Abstract

Heart failure (HF) is a common cause of cardiovascular mortality and morbidity. Despite advances in treatment, the prognosis remains poor. Sodium-glucose co-transporter 2 (SGLT-2) inhibitors decrease HF events by 27–39% in high-risk patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM). Moreover, the DAPA-HF and EMPEROR-Reduced studies randomized patients with HF with reduced ejection fraction (HFrEF) with or without diabetes mellitus to receive guideline-directed medical therapy versus guideline-directed medical therapy plus an SGLT-2 inhibitor. Both studies showed the benefits of SGLT-2 inhibitors. In addition, SGLT-2 inhibitors have shown improvement according to the EMPEROR-Preserved study of HF with preserved ejection fraction (HFpEF). Therefore, a panel of cardiology experts from the Egyptian Atherosclerosis and Vascular Biology Association (EAVA) revised the literature for SGLT-2 inhibitors in HF, along with the recommended indications and contraindications, and this article presents their consensus on the topic. The panel concluded that SGLT-2 inhibitors have significantly benefited patients with chronic HFrEF, as indicated through the DAPA-HF and EMPEROR-Reduced trials. The panel recommended early use of dapagliflozin 10 mg or empagliflozin 10 mg in patients with symptomatic chronic HFrEF, whether diabetic or non-diabetic, to ameliorate HF hospitalization rate, mortality, symptoms, and decline in renal function.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Sodium-glucose co-transporter 2 (SGLT-2) inhibitors initially investigated for their glucose-lowering capability have shown significant benefit in chronic heart failure with reduced ejection fraction (HFrEF), as indicated through the DAPA-HF and EMPEROR-Reduced trials. |

The panel of experts recommends the early use of dapagliflozin 10 mg or empagliflozin 10 mg in patients with symptomatic chronic HFrEF, whether the patient is diabetic or non-diabetic, to ameliorate HF hospitalization rate, death, symptoms, and decline in renal function. |

1 Introduction

Heart failure (HF) is a common cause of cardiovascular (CV) mortality and morbidity [1, 2], and despite advances in treatment, the prognosis remains poor [3]. CV diseases (CVD) have been the leading cause of premature death in Egypt since the 1990s [4], and in 2017, CVD accounted for 46.2% of overall mortality from non-communicable diseases in Egypt [5]. HF poses a significant and growing public health burden because of the success of the healthcare system’s endeavors in improving the survival of those with coronary events [6].

Moreover, CVD accounted for 33% of the total daily-adjusted life-years (DALYs) lost. In line with global efforts, there is a rising trend in health care expenditure in Egypt. Comprehensive studies evaluating the prevalence, mortality, and cost-of-illness (COI) of HF are generally lacking in the Middle East and Egypt. In Middle Eastern countries, with the absence of health insurance claims databases that can quantify the national cost of HF, the interview method indicated that HF is a costly disease, with inpatient admissions being the key cost driver [6].

For decades, diabetes mellitus (DM) medications were established solely for their ability to lower the blood glucose level; however, little was understood about their long-term CV outcomes. Since 2008, it has become mandatory that all new antihyperglycemic medications be evaluated for CV safety because there have been reports of a CV risk signal with particular pharmacological products (tolbutamide, muraglitazar, and rosiglitazone) or in the context of rigorous glycemic management in specific patient groups (the ACCORD trial) [7]. Therefore, over the last decade, dipeptidyl peptidase-4 inhibitors (DPP-4i), glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonists (GLP-1RAs), and sodium-glucose co-transporter 2 (SGLT-2) inhibitors have been investigated in CV outcome trials (CVOTs). These CVOTs have shown that some of these newer medications are well tolerated in relation to CV risk, and improve outcomes. Therefore, a country-specific (Egypt) task force was gathered to develop an explicit, evidence-based consensus for adopting SGLT-2 inhibitors in patients with HF with or without DM. This article illustrates the recommendations of this expert committee.

