Abstract

Background

Ropivacaine is frequently used in spinal anesthesia but the relationship between plasma concentrations and sensory block level remains unknown.

Objective

The aim of this study was to assess the relationship between plasma ropivacaine concentrations and effects during spinal anesthesia.

Methods

Sixty patients aged between 18 and 82 years were included in this study after providing written informed consent. Patients were randomly assigned to receive intrathecal administration of ropivacaine 15, 20 or 25 mg. Blood samples were drawn to determine ropivacaine concentrations, and sensory blockade was assessed using pinprick testing. Ropivacaine plasma concentrations and sensory block level were analyzed using a nonlinear mixed-effects modeling approach with Monolix 4.2.2. Uncertainty of parameters was estimated by bootstrapping.

Results

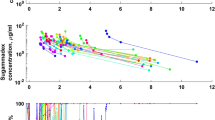

Overall, 216 plasma ropivacaine values and 407 sensory block-related data were available for pharmacokinetic-pharmacodynamic (PK-PD) model evaluation. A two-compartment open model connected to a spinal compartment was selected to describe the PKs of ropivacaine. Sensory block modeling was performed using a sigmoid E max model assuming an equilibration delay between the amount in the depot or spinal compartment and at the effect site. Using multiple linear regression analysis, we were able to demonstrate the importance of dose, age and weight as major predictors of sensory block-level kinetics.

Conclusions

This first population PK-PD model for ropivacaine in spinal anesthesia confirms the relationship between plasma ropivacaine concentrations and effect. We also clarify the relationship between the spread of sensory block level and dose, age and, for the first time, weight.

Study Registration

This study was approved by the Reims University Hospital Ethics Committee (protocol: PHRC-2005; registered at Agence Nationale de Sécurité du Médicament et des Produits de Santé ANSM: D60890). This was an open, prospective, monocentric study conducted in the University Hospital of Reims (France).

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Simpson D, Curran MP, Oldfield V, Keating GM. Ropivacaine: a review of its use in regional anaesthesia and acute pain management. Drugs. 2005;65:2675–717.

Thomas JM, Schug SA. Recent advances in the pharmacokinetics of local anaesthetics. Long-acting amide enantiomers and continuous infusions. Clin Pharmacokinet. 1999;36:67–83.

Greene NM. Distribution of local anesthetic solutions within the subarachnoid space. Anesth Analg. 1985;64:715–30.

Malinovsky JM, Charles F, Kick O, Lepage JY, Malinge M, Cozian A, et al. Intrathecal anesthesia: ropivacaine versus bupivacaine. Anesth Analg. 2000;91:1457–60.

Hocking G, Wildsmith JAW. Intrathecal drug spread. Br J Anaesth. 2004;93:568–78.

Khaw KS, Ngan Kee WD, Wong EL, Liu JY, Chung R. Spinal ropivacaine for cesarean section: a dose-finding study. Anesthesiology. 2001;95:1346–50.

Carpenter RL, Hogan QH, Liu SS, Crane B, Moore J. Lumbosacral cerebrospinal fluid volume is the primary determinant of sensory block extent and duration during spinal anesthesia. Anesthesiology. 1998;89:24–9.

Hogan QH, Prost R, Kulier A, Taylor ML, Liu S, Mark L. Magnetic resonance imaging of cerebrospinal fluid volume and the influence of body habitus and abdominal pressure. Anesthesiology. 1996;84:1341–9.

Djerada Z, Fournet-Fayard A, Gozalo C, Lelarge C, Lamiable D, Millart H, et al. Population pharmacokinetics of nefopam in elderly, with or without renal impairment, and its link to treatment response. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2014;77:1027–38.

Bonate PL. Pharmacokinetic-pharmacodynamic modeling and simulation. 2nd ed. New York: Springer-Verlag New York Inc.; 2011.

Gaudreault F. Pharmacométrie de la ropivacaïne suivant l’anesthésie locorégionale chez les patients orthopédiques: caractérisation de l’intensité et de la durée du bloc sensitif. . 2014. https://papyrus.bib.umontreal.ca/xmlui/handle/1866/10331. Accessed 31 Jul 2016.

Ollier E, Heritier F, Bonnet C, Hodin S, Beauchesne B, Molliex S, et al. Population pharmacokinetic model of free and total ropivacaine after transversus abdominis plane nerve block in patients undergoing liver resection. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2015;80:67–74.

Gaudreault F, Drolet P, Fallaha M, Varin F. Modeling the anesthetic effect of ropivacaine after a femoral nerve block in orthopedic patients: a population pharmacokinetic-pharmacodynamic analysis. Anesthesiology. 2015;122:1010–20.

Gambús PL, Trocóniz IF. Pharmacokinetic-pharmacodynamic modelling in anaesthesia. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2015;79:72–84.

Choquette A, Troncy E, Guillot M, Varin F, del Castillo JRE. Pharmacokinetics of lidocaine hydrochloride administered with or without adrenaline for the paravertebral brachial plexus block in dogs. PLoS One. 2017;12:e0169745.

