Abstract

Background

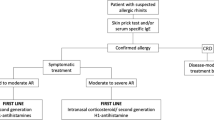

Allergic rhinitis (AR) continues to increase in incidence and is the most common allergic disease. If abstention of the allergen triggering substances is not possible, allergen-specific immunotherapy (AIT) as causal treatment or a drug therapy with mast cell stabilizers, antihistamines (AHs), glucocorticoids (GCs), leukotriene (LT) receptor antagonists and decongestants is indicated. Despite these diverse therapeutic options, studies on the real-life care situation of patients with AR regularly show that a considerable proportion of patients do not feel adequately treated with monotherapy of the usual drugs and therefore use several preparations with different active ingredients simultaneously and in various combinations. However, such parallel applications of several active ingredients are normally not tested in approval studies and therefore carry a potential risk of side effects or lack of efficacy.

Methods

For the present publication, a focused literature search in PubMed, Livivo and on the World Wide Web for the previous 20 years (period 01/1999 to 01/2020) was carried out. This literature search included original and review articles in German or English. A further analysis of current publications was also conducted for German-language journals that are not available in international literature databases.

Results

AHs and nasal GCs represent the therapeutic standard in AR. Their efficacy is well documented for several preparations. The evidence for combination therapies is documented very well for a fixed combination of azelastine and fluticasone (MP29-02). For the simultaneous use of non-fixed combined monopreparations, only a few efficacy and safety studies based on modern evidence criteria exist.

Conclusion

The free combination therapies of mast cell stabilizers, decongestants, AHs and nasal GCs, frequently used in the routine care of patients with AR, cannot be recommended because they are not evidence-based. Due to the fact that over-the-counter antiallergic drugs are not reimbursable in Germany, there is no medical supervision of the therapy. In addition, there are doubts about appropriate treatment, especially of patients with persistent rhinitis with severe symptoms, as these patients often use several preparations at the same time to alleviate their symptoms.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Allergic rhinitis (AR) affects approximately 10–20% of the global population [1] and is often associated with other allergic comorbidities such as asthma and atopic eczema. At present, drug-based symptomatic therapy of AR mainly involves the administration of antihistamines (AHs), glucocorticoids (GCs), mast cell stabilizers, leukotriene (LT) receptor antagonists, and decongestants.

Numerous studies have shown that the everyday care situation of AR patients is inadequate. Insufficient symptom control and adverse effects cause frequent changes in therapy and treatment approaches without proven evidence [2]. More than 29% of patients do not know what kind of medication they are taking, 26% switch between different medications several times to find an effective one, 42% feel confused by the multitude of different medications, and 64% only take their AR medication in the case of very severe symptoms until improvement occurs [2, 3]. These approaches are in marked contrast to current guidelines, which provide prophylactic, problem-oriented, and continuous treatment [4,5,6]. International studies also show that this situation can be improved by providing patients with comprehensive information and simple treatment regimens adapted to their lifestyle [7, 8].

AR patients report a variety of short-term AR symptom exacerbations, which they usually treat as needed [9]. Even those patients who are on continuous therapy often report periods without sufficient symptom control, which can be directly or indirectly attributed to an incorrect choice of therapy, undetected concomitant diseases (e.g., nasal hyperreactivity) or an incorrect diagnosis (e.g., non-allergic rhinitis) [9, 10].

The app “MASK Allergy Diary”, funded by the EU Commission and developed by the ARIA working group of the World Health Organization (WHO), provides data throughout Europe on the actual treatment of AR patients under routine conditions in the care reality of the respective country [11]. Again, it was shown that patients who feel inadequately treated use a variety of different AR medications, frequently switch back and forth between different preparations, preparation groups or combinations, and do not take the medication according to guideline recommendations. An AR clinical decision support system (CDSS) is designed to help improve this situation and align patient preferences for therapy with current guideline recommendations [5, 12].

Overview of the different active ingredient classes and their free and fixed combinations

Decongestants (α-sympathomimetics)

For the acute treatment of AR, α sympathomimetics are used, which bind to and activate α‑adrenoreceptors. The result is a vasoconstriction of the nasal mucosa, which leads to a reduced filling of the capacity vessels and thus to a decongestion of the mucous membranes.

The substances can be administered topically as well as systemically. An advantage of decongestants is their rapid onset of action. However, they only reduce the nasal obstruction and no further symptoms. Side effects of systemic medication include tachycardia, restlessness, insomnia and hypertension [13]. Nasal dryness and sneezing may occur with topical use of decongestants. Long-term use can also lead to the development of rhinopathia medicamentosa. Accordingly, therapy with decongestant should not last longer than three to five days [1].

Mast cell stabilizers

The substances cromoglycate and nedocromil have a stabilizing effect on the histamine-producing mast cells by blocking their degranulation process [14]. An advantage of these substances is their good tolerability and the low side effect profile, so that they are often used in infants and pregnant or breastfeeding women. A disadvantage of this form of therapy is the need for four applications a day, as this often leads to compliance problems. In addition, mast cell stabilizers show a weaker effect on nasal symptoms compared to other pharmacological substances such as AHs and GCs. Accordingly, they only play a minor role in the therapy of AR [1].

Leukotriene receptor antagonists

It is known that in the allergic inflammation cascade, besides histamine and various cytokines, LT such as cysteine-leukotrienes (CysLT) play a decisive role, especially in patients with persistent AR. LTs lead to a strong bronchoconstriction, increased capillary permeability and increased secretion of the mucous glands [15]. LT receptor antagonists prevent this process by either blocking the receptor itself as competitive inhibitors (montelukast, zafirlukast, pranlukast) or by inhibiting the enzyme 5‑lipoxygenase (zileuton), which is involved in the formation of LT. In Germany, only montelukast is approved as a LT receptor antagonist for the treatment of bronchial asthma in adults and children. Recently, the approval of montelukast has been extended to AR in asthmatic patients, but not as a therapy for AR without comorbid asthma.