2 Clinical Background of Heart Failure (HF)

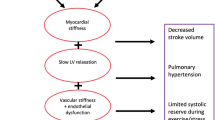

The scientific community classified HF into three categories: HF with reduced ejection fraction (HFrEF), HF with preserved ejection fraction (HFpEF), or HF with mid-range ejection fraction (HFmrEF). HFrEF is also known as systolic HF, where the heart has a reduced pump function because of its inability to contract, and it manifested echographically by reduced left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) ≤ 40%. On the other hand, HFpEF is regularly known as diastolic dysfunction due to impaired relaxation and filling of the cardiac chambers, with LVEF of at least 50%. Regardless of the classification, HF results in fatigue, shortness of breath (SOB), and fluid retention. Being a chronic progressive disease, it has a pattern of compensation–decompensation cycles with periods of stability, followed by acute decompensation with all its consequences. Finally, the novel nosographic entity HFmrEF represents a group with diverse clinical features that mimics HFrEF at times, HFpEF at other times, and a distinct phenotype at other times [8].

3 Management of HF: The Current Standard of Care

The currently adopted standard of care for people with symptomatic HFrEF (stage C: New York Heart Association [NYHA] classification of heart failure class I–IV) includes both medications and supportive devices [8, 9].

Diuretics remain an essential pillar in the management of congestion in HFrEF. The mortality benefits of β-blockers and renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system (RAAS) inhibitors (including angiotensin-converting enzyme [ACE] inhibitors, angiotensin receptor blockers [ARBs], and direct renin inhibitors), as well as mineralocorticoid receptor antagonists (MRAs), are significant. More recently, a combination of sacubitril/valsartan and ivabradine therapy has been included in HF guidelines for their capability to lessen morbidity and mortality in specific subgroups of patients [8]. Three guidelines, namely the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE), the Canadian Cardiovascular Society (CCS) guidelines, and the Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network (SIGN) guidelines, included algorithms with potential for the use of combination therapy with sacubitril/valsartan and ivabradine in the management of HF [10,11,12]; however, no evidence supported this [13].

Patients with HFpEF comprise about half of the HF population. There is a need for therapies that improve mortality and morbidity. The main treatment goals are hypertension control and relief from symptoms of volume overload by diuretics. In a specific subset of patients, MRA therapy may be considered to decrease hospitalizations [14]. Moreover, angiotensin receptor II blocker–neprilysin inhibitor (ARNI) treatment failed to improve survival or reduce hospitalization for HF when compared with valsartan in the PARAGON-HF trial [15].

4 Refining the Goals of Therapy

5 The Beginning of a New Era for People with HF: Insights from the Available Literature

5.1 Lessons from Cardiovascular Outcomes Trials (CVOTs): Sodium-Glucose Co-Transporter 2 (SGLT-2) Inhibitors and HF in Diabetes Mellitus (DM)

The results of CVOTs have shown that SGLT-2 inhibitors are well tolerated in terms of CV risk and can improve patients’ CV outcomes. Over the years, many CVOTs have been conducted and have studied different molecules. Some of these CVOTs are as follows.

-

Empagliflozin Cardiovascular Outcome Event Trial in Type 2 DM Patients Removing Excess Glucose (EMPA-REG OUTCOME) [16].

-

Canagliflozin Cardiovascular Assessment Study (CANVAS) program, which combined data from two trials (CANVAS and CANVAS-R) [17].

-

Canagliflozin and Renal Events in Diabetes with Established Nephropathy Clinical Evaluation (CREDENCE) [18].

-

Dapagliflozin Effect on Cardiovascular Events–Thrombosis in Myocardial Infarction 58 (DECLARE–TIMI 58) [19].

-

Evaluation of Ertugliflozin Efficacy and Safety Cardiovascular (VERTIS-CV) [20, 21].

As concluded from all these trials, SGLT-2 inhibitors have been proven to have beneficial effects in reducing both major adverse CV events (MACE) as well as hospitalizations for HF, and a few of these drugs have also reduced CV mortality (i.e., empagliflozin [16] and canagliflozin [18]). In trials with SGLT-2 inhibitors (empagliflozin, canagliflozin, and dapagliflozin) in patients with type 2 DM (T2DM), a reduction in HF hospitalizations is a consistent finding [22]. In three CVOTs and a renal outcomes trial, they have been shown to decrease HF hospitalizations by 27–39% in high-risk patients with T2DM [18].

