Abstract

Objective

This study aimed to test the number needed to treat to benefit (NNTB) and to harm (NNTH), and the likelihood to be helped or harmed (LHH) when assessing benefits, risks, and benefit–risk ratios of disease-modifying treatments (DMTs) approved for relapsing–remitting multiple sclerosis (RRMS).

Methods

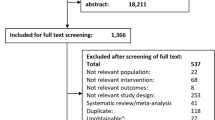

In May 2016, we conducted a systematic review using the PubMed and Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials databases to identify phase III, randomized controlled trials with a duration of ≥2 years that assessed first-line (dimethyl fumarate [DMF], glatiramer acetate [GA], β-interferons [IFN], and teriflunomide) or second-line (alemtuzumab, fingolimod, and natalizumab) DMTs in patients with RRMS. Meta-analyses were performed to estimate relative risks (RRs) on annualized relapse rate (ARR), proportion of relapse-free patients (PPR-F), disability progression (PP-F-CDPS3M), and safety outcomes. NNTB and NNTH values were calculated applying RRs to control event rates. LHH was calculated as NNTH/NNTB ratio.

Results

The lowest NNTBs on ARR, PPR-F, and PP-F-CDPS3M were found with IFN-β-1a-SC (NNTB 3, 95 % CI 2–4; NNTB 7, 95 % CI 4–18; NNTB 4, 95 % CI 3–7, respectively) and natalizumab (NNTB 2, 95 % CI 2–3; NNTB 4, 95 % CI 3–6; NNTB 9, 95 % CI 6–19, respectively). The lowest NNTH on adverse events leading to treatment discontinuation was found with IFN-β-1b (NNTH 14, 95 % 2–426) versus placebo; a protective effect was noted with alemtuzumab versus IFN-β-1a-SC (NNTB 22, 95 % 17–41). LHHs >1 were more frequent with IFN-β-1a-SC and natalizumab.

Conclusions

These metrics may be valuable for benefit–risk assessments, as they reflect baseline risks and are easily interpreted. Before making treatment decisions, clinicians must acknowledge that a higher RR reduction with drug A as compared with drug B (versus a common comparator in trial A and trial B, respectively) does not necessarily mean that the number of patients needed to be treated for one patient to encounter one aditional outcome of interest over a defined period of time is lower with drug A than with drug B. Overall, IFN-β-1a-SC and natalizumab seem to have the most favorable benefit–risk ratios among first- and second-line DMTs, respectively.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

English C, Aloi JJ. New FDA-approved disease-modifying therapies for multiple sclerosis. Clin Ther. 2015;37(4):691–715.

Ingwersen J, Aktas O, Hartung HP. Advances in and algorithms for the treatment of relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis. Neurotherapeutics. 2016;13(1):47–57.

European Medicines Agency. Committee for Medicinal Products for Human Use (CHMP). Reflection paper on benefit-risk assessment methods in the context of the evaluation of marketing authorisation applications of medicinal products for human use (EMEA/CHMP/15404/2007). 2007. Available from http://www.ema.europa.eu/docs/en_GB/document_library/Regulatory_and_procedural_guideline/2010/01/WC500069634.pdf. Accessed 10 May 2016.

U.S. Food and Drug Administration—Structured Approach to Benefit-Risk Assessment in Drug Regulatory Decision-Making. Draft Patient Drug User Free Act (PDUFA) I Implementation Plan. 2013. Available from http://www.fda.gov/downloads/ForIndustry/UserFees/PrescriptionDrugUserFee/UCM329758.pdf. Accessed 10 May 2016.

Yuan Z, Levitan B, Berlin JA. Benefit-risk assessment: to quantify or not to quantify, that is the question. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2011;20(6):653–6.

Mendes D, Alves C, Batel-Marques F. Number needed to harm in the post-marketing safety evaluation: results for rosiglitazone and pioglitazone. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2015;24(12):1259–70.

Mt-Isa S, Hallgreen CE, Wang N, IMI-PROTECT benefit-risk participants, et al. Balancing benefit and risk of medicines: a systematic review and classification of available methodologies. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2014;23(7):667–78.

