Abstract

Injuries have a detrimental impact on team and individual athletic performance. Deficits in maximal strength, rate of force development (RFD), and reactive strength are commonly reported following several musculoskeletal injuries. This article first examines the available literature to identify common deficits in fundamental physical qualities following injury, specifically strength, rate of force development and reactive strength. Secondly, evidence-based strategies to target a resolution of these residual deficits will be discussed to reduce the risk of future injury. Examples to enhance practical application and training programmes have also been provided to show how these can be addressed.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Drew MK, Raysmith BP, Charlton PC. Injuries impair the chance of successful performance by sportspeople: a systematic review. Br J Sports Med. 2017;51(16):1209–14.

Hagglund M, et al. Injuries affect team performance negatively in professional football: an 11-year follow-up of the UEFA Champions League injury study. Br J Sports Med. 2013;47(12):738–42.

Williams S, et al. Time loss injuries compromise team success in Elite Rugby Union: a 7-year prospective study. Br J Sports Med. 2016;50(11):651.

Windt J, et al. Does player unavailability affect football teams’ match physical outputs? A two-season study of the UEFA champions league. J Sci Med Sport. 2018;21(5):525–32.

Esteve E, et al. Preseason adductor squeeze strength in 303 Spanish Male Soccer Athletes: a cross-sectional study. Orthop J Sports Med. 2018;6(1):2325967117747275.

Hägglund M, Waldén M, Ekstrand J. Risk factors for lower extremity muscle injury in professional soccer: the UEFA injury study. Am J Sports Med. 2012;41(2):327–35.

Arnason A, et al. Risk factors for injuries in football. Am J Sports Med. 2004;32(1 Suppl):5s–16s.

Hagglund M, Walden M, Ekstrand J. Previous injury as a risk factor for injury in elite football: a prospective study over two consecutive seasons. Br J Sports Med. 2006;40(9):767–72.

Fulton J, et al. Injury risk is altered by previous injury: a systematic review of the literature and presentation of causative neuromuscular factors. Int J Sports Phys Ther. 2014;9(5):583–95.

Toohey LA, et al. Is subsequent lower limb injury associated with previous injury? A systematic review and meta-analysis. Br J Sports Med. 2017;51(23):1670–8.

Jacobsson J, Timpka T. Classification of prevention in sports medicine and epidemiology. Sports Med. 2015;45(11):1483–7.

Bourne MN, et al. An evidence-based framework for strengthening exercises to prevent hamstring injury. Sports Med. 2017.

Delahunt E, Fitzpatrick H, Blake C. Pre-season adductor squeeze test and HAGOS function sport and recreation subscale scores predict groin injury in Gaelic football players. Phys Ther Sport. 2017;23:1–6.

O’Neill S, Watson PJ, Barry S. A Delphi study of risk factors for Achilles tendinopathy-opinions of world tendon experts. Int J Sports Phys Ther. 2016;11(5):684–97.

Neal BS, Lack SD. Risk factors for patellofemoral pain: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Br J Sports Med. 2019;53:270–81.

Anderson MJ, et al. A systematic summary of systematic reviews on the topic of the anterior cruciate ligament. Orthop J Sports Med. 2016;4(3):2325967116634074.

Thorborg K, et al. Eccentric and isometric hip adduction strength in male soccer players with and without adductor-related groin pain: an assessor-blinded comparison. Orthop J Sports Med. 2014;2(2):2325967114521778.

Nunes GS, Barton CJ, Serrao FV. Hip rate of force development and strength are impaired in females with patellofemoral pain without signs of altered gluteus medius and maximus morphology. J Sci Med Sport. 2017.

Angelozzi M, et al. Rate of force development as an adjunctive outcome measure for return-to-sport decisions after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 2012;42(9):772–80.

Wang HK, et al. Evoked spinal reflexes and force development in elite athletes with middle-portion Achilles tendinopathy. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 2011;41(10):785–94.

Cobian DG, et al. Knee extensor rate of torque development before and after arthroscopic partial meniscectomy, with analysis of neuromuscular mechanisms. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 2017;47(12):945–56.