Although LT receptor antagonists are more effective than placebo in the treatment of AR, they are less potent than oral H1 AHs [16]. In 2009, Lehtimäki et al. investigated the effectiveness of montelukast as a monotherapy in a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study in 45 pollen allergic patients with symptoms in the upper and lower respiratory tract and outside the respiratory tract (conjunctivitis, oral allergy syndrome, urticaria). Differences between placebo and verum were only found in the consumption of inhaled β2‑agonists (LABA) in patients with asthmatic complaints. A significant improvement in the symptoms of AR and other allergic symptoms could not be observed [17].

Antihistamines

AHs block cellular histamine receptors and thus reduce the effect of histamine in tissue. Histamine exerts its effect on the cells via four histamine receptors (H1, H2, H3, and H4). Since the H1 receptors are mainly responsible for the immediate allergic reaction, only H1 AHs are currently used for the treatment of AR. However, initial clinical trials of the efficacy of H3 AHs also suggest a potential benefit in reducing nasal symptoms, while H4 AHs have so far only been used in animal testing [18].

A basic distinction is made between first- and second-generation H1 AHs. The first generation of H1 AHs has a pronounced sedative effect, which can have a negative impact on performance and motor skills [19]. Second-generation H1 AHs, on the other hand, can only pass the blood–brain barrier to a limited extent due to their hydrophilic character and therefore have little or no sedative properties.

H1 AHs are available for both systemic and topical use. The advantage of both forms of application is that they effectively improve most symptoms of AR, for example rhinorrhea, pruritus and ocular symptoms. However, nasal obstruction is better reduced by topical application. Topical AHs, such as azelastine, have a particularly rapid onset of action within about 15 min and are therefore particularly useful for acute symptoms [20]. However, the disadvantage is the shorter duration of action, so that twice daily application is necessary, whereas most oral AHs can be taken in a daily dose.

Accordingly, second-generation drugs are preferred in the treatment of AR [1]. The newer AHs such as levocetirizine, desloratadine, fexofenadine, ebastine, mizolastine, rupatadine [21,22,23] olopatadine [24], and bilastine [25,26,27] are more advanced forms of second-generation AHs and are sometimes referred to as third-generation AHs. These modern AHs should have other anti-inflammatory properties in addition to the H1-blocking effect.

However, the current data situation can by no means prove a superiority of a certain antihistamine over other AHs from head-to-head comparisons. In studies comparing different AHs in intermittent AR, no statistically detectable differences in efficacy and safety were found [28].

There is no consistent result when comparing the potency of AHs with intranasal GCs. Most studies, however, ascribe better efficacy to intranasal GCs [1, 6, 29]. Only a few studies show similar efficacy for both types of therapy [30].

Topical glucocorticoids

Topical GCs bind to intracellular glucocorticoid receptors (GR) and thereby activate the receptor complex. The effect of the GCs is mediated by cytoplasmic receptors that are found in numerous cells [31]. GCs can either activate or suppress the transcription of different target genes and thereby increase or inhibit specific mRNA production. Thus, the transcription of numerous inflammatory mediators (e.g., cytokines, chemokines) can be suppressed or the production of anti-inflammatory mediators and other signal proteins (e.g., lipocortin‑1 and β2-adrenoceptors) can be increased [32].

Interestingly, besides these time-consuming mechanisms, there are receptor-independent immediate effects. For example, the vascular exudation in the allergic immediate phase reaction can be significantly reduced as early as 5–10 min after application of intranasal GCs and the allergen-induced expression of the adhesion molecule E‑selectin can be significantly inhibited after only 30 min [31, 32].

The main advantage of intranasal GCs is that they effectively suppress all nasal symptoms. GCs are generally well tolerated and local side effects are usually limited to epistaxis, nasal dryness, irritation of the throat and headache. Systemic side effects such as those associated with systemic administration of GCs are rare in modern intranasal GCs, and growth inhibition in children has so far only been demonstrated with the administration of beclomethasone dipropionate [33]. Nevertheless, the growth of children should be checked regularly with long-term administration. A disadvantage of GCs is that, unlike AHs, they have a later maximum onset of action. Due to their good efficacy profile, intranasal GCs are currently the first choice for the treatment of AR.

Comparison of different treatment strategies

In a meta-analysis, various drugs approved for the treatment of AR were compared with regard to their symptom reduction (overview of drug groups in Table 1) when used in the approved dosage [34, 35].

The evaluation included data from 54 randomized, placebo-controlled studies with more than 14,000 adults and 1580 children with AR. For the evaluation of the total nasal symptom score (TNSS), the treatment for reduction of symptoms in intermittent AR resulted in the following: nasal AHs = −22.2%; oral AHs = −23.5%; topical GCs = −40.7%; placebo = −15.0%. For persistent AR, these reductions were −51.0% for oral AHs, −37.3% for topical GCs, and −24.8% for placebo, although the data situation is significantly more limited for persistent AR. There are a number of other studies that also address the comparison of different medications for the treatment of AR and lead to similar results [36,37,38].

In summary, intranasal GKs are most effective in the treatment of AR.

Free combinations of different active ingredients

Many AR patients do not feel sufficiently treated with the existing monotherapies [2, 3, 9, 10] and therefore resort to combinations of different preparations [39, 40]. However, approval studies usually do not investigate the safety or efficacy of combinations of different drugs. In the following, information on those combinations for which literature references are available is summarized.

