the games and for the participants’ characteristics. These include: The log of the investment-cost which is either 10,000 or 15,000 points, the log of the disinvestment-prize which is either 11,000 or 16,000 points, the log of the variance which is either 200 or 1000 points, the log of the first-prize which is either 1000 or 1500 points, the maximum and minimum prizes a participant could win in the game, the participants' age, a man dummy that equals 1 if a participant is a man and 0 if the participant is a woman, a student dummy that equals 1 if a participant is a student and 0 otherwise and a German-born dummy that equals 1 if a participant was born in Germany and 0 otherwise.

We find again that an increase in the buck-passing score is associated with an increase in the likelihood of skipping games (\(\beta =0.010, p<0.05\)). Also, as we find in the paper, the coefficient of the interaction between the buck-passing score and the risk-aversion score is negative, although it is not significant in this specification (\(\beta =-0.010, p<0.05\)).

Appendix B: adding several additional variables to the regressions of the likelihood of disinvestment and the distance from optimality

In the paper, we use the same control variables in all the regressions. However, for the regressions of the likelihood of disinvestment (Table 5 in the paper) and the regression of the distance from optimality (Table 6 in the paper), there are several other control variables that may have explanatory power. In this section, we estimate these regressions again, after adding these control variables.

In column 1 of Table 8, we report the results of a Cox regression of the hazard of disinvestment in a given round. The dependent variable is the number of rounds until a participant disinvested. The main independent variables are the buck-passing and vigilance scores, the risk aversion score based on the Holt and Laury (2002) procedure, and the interaction of the buck-passing and vigilance scores with the risk aversion score. In addition, we also include the following controls: The log of the investment-cost which is either 10,000 or 15,000 points, the log of the disinvestment-prize which is either 11,000 or 16,000 points, the log of the variance which is either 200 or 1000 points, the log of the first-prize which is either 1000 or 1500 points, the maximum and minimum prizes a participant could win in the game, the participants' age, a man dummy that equals 1 if a participant is a man and 0 if the participant is a woman, a student dummy that equals 1 if a participant is a student and 0 otherwise, a German-born dummy that equals 1 if a participant was born in Germany and 0 otherwise, the distance-to-trigger-prize which is the difference between the round prize and the trigger prize below which the participant should disinvest and the expected number of rounds the participant should have played if he would have followed real-option theory.

We find that adding the trigger-prizes and the expected number of rounds to the list of independent variables does not change the main results. We find that the coefficient of the buck-passing score is negative (\(\beta =-0.189, p<0.08\)), suggesting that an increase in the buck-passing score is correlated with a smaller probability of disinvesting. In other words, the higher the of buck-passing score, the higher the probability that a participant will play long games. This is ameliorated, however, by the risk-aversion score. The coefficient of the interaction between the buck-passing score and the risk aversion score is positive (\(\beta =0.255, p<0.08\)). Furthermore, the two coefficients cancel each other out (\({\chi }^{2}=0.75, p>0.39\)). Thus, participants that have high levels of both the buck-passing score and the risk-aversion score do not play very differently than other participants, but participants that only have high buck-passing scores are more likely to play long, and probably too long, games.

In column 2, we report the results of a regression of the distance from optimality. The dependent variable is the absolute-distance-from-optimality. To measure the distance-from-optimality, we first find the optimal-number-of-rounds for each game by counting the number of rounds until the first round in which the round-prize was smaller than the trigger-prize. We then calculate the absolute-distance-from-optimality as the absolute difference between the number of rounds played and the optimal-number-of-rounds.

The independent variables are the same as in the regression of column 1. We find that the coefficient of the vigilance score is negative (\(\beta =-0.490, p<0.04\)). Thus, vigilant participants seem to play more consistently with the predictions of real-options theory, as the distance between their decisions and the optimal ones is smaller.

An increase in the risk-aversion score is also correlated with a tendency to play more consistently with the predictions of real-options theory (\(\beta =-1.400, p<0.01\)). The coefficient of the buck-passing index is positive, and marginally significant (\(\beta =0.571, p>0.09\)). It therefore seems buck-passing participants play less consistently with the predictions of real-options theory than other participants.

To summarize, participants with high scores of vigilance tend to disinvest closer to the round predicted by real-options theory. Participants with high levels of buck-passing, on the other hand, disinvest a large number of rounds away from the round predicted by real options theory. Combined with the results of the regression on the likelihood of disinvestment in a given round, we can say that they play less consistently because they tend to play games that are too long.

Appendix C: estimating regressions after removing observations of participants that made more than one switch in the Holt and Laury (2002) procedure

In the paper, we estimate the regressions using the full sample. However, some of the participants made more than one switch between safe and risky bets in the Holt and Laury (2002) procedure. This suggests that these participants either have problems with understanding the instructions, or that they make irrational decisions. To minimize the concern that participants that misunderstood instructions/made irrational decisions affect the results, we estimated the regressions after removing these participants from the sample.

The independent variables in all the regressions are the same. The main independent variables are the buck-passing and vigilance scores, the risk aversion score based on the Holt and Laury procedure, and the interaction of the buck-passing and vigilance scores with the risk aversion score. In addition, we also include the following controls: The log of the investment-cost which is either 10,000 or 15,000 points, the log of the disinvestment-prize which is either 11,000 or 16,000 points, the log of the variance which is either 200 or 1000 points, the log of the first-prize which is either 1000 or 1500 points, the maximum and minimum prizes a participant could win in the game, the participants' age, a man dummy that equals 1 if a participant is a man and 0 if the participant is a woman, a student dummy that equals 1 if a participant is a student and 0 otherwise, and a German-born dummy that equals 1 if a participant was born in Germany and 0 otherwise.

