Abstract

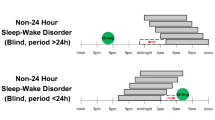

Non-24-h sleep–wake disorder (non-24) is a circadian rhythm disorder occurring in 55–70% of totally blind individuals (those lacking conscious light perception) in which the 24-h biological clock (central, hypothalamic, circadian pacemaker) is no longer synchronized, or entrained, to the 24-h day. Instead, the overt rhythms controlled by the biological clock gradually shift progressively earlier or later (free run) in accordance with the clock’s near-24-h period, resulting in a recurrent pattern of daytime hypersomnolence and night-time insomnia. Orally administered melatonin and the melatonin agonist tasimelteon have been shown to entrain (synchronize) the circadian clock, resulting in improvements in night-time sleep and daytime alertness. We review the basic principles of circadian rhythms necessary to understand and treat non-24. The time of melatonin or tasimelteon administration must be considered carefully. For most individuals, those with circadian periods longer than 24 h, low-dose melatonin should be administered about 6 h before the desired bedtime, while in a minority, those with circadian periods shorter than 24 h (more commonly female individuals and African–Americans), melatonin should be administered at the desired wake time. Small doses (e.g., 0.5 mg of melatonin) that are not soporific would thus be preferable. Administration of melatonin or tasimelteon at bedtime will entrain individuals with non-24 but at an abnormally late time, resulting in continued problems with sleep and alertness. To date, tasimelteon has only been administered 1 h before the target bedtime in patients with non-24. Issues of cost, dose accuracy, and purity may figure into the decision of whether tasimelteon or melatonin is chosen to treat non-24. However, there are no head-to-head studies comparing efficacy, and studies to date show comparable rates of treatment success (entrainment).

Similar content being viewed by others

References

American Academy of Sleep Medicine. The international classification of sleep disorders. Diagnostic and coding manual. 3rd ed. Darien: American Academy of Sleep Medicine; 2014.

Keating GM. Tasimelteon: a review in non-24-hour sleep–wake disorder in totally blind individuals. CNS Drugs. 2016;30:461–8.

Dhillon S, Clarke M. Tasimelteon: first global approval. Drugs. 2014;74(4):505–11.

Buhr ED, Takahashi JS. Molecular components of the mammalian circadian clock. Handb Exp Pharmacol. 2013;217:3–27.

LeGates TA, Fernandez DC, Hattar S. Light as a central modulator of circadian rhythms, sleep and affect. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2014;15(7):443–54.

Aschoff J, Wever R. The circadian system of man. In: Aschoff J, editor. Handbook of behavioral neurobiology. Biological rhythms, vol. 4. New York: Plenum Press; 1981. p. 311–31.

Czeisler CA, Duffy JF, Shanahan TL, et al. Stability, precision, and near-24-hour period of the human circadian pacemaker. Science. 1999;284:2177–81.

Burgess HJ, Eastman CI. Human tau in an ultradian light–dark cycle. J Biol Rhythms. 2008;23(4):374–6.

Duffy JF, Cain SW, Chang AM, et al. Sex difference in the near-24-hour intrinsic period of the human circadian timing system. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2011;108(Suppl 3):15602–8.

Eastman CI, Suh C, Tomaka VA, Crowley SJ. Circadian rhythm phase shifts and endogenous free-running circadian period differ between African–Americans and European–Americans. Sci Rep. 2015;5:8381.

Eastman CI, Tomaka VA, Crowley SJ. Circadian rhythms of European and African–Americans after a large delay of sleep as in jet lag and night work. Sci Rep. 2016;6:36716.

Eastman CI, Molina TA, Dziepak ME, Smith MR. Blacks (African Americans) have shorter free-running circadian periods than whites (Caucasian Americans). Chronobiol Int. 2012;29(8):1072–7.

Lewy AJ, Sack RL. The dim light melatonin onset as a marker for circadian phase position. Chronobiol Int. 1989;6(1):93–102.

Lewy AJ, Cutler NL, Sack RL. The endogenous melatonin profile as a marker of circadian phase position. J Biol Rhythms. 1999;14(3):227–36.

Klerman EB, Gershengorn HB, Duffy JF, Kronauer RE. Comparisons of the variability of three markers of the human circadian pacemaker. J Biol Rhythms. 2002;17(2):181–93.

Benloucif S, Burgess HJ, Klerman EB, et al. Measuring melatonin in humans. J Clin Sleep Med. 2008;4(1):66–9.

Emens JS, Yuhas K, Rough J, et al. Phase angle of entrainment in morning- and evening-types under naturalistic conditions. Chronobiol Int. 2009;26(3):474–93.