Combinations of an oral antihistamine and a LT receptor antagonist are only more effective than oral AHs alone in AR patients with comorbid asthma, which is why the agents should be used in parallel only in these patients [16]. Several studies have been conducted on the combination of AHs and LT receptor antagonists [41,42,43,44]. An advantage of leukotriene LT receptor antagonists seems to be that they are effective in both asthma and AR, so that patients with a comorbidity benefit from them. The active substance montelukast is currently only approved for this group in Germany [45].

The use of oral AHs and topical GCs as a combination in the treatment of AR has increased significantly in recent years. These combinations show pharmacological effects, but these occur with a slight delay and are not recommended [46, 47]. Evidence of better efficacy and, above all, safety of two combined drugs compared to the individual drugs is rare and can only be found for some free combinations [46]. In June 2018, Seresirikachorn et al. [46] published a review of randomized controlled trials in which the effect of different AHs in combination with intranasal GCs in AR patients was compared with the effect of intranasal GCs alone. The result of the meta-analysis showed that the effect of the combination of intranasal AHs with intranasal GCs on nasal and ocular symptoms is superior to the efficacy of monotherapy with intranasal GCs. The combination of oral AHs with intranasal GCs could not be recommended [46]. Feng et al. [48] came to similar conclusions [48].

2008, Ratner et al. compared a free combination of intranasal (IN) fluticasone and intranasal (IN) azelastine with the monoproducts and were able to show a significant superiority of the combination [49]. However, azelastine was used here in a dosage not approved in Germany. Two years later, Hampel et al. conducted a proof-of-concept study with commercially available IN azelastine and IN fluticasone as combination therapy. Here, a clinically significant superiority of the combination therapy over the monotherapies could be shown [50]. These and other studies resulted in the fixed combination MP29-02 [50,51,52].

Portmann et al. examined the acceptance of a free combination of azelastine and beclomethasone as early as 2000. Acceptance of the combination therapy was determined by means of a questionnaire, adherence to the protocol, and adherence to medication intake. The acceptance of the combination therapy was rated as good. However, there was no comparison between the combination therapy and the respective monotherapies, so that a superior efficacy of the combination therapy could not be proven [53].

Overall, studies show that about 40% of patients use a combination therapy with different preparations [39, 40], although the additional benefit of a second preparation could not be proven in many studies [54,55,56]. There are very few efficacy and safety studies of free combinations of different medications or groups of medications for the treatment of AR. While evidence-based studies have compared the efficacy of fixed combinations of AHs and GCs with monopreparations and corresponding safety analyses have been conducted, the safety and efficacy of free combinations of different preparations cannot be proven. In addition, when using a free combination of two intranasal preparations, it should be taken into account that the nasal mucosa has only a limited capacity to absorb liquids or substances contained therein [57]. When different nasal sprays are used, they should therefore be applied at a time interval from one another so that the different active substances can be absorbed at all via the nasal mucosa. In addition, when using intranasal AHs and GCs in free combination, the AH nasal spray should be administered before the GC nasal spray [49]. GCs are wrapped in a lipophilic membrane to ensure good absorption via the epithelial barrier, whereas AHs are hydrophilic and are therefore administered in an aqueous solution, which is why the carrier substances of the nasal sprays differ considerably [58, 59]. GC nasal sprays thus form a fine lipid film on the nasal mucosa, which can prevent the hydrophilic AH nasal spray from penetrating the mucosal barrier if it is applied administered after the GC nasal spray.

Fixed combination of topical glucocorticoid and intranasal antihistamine

In the therapy of bronchial asthma in adults, the inhaled fixed combination of a long-acting β mimetic with an inhaled GC is the treatment of choice from level 3 [60].

In AR, a fixed combination of an intranasal GC (fluticasone propionate) and an intranasal antihistamine (azelastine) with improved pharmacological properties has also been shown to be more effective in relieving symptoms than the administration of the individual drugs [50, 52, 61]. It has also been shown that the total cost of drugs and the use of the health care system can be reduced by the treatment with a fixed combination, compared to the therapy with the individual active ingredients [62].

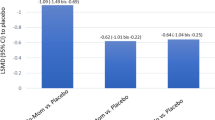

This fixed combination is based on the initial study by Ratner et al. who used two different nasal sprays of azelastine and fluticasone propionate [49]. Meltzer et al. were able to show that treatment with MP29-02 led to a 39% better reduction of overall nasal symptoms compared to treatment with fluticasone propionate [52]. MP29-02 had a significantly better effect on individual symptoms, particularly nasal obstruction, than the individual monotherapies [52]. For the other individual symptoms (nasal obstruction, pruritus, rhinorrhea and sneezing), MP29-02 proved to be superior to the monotherapies even in patients with severe AR [52].

According to the meta-analysis by Carr et al., the improvement of symptoms also occurred earlier than with therapy with the individual drugs (up to five days earlier than with fluticasone propionate and up to seven days earlier than with azelastine) [51, 61]. In addition, the treatment with MP29-02 resulted in a more complete improvement, so that a complete/almost complete reduction of symptoms was observed in one out of eight patients [51]. With an onset of action in only five minutes, this fixed combination is suitable for rapid and effective AR therapy compared to loose combination therapy; a significant reduction in symptoms occurs more than two hours earlier than with loratadine and an intranasal GC. The side effect profile, on the other hand, did not differ significantly from that of the monopreparations [52]. Today, fixed combinations are considered to be the most effective form of AR therapy and the standard therapy for severe forms of AR [51], since in addition to the better efficacy, drug compliance can generally be increased by using fixed combinations [63].