Kline PW, et al. Impaired quadriceps rate of torque development and knee mechanics after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction with patellar tendon autograft. Am J Sports Med. 2015;43(10):2553–8.

Opar DA, et al. Rate of torque and electromyographic development during anticipated eccentric contraction is lower in previously strained hamstrings. Am J Sports Med. 2013;41(1):116–25.

Doherty C, et al. Coordination and symmetry patterns during the drop vertical jump, 6-months after first-time lateral ankle sprain. J Orthop Res. 2015;33(10):1537–44.

Doherty C, et al. Recovery from a first-time lateral ankle sprain and the predictors of chronic ankle instability: a prospective cohort analysis. Am J Sports Med. 2016;44(4):995–1003.

King E. et al. Whole-body biomechanical differences between limbs exist 9 months after ACL reconstruction across jump/landing tasks. Scand J Med Sci Sports. 2018.

Gore SJ, Franklyn-Miller A. Is stiffness related to athletic groin pain? Scand J Med Sci Sports. 2018;28(6):1681–90.

Debenham JR, et al. Achilles tendinopathy alters stretch shortening cycle behaviour during a sub-maximal hopping task. J Sci Med Sport. 2016;19(1):69–73.

Maquirriain J. Leg stiffness changes in athletes with Achilles tendinopathy. Int J Sports Med. 2012;33(7):567–71.

Pruyn EC, et al. Relationship between leg stiffness and lower body injuries in professional Australian football. J Sports Sci. 2012;30(1):71–8.

Lorimer AV, Hume PA. Stiffness as a risk factor for achilles tendon injury in running athletes. Sports Med. 2016;46(12):1921–38.

O’Malley E, et al. Countermovement jump and isokinetic dynamometry as measures of rehabilitation status after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction. J Athletes Train. 2018;53(7):687–95.

Pratt KA, Sigward SM. Detection of knee power deficits following ACL reconstruction using wearable sensors. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 2018;48:1–24.

Lee DW, et al. Single-leg vertical jump test as a functional test after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction. Knee. 2018;25(6):1016–26.

Morin JB, Samozino P. Interpreting power-force-velocity profiles for individualized and specific training. Int J Sports Physiol Perform. 2016;11(2):267–72.

Lorenz DS, Reiman MP. Performance enhancement in the terminal phases of rehabilitation. Sports Health. 2011;3(5):470–80.

Macdonald B et al. The single-leg Roman chair hold is more effective than the Nordic hamstring curl in improving hamstring strength-endurance in Gaelic footballers with previous hamstring injury. J Strength Cond Res. 2018.

Beyer R, et al. Heavy slow resistance versus eccentric training as treatment for achilles tendinopathy: a randomized controlled trial. Am J Sports Med. 2015;43(7):1704–11.

Lack S, et al. Proximal muscle rehabilitation is effective for patellofemoral pain: a systematic review with meta-analysis. Br J Sports Med. 2015;49(21):1365–76.

Presland JD, et al. The effect of Nordic hamstring exercise training volume on biceps femoris long head architectural adaptation. Scand J Med Sci Sports. 2018;28(7):1775–83.

Newton RU, Kraemer WJ. Developing explosive muscular power: implications for a mixed methods training strategy. Strength Cond J. 1994;16(5):20–31.

Kawamori N, Haff GG. The optimal training load for the development of muscular power. J Strength Cond Res. 2004;18(3):675–84.

Cormie P, McGuigan MR, Newton RU. Adaptations in athletic performance after ballistic power versus strength training. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2010;42(8):1582–98.

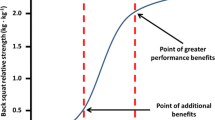

Suchomel TJ, et al. The importance of muscular strength: training considerations. Sports Med. 2018;48:765.

Rodríguez-Rosell D, et al. Physiological and methodological aspects of rate of force development assessment in human skeletal muscle. Clin Physiol Funct Imaging. 2018;38(5):743–62.

Cormie P, McGuigan MR, Newton RU. Developing maximal neuromuscular power: part 1—biological basis of maximal power production. Sports Med. 2011;41(1):17–38.