In column 1 of Table 9, we report the results of a regression of the likelihood that a participant skipped a game. The dependent variable is a dummy that equals 1 if the participant skipped a game and 0 if he invested to play the game. We estimate a random effects linear probability model, with robust standard errors, clustered at the participant level.

We find, as we find in the paper, that the buck-passing score is correlated with a higher probability of skipping games (\(\beta =0.007,p<0.06\)). The coefficient of the interaction of the buck-passing score with the risk-aversion score is negative (\(\beta =-0.005,p<0.16\)), although it is not statistically significant. Thus, while participants with high scores of buck-passing are more likely to skip, an increase in their risk-aversion scores makes them more likely to invest in playing.

In column 2, we report the results of a Cox regression of the hazard of disinvestment in a given round. The dependent variable is the number of rounds until a participant disinvested.

We find that the coefficient of the buck-passing score is negative (\(\beta =-0.178,p<0.10\)), while the coefficient of the interaction between the buck-passing and the risk-aversion scores is positive (\(\beta =0.245,p<0.09\)). In addition, the coefficient of the risk-aversion score is positive (\(\beta =0.340,p<0.02\)).

Thus, for each round, participants with high score of buck-passing are less likely to disinvest. However, when a participant’s risk-aversion score increases, the likelihood that she disinvests increases.

In column 3, we report the results of a random effects linear regression of the distance from optimality. The dependent variable is the absolute-distance-from-optimality. To measure the distance-from-optimality, we first find the optimal-number-of-rounds for each game by counting the number of rounds until the first round in which the round-prize was smaller than the trigger-prize. We then calculate the absolute-distance-from-optimality as the absolute difference between the number of rounds played and the optimal-number-of-rounds. The standard errors are clustered at the participants’ level.

We find that the coefficient of the buck-passing index is positive (\(\beta =0.657,p<0.06\)). The coefficients of the vigilance (\(\beta =-0.240,p<0.10\)) and the risk-aversion \(\beta =-1.415,p<0.01\)) scores, on the other hand, are negative. Thus, as we find in the paper, participants with high scores of buck-passing tend to play games that are too long. Consequently, they disinvest long after the round suggested by real-options theory. Participants with high scores of risk-aversion and of vigilance, on the other hand, tend to play more consistently with the predictions of real options theory than other participants.

Appendix D: estimating regressions using observations from the first game

Each participant played six games. In this section, we show that the results are not driven by experience. For this, we re-estimate the regressions we estimated in the paper, this time using data only from the first game that each participant played. This should also alleviate the concern that our results were affected by the correlations between games played by the same participants.

The independent variables in all the regressions are the same. The main independent variables are the buck-passing and vigilance scores, the risk aversion score based on the Holt and Laury (2002) procedure, and the interaction of the buck-passing and vigilance scores with the risk aversion score. In addition, we also include the following controls: The log of the investment-cost which is either 10,000 or 15,000 points, the log of the disinvestment-prize which is either 11,000 or 16,000 points, the log of the variance which is either 200 or 1000 points, the log of the first-prize which is either 1000 or 1500 points, the maximum and minimum prizes a participant could win in the game, the participants' age, a man dummy that equals 1 if a participant is a man and 0 if the participant is a woman, a student dummy that equals 1 if a participant is a student and 0 otherwise, and a German-born dummy that equals 1 if a participant was born in Germany and 0 otherwise.

In column 1, we report the results of a regression of the likelihood that a participant skipped a game. The dependent variable is a dummy that equals 1 if the participant skipped a game and 0 if he invested to play the game. We estimate a linear probability model, with robust standard errors.

We find that both the vigilance score (\(\beta =0.015, p<0.07\)) and buck-passing score (\(\beta =0.029, p<0.10\)) are correlated with an increase in the likelihood of skipping games. At the same time, the coefficients of the interactions of risk-aversion with vigilance (\(\beta =-0.014, p<0.09\)) and with buck-passing (\(\beta =-0.027, p<0.12\)) are negative.

Thus, in the first round that they play, it seems that participants with high levels of either buck-passing or vigilance are more likely to skip games. However, as they become more risk-averse, they are less likely to skip. Indeed, in both the case of vigilance (\(F=0.01, p>0.92\)) and buck-passing (\(F=0.04, p>0.83\)), the coefficient of the interaction with the risk-aversion score is not statistically different than the main effect.

In column 2, we estimate a regression of the hazard that a participant disinvests in a given round. The dependent variable is the round in which each participant disinvested. To estimate the hazard, we use a Cox model, and we use robust standard errors.

Consistent with the findings we report in the paper, the buck-passing score is correlated with a decrease in the likelihood that a participant disinvests in a given round (\(\beta =-0.255, p>0.29\)). Vigilance is correlated with an increase in the likelihood that a participant disinvests in a given round (\(\beta =0.047, p>0.80\)). However, unlike what we find in the paper, when we use data only from the first game, the results are not statistically significant. This can probably be explained by the relatively small number of observations.

In column 3, we estimate a linear regression with robust standard errors of the distance from optimality (Table 10). The dependent variable is the absolute-distance-from-optimality. To measure the distance-from-optimality, we first find the optimal-number-of-rounds for each game by counting the number of rounds until the first round in which the round-prize was smaller than the trigger-prize. We then calculate the absolute-distance-from-optimality as the absolute difference between the number of rounds played and the optimal-number-of-rounds.