Another fixed combination of mometasone and olopatadine (GSP301) is currently being tested in clinical trials. First results show a significant reduction of AR symptoms compared to placebo in a double-blind pollen chamber study [64]. Studies on the pharmacokinetics of GSP301 have already shown that the fixed combination of olopatadine and mometasone is at least as readily available in a fixed combination as the mono products [65, 66].

Treatment with anti-IgE antibodies

In Germany omalizumab, a monoclonal antibody against IgE, is approved under the trade name Xolair® (Novartis Pharma GmbH, Nürnberg, Germany) for the treatment of severe bronchial asthma from the age of six years and chronic spontaneous urticaria. By now the efficacy of this form of treatment has been very well documented [67, 68]. Against the background of pathophysiological knowledge of the key role of IgE in the allergic inflammation cascade, omalizumab seems to be a therapy supplement worth considering in the treatment of AR, especially in combination with allergen immunotherapy (AIT) [69,70,71]. Although omalizumab is currently not approved for the treatment of AR, a combination of omalizumab with all the pharmacotherapies described above would be conceivable.

Discussion

Health care-relevant evaluation of drugs for the treatment of allergic rhinitis

Of the above-mentioned medications, decongestants (α sympathomimetics), mast cell stabilizers, many AHs and also several intranasal GCs are not subject to prescription (OTC) and therefore, according to Annex I of the Medical Drug Directive (AMR), can generally not be prescribed by the statutory health insurance (SHI).

Although the use of intranasal GCs is considered internationally as a guideline-based therapeutic standard for intermittent and persistent AR nowadays, there is only limited prescribability and reimbursement for this group of preparations for patients with SHI in Germany. The costs for these nonprescription preparations are therefore usually borne by the insured themselves, since according to §34, subparagraph 1, sentence 1 of the German Social Code, Book V, nonprescription drugs are excluded from medical care according to §31 SGB V.

As exceptions, the Federal Joint Committee (Gemeinsamer Bundesausschuss, G‑BA), in accordance with §34, subsection 1, sentence 2, SGB V, has specified in the guidelines pursuant to §92, subsection 1, sentence 2, No. 6, SGB V, which nonprescription drugs, which are considered to be the standard of therapy in the treatment of serious illnesses, can be exceptionally prescribed by the SHI-accredited physician for use in these illnesses. The serious illnesses for which, in special cases, nonprescription AHs can also be prescribed on a SHI prescription are defined according to the OTC exception list in Annex I of the Drug Directive.

As shown above, intranasal GCs nowadays represent the therapy standard for inflammatory diseases of the nasal mucous membranes and are also a very good therapy option for AR. In August 2018, the Joint Federal Committee decided on exceptions for the prescribability of intranasal GCs at the expense of the SHI. According to these, the nonprescription intranasal GCs with the active substances beclometasone, fluticasone, and mometasone can now again be prescribed “for the treatment of persistent AR with severe symptoms” on a panel prescription because severe forms of AR, which due to the severity of the health disorder have a long-term, lasting adverse effect on the quality of life, are a serious illness within the meaning of the Drug Directive.

In defining when a serious form of AR is involved, the Federal Joint Committee followed the ARIA guideline in its main reasons for its decision. Such a condition may exist “if it is a persistent AR”, in which the symptoms occur “on at least 4 days per week and over a period of at least 4 weeks” and must be classified as severe.

If there are no serious symptoms or if they last less than four weeks or less than four days per week, patients must continue to pay for the preparations themselves.

How can a guideline-based therapy be guaranteed?

Only reliable medical findings guarantee adequate therapy management, which is particularly important for the further course of the disease, secondary diseases and comorbidities in untreated or inadequately treated AR. In order to treat patients effectively and sustainably, medical therapy adjustment and monitoring is essential. Only in this way can patients be informed about further treatment options such as allergen-specific immunotherapy.

What has so far been lacking for SHI patients in Germany is a regulation for patients in whom both AHs and intranasal GCs are not sufficiently effective as monotherapies. These patients usually use arbitrary free combinations of different preparations and preparation groups, whereas only for fixed combinations of AHs and intranasal GKs an increase of the therapeutic effectiveness and thus a suitability for this patient group has been proven on an evidence-based basis.

Currently, there are only a few studies on the free combination of drugs for the treatment of AR. For the free combination of oral AHs and LT receptor antagonists, superior efficacy and safety compared to the mono preparations could only be demonstrated in AR patients with comorbid bronchial asthma [16, 41, 43, 44]. An improved efficacy or safety of other free combinations of preparation groups could not be demonstrated.

There are currently no generics for fixed combinations in Germany, and there is no possibility of OTC application, as these have not been released from prescription. This should consequently also enable SHI-accredited physicians to provide fully reimbursable and effective treatment of the most severe forms of AR with a reduction in quality of life, which means that therapy can continue to be provided under medical supervision.

A delimitation of free and arbitrary combinations of active substances by the Federal Joint Committee, the Associations of Statutory Health Insurance Physicians and review boards in the SHI regions, taking into account the current study situation and against the background of optimal physician-controlled care of patients with AR, would be desirable, since these patients do not have reliable evidence in controlled studies. Therefore, instead of recommending untested and arbitrary combinations, physicians who prescribe a guideline-based and evidence-based therapy with a fixed combination should not be threatened by drug recourse, since this guideline- and evidence-based therapy is the most effective symptomatic therapy, especially for patients with the most severe forms of AR [47, 72,73,74].

