Abstract

Background

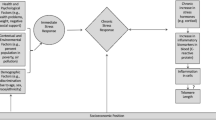

African American men in the USA experience poorer aging-related health outcomes compared to their White counterparts, partially due to socioeconomic disparities along racial lines. Greater exposure to socioeconomic strains among African American men may adversely impact health and aging at the cellular level, as indexed by shorter leukocyte telomere length (LTL). This study examined associations between socioeconomic factors and LTL among African American men in midlife, a life course stage when heterogeneity in both health and socioeconomic status are particularly pronounced.

Methods

Using multinomial logistic regression, we examined associations between multiple measures of SES and tertiles of LTL in a sample of 92 African American men between 30 to 50 years of age.

Results

Reports of greater financial strain were associated with higher odds of short versus medium LTL (odds ratio (OR)=2.21, p = 0.03). Higher income was associated with lower odds of short versus medium telomeres (OR=0.97, p = 0.04). Exploratory analyses revealed a significant interaction between educational attainment and employment status (χ 2 = 4.07, p = 0.04), with greater education associated with lower odds of short versus long telomeres only among those not employed (OR=0.10, p = 0.040).

Conclusion

Cellular aging associated with multiple dimensions of socioeconomic adversity may contribute to poor aging-related health outcomes among African American men. Subjective appraisal of financial difficulty may impact LTL independently of objective dimensions of SES. Self-appraised success in fulfilling traditionally masculine gender roles, including being an economic provider, may be a particularly salient aspect of identity for African American men and have implications for cellular aging in this population.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Marmot MG, Shipley MJ, Rose G. Inequalities in death—specific explanations of a general pattern? Lancet. 1984;1:1003–6.

Clarke CA, Miller T, Chang ET, Yin D, Cockburn M, Gomez SL. Racial and social class gradients in life expectancy in contemporary California. Soc Sci Med. 2010;70:1373–80.

Fiscella K, Tancredi D. Socioeconomic status and coronary heart disease risk prediction. JAMA. 2008;300:2666–8.

Franks P, Gold MR, Fiscella K. Sociodemographics, self-rated health, and mortality in the US. Soc Sci Med. 2003;56:2505–14.

Lorant V, Deliege D, Eaton W, Robert A, Philippot P, Ansseau M. Socioeconomic inequalities in depression: a meta-analysis. Am J Epidemiol. 2003;157:98–112.

Adler NE, Stewart J. Health disparities across the lifespan: meaning, methods, and mechanisms. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2010;1186:5–23.

Do DP, Frank R, Finch BK. Does SES explain more of the black/white health gap than we thought? Revisiting our approach toward understanding racial disparities in health. Soc Sci Med. 2012;74:1385–93.

Farmer MM, Ferraro KF. 2005. Are racial disparities in health conditional on socioeconomic status? Soc Sci Med. 2005;60:191–204.

Ostrove JM, Feldman P, Adler NE. Relations among socioeconomic status indicators and health for African-Americans and whites. J Health Psychol. 1999;4:451–63.

Sweet E, McDade TW, Kiefe CI, Liu K. Relationships between skin color, income, and blood pressure among African Americans in the CARDIA study. Am J Public Health. 2007;97:2253–9.

Gruenewald TL, Cohen S, Matthews KA, Tracy R, Seeman TE. Association of socioeconomic status with inflammation markers in black and white men and women in the Coronary Artery Risk Development in Young Adults (CARDIA) Study. Soc Sci Med. 2009;69:451–9.

Sims M, Diez Roux AV, Boykin S, Sarpong D, Gebreab SY, Wyatt SB, et al. The socioeconomic gradient of diabetes prevalence, awareness, treatment, and control among African Americans in the Jackson Heart Study. Ann Epidemiol. 2011;21:892–8.

Yaffe K, Falvey C, Harris TB, Newman A, Satterfield S, Koster A, et al. Effect of socioeconomic disparities on incidence of dementia among biracial older adults: prospective study. BMJ. 2013;347:f7051.

Winkleby MA, Cubbin C. Influence of individual and neighbourhood socioeconomic status on mortality among Black, Mexican-American, and White women and men in the United States. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2003;57:444–52.

Griffith DM. An intersectional approach to men’s health. Am J Mens Health. 2012;9:106–12.

Hammond WP, Mattis JS. Being a man about it: manhood meaning among African American men. Psychol Men Masculin. 2005;6:114–26.

Mendez DD, Hogan VK, Culhane J. Institutional racism and pregnancy health: using Home Mortgage Disclosure Act data to develop an index for mortgage discrimination at the community level. Public Health Rep. 2011;126:102–14.

Pager D, Shepherd H. The sociology of discrimination: racial discrimination in employment, housing, credit, and consumer markets. Annu Rev Sociol. 2008;34:181–209.