Hornsby WG, et al. What is the impact of muscle hypertrophy on strength and sport performance? Strength Cond J. 2018;40(6):99–111.

Taber CB, et al. Exercise-induced myofibrillar hypertrophy is a contributory cause of gains in muscle strength. Sports Med. 2019;49(7):993–7.

Hughes DC, Ellefsen S, Baar K. Adaptations to endurance and strength training. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Med. 2017;8(6).

Haff GG, Stone MH. Methods of developing power with special reference to football players. Strength Cond J. 2015;37(6):2–16.

Henneman E, Somjen G, Carpenter DO. Excitability and inhibitability of motoneurons of different sizes. J Neurophysiol. 1965;28(3):599–620.

Clark BC, et al. The power of the mind: the cortex as a critical determinant of muscle strength/weakness. J Neurophysiol. 2014;112(12):3219–26.

Stone MH, et al. The importance of isometric maximum strength and peak rate-of-force development in sprint cycling. J Strength Cond Res. 2004;18(4):878–84.

Aagaard P, et al. Increased rate of force development and neural drive of human skeletal muscle following resistance training. J Appl Physiol (1985). 2002;93(4):1318–26.

Haff GG, Nimphius S. Training principles for power. Strength Cond Res. 2012;34(6):2–12.

Taber C, et al. Roles of maximal strength and rate of force development in maximizing muscular power. Strength Cond Res. 2016;38(1):71–8.

Crewther BT, et al. Baseline strength can influence the ability of salivary free testosterone to predict squat and sprinting performance. J Strength Cond Res. 2012;26(1):261–8.

Comfort P, Thomas C. Changes in dynamic strength index in response to strength training. Sports. 2018;6:176.

James LP, et al. The impact of strength level on adaptations to combined weightlifting, plyometric, and ballistic training. Scand J Med Sci Sports. 2018;28(5):1494–505.

Bohm S, Mersmann F, Arampatzis A. Human tendon adaptation in response to mechanical loading: a systematic review and meta-analysis of exercise intervention studies on healthy adults. Sports Med Open. 2015;1(1):7.

Kidgell DJ, et al. Corticospinal responses following strength training: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur J Neurosci. 2017;46(11):2648–61.

Watson SL, et al. High-intensity resistance and impact training improves bone mineral density and physical function in postmenopausal women with osteopenia and osteoporosis: the LIFTMOR randomized controlled trial. J Bone Miner Res. 2018;33(2):211–20.

Magnusson SP, Kjaer M. The impact of loading, unloading, ageing and injury on the human tendon. J Physiol. 2019;597(5):1283–98.

Goodman CA, Hornberger TA, Robling AG. Bone and skeletal muscle: key players in mechanotransduction and potential overlapping mechanisms. Bone. 2015;80:24–36.

Grzelak P, et al. Hypertrophied cruciate ligament in high performance weightlifters observed in magnetic resonance imaging. Int Orthop. 2012;36(8):1715–9.

Ploutz L, et al. Effect of resistance training on muscle use during exercise. J Appl Physiol. 1994;76:1675–81.

Stone M, Stone M, Sands W. Principles and practice or resistance training. New York: Human Kinetics; 2007.

Ploutz LL, et al. Effect of resistance training on muscle use during exercise. J Appl Physiol (1985). 1994;76(4):1675–81.

Baroni BM et al. Hamstring-to-quadriceps torque ratios of professional male soccer players: a systematic review. J Strength Cond Res. 2018.

Grindem H, et al. Simple decision rules can reduce reinjury risk by 84% after ACL reconstruction: the Delaware–Oslo ACL cohort study. Br J Sports Med. 2016;50(13):804–8.

Bourne MN, et al. Eccentric knee flexor strength and risk of hamstring injuries in Rugby Union: a prospective study. Am J Sports Med. 2015;43(11):2663–70.

Kyritsis P, et al. Likelihood of ACL graft rupture: not meeting six clinical discharge criteria before return to sport is associated with a four times greater risk of rupture. Br J Sports Med. 2016;50(15):946–51.

Adams D, et al. Current concepts for anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction: a criterion-based rehabilitation progression. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 2012;42(7):601–14.