The reduction in the need for hospitalization for HF was observed early after randomization, which raised the possibility of different mechanisms of action [23,24,25,26,27]. SGLT-2 inhibitors have a diuretic effect with consequent hemodynamic actions. Moreover, there are other proposed mechanisms for their effect on HF, such as their effects on the metabolism of the myocardium, vascular function, ion transport, adipokines, and fibrosis [23,24,25,26,27]. Preservation of renal function is an added benefit. All these actions are beneficial in HF, including in patients without DM [22, 28].

The results of the SOLOIST-WHF trial, a multicenter, double-blind trial in which 1222 patients with T2DM were hospitalized for worsening HF, have recently been published. The study compared sotagliflozin with placebo for their effects on the total number of deaths from CV causes and hospitalizations and urgent visits for HF as a primary endpoint, which were lower in the sotagliflozin group than in the placebo group (51.0 vs. 76.3; hazard ratio [HR] 0.67, confidence interval [CI] 0.52–0.85; p < 0.001). The SOLOIST-WHF trial showed that the initiation of SGLT-2 inhibitors in the acute stage of HF before or shortly after discharge is effective and well tolerated in those with HFrEF and HFpEF [29].

5.2 SGLT-2 Inhibitors for HF in Patients Without DM

The positive results reported in CVOTs encouraged researchers to investigate the role of SGLT-2 inhibitors for HF in patients without DM. Two randomized studies, namely the ‘Dapagliflozin and Prevention of Adverse Outcomes in Heart Failure’ (DAPA-HF) trial and the ‘Empagliflozin Outcome Trial in Patients with Chronic Heart Failure and a Reduced Ejection Fraction’ (EMPEROR-Reduced) study, addressed this research topic. These two studies randomized patients (4744 patients in DAPA-HF and 3730 patients in EMPEROR-Reduced) with HFrEF, with or without DM, to receive guideline-directed medical therapy versus guideline-directed medical therapy plus an SGLT-2 inhibitor [30, 31].

The DAPA-HF trial concluded that among patients with HFrEF, the risk of worsening HF or death from CV causes was lower among the dapagliflozin group than the placebo group, regardless of the presence or absence of DM. After the follow-up period, the primary outcome (the composite of CV mortality or worsening of HF) was significantly (p < 0.001) lower in the dapagliflozin group (16.3%) than in the placebo group (21.2%; HR 0.74, 95% CI 0.65–0.85), which was consistent in those with or without DM. Moreover, fewer symptoms were experienced in the dapagliflozin group than in the placebo group between baseline and month 8, as indicated by the total symptom score on the Kansas City Cardiomyopathy Questionnaire. In addition, the incidence of the prespecified renal composite outcome did not differ between groups (HR 0.71, 95% CI 0.44–1.16) [30]. This resulted in the US FDA approving dapagliflozin in May 2020 for reducing the risk of CV mortality and hospitalization for patients with HFrEF [32].

Furthermore, the non-significant improvement of renal outcomes seen in the DAPA-HF trial is not indicative of a less renal protective effect of dapagliflozin, as this has, without a doubt, been demonstrated in the ‘Dapagliflozin in Patients with Chronic Kidney Disease’ (DAPA-CKD) study [33]. The DAPA-CKD study concluded that among patients with CKD, regardless of the presence or absence of DM, the combined endpoint of decline in the estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) of at least 50%, end-stage kidney disease, or death from renal or CV causes was significantly lower with dapagliflozin than placebo [33].

The EMPEROR-Reduced trial compared empagliflozin with placebo for the treatment of patients with HFrEF with or without DM. The results of this trial solidified the role of SGLT-2 inhibitors in HFrEF for patients without DM. The study concluded that, among HF patients, those in the empagliflozin group had a lower risk of CV mortality or hospitalization due to HF than those in the placebo group, regardless of whether they had DM or not. The primary composite outcome of CV mortality or hospitalization for HF was significantly (p < 0.001) reduced in the empagliflozin group (HR 0.75, 95% CI 0.65–0.86). This effect was consistent across the prespecified subgroups, including those with or without DM. In addition, the decline in the eGFR was significantly (p < 0.001) slower in the empagliflozin group than in the placebo group [31]. The CV mortality and all-cause death rates, which were not met in the EMPEROR-Reduced trial, are not of concern as the EMPA-REG trial has shown a significant benefit in both endpoints using empagliflozin [16].