Abbreviations

- AH:

-

Antihistamine

- AIT:

-

Allergen-specific immunotherapy

- AMR:

-

Medical Drug Directive

- AR:

-

Allergic rhinitis

- ARIA:

-

Allergic rhinitis and its impact on asthma

- CDSS:

-

Clinical decision support system

- CysLT:

-

Cysteine leukotriene

- G‑BA:

-

Joint Federal Committee

- GCs:

-

Glucocorticoids

- GR:

-

Glucocorticoid receptor

- IN:

-

Intranasal

- LABA:

-

Long-acting beta-agonists

- LT:

-

Leukotriene

- MASK:

-

MACVIA-ARIA Sentinel Network

- NSS:

-

Nasal symptom score

- OTC:

-

Over the counter

- SGB:

-

German Social Security Code

- SHI:

-

Statutory Health Insurance

- TNSS:

-

Total nasal symptom score

- WHO:

-

World Health Organization

References

Brozek JL, Bousquet J, Baena-Cagnani CE, Bonini S, Canonica GW, Casale TB, et al. Allergic Rhinitis and its Impact on Asthma (ARIA) guidelines: 2010 revision. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2010;126:466–76.

Marple BF, Fornadley JA, Patel AA, Fineman SM, Fromer L, Krouse JH, et al. Keys to successful management of patients with allergic rhinitis: focus on patient confidence, compliance, and satisfaction. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2007;136(6 Suppl):S107–S24.

Khan MA, Abou-Halawa AS, Al-Robaee AA, Alzolibani AA, Al-Shobaili HA. Daily versus self-adjusted dosing of topical mometasone furoate nasal spray in patients with allergic rhinitis: randomised, controlled trial. J Laryngol Otol. 2010;124:397–401.

Bousquet J, Arnavielhe S, Bedbrook A, Bewick M, Laune D, Mathieu-Dupas E, et al. MASK study group. MASK 2017: ARIA digitally-enabled, integrated, person-centred care for rhinitis and asthma multimorbidity using real-world-evidence. Clin Transl Allergy. 2018;8:45.

Brożek JL, Bousquet J, Agache I, Agarwal A, Bachert C, Bosnic-Anticevich S, et al. Allergic Rhinitis and its Impact on Asthma (ARIA) guidelines-2016 revision. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2017;140:950–8.

Bousquet J, Pfaar O, Togias A, Schünemann HJ, Ansotegui I, Papadopoulos NG, et al. Positionspapier. ARIA-Versorgungspfade für die Allergenimmuntherapie. Allergologie. 2019;42(09):404–25.

Blaiss MS. Important aspects in management of allergic rhinitis: compliance, cost, and quality of life. Allergy Asthma Proc. 2003;24:231–8.

Meltzer EO. An overview of current pharmacotherapy in perennial rhinitis. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 1995;95(5 Pt 2):1097–110.

Price D, Scadding G, Ryan D, Bachert C, Canonica GW, Mullol J, et al. The hidden burden of adult allergic rhinitis: UK healthcare resource utilisation survey. Clin Transl Allergy. 2015;5:39.

Hellings PW, Fokkens WJ, Akdis C, Bachert C, Cingi C, Dietz de Loos D, et al. Uncontrolled allergic rhinitis and chronic rhinosinusitis: where do we stand today? Allergy. 2013;68:1–7.

Bousquet J, Schunemann HJ, Fonseca J, Samolinski B, Bachert C, Canonica GW, et al. MACVIA-ARIA Sentinel NetworK for allergic rhinitis (MASK-rhinitis): the new generation guideline implementation. Allergy. 2015;70:1372–92.

Bousquet J, Schünemann HJ, Hellings PW, Arnavielhe S, Bachert C, Bedbrook A, et al. MACVIA clinical decision algorithm in adolescents and adults with allergic rhinitis. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2016;138:367–374.e2.

Interdisziplinäre Arbeitsgruppe „Allergische Rhinitis“ der Sektion HNO. Allergische Rhinokonjunktivitis – Leitlinie der Deutschen Gesellschaft für Allergologie und klinische Immunologie (DGAI). Allergo J. 2003;12:182–94.

Ratner PH, Ehrlich PM, Fineman SM, Meltzer EO, Skoner DP. Use of intranasal cromolyn sodium for allergic rhinitis. Mayo Clin Proc. 2002;77:350–4.

Samuelsson B. Leukotrienes: mediators of immediate hypersensitivity reactions and inflammation. Science. 1983;220:568–75.

Rodrigo GJ, Yañez A. The role of antileukotriene therapy in seasonal allergic rhinitis: a systematic review of randomized trials. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2006;96:779–86.

Lehtimäki L, Petäys T, Haahtela T. Montelukast is not effective in controlling allergic symptoms outside the airways: a randomised double-blind placebo-controlled crossover study. Int Arch Allergy Immunol. 2009;149:150–3.

Stokes JR, Romero FA Jr, Allan RJ, Phillips PG, Hackman F, Misfeldt J, et al. The effects of an H3 receptor antagonist (PF-03654746) with fexofenadine on reducing allergic rhinitis symptoms. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2012;129(12):409–412.e2.

Kay GG, Quig ME. Impact of sedating antihistamines on safety and productivity. Allergy Asthma Proc. 2001;22:281–3.

Newson-Smith G, Powell M, Baehre M, Garnham SP, MacMahon MT. A placebo controlled study comparing the efficacy of intranasal azelastine and beclomethasone in the treatment of seasonal allergic rhinitis. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 1997;254:236–41.

Mullol J, Bousquet J, Bachert C, Canonica WG, Gimenez-Arnau A, Kowalski ML, et al. Rupatadine in allergic rhinitis and chronic urticaria. Allergy. 2008;63(Suppl 87):5–28.

Thorn C, Pfaar O, Hörmann K, Klimek L. Rupatadin – Pharmakologie, klinische Wirksamkeit und therapeutische Sicherheit eines neuen Antihistamins mit zusätzlicher, PAF-antagonisierender Wirkung. AL. 2010;33:429–40.