Hoizey G, Lamiable D, Robinet A, Ludot H, Malinovsky J-M, Kaltenbach ML, et al. Sensitive bioassay of bupivacaine in human plasma by liquid-chromatography-ion trap mass spectrometry. J Pharm Biomed Anal. 2005;39:587–92.

US Food and Drug Administration. Guidance for industry. Bioanalytical method validation; May 2001. http://www.fda.gov/downloads/Drugs/Guidances/ucm070107.pdf. Accessed 1 July 2010.

Djerada Z, Feliu C, Tournois C, Vautier D, Binet L, Robinet A, et al. Validation of a fast method for quantitative analysis of elvitegravir, raltegravir, maraviroc, etravirine, tenofovir, boceprevir and 10 other antiretroviral agents in human plasma samples with a new UPLC-MS/MS technology. J Pharm Biomed Anal. 2013;86:100–11.

Djerada Z, Peyret H, Dukic S, Millart H. Extracellular NAADP affords cardioprotection against ischemia and reperfusion injury and involves the P2Y11-like receptor. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2013;434:428–33.

Lavielle M, Mentré F. Estimation of population pharmacokinetic parameters of saquinavir in HIV patients with the MONOLIX software. J Pharmacokinet Pharmacodyn. 2007;34:229–49.

Mould DR, Upton RN. Basic concepts in population modeling, simulation, and model-based drug development-part 2: introduction to pharmacokinetic modeling methods. CPT Pharmacomet Syst Pharmacol. 2013;2:e38.

Lixoft. Documentation. http://www.lixoft.eu/monolix/documentation/. Accessed 3 June 2013.

Lavielle M. Mixed effects models for the population approach: models, tasks, methods and tools. Boca Roton: CRC Press; 2014.

Schnider TW, Minto CF, Bruckert H, Mandema JW. Population pharmacodynamic modeling and covariate detection for central neural blockade. Anesthesiology. 1996;85:502–12.

Mandema JW, Verotta D, Sheiner LB. Building population pharmacokinetic–pharmacodynamic models. I. Models for covariate effects. J Pharmacokinet Biopharm. 1992;20:511–28.

Wald A. Tests of statistical hypotheses concerning several parameters when the number of observations is large. Trans Am Math Soc. 1943;54:426–82.

Comets E, Brendel K, Mentré F. Computing normalised prediction distribution errors to evaluate nonlinear mixed-effect models: the npde add-on package for R. Comput Methods Programs Biomed. 2008;90:154–66.

Lavielle M, Ribba B. Enhanced method for diagnosing pharmacometric models: random sampling from conditional distributions. Pharm Res. 2016;33:2979–88.

Bergstrand M, Hooker AC, Wallin JE, Karlsson MO. Prediction-corrected visual predictive checks for diagnosing nonlinear mixed-effects models. AAPS J. 2011;13:143–51.

Parke J, Holford NH, Charles BG. A procedure for generating bootstrap samples for the validation of nonlinear mixed-effects population models. Comput Methods Programs Biomed. 1999;59:19–29.

Ette EI. Stability and performance of a population pharmacokinetic model. J Clin Pharmacol. 1997;37:486–95.

Sheiner LB, Beal SL. Evaluation of methods for estimating population pharmacokinetic parameters. II. Biexponential model and experimental pharmacokinetic data. J Pharmacokinet Biopharm. 1981;9:635–51.

Gabrielsson J, Weiner D. Pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic data analysis: concepts and applications. 4th ed. Stockholm: Swedish Pharmaceutical Press; 2007.

Savic RM, Jonker DM, Kerbusch T, Karlsson MO. Implementation of a transit compartment model for describing drug absorption in pharmacokinetic studies. J Pharmacokinet Pharmacodyn. 2007;34:711–26.

Kopacz DJ, Emanuelsson BM, Thompson GE, Carpenter RL, Stephenson CA. Pharmacokinetics of ropivacaine and bupivacaine for bilateral intercostal blockade in healthy male volunteers. Anesthesiology. 1994;81:1139–48.

Simon MJG, Veering BT, Vletter AA, Stienstra R, van Kleef JW, Burm AGL. The effect of age on the systemic absorption and systemic disposition of ropivacaine after epidural administration. Anesth Analg. 2006;102:276–82.

Olofsen E, Burm AGL, Simon MJG, Veering BT, van Kleef JW, Dahan A. Population pharmacokinetic-pharmacodynamic modeling of epidural anesthesia. Anesthesiology. 2008;109:664–74.

Lee A, Fagan D, Lamont M, Tucker GT, Halldin M, Scott DB. Disposition kinetics of ropivacaine in humans. Anesth Analg. 1989;69:736–8.

Burm AG. Clinical pharmacokinetics of epidural and spinal anaesthesia. Clin Pharmacokinet. 1989;16:283–311.

Stanski DR. Pharmacodynamic modeling of anesthetic EEG drug effects. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol. 1992;32:423–47.