Thus, it can be concluded from the DAPA-HF and EMPEROR-Reduced trials that dapagliflozin and empagliflozin showed a significant reduction in HF failure hospitalizations (both trials), CV mortality (dapagliflozin trial), all-cause mortality (dapagliflozin trial), improvement of symptoms (both trials), renal protection (empagliflozin trial), and can be safely administered in both diabetic and non-diabetic patients (both trials).

All of this led the Heart Failure Association of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC-HFA) to update their guidelines on SGLT-2 inhibitors in HF, with a recommendation to use dapagliflozin or empagliflozin to lessen the combined risk of HF hospitalizations and CV mortality in symptomatic patients with HFrEF regardless of the presence of DM [34]. More recently, this recommendation was surpassed by the ESC-HFA guideline recommendation for the addition of SGLT-2 inhibitors, namely dapagliflozin and empagliflozin for all patients with HFrEF already receiving an ACE inhibitor/ARNI, β-blocker, or MRA, regardless of whether or not they have DM [35].

5.3 SGLT-2 Inhibitors for HF with Preserved Ejection Fraction (HFpEF)

Both the DAPA-HF and EMPEROR-Reduced trials enrolled patients with HFrEF, but research studies are underway to determine whether SGLT-2 inhibitors can play a much-needed role in patients with HFpEF. A subgroup analysis of the CANVAS program suggested that canagliflozin may reduce HFpEF hospitalizations or mortality (HR 0.83, 95% CI 0.55–1.25). Nevertheless, the results were not statistically significant because the study was not designed to investigate that difference [17]. Another subgroup analysis of HFpEF patients in the DECLARE-TIMI 58 study also found a signal for reduced risk of HF hospitalizations (HR 0.74, 95% CI 0.48–1.14) but not for CV mortality (HR 1.44, 95% CI 0.83–2.49). These results should be reported with caution as the study was not powered to detect that difference from the start [19, 22]. The DELIVER trial (NCT03619213) with dapagliflozin is studying similar outcomes as the DAPA-HF trial but in patients with HFpEF rather than HFrEF [36]. Additionally, the EMPEROR-Preserved trial, which compared empagliflozin with placebo in patients with HFpEF, showed a significant reduction in the combined primary endpoint of HF hospitalizations and CV mortality [37, 38].

In 2020, the European Society of Cardiology (ESC), with a contribution from the Heart Failure Association (HFA), developed a position paper on the role of SGLT-2 inhibitors in the treatment of HF. They stated that SGLT-2 inhibitors should be used as soon as possible for all patients with HFrEF, in conjunction with or in addition to β-blockers, ACE inhibitors/ARBs, and MRAs, and sacubitril/valsartan. In addition, the significant impact on CV and overall mortality, plus the significant reduction in hospitalizations for HF, suggest dapagliflozin is the SGLT-2 inhibitor of choice in patients with HFrEF. Therefore, its initiation should be pursued in all cases, regardless of background therapy, at any stage of the disease timeline (the earlier the better), as suggested by the 2021 ESC-HFA guidelines [34, 35, 39].

6 Practical Considerations for the Use of SGLT-2 Inhibitors in HF

6.1 Check for Renal Status

Several trials have shown the beneficial renal outcomes associated with the administration of SGLT-2 inhibitors, however we should adhere to the evidence. The DAPA-HF trial excluded patients with eGFR below 30 mL/min/1.73 m2, while the EMPEROR-Reduced trial had a cut-off point of 20 mL/min/1.73m2. It should be noted that that there is an initial reduction in the eGFR, but the long-term benefits outweigh this phenomenon.