Perez I, Villa M, De La Cruz G. Rupatadine in allergic rhinitis: Pooled analysis of efficacy data. Allergy. 2002;57:245.

Yamamoto H, Yamada T, Kubo S, Osawa Y, Kimura Y, Oh M, et al. Efficacy of oral olopatadine hydrochloride for the treatment of seasonal allergic rhinitis: A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. Allergy Asthma Proc. 2010;31:296–303.

Sádaba Díaz de Rada B, Azanza Perea JR, Gomez-Guiu Hormigos A. Bilastine for the relief of allergy symptoms. Drugs Today (Barc). 2011;47:251–62.

Kuna P, Bachert C, Nowacki Z, van Cauwenberge P, Agache I, Fouquert L, et al. Efficacy and safety of bilastine 20 mg compared with cetirizine 10 mg and placebo for the symptomatic treatment of seasonal allergic rhinitis: a randomized, double-blind, parallel-group study. Clin Exp Allergy. 2009;39:1338–47.

Zuberbier T, Oanta A, Bogacka E, Medina I, Wesel F, Uhl P, et al. Comparison of the efficacy and safety of bilastine 20 mg vs levocetirizine 5 mg for the treatment of chronic idiopathic urticaria: a multi-centre, double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled study. Allergy. 2010;65:516–28.

Bachert C, Kuna P, Sanquer F, Ivan P, Dimitrov V, Gorina MM, et al. Comparison of the efficacy and safety of bilastine 20 mg vs desloratadine 5 mg in seasonal allergic rhinitis patients. Allergy. 2009;64:158–65.

Yañez A, Rodrigo GJ. Intranasal corticosteroids versus topical H1 receptor antagonists for the treatment of allergic rhinitis: a systematic review with meta-analysis. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2002;89:479–84.

Kaliner MA, Berger WE, Ratner PH, Siegel CJ. The efficacy of intranasal antihistamines in the treatment of allergic rhinitis. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2011;106(2 Suppl):S6–S11.

Okano M. Mechanisms and clinical implications of glucocorticosteroids in the treatment of allergic rhinitis. Clin Exp Immunol. 2009;158:164–73.

Klimek L, Högger P, Pfaar O. Wirkmechanismen nasaler Glukokortikosteroide in der Therapie der allergischen Rhinitis. Teil 1: Pathophysiologie, molekulare Grundlagen. [Mechanism of action of nasal glucocorticosteroids in the treatment of allergic rhinitis. Part 1: Pathophysiology, molecular basis]. HNO. 2012;60:611–7.

Skoner DP, Rachelefsky GS, Meltzer EO, Chervinsky P, Morris RM, Seltzer JM, et al. Detection of growth suppression in children during treatment with intranasal beclomethasone dipropionate. Pediatrics. 2000;105:E23.

Bernstein JA. Evaluating the effectiveness of medications in the treatment of allergic rhinitis. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2010;105:189. author reply 189.

Benninger M, Farrar JR, Blaiss M, Chipps B, Ferguson B, Krouse J, et al. Evaluating approved medications to treat allergic rhinitis in the United States: an evidence-based review of efficacy for nasal symptoms by class. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2010;104:13–29.

Bousquet J, Pfaar O, Togias A, Schünemann HJ, Ansotegui I, Papadopoulos NG, et al. 2019 ARIA care pathways for allergen immunotherapy. Allergy. 2019;74:2087–102.

Bédard A, Basagaña X, Anto JM, Garcia-Aymerich J, Devillier P, Arnavielhe S, et al. MASK study group. Mobile technology offers novel insights into the control and treatment of allergic rhinitis: The MASK study. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2019;144:135–143.e6.

Bousquet J, Devillier P, Arnavielhe S, Bedbrook A, Alexis-Alexandre G, van Eerd M, et al. Treatment of allergic rhinitis using mobile technology with real-world data: The MASK observational pilot study. Allergy. 2018;73:1763–74.

Canonica GW, Bousquet J, Mullol J, Scadding GK, Virchow JC. A survey of the burden of allergic rhinitis in Europe. Allergy. 2007;62(Suppl 85):17–25.

Dalal AA, Stanford R, Henry H, Borah B. Economic burden of rhinitis in managed care: a retrospective claims data analysis. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2008;101:23–9.

Day JH, Briscoe MP, Ratz JD, Danzig M, Yao R. Efficacy of loratadine-montelukast on nasal congestion in patients with seasonal allergic rhinitis in an environmental exposure unit. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2009;102:328–38.

Meltzer EO, Malmstrom K, Lu S, Prenner BM, Wei LX, Weinstein SF, et al. Concomitant montelukast and loratadine as treatment for seasonal allergic rhinitis: a randomized, placebo-controlled clinical trial. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2000;105:917–22.

Prenner P, Anolik R, Danzig M, Yao R. Efficacy and safety of fixed-dose loratadine/montelukast in seasonal allergic rhinitis: effects on nasal congestion. Allergy Asthma Proc. 2009;30:263–9.

Cingi C, Gunhan K, Gage-White L, Unlu H. Efficacy of leukotriene antagonists as concomitant therapy in allergic rhinitis. Laryngoscope. 2010;120:1718–23.

MSD. SINGULAIR® – Fachinformation (Zusammenfassung der Merkmale der Arzneimittel). MSD Sharp & Dohme GmbH. 2019. https://www.msd.de/fileadmin/files/fachinformationen/singulair.pdf, Rote Liste Service GmbH, https://www.patienteninfo-service.de/a-z-liste/s/. Accessed: 10.06.2020.

Seresirikachorn K, Chitsuthipakorn W, Kanjanawasee D, Khattiyawittayakun L, Snidvongs K. Effects of H1 antihistamine addition to intranasal corticosteroid for allergic rhinitis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int Forum Allergy Rhinol. 2018;8:1083–92.