Ardern CL, et al. 2016 Consensus statement on return to sport from the First World Congress in Sports Physical Therapy, Bern. Br J Sports Med. 2016;50(14):853.

Grindem H, et al. How does a combined preoperative and postoperative rehabilitation programme influence the outcome of ACL reconstruction 2 years after surgery? A comparison between patients in the Delaware–Oslo ACL Cohort and the Norwegian National Knee Ligament Registry. Br J Sports Med. 2015;49(6):385–9.

Lauersen JB, Bertelsen DM, Andersen LB. The effectiveness of exercise interventions to prevent sports injuries: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. Br J Sports Med. 2014;48(11):871.

Malone S, et al. Can the workload-injury relationship be moderated by improved strength, speed and repeated-sprint qualities? J Sci Med Sport. 2019;22(1):29–34.

Holden S, Barton CJ. ‘What should I prescribe?’: time to improve reporting of resistance training programmes to ensure accurate translation and implementation. Br J Sports Med. 2018;53:264–5.

Holden S, et al. How can we implement exercise therapy for patellofemoral pain if we don’t know what was prescribed? A systematic review. Br J Sports Med. 2018;52(6):385.

Murphy M, et al. Rate of improvement of pain and function in mid-portion achilles tendinopathy with loading protocols: a systematic review and longitudinal meta-analysis. Sports Med. 2018;48(8):1875–91.

Malliaras P, et al. Achilles and patellar tendinopathy loading programmes: a systematic review comparing clinical outcomes and identifying potential mechanisms for effectiveness. Sports Med. 2013;43(4):267–86.

Ishoi L, et al. Large eccentric strength increase using the Copenhagen Adduction exercise in football: a randomized controlled trial. Scand J Med Sci Sports. 2016;26(11):1334–42.

Yousefzadeh A, et al. The effect of therapeutic exercise on long-standing adductor-related groin pain in athletes: modified Holmich protocol. Rehabil Res Pract. 2018;2018:10.

Sonnery-Cottet B, Saithna A. Arthrogenic muscle inhibition after ACL reconstruction: a scoping review of the efficacy of interventions. Br J Sports Med. 2019;53(5):289–98.

Hopkins JT, Ingersoll CD. Arthrogenic muscle inhibition: a limiting factor in joint rehabilitation. J Sport Rehabil. 2000;9(2):135–59.

Rice DA, McNair PJ. Quadriceps arthrogenic muscle inhibition: neural mechanisms and treatment perspectives. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2010;40(3):250–66.

Pietrosimone BG, et al. Neural excitability alterations after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction. J Athl Train. 2015;50(6):665–74.

Roy JS, et al. Beyond the joint: the role of central nervous system reorganizations in chronic musculoskeletal disorders. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 2017;47(11):817–21.

Chang WJ, et al. Altered primary motor cortex structure, organization, and function in chronic pain: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Pain. 2018;19(4):341–59.

Te M, et al. Primary motor cortex organization is altered in persistent patellofemoral pain. Pain Med. 2017;18(11):2224–34.

Fyfe JJ, et al. The role of neuromuscular inhibition in hamstring strain injury recurrence. J Electromyogr Kinesiol. 2013;23(3):523–30.

Brockett CL, Morgan DL, Proske U. Predicting hamstring strain injury in elite athletes. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2004;36(3):379–87.

Roig M, et al. The effects of eccentric versus concentric resistance training on muscle strength and mass in healthy adults: a systematic review with meta-analysis. Br J Sports Med. 2009;43(8):556–68.

Silder A, et al. MR observations of long-term musculotendon remodeling following a hamstring strain injury. Skelet Radiol. 2008;37(12):1101–9.

Bourne MN, et al. Eccentric knee flexor weakness in elite female footballers 1–10 years following anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction. Phys Ther Sport. 2019;37:144–9.

Brughelli M, et al. Contralateral leg deficits in kinetic and kinematic variables during running in Australian rules football players with previous hamstring injuries. J Strength Cond Res. 2010;24(9):2539–44.

Lord C, et al. Greater loss of horizontal force after a repeated-sprint test in footballers with a previous hamstring injury. J Sci Med Sport. 2019;22(1):16–21.