6.2 Adjustment of Other Medications

When managing HFrEF, polypharmacy is always a barrier to patient compliance and sometimes induces drug–drug interactions. For stable patients with HFrEF, the need to adjust background loop diuretics should be individualized based on evaluating the congestive symptoms. DAPA-HF had no routine protocolized adjustment of loop diuretics when initiating study therapy, and only ≈ 7% of subjects experienced volume depletion, with no significant difference versus placebo. We propose that HFrEF patients in the outpatient setting who receive a daily dose of more than 40 mg of frusemide or equivalent from other loop diuretics should be followed-up more vigilantly for volume depletion, as seen from the subgroup analysis in DAPA-HF. In addition, the benefit of SGLT-2 inhibitors has been demonstrated to be independent of MRA [40,41,42], and also independent of and in addition to sacubutril-valsartan [40, 43], as shown in the DAPA-HF and the EMPEROR-Reduced trials [30, 31].

6.3 A Multidisciplinary Approach

The multidisciplinary approach to care is a disease management program encompassing a wide range of organized treatment regimens and interventions for patients with chronic diseases. Because HF causes multisystem malfunction, it appears logical to use a multidisciplinary approach, recognizing this complexity and allowing different aspects to be handled by the most qualified healthcare experts, such as diabetologists and nephrologists, and therefore enabling patients to receive the appropriate care from the appropriate person at the appropriate time [44].

6.4 Following-Up of Patients for Safety Issues Related to SGLT-2 Inhibitors

The serious but uncommon hazards of diabetic ketoacidosis (DKA) and necrotizing fasciitis of the perineum are some of the possible concerns of SGLT-2 inhibitors, while volume depletion and genitourinary infection are two additional concerns. The DAPA-HF trial [29] showed that there was no risk for hypoglycemia. Patients should be taught to cease taking SGLT-2 inhibitors temporarily if they are sick and have reduced oral intake, and to decrease the risk of DKA and acute renal damage. SGLT-2 inhibitors should also not be administered to patients who are hypovolemic or hypotensive. Furthermore, if SGLT-2 inhibitors are taken, loop and/or thiazide diuretic doses may need to be reduced [45].

6.5 SGLT-2 Inhibitor Eligibility and Generalizability in HF with Reduced Ejection Fraction in the Real World

The results of the Get With the Guidelines-Heart Failure (GWTG-HF) registry (2014–2019) in the United States showed that four of five patients with HFrEF (with or without T2DM) would be candidates for dapagliflozin treatment, indicating its broad applicability [46]. According to the main criteria of the DAPA-HF trial, about half of the HFrEF group would be eligible for dapagliflozin, as shown in other real-world research. An eGFR of <30 mL/min/1.73 m2 was the primary cause for ineligibility [47]. A recent real-world study found that 45% of HFrEF patients would be candidates for SGLT-2 inhibitor treatment, demonstrating the drug’s broad generalizability in clinical practice [48].

7 Future Directions

We look forward to upcoming trials for SGLT-2 inhibitors in the management of acute HF and post-myocardial infarction. In addition, a real-world local study is recommended.

8 Conclusions

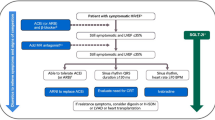

SGLT-2 inhibitors initially investigated for their glucose-lowering capability have shown a significant benefit in chronic HFrEF, as indicated through the DAPA-HF and EMPEROR-Reduced trials. We recommend early use of dapagliflozin 10 mg or empagliflozin 10 mg in patients with symptomatic chronic HFrEF, whether the patient is diabetic or non-diabetic, to reduce the heart failure hospitalization rate, deaths, symptoms, and decline in renal function (see Fig. 1). In addition, according to the EMPEROR-Preserved trial, SGLT-2 inhibitors may be considered for HFpEF.

References

Koudstaal S, Pujades-Rodriguez M, Denaxas S, et al. Prognostic burden of heart failure recorded in primary care, acute hospital admissions, or both: a population-based linked electronic health record cohort study in 2.1 million people. Eur J Heart Fail. 2017;19:1119–27.

Shah AD, Langenberg C, Rapsomaniki E, et al. Type 2 diabetes and incidence of cardiovascular diseases: a cohort study in 1.9 million people. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2015;3:105–13.

Jones NR, Roalfe AK, Adoki I, et al. Survival of patients with chronic heart failure in the community: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur J Heart Fail. 2019;21:1306–25.