Stolzenberg L, D'Alessio SJ, Eitle D. Race and cumulative discrimination in the prosecution of criminal defendants. Race Justice. 2013;3:275–99.

Isaacs J, Sawhill I, Haskins R. Getting ahead or losing ground: economic mobility in America. Washington, DC: Brookings Institution; 2007.

Griffith DM, Ellis KR, Allen JO. An intersectional approach to social determinants of stress for African American men: men’s and women’s perspectives. Am J Mens Health. 2013;7:19S–30S.

Watkins DC, Walker RL, Griffith DM. A meta-study of Black male mental health and well-being. J Black Psychol. 2010;36:303–30.

Williams DR. The health of men: structured inequalities and opportunities. Am J Public Health. 2003;93:724–31.

Gilbert KL, Ray R, Siddiqi A, Shetty S, Baker EA, Elder K, et al. Visible and invisible trends in Black men's health: pitfalls and promises for addressing racial, ethnic, and gender inequities in health. Annu Rev Public Health. 2016;37:295–311.

Khan JR, Pearlin LI. Financial strain over the life course and health among older adults. J Health Soc Behav. 2006;47:17–31.

Shippee TP, Wilkinson LR, Ferraro KF. Accumulated financial strain and women’s health over three decades. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. 2012;67:585–94.

Szanton SL, Allen JK, Thorpe RJ Jr, Seeman T, Bandeen-Roche K, Fried LP. Effect of financial strain on mortality in community-dwelling older women. The J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. 2008;63:S369–74.

Szanton SL, Thorpe RJ, Whitfield K. Life-course financial strain and health in African-Americans. Soc Sci Med. 2010;71:259–65.

Puterman E, Adler NE, Matthews KA, Epel E. Financial strain and impaired fasting glucose: the moderating role of physical activity in the Coronary Artery Risk Development in Young Adults Study. Psychosom Med. 2012;74:187–92.

McEwen BS, Gianaros PJ. Central role of the brain in stress and adaptation: links to socioeconomic status, health, and disease. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2010;1186:190–222.

Finkel T, Holbrook NJ. Oxidants, oxidative stress and the biology of ageing. Nature. 2000;408:239–47.

Willeit P, Willeit J, Brandstätter A, Ehrlenbach S, Mayr A, Gasperi A, et al. Cellular aging reflected by leukocyte telomere length predicts advanced atherosclerosis and cardiovascular disease risk. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2010;30:1649–56.

Boonekamp JJ, Simons MJP, Hemerik L, Verhulst S. Telomere length behaves as a biomarker of somatic redundancy rather than biological age. Aging Cell. 2013;12:330–2.

Grodstein F, van Oijen M, Irizarry MC, Rosas HD, Hyman BT, Growdon JH, et al. Shorter telomeres may mark early risk of dementia: preliminary analysis of 62 participants from the Nurses’ Health Study. PLoS One. 2008;3:e1590.

Aubert G, Lansdorp PM. Telomeres and aging. Physiol Rev. 2008;88:557–79.

Richter T, von Zglinicki T. A continuous correlation between oxidative stress and telomere shortening in fibroblasts. Exp Geront. 2007;42:1039–42.

O’Donovan A, Pantell MS, Puterman E, Dhabhar FS, Blackburn EH, Yaffe K, et al. Cumulative inflammatory load is associated with short leukocyte telomere length in the health. Aging and Body Composition Study PLoS One. 2011;6:19687.

Wolkowitz OM, Mellon SH, Epel ES, Lin J, Dhabhar FS, Su Y, et al. Leukocyte telomere length in major depression: correlations with chronicity, inflammation, and oxidative stress—preliminary findings. PLoS One. 2011;6:e17837.

Simon NM, Smoller JW, McNamara KL, Maser RS, Zalta AK, Pollack MH, et al. Telomere shortening and mood disorders: preliminary support for a chronic stress model of accelerated aging. Biol Psychiatry. 2006;60:432–5.

Damjanovic AK, Yang Y, Glaser R, Kiecolt-Glaser JK, Nguyen H, Laskowski B, et al. Accelerated telomere erosion is associated with a declining immune function of caregivers of Alzheimer’s disease patients. J Immunol. 2007;179:4249–54.

Kiecolt-Glaser JK, Gouin J, Weng N, Malarkey WB, Beversdorf DQ, Glaser R. Childhood adversity heightens the impact of later-life caregiving stress on telomere length and inflammation. Psychosom Med. 2011;73:16–22.

Shiels PG, McGlynn LM, MacIntyre A, Johnson PC, Batty GD, Burns H, et al. Accelerated telomere attrition is associated with relative household income, diet and inflammation in the pSoBid cohort. PLoS One. 2011;6:e22521.