Charlton PC, et al. Knee flexion not hip extension strength is persistently reduced following hamstring strain injury in Australian Football athletes: implications for Periodic Health Examinations. J Sci Med Sport. 2018;21(10):999–1003.

Rathleff MS, et al. Is hip strength a risk factor for patellofemoral pain? A systematic review and meta-analysis. Br J Sports Med. 2014;48(14):1088.

Rio E, et al. Tendon neuroplastic training: changing the way we think about tendon rehabilitation: a narrative review. Br J Sports Med. 2016;50(4):209–15.

O’Neill S, Barry S, Watson P. Plantarflexor strength and endurance deficits associated with mid-portion Achilles tendinopathy: the role of soleus. Phys Ther Sport. 2019;37:69–76.

Thorborg K. Why hamstring eccentrics are hamstring essentials. Br J Sports Med. 2012;46(7):463–5.

Kristensen J, Franklyn-Miller A. Resistance training in musculoskeletal rehabilitation: a systematic review. Br J Sports Med. 2012;46(10):719.

Booth J, et al. Exercise for chronic musculoskeletal pain: a biopsychosocial approach. Musculoskelet Care. 2017;15(4):413–21.

American College of Sports Medicine position stand. Progression models in resistance training for healthy adults. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2009;41(3):687–708.

Mersmann F, Bohm S, Arampatzis A. Imbalances in the development of muscle and tendon as risk factor for tendinopathies in youth athletes: a review of current evidence and concepts of prevention. Front Physiol. 2017;8:987.

Schoenfeld BJ, et al. Strength and hypertrophy adaptations between low- vs high-load resistance training: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Strength Cond Res. 2017;31(12):3508–23.

Schoenfeld BJ, Grgic J, Krieger J. How many times per week should a muscle be trained to maximize muscle hypertrophy? A systematic review and meta-analysis of studies examining the effects of resistance training frequency. J Sports Sci. 2018;37:1–10.

Hughes L, et al. Blood flow restriction training in clinical musculoskeletal rehabilitation: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Br J Sports Med. 2017;51(13):1003.

Kidgell DJ, et al. Increased cross-education of muscle strength and reduced corticospinal inhibition following eccentric strength training. Neuroscience. 2015;300:566–75.

Cirer-Sastre R, Beltrán-Garrido JV, Corbi F. Contralateral effects after unilateral strength training: a meta-analysis comparing training loads. J Sports Sci Med. 2017;16(2):180–6.

Vaegter HB. Exercising non-painful muscles can induce hypoalgesia in individuals with chronic pain. Scand J Pain. 2017;15:60–1.

Naugle KM, Fillingim RB, Riley I. A meta-analytic review of the hypoalgesic effects of exercise. J Pain. 2012;13(12):1139–50.

Rio E, et al. Isometric contractions are more analgesic than isotonic contractions for patellar tendon pain: an in-season randomized clinical trial. Clin J Sport Med. 2017;27(3):253–9.

Rio E et al. isometric exercise to reduce pain in patellar tendinopathy in-season; is it effective “on the road?”. Clin J Sport Med. 2017.

O’Neill S, et al. Acute sensory and motor response to 45-s heavy isometric holds for the plantar flexors in patients with Achilles tendinopathy. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2018;27(9):2765–73.

Riel H, Vicenzino B. The effect of isometric exercise on pain in individuals with plantar fasciopathy: a randomized crossover trial. Scand J Med Sci Sports. 2018;28(12):2643–50.

Lemley KJ, Hunter SK, Bement MK. Conditioned pain modulation predicts exercise-induced hypoalgesia in healthy adults. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2015;47(1):176–84.

Naugle KM, et al. Physical activity behavior predicts endogenous pain modulation in older adults. Pain. 2017;158(3):383–90.

Naugle KM, et al. Isometric exercise as a test of pain modulation: effects of experimental pain test, psychological variables, and sex. Pain Med. 2014;15(4):692–701.

Sluka KA, Frey-Law L, Hoeger Bement M. Exercise-induced pain and analgesia? Underlying mechanisms and clinical translation. Pain. 2018;159(Suppl 1):S91–7.