Global health estimates 2019 summary tables: Egypt estimated deaths by cause, sex and WHO Member State 2019. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2019. https://www.who.int/data/gho/data/themes/mortality-and-global-health-estimates/ghe-leading-causes-of-death. Accessed 2 Oct 2021.

Hassanin A, Hassanein M, Bendary A, et al. Demographics, clinical characteristics, and outcomes among hospitalized heart failure patients across different regions of Egypt. Egypt Heart J. 2020;72:49. https://doi.org/10.1186/s43044-020-00082-0.

AlHabeeb W, Akhras K, AlGhalayini K, et al. Understanding Heart Failure Burden in Middle East Countries: Economic Impact in Egypt, Saudi Arabia and United Arab Emirates. Value Health. 2018;21:S1–268. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jval.2018.04.840.

US FDA. FDA background document: Endocrinologic and Metabolic Drugs Advisory Committee meeting: October 24-25, 2018. https://www.fda.gov/media/121272/download. Accessed 18 Jun 2021.

Yancy CW, Jessup M, Bozkurt B, Writing Committee Members, et al. American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. 2013 ACCF/AHA guideline for the management of heart failure: a report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. Circulation. 2013;128(16):240–327. https://doi.org/10.1161/CIR.0b013e31829e8776.

Yancy CW, Jessup M, Bozkurt B, Butler J, Casey DE, Colvin MM, et al. 2017 ACC/AHA/HFSA Focused Update of the 2013 ACCF/AHA Guideline for the Management of Heart Failure. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2017;70(6):776–803.

National Institute of Health Care and Excellence. Chronic heart failure in adults: diagnosis and management (NICE guideline NG106). 2018. https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng106. Accessed 10 Jun 2021.

Ezekowitz JA, O’Meara E, McDonald MA, et al. Comprehensive update of the Canadian Cardiovascular Society Guidelines for the management of heart failure. Can J Cardiol. 2017;33(11):1342–433.

Management of chronic heart failure: a national clinical guideline (SIGN publication no. 147). Edinburgh: Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network (SIGN); 2016. https://www.sign.ac.uk/assets/sign147.pdf. Accessed 10 Jun 2021.

Pohar R, MacDougall D. Combination Use of Ivabradine with Sacubitril/Valsartan: A Review of Clinical Effectiveness and Guidelines. Ottawa (ON): Canadian Agency for Drugs and Technologies in Health; 2020 Feb 13. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK562925/. Accessed 12 Jun 2021

Yancy CW, Jessup M, Bozkurt B, et al. ACC/AHA/HFSA focused update of the 2013 ACCF/AHA guideline for the management of heart failure: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines and the Heart Failure Society of America. Circulation. 2017;136(6):e137–61. https://doi.org/10.1161/CIR.0000000000000509.

Solomon SD, McMurray JJV, Anand IS, PARAGON-HF Investigators and Committees, et al. Angiotensin-neprilysin inhibition in heart failure with preserved ejection fraction. N Engl J Med. 2019;381(17):1609–20. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa1908655.

Zinman B, Wanner C, Lachin JM, EMPA-REG OUTCOME Investigators, et al. Empagliflozin, cardiovascular outcomes, and mortality in type 2 diabetes. N Engl J Med. 2015;373(22):2117–28. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa1504720.

Neal B, Perkovic V, Mahaffey KW, CANVAS Program Collaborative Group, et al. Canagliflozin and cardiovascular and renal events in type 2 diabetes. N Engl J Med. 2017;377(7):644–57. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa1611925.

Perkovic V, Jardine MJ, Neal B, CREDENCE Trial Investigators, et al. Canagliflozin and renal outcomes in type 2 diabetes and nephropathy. N Engl J Med. 2019;380(24):2295–306. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa1811744.

Wiviott SD, Raz I, Bonaca MP, DECLARE–TIMI 58 Investigators, et al. Dapagliflozin and cardiovascular outcomes in type 2 diabetes. N Engl J Med. 2019;380(4):347–57. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa1812389.

Cannon CP, McGuire DK, Pratley R, VERTIS-CV Investigators, et al. Design and baseline characteristics of the eValuation of ERTugliflozin efficacy and Safety CardioVascular outcomes trial (VERTIS-CV). Am Heart J. 2018;206:11–23. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ahj.2018.08.016.