Laupacis A, Sackett DL, Roberts RS. An assessment of clinically useful measures of the consequences of treatment. N Engl J Med. 1988;318(26):1728–33.

Cook D, Sackett D. The number needed to treat: a clinically usefull measure of treatment effect. BMJ. 1995;310:452–4.

Altman DG. Confidence intervals for the number needed to treat. BMJ. 1998;317(7168):1309–12.

Citrome L, Ketter TA. When does a difference make a difference? Interpretation of number needed to treat, number needed to harm, and likelihood to be helped or harmed. Int J Clin Pract. 2013;67(5):407–11.

Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG; PRISMA Group. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. Ann Intern Med. 2009;151(4):264–9, W64.

Higgins JPT, Green S, editors. Cochrane handbook for systematic reviews of interventions version 5.1.0 [updated March 2011]. The Cochrane Collaboration; 2011. Available from http://www.cochrane-handbook.org.

Tramacere I, Del Giovane C, Salanti G, et al. Immunomodulators and immunosuppressants for relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis: a network meta-analysis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2015;9:CD011381.

DerSimonian R, Laird N. Meta-analysis in clinical trials. Control Clin Trials. 1986;7(3):177–88.

Furukawa TA, Guyatt GH, Griffith LE. Can we individualize the ‘number needed to treat’? An empirical study of summary effect measures in meta-analyses. Int J Epidemiol. 2002;31(1):72–6.

Higgins JP, Thompson SG, Deeks JJ, Altman DG. Measuring inconsistency in meta-analysis. BMJ. 2003;327(7414):557–60.

Straus SE, Glasziou P, Richardson WS, Haynes RB. Evidence-based medicine: how to practice and teach it. London: Churchill Livingstone; 2011. p. 77–97.

Polman CH, O’Connor PW, Havrdova E, AFFIRM Investigators, et al. A randomized, placebo-controlled trial of natalizumab for relapsing multiple sclerosis. N Engl J Med. 2006;354(9):899–910.

O’Connor P, Filippi M, Arnason B, et al.; BEYOND Study Group, O’Connor P, Filippi M, Arnason B, Cook S, Goodin D, Hartung HP, Kappos L, Jeffery D, Comi G. 250 microg or 500 microg interferon beta-1b versus 20 mg glatiramer acetate in relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis: a prospective, randomised, multicentre study. Lancet Neurol. 2009;8(10):889–97.

Cohen JA, Coles AJ, Arnold DL, CARE-MS I investigators, et al. Alemtuzumab versus interferon beta 1a as first-line treatment for patients with relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis: a randomised controlled phase 3 trial. Lancet. 2012;380(9856):1819–28.

Coles AJ, Twyman CL, Arnold DL, CARE-MS II investigators, et al. Alemtuzumab for patients with relapsing multiple sclerosis after disease-modifying therapy: a randomised controlled phase 3 trial. Lancet. 2012;380(9856):1829–39.

Fox RJ, Miller DH, Phillips JT, CONFIRM Study Investigators, et al. Placebo-controlled phase 3 study of oral BG-12 or glatiramer in multiple sclerosis. N Engl J Med. 2012;367(12):1087–97.

Johnson KP, Brooks BR, Cohen JA, et al. Copolymer 1 reduces relapse rate and improves disability in relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis: results of a phase III multicenter, double-blind placebo-controlled trial. The Copolymer 1 Multiple Sclerosis Study Group. Neurology. 1995;45(7):1268–76.

Gold R, Kappos L, Arnold DL, DEFINE Study Investigators, et al. Placebo-controlled phase 3 study of oral BG-12 for relapsing multiple sclerosis. N Engl J Med. 2012;367(12):1098–107.

Kappos L, Radue EW, O’Connor P, FREEDOMS Study Group, et al. A placebo-controlled trial of oral fingolimod in relapsing multiple sclerosis. N Engl J Med. 2010;362(5):387–401.

Calabresi PA, Radue EW, Goodin D, et al. Safety and efficacy of fingolimod in patients with relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis (FREEDOMS II): a double-blind, randomised, placebo-controlled, phase 3 trial. Lancet Neurol. 2014;13(6):545–56.