Coombes BK, Tucker K. Achilles and patellar tendinopathy display opposite changes in elastic properties: a shear wave elastography study. Scand J Med Sci Sports. 2018;28(3):1201–8.

Oranchuk DJ, et al. Isometric training and long-term adaptations; effects of muscle length, intensity and intent: a systematic review. Scand J Med Sci Sports. 2019;29(4):484–503.

Alegre LM, et al. Effects of isometric training on the knee extensor moment-angle relationship and vastus lateralis muscle architecture. Eur J Appl Physiol. 2014;114(11):2437–46.

Kubo K, et al. Effects of isometric training at different knee angles on the muscle-tendon complex in vivo. Scand J Med Sci Sports. 2006;16(3):159–67.

Noorkoiv M, Nosaka K, Blazevich AJ. Neuromuscular adaptations associated with knee joint angle-specific force change. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2014;46(8):1525–37.

de Ruiter CJ, et al. Knee angle-dependent oxygen consumption during isometric contractions of the knee extensors determined with near-infrared spectroscopy. J Appl Physiol (1985). 2005;99(2):579–86.

Huang H, et al. Isokinetic angle-specific moments and ratios characterizing hamstring and quadriceps strength in anterior cruciate ligament deficient knees. Sci Rep. 2017;7(1):7269.

Eitzen I, et al. Anterior cruciate ligament-deficient potential copers and noncopers reveal different isokinetic quadriceps strength profiles in the early stage after injury. Am J Sports Med. 2010;38(3):586–93.

Rio E, et al. Isometric exercise induces analgesia and reduces inhibition in patellar tendinopathy. Br J Sports Med. 2015;49(19):1277–83.

Maffiuletti NA, et al. Rate of force development: physiological and methodological considerations. Eur J Appl Physiol. 2016;116(6):1091–116.

Brazier J, et al. Lower extremity stiffness: considerations for testing, performance enhancement, and injury risk. J Strength Cond Res. 2019;33(4):1156–66.

Andersen LL, et al. Early and late rate of force development: differential adaptive responses to resistance training? Scand J Med Sci Sports. 2010;20(1):e162–9.

Tillin NA, Pain MT, Folland JP. Short-term training for explosive strength causes neural and mechanical adaptations. Exp Physiol. 2012;97(5):630–41.

Balshaw TG, et al. Training-specific functional, neural, and hypertrophic adaptations to explosive- vs. sustained-contraction strength training. J Appl Physiol (1985). 2016;120(11):1364–73.

Butler RJ, Crowell HP 3rd, Davis IM. Lower extremity stiffness: implications for performance and injury. Clin Biomech (Bristol, Avon). 2003;18(6):511–7.

Suchomel TJ, Comfort P, Lake JP. Enhancing the force–velocity profile of athletes using weightlifting derivatives. Strength Cond J. 2017;39(1):10–20.

Jiménez-Reyes P, et al. Effectiveness of an individualized training based on force–velocity profiling during jumping. Front Physiol. 2016;7:677.

Mendiguchia J, et al. Field monitoring of sprinting power-force-velocity profile before, during and after hamstring injury: two case reports. J Sports Sci. 2016;34(6):535–41.

Aagaard P. Spinal and supraspinal control of motor function during maximal eccentric muscle contraction: Effects of resistance training. J Sport Health Sci. 2018;7(3):282–93.

Nishikawa K. Eccentric contraction: unraveling mechanisms of force enhancement and energy conservation. J Exp Biol. 2016;219(2):189.

Wagle JP, et al. Accentuated eccentric loading for training and performance: a review. Sports Med. 2017;47(12):2473–95.

Harden M, et al. An evaluation of supramaximally loaded eccentric leg press exercise. J Strength Cond Res. 2018;32(10):2708–14.

Tallent J, et al. Enhanced corticospinal excitability and volitional drive in response to shortening and lengthening strength training and changes following detraining. Front Physiol. 2017;8:57.

Beattie K, et al. The relationship between maximal strength and reactive strength. Int J Sports Physiol Perform. 2017;12(4):548–53.