Burgess HJ, Fogg LF. Individual differences in the amount and timing of salivary melatonin secretion. PLoS One. 2008;3(8):e3055.

Martin SK, Eastman CI. Sleep logs of young adults with self-selected sleep times predict the dim light melatonin onset. Chronobiol Int. 2002;19(4):695–707.

Burgess HJ, Eastman CI. The dim light melatonin onset following fixed and free sleep schedules. J Sleep Res. 2005;14:229–37.

Arendt J, Bojkowski C, Franey C, et al. Immunoassay of 6-hydroxymelatonin sulfate in human plasma and urine: abolition of the urinary 24-hour rhythm with atenolol. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1985;60(6):1166–73.

Skene DJ, Lockley SW, James K, Arendt J. Correlation between urinary cortisol and 6-sulphatoxymelatonin rhythms in field studies of blind subjects. Clin Endocrinol. 1999;50:715–9.

Miles LE, Raynal DM, Wilson MA. Blind man living in normal society has circadian rhythms of 24.9 hours. Science. 1977;198(4315):421–3.

Lewy AJ, Newsome DA. Different types of melatonin circadian secretory rhythms in some blind subjects. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1983;56:1103–7.

Sack RL, Lewy AJ, Blood ML, et al. Circadian rhythm abnormalities in totally blind people: incidence and clinical significance. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1992;75:127–34.

Klein T, Martens H, Dijk DJ, et al. Circadian sleep regulation in the absence of light perception: chronic non-24-hour circadian rhythm sleep disorder in a blind man with a regular 24-hour sleep–wake schedule. Sleep. 1993;16:333–43.

Lockley SW, Skene DJ, Arendt J, et al. Relationship between melatonin rhythms and visual loss in the blind. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1997;82:3763–70.

Klerman EB, Rimmer DW, Dijk DJ, et al. Nonphotic entrainment of the human circadian pacemaker. Am J Physiol. 1998;274:R991–6.

Lockley SW, Dressman MA, Licamele L, et al. Tasimelteon for non-24-hour sleep–wake disorder in totally blind people (SET and RESET): two multicentre, randomised, double-masked, placebo-controlled phase 3 trials. Lancet. 2015;386:1754–64.

Emens JS, Laurie AL, Songer JB, Lewy AJ. Non-24-hour disorder in blind individuals revisited: variability and the influence of environmental time cues. Sleep. 2013;36(07):1091–100.

Leger D, Guilleminault C, Santos C, Paillard M. Sleep/wake cycles in the dark: sleep recorded by polysomnography in 26 totally blind subjects compared to controls. Clin Neurophysiol. 2002;113(10):1607–14.

Leger D, Guilleminault C, Defrance R, et al. Prevalence of sleep/wake disorders in persons with blindness. Clin Sci. 1999;97:193–9.

Lockley SW, Skene DJ, Butler LJ, Arendt J. Sleep and activity rhythms are related to circadian phase in the blind. Sleep. 1999;22:616–23.

Sack RL, Brandes RW, Kendall AR, Lewy AJ. Entrainment of free-running circadian rhythms by melatonin in blind people. N Engl J Med. 2000;343(15):1070–7.

Emens JS, Lewy AJ, Lefler BJ, Sack RL. Relative coordination to unknown “weak zeitgebers” in free-running blind individuals. J Biol Rhythms. 2005;20:159–67.

Karatsoreos IN, Bhagat S, Bloss EB, et al. Disruption of circadian clocks has ramifications for metabolism, brain, and behavior. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2011;108(4):1657–62.

Scheer FA, Hilton MF, Mantzoros CS, Shea SA. Adverse metabolic and cardiovascular consequences of circadian misalignment. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2009;106(11):4453–8.

LeGates TA, Altimus CM, Wang H, et al. Aberrant light directly impairs mood and learning through melanopsin-expressing neurons. Nature. 2012;491(7425):594–8.

Emens J, Lewy AJ, Laurie AL, Songer JB. Rest-activity cycle and melatonin rhythm in blind free-runners have similar periods. J Biol Rhythms. 2010;25(5):381–4.

Burgess HJ, Wyatt JK, Park M, Fogg LF. Home circadian phase assessments with measures of compliance yield accurate dim light melatonin onsets. Sleep. 2015;38(6):889–97.

Keijzer H, Smits MG, Duffy JF, Curfs LM. Why the dim light melatonin onset (DLMO) should be measured before treatment of patients with circadian rhythm sleep disorders. Sleep Med Rev. 2014;18(4):333–9.

Redman J, Armstrong S, Ng KT. Free-running activity rhythms in the rat: entrainment by melatonin. Science. 1983;219(4588):1089–91.