Bousquet J, Meltzer EO, Couroux P, Koltun A, Kopietz F, Munzel U, et al. Onset of action of the fixed combination intranasal azelastine-fluticasone propionate in an allergen exposure chamber. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2018;6:1726–1732.e6.

Feng S, Fan Y, Liang Z, Ma R, Cao W. Concomitant corticosteroid nasal spray plus antihistamine (oral or local spray) for the symptomatic management of allergic rhinitis. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2016;273:3477–86.

Ratner PH, Hampel F, Van Bavel J, Amar NJ, Daftary P, Wheeler W, et al. Combination therapy with azelastine hydrochloride nasal spray and fluticasone propionate nasal spray in the treatment of patients with seasonal allergic rhinitis. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2008;100:74–81.

Hampel FC, Ratner PH, Van Bavel J, Amar NJ, Daftary P, Wheeler W, et al. Double-blind, placebo-controlled study of azelastine and fluticasone in a single nasal spray delivery device. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2010;105:168–73.

Leung DYM, Szefler J. The editors’ choice. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2012;129:1216–7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaci.2012.03.019.

Meltzer EO, LaForce C, Ratner P, Price D, Ginsberg D, Carr W. MP29-02 (a novel intranasal formulation of azelastine hydrochloride and fluticasone propionate) in the treatment of seasonal allergic rhinitis: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of efficacy and safety. Allergy Asthma Proc. 2012;33:324–32.

Portmann D, Le Gal M, Jessent V, Verrière JL. Acceptability of local treatment of allergic rhinitis with a combination of a corticoid (beclomethasone) and an antihistaminic (azelastine). Rev Laryngol Otol Rhinol (Bord). 2000;121:273–9.

Anolik R. Clinical benefits of combination treatment with mometasone furoate nasal spray and loratadine vs monotherapy with mometasone furoate in the treatment of seasonal allergic rhinitis. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2008;100:264–71.

Di Lorenzo G, Pacor ML, Pellitteri ME, Morici G, Di Gregoli A, Lo Bianco C, et al. Randomized placebo-controlled trial comparing fluticasone aqueous nasal spray in mono-therapy, fluticasone plus cetirizine, fluticasone plus montelukast and cetirizine plus montelukast for seasonal allergic rhinitis. Clin Exp Allergy. 2004;34:259–67.

van Galen KA, Nellen JF, Nieuwkerk PT. The effect on treatment adherence of administering drugs as fixed-dose combinations versus as separate pills: systematic review and meta-analysis. Aids Res Treat. 2014;2014:967073.

D’Addio AD, Ruiz NM, Mayer MJ, Berger W, Meltzer EO. Quantification of the distribution of MP29-02 (Dymista-Azelastine HCl/Fluticasone propionate nasal spray) in an anatomical model of the human nasal cavity. Poster session. AAAAI annual meeting 2015, Houston, Texas.. https://www.eposters.net/pdfs/quantification-of-the-distribution-of-mp29-02-dymista-azelastine-hclfluticasone-propionate-nasal.pdf. Accessed:: 10.06.2020.

Bernstein JA. Azelastine hydrochloride: a review of pharmacology, pharmacokinetics, clinical efficacy and tolerability. Curr Med Res Opin. 2007;23:2441–52.

Shaw RJ. Pharmacology of fluticasone propionate. Respir Med. 1994;88(Suppl A):5–8.

Pfaar O, Bachert C, Bufe A, Buhl R, Ebner C, Eng P, et al. Guideline on allergen-specific immunotherapy in IgE-mediated allergic diseases: S2k Guideline of the German Society for Allergology and Clinical Immunology (DGAKI), the Society for Pediatric Allergy and Environmental Medicine (GPA), the Medical Association of German Allergologists (AeDA), the Austrian Society for Allergy and Immunology (ÖGAI), the Swiss Society for Allergy and Immunology (SGAI), the German Society of Dermatology (DDG), the German Society of Oto- Rhino-Laryngology, Head and Neck Surgery (DGHNO-KHC), the German Society of Pediatrics and Adolescent Medicine (DGKJ), the Society for Pediatric Pneumology (GPP), the German Respiratory Society (DGP), the German Association of ENT Surgeons (BV-HNO), the Professional Federation of Paediatricians and Youth Doctors (BVKJ), the Federal Association of Pulmonologists (BDP) and the German Dermatologists Association (BVDD). Allergo J Int. 2014;23:282–319.

Carr W, Bernstein J, Lieberman P, Meltzer E, Bachert C, Price D, et al. A novel intranasal therapy of azelastine with fluticasone for the treatment of allergic rhinitis. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2012;129:1282–1289.e1.

Harrow B, Sedaghat AR, Caldwell-Tarr A, Dufour R. A comparison of health care resource utilization and costs for patients with allergic rhinitis on single-product or free-combination therapy of intranasal steroids and Intranasal antihistamines. J Manag Care Spec Pharm. 2016;22:1426–36.

Bangalore S, Kamalakkannan G, Parkar S, Messerli FH. Fixed-dose combinations improve medication compliance: a meta-analysis. Am J Med. 2007;120:713–9.

Patel P, Salapatek AM, Tantry SK. Effect of olopatadine-mometasone combination nasal spray on seasonal allergic rhinitis symptoms in an environmental exposure chamber study. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2019;122:160–166.e1.

Patel P, Salapatek AM, Talluri RS, Tantry SK. Pharmacokinetics of intranasal olopatadine in the fixed-dose combination GSP301 versus two monotherapy intranasal olopatadine formulations. Allergy Asthma Proc. 2018;39:224–31.