Flanagan EP, Comyns TM. The use of contact time and the reactive strength index to optimize fast stretch-shortening cycle training. Strength Cond J. 2008;30(5):32–8.

Pedley JS, et al. Drop jump: a technical model for scientific application. Strength Cond J. 2017;39(5):36–44.

McBride JM, McCaulley GO, Cormie P. Influence of preactivity and eccentric muscle activity on concentric performance during vertical jumping. J Strength Cond Res. 2008;22(3):750–7.

Asadi A, et al. The effects of plyometric training on change-of-direction ability: a meta-analysis. Int J Sports Physiol Perform. 2016;11(5):563–73.

Lum D, et al. Effects of intermittent sprint and plyometric training on endurance running performance. J Sport Health Sci. 2019;8(5):471–7.

Butler RJ, Crowell I, Davis IM. Lower extremity stiffness: implications for performance and injury. Clin Biomech. 2003;18(6):511–7.

Child S, et al. Mechanical properties of the achilles tendon aponeurosis are altered in athletes with achilles tendinopathy. Am J Sports Med. 2010;38(9):1885–93.

Obst SJ, et al. Are the mechanical or material properties of the achilles and patellar tendons altered in tendinopathy? A systematic review with meta-analysis. Sports Med. 2018;48(9):2179–98.

Turner AN, Jeffreys I. The stretch-shortening cycle: proposed mechanisms and methods for enhancement. Strength Cond J. 2010;32(4):87–99.

Maloney SJ, et al. Unilateral stiffness interventions augment vertical stiffness and change of direction speed. J Strength Cond Res. 2019;33(2):372–9.

Maloney SJ, et al. Do stiffness and asymmetries predict change of direction performance? J Sports Sci. 2017;35(6):547–56.

Lepley LK, Palmieri-Smith R. Effect of eccentric strengthening after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction on quadriceps strength. J Sport Rehabil. 2013;22(2):150–6.

van der Horst N, et al. The preventive effect of the nordic hamstring exercise on hamstring injuries in amateur soccer players: a randomized controlled trial. Am J Sports Med. 2015;43(6):1316–23.

Arnason A, et al. Prevention of hamstring strains in elite soccer: an intervention study. Scand J Med Sci Sports. 2008;18(1):40–8.

Petersen J, et al. Preventive effect of eccentric training on acute hamstring injuries in men’s soccer: a cluster-randomized controlled trial. Am J Sports Med. 2011;39(11):2296–303.

Geremia JM, et al. Effects of high loading by eccentric triceps surae training on Achilles tendon properties in humans. Eur J Appl Physiol. 2018;118(8):1725–36.

Aune AAG, et al. Acute and chronic effects of foam rolling vs eccentric exercise on ROM and force output of the plantar flexors. J Sports Sci. 2018;37:1–8.

Ghigiarelli JJ, et al. The effects of a 7-week heavy elastic band and weight chain program on upper-body strength and upper-body power in a sample of division 1-AA football players. J Strength Cond Res. 2009;23(3):756–64.

Ardern CL, et al. Return to sport following anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction surgery: a systematic review and meta-analysis of the state of play. Br J Sports Med. 2011;45(7):596–606.

Burgi CR, et al. Which criteria are used to clear patients to return to sport after primary ACL reconstruction? A scoping review. Br J Sports Med. 2019;53(18):1154–61.

Comfort P, McMahon JJ, Suchomel TJ. Optimizing squat technique—revisited. Strength Cond J. 9000. (Publish Ahead of Print).

Kiely J. Periodization theory: confronting an inconvenient truth. Sports Med. 2018;48(4):753–64.

Cunanan AJ, et al. The general adaptation syndrome: a foundation for the concept of periodization. Sports Med. 2018;48(4):787–97.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

Luca Maestroni, Paul Read, Chris Bishop and Anthony Turner declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Funding

No financial support was received for the preparation of this manuscript

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Maestroni, L., Read, P., Bishop, C. et al. Strength and Power Training in Rehabilitation: Underpinning Principles and Practical Strategies to Return Athletes to High Performance. Sports Med 50, 239–252 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40279-019-01195-6

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40279-019-01195-6