Robertson T, Batty GD, Der G, Green MJ, McGlynn LM, McIntyre A, et al. Is telomere length socially patterned? Evidence from the West of Scotland Twenty-07 Study. PLoS One. 2012;7:e41805.

Adler NE, Pantell MS, O’Donovan A, Blackburn E, Cawthon R, Koster A, et al. Educational attainment and late life telomere length in the Health, Aging and Body Composition Study. Brain Behav Immun. 2013;27:15–21.

Carroll JE, Diez-Roux AV, Adler NE, Seeman TE. Socioeconomic factors and leukocyte telomere length in a multi-ethnic sample: findings from the Multi-ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis (MESA). Brain Behav Immun. 2013;28:108–14.

Needham BL, Adler N, Gregorich S, Rehkopf D, Lin J, Blackburn EH, et al. Socioeconomic status, health behavior, and leukocyte telomere length in the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, 1999-2002. Soc Sci Med. 2013;85:1–8.

Adams J, Martin-Ruiz C, Pearce M, White M, Parker L, von Zglinicki T. No association between socio-economic status and white blood cell telomere length. Aging Cell. 2007;6:125–8.

Batty GD, Wang Y, Brouilette SW, Shiels P, Packard C, Moore J, et al. Socioeconomic status and telomere length: the West of Scotland Coronary Prevention Study. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2009;63:839–41.

Chae DH, Nuru-Jeter AM, Adler NE. Implicit racial bias as a moderator between racial discrimination and hypertension: a study of midlife African American men. Psychosom Med. 2012;74:961–4.

Chae DH, Nuru-Jeter AM, Adler NE, Brody GH, Lin J, Blackburn EH, et al. Discrimination, racial bias, and telomere length in African-American men. Am J Prev Med. 2014;46:103–11.

McDade TW, Williams S, Snodgrass JJ. What a drop can do: dried blood spots as a minimally invasive method for integrating biomarkers into population-based research. Demography. 2007;44:899–925.

Cawthon RM. Telomere measurement by quantitative PCR. Nucleic Acids Res. 2002;30:e47.

Lin J, Epel E, Cheon J, Kroenke C, Sinclair E, Bigos M, et al. Analyses and comparisons of telomerase activity and telomere length in human T and B cells: insights for epidemiology of telomere maintenance. J Immunol Methods. 2010;352:71–80.

Yaffe K, Lindquist K, Kluse M, Cawthon R, Harris T, Hsueh WC, et al. Telomere length and cognitive function in community dwelling elders: findings from the Health ABC study. Neurobiol Aging. 2011;32:2055–60.

Geronimus AT, Pearson JA, Linnenbringer E, Schulz AJ, Reyes AG, Epel ES, et al. Race-ethnicity, poverty, urban stressors, and telomere length, in a Detroit community-based sample. J Health Soc Behav. 2015;56:199–224.

Litwin H, Sapir EV. Perceived income inadequacy in older adults in 12 countries: findings from the Survey of Health, Ageing and Retirement in Europe. Gerontologist. 2009;49:397–406.

Entringer S, Epel ES, Kumsta R, Lin J, Hellhammer DH, Blackburn EH, et al. Stress exposure in intrauterine life is associated with shorter telomere length in young adulthood. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011;108:e513–8.

Epel ES, Blackburn EH, Lin J, Dhabhar FS, Adler NE, Morrow JD, et al. Accelerated telomere shortening in response to life stress. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101:17312–5.

Drury SS, Theall K, Gleason MM, Smyke AT, De Vivo I, Wong JY, et al. Telomere length and early severe social deprivation: linking early adversity and cellular aging. Mol Psychiatry. 2012;17:719–27.

Ross CE, Mirowski J. The interaction of personal and parental education on health. Soc Sci Med. 2011;72:591–9.

Ross CE, Mirowski J. Sex differences in the effect of education on depression: resource multiplication or resource substitution? Soc Sci Med. 2006;63:1400–13.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the National Institute on Aging of the National Institutes of Health under Grants K01AG041787 to D.H.C. and P30 AG015281 to R.J.T.; the University of California, Berkeley Population Center; the University of California, San Francisco Health Disparities Group; and the Emory University Race and Difference Initiative. We thank the respondents of the Bay Area Heart Health Study for their participation.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Disclosure Statement

J.L. is a co-founder of Telomere Diagnostics Inc. and serves on its scientific advisory board. The company plays no role in the current study. No other financial disclosures were reported by the authors of this paper.

Ethical Approval

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Informed Consent

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Schrock, J.M., Adler, N.E., Epel, E.S. et al. Socioeconomic Status, Financial Strain, and Leukocyte Telomere Length in a Sample of African American Midlife Men. J. Racial and Ethnic Health Disparities 5, 459–467 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40615-017-0388-3

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40615-017-0388-3