Pratley RE, Dagogo-Jack S, Cannon CP, et al. The VERTIS CV trial: cardiovascular outcomes following ertugliflozin treatment in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus and atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease. Presented at the American Diabetes Association Virtual 80th Scientific Sessions; 16 June 2020. https://www.acc.org/education-and-meetings/image-and-slide-gallery/media-detail?id=307a7e103bc04a588a3370709253fc35. Accessed 21 Jul 2021.

Zelniker TA, Wiviott SD, Raz I, et al. SGLT2 inhibitors for primary and secondary prevention of cardiovascular and renal outcomes in type 2 diabetes: a systematic review and meta-analysis of cardiovascular outcome trials. Lancet. 2019;393:31–9.

Packer M, Anker SD, Butler J, et al. Effects of sodium-glucose cotransporter 2 inhibitors for the treatment of patients with heart failure: proposal of a novel mechanism of action. JAMA Cardiol. 2017;2:1025–9.

Verma S, McMurray JJV. SGLT2 inhibitors and mechanisms of cardiovascular benefit: a state-of-the-art review. Diabetologia. 2018;61:2108–17.

Inzucchi SE, Kosiborod M, Fitchett D, et al. Improvement in cardiovascular outcomes with empagliflozin is independent of glycemic control. Circulation. 2018;138:1904–7.

Lytvyn Y, Bjornstad P, Udell JA, et al. Sodium glucose cotransporter-2 inhibition in heart failure: potential mechanisms, clinical applications, and summary of clinical trials. Circulation. 2017;136:1643–58.

Bonnet F, Scheen AJ. Effects of SGLT2 inhibitors on systemic and tissue low-grade inflammation: the potential contribution to diabetes complications and cardiovascular disease. Diabetes Metab. 2018;44:457–64.

Wanner C, Inzucchi SE, Lachin JM, et al. Empagliflozin and progression of kidney disease in type 2 diabetes. N Engl J Med. 2016;375:323–34.

Bhatt DL, Szarek M, Pitt B, et al. Sotagliflozin in patients with diabetes and chronic kidney disease. N Engl J Med. 2021;384:129–39.

McMurray JJV, Solomon SD, Inzucchi SE, et al. Dapagliflozin in patients with heart failure and reduced ejection fraction. N Engl J Med. 2019;381:1995–2008.

Packer M, Anker SD, Butler J, EMPEROR-Reduced Trial Investigators, et al. Cardiovascular and renal outcomes with empagliflozin in heart failure. N Engl J Med. 2020;383(15):1413–24. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa2022190.

Forxiga. AstraZeneca Pharmaceuticals LP; 2020. https://www.azpicentral.com/farxiga/farxiga.pdf#page=1. Accessed 21 Jun 2021.

Heerspink HJL, Stefánsson BV, Correa-Rotter R, DAPA-CKD Trial Committees and Investigators, et al. Dapagliflozin in patients with chronic kidney disease. N Engl J Med. 2020;383(15):1436–46. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa2024816.

Seferovic´ PM, Fragasso G, Petrie M, et al. Sodium glucose co-transporter-2 inhibitors in heart failure: beyond glycaemic control. The Position Paper of the Heart Failure Association of the European Society of Cardiology. Eur J Heart Fail. 2020;2:1495–503. https://doi.org/10.1002/ejhf.1954

McDonagh TA, Metra M, Adamo M, Gardner RS, Baumbach A, Böhm M, et al. 2021 ESC Guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic heart failure: Developed by the Task Force for the Diagnosis and Treatment of Acute and Chronic Heart Failure of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) with the special contribution of the Heart Failure Association (HFA) of the ESC. Eur Heart J. 2021;42(36):3599–726.

ClinicalTrials.gov. Dapagliflozin Evaluation to Improve the LIVEs of Patients With PReserved Ejection Fraction Heart Failure. (DELIVER). 2020. https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT03619213. Accessed 21 Jun 2021.