Jeleazcov C, Lavielle M, Schüttler J, Ihmsen H. Pharmacodynamic response modelling of arterial blood pressure in adult volunteers during propofol anaesthesia. Br J Anaesth. 2015;115:213–26.

Ngan Kee WD, Ng FF, Khaw KS, Lee A, Gin T. Determination and comparison of graded dose-response curves for epidural bupivacaine and ropivacaine for analgesia in laboring nulliparous women. Anesthesiology. 2010;113:445–53.

Shafer SL, Eisenach JC, Hood DD, Tong C. Cerebrospinal fluid pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of intrathecal neostigmine methylsulfate in humans. Anesthesiology. 1998;89:1074–88.

Jacobs JM, Love S. Qualitative and quantitative morphology of human sural nerve at different ages. Brain J Neurol. 1985;108(Pt 4):897–924.

Dorfman LJ, Bosley TM. Age-related changes in peripheral and central nerve conduction in man. Neurology. 1979;29:38–44.

Cameron AE, Arnold RW, Ghorisa MW, Jamieson V. Spinal analgesia using bupivacaine 0.5% plain. Variation in the extent of the block with patient age. Anaesthesia. 1981;36:318–22.

Racle JP, Benkhadra A, Poy JY, Gleizal B. Spinal analgesia with hyperbaric bupivacaine: influence of age. Br J Anaesth. 1988;60:508–14.

Veering BT, Burm AG, Spierdijk J. Spinal anaesthesia with hyperbaric bupivacaine. Effects of age on neural blockade and pharmacokinetics. Br J Anaesth. 1988;60:187–94.

Hirabayashi Y, Shimizu R, Saitoh K, Fukuda H. Spread of subarachnoid hyperbaric amethocaine in adolescents. Br J Anaesth. 1995;74:41–5.

Sakura S, Imamachi N, Toyota K, Shono A, Saito Y. Spinal anesthesia with tetracaine in 7.5 or 0.75% glucose in adolescents and adults. Anesth Analg. 2001;93:77–81.

Ben-David B, Levin H, Solomon E, Admoni H, Vaida S. Spinal bupivacaine in ambulatory surgery: the effect of saline dilution. Anesth Analg. 1996;83:716–20.

Povey HM, Olsen PA, Pihl H, Jacobsen J. High dose spinal anaesthesia with glucose free 0.5% bupivacaine 25 and 30 mg. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand. 1995;39:457–61.

McDonald SB, Liu SS, Kopacz DJ, Stephenson CA. Hyperbaric spinal ropivacaine: a comparison to bupivacaine in volunteers. Anesthesiology. 1999;90:971–7.

De Simone CA, Leighton BL, Norris MC. Spinal anesthesia for cesarean delivery. A comparison of two doses of hyperbaric bupivacaine. Reg Anesth. 1995;20:90–4.

Acknowledgments

We thank medical staff who collected the data of the study. We thank laboratory staff of pharmacology that performed plasma determination. We thank Lixoft Company to provide us the academic user license. We thank Prof Nick Holford to provide us wings usable with Monolix software.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Z.D. designed the study, study execution and data acquisition, developed and implemented the PK/PD models in MONOLIX, data analysis and interpretation, graphical representation, and wrote the first draft of the manuscript. C.F., Y.C., DG: data acquisition, data interpretation, graphical representation, and revised critically the manuscript for content and gave final approval to the manuscript version submitted for publication. F.S., P.G., B.C., O.F. performed the volunteer recruitment, data interpretation, and revised critically the manuscript for content and gave final approval to the manuscript version submitted for publication. J.J.M.: designed the study, study execution and data acquisition, performed recruitment, data analysis and interpretation, revised critically the manuscript for content and gave final approval to the manuscript version submitted for publication.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Funding

This study was funded by the Regional Clinical Research Program of Reims University Hospital, in 2004 (PHRC 2005).

Conflict of interest

Z.D., C.F., Y.C., D.G, F.S., P.G., B.C., O.F., J.J.M. declare no financial relationships with any organisations that might have an interest in the submitted work; no other relationships or activities that could appear to have influenced the submitted work.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

40262_2017_617_MOESM1_ESM.jpg

Electronic Supplementary Fig. 1 Diagnostic plots. Population (blue dot) or individual (black circle) weighted residuals (PWRES or IWRES) versus time of ropivacaine concentration (a) and sensory block level (b), PWRES or IWRES versus respective predictions of ropivacaine concentration (c) and sensory block level (d)

40262_2017_617_MOESM2_ESM.jpg

Electronic Supplementary Fig. 2 Diagnostic plots. Observed ropivacaine concentrations versus population-predicted ropivacaine concentrations (a). Observed sensory block level versus population-predicted sensory block level (b)

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Djerada, Z., Feliu, C., Cazaubon, Y. et al. Population Pharmacokinetic-Pharmacodynamic Modeling of Ropivacaine in Spinal Anesthesia. Clin Pharmacokinet 57, 1135–1147 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40262-017-0617-2

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40262-017-0617-2