Patel P, Salapatek AM, Talluri RS, Tantry SK. Pharmacokinetics of intranasal mometasone in the fixed-dose combination GSP301 versus two monotherapy intranasal mometasone formulations. Allergy Asthma Proc. 2018;39:232–9.

Ledford DK. Omalizumab: overview of pharmacology and efficacy in asthma. Expert Opin Biol Ther. 2009;9:933–43.

Niven R, Chung KF, Panahloo Z, Blogg M, Ayre G. Effectiveness of omalizumab in patients with inadequately controlled severe persistent allergic asthma: an open-label study. Respir Med. 2008;102:1371–8.

Kamin W, Kopp MV, Erdnuess F, Schauer U, Zielen S, Wahn U. Safety of anti-IgE treatment with omalizumab in children with seasonal allergic rhinitis undergoing specific immunotherapy simultaneously. Pediatr Allergy Immunol. 2010;21(1 Pt 2):e160–e5.

Kopp MV, Hamelmann E, Zielen S, Kamin W, Bergmann KC, Sieder C, et al. Combination of omalizumab and specific immunotherapy is superior to immunotherapy in patients with seasonal allergic rhinoconjunctivitis and co-morbid seasonal allergic asthma. Clin Exp Allergy. 2009;39:271–9.

Stock P, Rolinck-Werninghaus C, Wahn U, Hamelmann E. The role of anti-IgE therapy in combination with allergen specific immunotherapy for seasonal allergic rhinitis. BioDrugs. 2007;21:403–10.

Berger W, Bousquet J, Fox AT, Just J, Muraro A, Nieto A, et al. MP-AzeFlu is more effective than fluticasone propionate for the treatment of allergic rhinitis in children. Allergy. 2016;71:1219–22.

Haahr PA, Jacobsen C, Christensen ME. MP-AzeFlu provides rapid and effective allergic rhinitis control: results of a non-interventional study in Denmark. Int Forum Allergy Rhinol. 2019;9:388–95.

Kortekaas Krohn I, Callebaut I, Alpizar YA, Steelant B, Van Gerven L, Skov PS, et al. MP29-02 reduces nasal hyperreactivity and nasal mediators in patients with house dust mite-allergic rhinitis. Allergy. 2018;73:1084–93.

Funding

Open Access funding provided by Projekt DEAL.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

S. Becker received grants, fees and non-financial support from Ambu, ALK-Abelló, Allergopharma, Bencard Allergie GmbH, Bristol-Myers Squibb, HAL Allergie and Sanofi Genzyme, outside of the present work. T. Biedermann received grants and/or fees from Alk-Abelló, Astellas, Bencard, Biogen, Janssen, Leo, Meda, MSD, Novartis, Phadia and Thermo Fisher, outside of this work. Outside of this work, J. Bousquet received fees from and worked as an adviser (advisory board member, lectures) for Chiesi, Cipla, Hikma, Menarini, Mundipharma, Mylan, Novartis, Sanofi-Aventis, Takeda, Teva, Uriach and Kyomed. L Klimek received grants and/or fees from Allergopharma, Meda/Mylan, HAL Allergy, ALK-Abelló, Leti Pharma, Allergy Therapeutics, Stallergenes, Quintiles, Sanofi, AstraZeneca, GSK, ASIT Biotech and Lofarma, outside of this work. L. Klimek is also President of the AeDA and a member of the following companies: DGHNO, DGAKI, GPA and EAACI. R. Mösges received fees and/or grants and/or non-financial support from ALK-Abelló, ASIT Biotech, Allergopharma, Allergy Therapeutics, Bencard, Leti Pharma, Lofarma, Roxall, Stallergenes, Optima, Friulchem, Hexal, Servier, Klosterfrau, Atmos, Bayer, Bionorica, FAES, GSK, MSD, Johnson & Johnson, Meda, Novartis, Otonomy, Stada, UCB, Ferrero, BitopAG, Hulka, Nuvo and Ursapharm, outside of this work. H. Olze is a member of the Advisory Board at Meda Pharma. O. Pfaar received grants and/or fees from ALK-Abelló, Allergopharma, Stallergenes Greer, HAL Allergy Holding/HAL Allergie, Bencard Allergie/Allergy Therapeutics, Lofarma, Biomay, Circassia, ASIT Biotech Tools, Laboratorios Leti/Leti Pharma, Meda Pharma/Mylan, Anergis, Mobile Chamber Experts (a GA2LEN partner), Indoor Biotechnologies, GSK, Astellas Pharma Global, Euforea, Roxall, Novartis and Sanofi Aventis, outside of this work. J. Ring received fees from Mylan, Allergics, Galderma, Sanofi-Genzyme, ThermoFisher and Leo Pharma, outside of the present work. T. Zuberbier received fees (for example for lectures, advice, expert opinions) from Bayer Health Care, FAES, Novartis, Henkel, Novartis, Henkel, AstraZeneca, Abbvie, ALK, Almirall, Astellas, Bayer Health Care, Bencard, Berlin Chemie, FAES, HAL, Leti, Meda, Menarini, Merck MSD, Novartis, Pfizer, Sanofi, Stallergenes, Takeda, Teva, UCB, Henkel, Kryolan and L’Oréal, outside of this work. I. Casper, K.-C. Bergmann, P. Hellings, K. Jung, H. Merk, W. Schlenter, M. Gröger, A. Chaker and W. Wehrmann declare that there are no conflicts of interest.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Klimek, L., Casper, I., Bergmann, KC. et al. Therapy of allergic rhinitis in routine care: evidence-based benefit assessment of freely combined use of various active ingredients. Allergo J Int 29, 129–138 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40629-020-00133-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40629-020-00133-7