Reppert SM, Weaver DR, Godson C. Melatonin receptors step into the light: cloning and classification of subtypes. Trends Pharmocol Sci. 1996;17:100–2.

Dubocovich ML. Melatonin receptors: role on sleep and circadian rhythm regulation. Sleep Med. 2007;8(Suppl 3):34–42.

Attenburrow MEJ, Dowling BA, Sargent PA, et al. Melatonin phase advances circadian rhythm. Psychopharmacol. 1995;121:503–5.

Deacon S, Arendt J. Melatonin-induced temperature suppression and its acute phase-shifting effects correlate in a dose-dependent manner in humans. Brain Res. 1995;688(1–2):77–85.

Mallo C, Zaidan R, Faure A, et al. Effects of a four-day nocturnal melatonin treatment on the 24 h plasma melatonin, cortisol and prolactin profiles in humans. Acta Endocrinol. 1988;119:474–80.

Krauchi K, Cajochen C, Mori D, et al. Early evening melatonin and S-20098 advance circadian phase and nocturnal regulation of core body temperature. Am J Physiol. 1997;272:R1178–88.

Nagtegaal JE, Kerkhof GA, Smits MG, et al. Delayed sleep phase syndrome: a placebo-controlled cross-over study on the effects of melatonin administered five hours before the individual dim light melatonin onset. J Sleep Res. 1998;7(2):135–43.

Samel A, Wegmann HM, Vejvoda M, et al. Influence of melatonin treatment on human circadian rhythmicity before and after a simulated 9-hr time shift. J Biol Rhythms. 1991;6:235–48.

Yang CM, Spielman AJ, D’Ambrosio P, et al. A single dose of melatonin prevents the phase delay associated with a delayed weekend sleep pattern. Sleep. 2001;24:272–81.

Sharkey KM, Eastman CI. Melatonin phase shifts human circadian rhythms in a placebo-controlled simulated night-work study. Am J Physiol. 2002;282:R454–63.

Wirz-Justice A, Krauchi K, Cajochen C, et al. Evening melatonin and bright light administration induce additive phase shifts in dim light melatonin onset. J Pineal Res. 2004;36:192–4.

Rajaratnam SMW, Dijk DJ, Middleton B, et al. Melatonin phase-shifts human circadian rhythms with no evidence of changes in the duration of endogenous melatonin secretion or the 24-hour production of reproductive hormones. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2003;88:4303–9.

Paul MA, Miller JC, Gray GW, et al. Melatonin treatment for eastward and westward travel preparation. Psychopharmacol (Berl). 2010;208(3):377–86.

Paul MA, Gray GW, Lieberman HR, et al. Phase advance with separate and combined melatonin and light treatment. Psychopharmacol (Berl). 2011;214(2):515–23.

Crowley SJ, Eastman CI. Melatonin in the afternoons of a gradually advancing sleep schedule enhances the circadian rhythm phase advance. Psychopharmacol (Berl). 2013;225(4):825–37.

Burke TM, Markwald RR, Chinoy ED, et al. Combination of light and melatonin time cues for phase advancing the human circadian clock. Sleep. 2013;36(11):1617–24.

Lewy AJ, Bauer VK, Ahmed S, et al. The human phase response curve (PRC) to melatonin is about 12 hours out of phase with the PRC to light. Chronobiol Int. 1998;15:71–83.

Burgess HJ, Revell VL, Eastman CI. A three pulse phase response curve to three milligrams of melatonin in humans. J Physiol. 2008;586(2):639–47.

Burgess HJ, Revell VL, Molina TA, Eastman CI. Human phase response curves to three days of daily melatonin: 0.5 mg versus 3.0 mg. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2010;95(7):3325–31.

Lockley SW, Skene DJ, James K, et al. Melatonin administration can entrain the free-running circadian system of blind subjects. J Endocrinol. 2000;164(1):R1–6.

Lewy AJ, Emens JS, Sack RL, et al. Low, but not high, doses of melatonin entrained a free-running blind person with long circadian period. Chronobiol Int. 2002;19(3):649–58.

Lewy AJ, Bauer VK, Hasler BP, et al. Capturing the circadian rhythms of free-running blind people with 0.5 mg melatonin. Brain Res. 2001;918:96–100.

Hack LM, Lockley SW, Arendt J, Skene DJ. The effects of low-dose 0.5-mg melatonin on the free-running circadian rhythms of blind subjects. J Biol Rhythms. 2003;18(5):420–9.

Lewy AJ, Emens JS, Lefler BJ, et al. Melatonin entrains free-running blind people according to a physiological dose-response curve. Chronobiol Int. 2005;22(6):1093–106.