Anker SD, Butler J, Filippatos G, EMPEROR-Preserved Trial Committees and Investigators, et al. aseline characteristics of patients with heart failure with preserved ejection fraction in the EMPEROR-Preserved trial. Eur J Heart Fail. 2020;12:2383–92. https://doi.org/10.1002/ejhf.2064.

Anker SD, Filippatos BG, Ferreira JP, on behalf of the EMPEROR-Preserved Trial Investigators, et al. Empagliflozin in heart failure with a preserved ejection fraction. N Engl J Med. 2021;385(1):1451–61.

Rosano G, Quek D, Martínez F. Sodium-glucose co-transporter 2 inhibitors in heart failure: recent data and implications for practice. Card Fail Rev. 2020;6: e31. https://doi.org/10.15420/cfr.2020.23.

Zannad F, Rossignol P. Mineralocorticoid receptor antagonists and SGLT2 inhibitor therapy. JACC Heart Failure. 2021;9(4):265–7.

Shen L, Lund KS, Bengtsson O. Dapagliflozin in HFrEF patients treated with mineralocorticoid receptor antagonists: an analysis of DAPA-HF. J Am Coll Cardiol HF. 2021;9:254–64.

Packer M, Anker SD, Butler J, et al. Cardiovascular and renal outcomes with empagliflozin in heart failure. N Engl J Med. 2020;383:1413–24.

Zannad F, Ferreira JP, Pocock SJ, et al. SGLT2 inhibitors in patients with heart failure with reduced ejection fraction: a meta-analysis of the EMPEROR-Reduced and DAPA-HF trials. Lancet. 2020;396:819–29.

Morton G, Masters J, Cowburn PJ. Multidisciplinary team approach to heart failure management. Heart. 2018;104:1376–82.

Milder TY, Stocker SL, Day RO, et al. Potential safety issues with use of sodium-glucose cotransporter 2 inhibitors, particularly in people with type 2 diabetes and chronic kidney disease. Drug Saf. 2020;43:1211–21. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40264-020-01010-6.

Vaduganathan M, Greene SJ, Zhang S, Grau-Sepulveda M, DeVore AD, Butler J, et al. Applicability of US Food and Drug Administration Labeling for Dapagliflozin to Patients With Heart Failure With Reduced Ejection Fraction in US Clinical Practice: the get with the Guidelines-Heart Failure (GWTG-HF) Registry. JAMA Cardiol. 2020;6(3):1–10. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamacardio.2020.5864.

Maltês S, Cunha GJL, Rocha BML, Presume J, Guerreiro R, Henriques C, et al. Dapagliflozin in a real-world chronic heart failure population: how many are actually eligible? Cardiology. 2021;146(2):201–6. https://doi.org/10.1159/000512432.

Monzo L, Ferrari I, Cicogna F, Tota C, Calò L. Sodium-glucose co-transporter-2 inhibitors eligibility in patients with heart failure with reduced ejection fraction. Int J Cardiol. 2021;341:56–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijcard.2021.08.035.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Funding

AstraZeneca provided assistance with publication fees for open access service. No other funding was received for this paper.

Conflicts of interest/competing interests

Emad R. Issak has no conflicts of interest to declare. Ahmed S. Elserafy, Ashraf Reda, Elsayed Farag, Tamer Mostafa, Nabil Farag, Atef Elbahary, Osama Sanad, Ahmed Bendary, Ahmed Elkersh, Ihab Attiam, Mohammed Selim and Hazem Khamis have conducted scientific sessions and received honoraria from AstraZeneca, Boehringer Ingelheim, and Sanofi.

Ethics approval

Not applicable.

Consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

Code availability

Not applicable.

Author contributions

ASE: collected recommendations from the experts and wrote and revised the manuscript. ERI: literature review, medical writing, and edited and revised the manuscript. AR, EF, TM, NF, AE, OS, AB, AE, IA, MS and HK: expert opinion and revised the manuscript.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Elserafy, A.S., Reda, A., Farag, E. et al. Egyptian Atherosclerosis and Vascular Biology Association Consensus on the Use of Sodium Glucose Cotransporter-2 Inhibitors in Heart Failure with Reduced Ejection Fraction. Clin Drug Investig 41, 1027–1036 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40261-021-01095-6

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40261-021-01095-6