Paty DW, Li DK, UBC MS/MRI Study Group and IFNB Multiple Sclerosis Study Group. Interferon beta-lb is effective in relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis. II. MRI analysis results of a multicenter, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. 1993 [classical article]. Neurology. 2001;57(12 Suppl 5):S10–5.

Paty DW, Li DK. Interferon beta-1b is effective in relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis. II. MRI analysis results of a multicenter, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. UBC MS/MRI Study Group and the IFNB Multiple Sclerosis Study Group. Neurology. 1993;43(4):662–7.

[No authors listed]. Interferon beta-1b is effective in relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis. I. Clinical results of a multicenter, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. The IFNB Multiple Sclerosis Study Group. Neurology. 1993;43(4):655–61.

Jacobs LD, Cookfair DL, Rudick RA, et al. Intramuscular interferon beta-1a for disease progression in relapsing multiple sclerosis. The Multiple Sclerosis Collaborative Research Group (MSCRG). Ann Neurol. 1996;39(3):285–94.

[No authors listed]. Randomised double-blind placebo-controlled study of interferon beta-1a in relapsing/remitting multiple sclerosis. PRISMS (Prevention of Relapses and Disability by Interferon beta-1a Subcutaneously in Multiple Sclerosis) Study Group. Lancet. 1998;352(9139):1498–504.

O’Connor P, Wolinsky JS, Confavreux C, TEMSO Trial Group, et al. Randomized trial of oral teriflunomide for relapsing multiple sclerosis. N Engl J Med. 2011;365(14):1293–303.

Hadjigeorgiou GM, Doxani C, Miligkos M, et al. A network meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials for comparing the effectiveness and safety profile of treatments with marketing authorization for relapsing multiple sclerosis. J Clin Pharm Ther. 2013;38(6):433–9.

Hutchinson M, Fox RJ, Havrdova E, et al. Efficacy and safety of BG-12 (dimethyl fumarate) and other disease-modifying therapies for the treatment of relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis: a systematic review and mixed treatment comparison. Curr Med Res Opin. 2014;30(4):613–27.

Roskell NS, Zimovetz EA, Rycroft CE, et al. Annualized relapse rate of first-line treatments for multiple sclerosis: a meta-analysis, including indirect comparisons versus fingolimod. Curr Med Res Opin. 2012;28(5):767–80.

Klawiter EC, Cross AH, Naismith RT. The present efficacy of multiple sclerosis therapeutics: Is the new 66% just the old 33%? Neurology. 2009;73(12):984–90.

Citrome L. Relative vs. absolute measures of benefit and risk: what’s the difference? Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2010;121(2):94–102.

Francis GS. Importance of benefit-to-risk assessment for disease-modifying drugs used to treat MS. J Neurol. 2004;251(Suppl 5):v42–9.

GILENYA 0.5 mg hard capsules. Summary of product characteristics. Novartis Europharm Limited. Date of first authorisation: 17 March 2011. Date of latest renewal: 23 November 2015. Revised: 07/03/2016. Available from http://www.ema.europa.eu/docs/en_GB/document_library/EPAR_-_Product_Information/human/002202/WC500104528.pdf. Accessed 13 May 2016.

TYSABRI 300 mg concentrate for solution for infusion. Summary of product characteristics. Biogen Idec Limited. Date of first authorisation: 27th June 2006. Revised: 12/05/2016. Available from http://www.ema.europa.eu/docs/en_GB/document_library/EPAR_-_Product_Information/human/000603/WC500044686.pdf. Accessed 13 May 2016.

GILENYA (fingolimod) capsules, for oral use. Prescribing Information. Novartis AG. Initial U.S. Approval: 2010. Revised: 2/2016. Available from http://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2016/022527s018lbl.pdf. Accessed 13 May 2016.

TYSABRI (natalizumab) injection, for intravenous use. Prescribing Information. Biogen Idec Inc. Initial U.S. Approval: 2004. Revised: 2/2012. Available from http://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2012/125104s0576lbl.pdf. Accessed 13 May 2016.

Tuttle AH, Tohyama S, Ramsay T, et al. Increasing placebo responses over time in U.S. clinical trials of neuropathic pain. Pain. 2015;156(12):2616–26.