Sack RL, Lewy AJ, Blood ML, et al. Melatonin administration to blind people: phase advances and entrainment. J Biol Rhythms. 1991;6(3):249–61.

Lewy AJ, Emens JS, Bernert RA, Lefler BJ. Eventual entrainment of the human circadian pacemaker by melatonin is independent of the circadian phase of treatment initiation: clinical implications. J Biol Rhythms. 2004;19(1):68–75.

Emens J, Lewy A, Yuhas K, et al. Melatonin entrains free-running blind individuals with circadian periods less than 24 hours. Sleep. 2006;29:A62.

Revell VL, Burgess HJ, Gazda CJ, et al. Advancing human circadian rhythms with afternoon melatonin and morning intermittent bright light. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2006;91(1):54–9.

Suhner A, Schlagenhauf P, Tschopp A, et al. Impact of melatonin on driving performance. J Travel Med. 1998;5(1):7–13.

Auger RR, Burgess HJ, Emens JS, et al. Clinical practice guideline for the treatment of intrinsic circadian rhythm sleep–wake disorders: advanced sleep–wake phase disorder (ASWPD), delayed sleep–wake phase disorder (DSWPD), non-24-hour sleep–wake rhythm disorder (N24SWD), and irregular sleep–wake rhythm disorder (ISWRD): an update for 2015. An American Academy of Sleep Medicine clinical practice guideline. J Clin Sleep Med. 2015;11(10):1199–236.

Pittendrigh CS, Daan S. A functional analysis of circadian pacemakers in nocturnal rodents. I. The stability and lability of spontaneous frequency. J Comp Physiol. 1976;106:223–52.

Kripke DF, Elliott JA, Youngstedt SD, Rex KM. Circadian phase response curves to light in older and young women and men. J Circadian Rhythms. 2007;5(1):4.

Gunn PJ, Middleton B, Davies SK, et al. Sex differences in the circadian profiles of melatonin and cortisol in plasma and urine matrices under constant routine conditions. Chronobiol Int. 2016;33(1):39–50.

Rajaratnam SM, Polymeropoulos MH, Fisher DM, et al. Melatonin agonist tasimelteon (VEC-162) for transient insomnia after sleep-time shift: two randomised controlled multicentre trials. Lancet. 2009;373(9662):482–91.

Blask DE. Melatonin, sleep disturbance and cancer risk. Sleep Med Rev. 2009;13(4):257–64.

Reiter RJ, Tan DX, Erren TC, et al. Light-mediated perturbations of circadian timing and cancer risk: a mechanistic analysis. Integr Cancer Ther. 2009;8(4):354–60.

Goncalves AL, Martini Ferreira A, Ribeiro RT, et al. Randomised clinical trial comparing melatonin 3 mg, amitriptyline 25 mg and placebo for migraine prevention. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2016;87(10):1127–32.

Tasimelteon (Hetlioz) for non-24-hour sleep–wake disorder. Med Lett Drugs Ther. 2014;56(1441):34–5.

Herxheimer A, Petrie KJ. Melatonin for the prevention and treatment of jet lag. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2002. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD001520.

Buscemi N, Vandermeer B, Hooton N, et al. The efficacy and safety of exogenous melatonin for primary sleep disorders: a meta-analysis. J Gen Intern Med. 2005;20:1151–8.

Rubio-Sastre P, Scheer FA, Gomez-Abellan P, et al. Acute melatonin administration in humans impairs glucose tolerance in both the morning and evening. Sleep. 2014;37(10):1715–9.

Garaulet M, Gomez-Abellan P, Rubio-Sastre P, et al. Common type 2 diabetes risk variant in MTNR1B worsens the deleterious effect of melatonin on glucose tolerance in humans. Metabolism. 2015;64(12):1650–7.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Funding

No funding supported the writing of this review. National Institutes of Health Grants R01HL086934 and R01NR007677 to Charmane Eastman provided support for the studies that generated the phase response curves (Fig. 1).

Conflict of interest

Jonathan Emens has consulted regarding the drug tasimelteon but permanently severed all consulting relationships as required by the FDA to serve as an advisor for the Endocrinology and Metabolic Drugs Advisory Committee meeting on 12 January, 2015. Charmane Eastman served as an advisor to the FDA Peripheral and Central Nervous System Drugs Advisory Committee that recommended approval for tasimelteon for the treatment of non-24-h sleep–wake disorder in the totally blind on 14 November, 2013.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Emens, J.S., Eastman, C.I. Diagnosis and Treatment of Non-24-h Sleep–Wake Disorder in the Blind. Drugs 77, 637–650 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40265-017-0707-3

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40265-017-0707-3