Caucheteux N, Maarouf A, Genevray M, et al. Criteria improving multiple sclerosis diagnosis at the first MRI. J Neurol. 2015;262(4):979–87.

Vermersch P, Czlonkowska A, Grimaldi LM, TENERE Trial Group, et al. Teriflunomide versus subcutaneous interferon beta-1a in patients with relapsing multiple sclerosis: a randomised, controlled phase 3 trial. Mult Scler. 2014;20(6):705–16.

Oh J, O’Connor PW. Teriflunomide in the treatment of multiple sclerosis: current evidence and future prospects. Ther Adv Neurol Disord. 2014;7(5):239–52.

Rawlins M. De testimonio: on the evidence for decisions about the use of therapeutic interventions. Lancet. 2008;372(9656):2152–61.

Hammad TA, Neyarapally GA, Pinheiro SP, et al. Reporting of meta-analyses of randomized controlled trials with a focus on drug safety: an empirical assessment. Clin Trials. 2013;10(3):389–97.

Hammad TA, Neyarapally GA, Iyasu S, et al. The future of population-based postmarket drug risk assessment: a regulator’s perspective. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2013;94(3):349–58.

Sheremata W, Brown AD, Rammohan KW. Dimethyl fumarate for treating relapsing multiple sclerosis. Expert Opin Drug Saf. 2015;14(1):161–70.

Bloomgren G, Richman S, Hotermans C, et al. Risk of natalizumab-associated progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy. N Engl J Med. 2012;366(20):1870–80.

European Medicines Agency. New recommendations to minimise risks of the rare brain infection PML and a type of skin cancer with Gilenya [Press Release: 18/12/2015]. Available from http://www.ema.europa.eu/ema/index.jsp?curl=pages/news_and_events/news/2015/12/news_detail_002447.jsp&mid=WC0b01ac058004d5c1#1. Accessed 13 May 2016.

European Medicines Agency. Updated recommendations to minimise the risk of the rare brain infection PML with Tecfidera [Press Release: 23/10/2015]. Available from http://www.ema.europa.eu/ema/index.jsp?curl=pages/news_and_events/news/2015/10/news_detail_002423.jsp&mid=WC0b01ac058004d5c1. Accessed 13 May 2016.

Faulkner M. Risk of progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy in patients with multiple sclerosis. Expert Opin Drug Saf. 2015;14(11):1737–48.

McGuigan C, Craner M, Guadagno J, et al. Stratification and monitoring of natalizumab-associated progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy risk: recommendations from an expert group. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2016;87(2):117–25.

Nieuwkamp DJ, Murk JL, van Oosten BW, PML in Dutch MS Patients Consortium, et al. PML in a patient without severe lymphocytopenia receiving dimethyl fumarate. N Engl J Med. 2015;372(15):1474–6.

Arkema EV, van Vollenhoven RF, Askling J, ARTIS Study Group. Incidence of progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy in patients with rheumatoid arthritis: a national population-based study. Ann Rheum Dis. 2012;71(11):1865–7.

Gilenyaworldwatch.com. Gilenya World Watch; 2016. [online] Available from http://gilenyaworldwatch.com/English.html. Accessed 13 May 2016.

Plavina T, Subramanyam M, Bloomgren G, et al. Anti-JC virus antibody levels in serum or plasma further define risk of natalizumab-associated progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy. Ann Neurol. 2014;76(6):802–12. doi:10.1002/ana.24286 [Epub 2014 Oct 24].

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Biogen Idec Portugal for the supplied data (population exposure and number of PML cases reported with DMF).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

Diogo Mendes declares that he has no conflict of interest. Carlos Alves declares that he has no conflict of interest. Francisco Batel-Marques declares that he has no conflict of interest.

Funding

This study was not financially supported by any institution.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Mendes, D., Alves, C. & Batel-Marques, F. Benefit–Risk of Therapies for Relapsing–Remitting Multiple Sclerosis: Testing the Number Needed to Treat to Benefit (NNTB), Number Needed to Treat to Harm (NNTH) and the Likelihood to be Helped or Harmed (LHH): A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. CNS Drugs 30, 909–929 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40263-016-0377-9

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40263-016-0377-9