Abstract

Paracetamol is a common analgesic and antipyretic drug for management of fever and mild-to-moderate pain in infants and children, and it is considered as first-line therapy for the treatment of both according to international guidelines and recommendations. The mechanism of action of paracetamol is complex and multifactorial, and several aspects of the pharmacology impact its clinical use, especially in the selection of the correct analgesic and antipyretic dose. A systematic literature search was performed by following procedures for transparent reporting of systematic reviews and meta-analyses. To maximize efficacy and avoid delays in effect, use of the appropriate dose of paracetamol is paramount. Older clinical studies using paracetamol at subtherapeutic doses of ≤10 mg/kg generally show that it is less effective than non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs). However, recent evidence shows that when used at dose of 15 mg/kg for fever and pain management, paracetamol is significantly more effective than placebo, and at least as effective as NSAIDs. Paracetamol 15 mg/kg has a tolerability profile similar to that of placebo and NSAIDs such as ibuprofen and ketoprofen used for short-term treatment of fever. However, when used at repetitive doses for consecutive days, paracetamol shows lower risk of adverse events compared to NSAIDs. Also, unlike NSAIDs, paracetamol is indicated for use in children of all ages. Overall, clinical evidence qualifies paracetamol 15 mg/kg a safe and effective option for treatment of pain and fever in children.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Fever and pain occur frequently in infants and children [1]. Management of fever tends to be characterized by over-treatment, because of the parents anxiety and fever phobia [2–6], whereas management of pain is characterized by under-treatment, particularly in very young children with acute painful injuries [7, 8]. Paracetamol is a common analgesic and antipyretic drug for management of fever and mild-to-moderate pain in pediatric patients. It is the first-line choice for the treatment of both fever and pain according to national and international guidelines and recommendations and it is also included in the List of Essential Medicines for Children of the World Health Organization (WHO) [9–20].

Appropriate dosages should be used to ensure optimal efficacy and safety of paracetamol [18]. Given the wide range of body weight across children of different ages, guidelines for treatment of pain highlight the importance of administering the correct dose according to body weight, hence the use of milligram per kilogram (mg/kg) dosing [10, 12, 14, 15, 18]. Pediatric patients, especially if they have fever or pain, are acutely unwell may be frightened and less co-operative than usual [21]. Flexible formulations should guarantee the ease of administration and aid dosing accuracy. Specific oral formulations of paracetamol, as syrup and drops, should be recommended because easy to administer and because they allow selection of the right mg/kg dose. Paracetamol recommended doses vary from 10 to 15 mg/kg every 4–6 h (up to 60 mg/kg/day) [9, 14, 18, 22]. A common issue is the variability of dosages used to treat fever and pain in clinical practice, where paracetamol doses range from 5 to 20 mg/kg [9, 23–25]. Studies have shown that dose variability can depend on to the specialty of the prescribing physician, with pediatricians prescribing more suitable doses than family physicians or otolaryngologists [23].

Clinical trials have investigated different doses, with older trials focusing on doses <10 mg/kg, now known to be subtherapeutic [26–33]. More recent studies have investigated higher oral paracetamol doses 10–30 mg/kg [34–40] and the available evidence now suggests that 15 mg/kg could be the optimal dose.

The objective of this article was to review the literature and identify the analgesic and antipyretic doses of paracetamol that guarantee efficacy and safety in children. This article is based on previously conducted studies and does not involve any new studies of human or animal subjects performed by any of the authors.

Methods

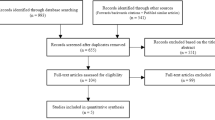

A systematic literature search was performed in Medline using the search terms [“pain” OR “fever” OR “migraine”] AND “child” AND “acetaminophen” (paracetamol) AND [“dose” or “dosing” or “dosage” or “dose-related”], both as subject headings and keywords. Papers with acetaminophen indexed as adverse effect, contraindication, metabolism, pharmacokinetics, pharmacology, therapeutic use, and toxicity were selected. No restrictions were applied to the other search terms. The search was limited to children with no date or other limits applied. The search results were de-duplicated and papers relevant to this review were selected manually. Other supporting references were sourced by specific literature searches as required, or were obtained from bibliographies of review articles or from the authors’ personal libraries.

Results of Literature Search

A total of 114 papers were found. Of these, 53 papers explicitly mentioning mg/kg dosing of paracetamol were manually selected for potential inclusion in this review. Of these, 14 were review articles, 4 were pharmacokinetic (PK)/pharmacodynamics (PD) studies, 2 were meta-analyses of clinical trials, and 23 were clinical studies of paracetamol in children either as the only arm or as one of the study arms (21 specifically studied paracetamol 15 mg/kg and 2 studied paracetamol 12 mg/kg). Papers reporting trials of 10 mg/kg or lower doses were included for comparative purposes, but are not discussed in depth.

Pharmacology

Pharmacokinetics

Paracetamol is a highly lipid-soluble compound that is readily absorbed through the gut [time to peak drug concentration (T max) 0.5–0.75 h after oral administration], with a bioavailability of nearly 90% [41–43]. It has a pKa of 9.5 and is therefore highly polarized in the stomach with very low gastric absorption [44]. Once in the basic environment of the duodenum, paracetamol rapidly crosses the mucosa and enters the bloodstream. Paracetamol shows a negligible binding to plasma proteins (10–25%), a key feature that differentiates it from other analgesics/antipyretics such as ibuprofen [24, 42]. Paracetamol is metabolized principally in the liver. In adults, glucuronide and sulfate conjugates account for 50–60% and 25–30%, respectively, and <10% remain unmodified. In children, though the metabolic pathways are the same, their relative contributions change with age, since the sulfation pathways are mature at birth while the glucuronidation pathways matures in about 2 years [24, 41]. Almost 90% of paracetamol metabolites are excreted into the urine within 24 h [24]. Paracetamol half-life (t ½) is short, ranging from 2 to 2.5 h [41].

A key issue when dealing with paracetamol pharmacology is the “effect compartment” concept that explains the time delay between therapeutic levels of paracetamol in the plasma and analgesic or antipyretic effect [24, 45]. The therapeutic effect of paracetamol is not linearly related to plasma concentration. Both antipyresis and analgesia are related to concentrations reached in the brain, with paracetamol needing to exit the bloodstream and reach the neural tissue before exerting its effects [24]. This effect compartment model has key clinical implications, both for dosing levels and dosing schedules.

The administered dosage influences the speed of onset of action and the achieved plasma concentrations, so that appropriate dosing to achieve suitable effect compartment concentrations is crucial for maximum efficacy [45].

Pharmacodynamics

The mechanism of action of paracetamol is still debated. It was first hypothesized that the drug exerts its effect via inhibition of prostaglandin synthesis by cyclooxygenase (COX); it is now known that paracetamol has several PD targets within the brain. Paracetamol inhibits COX and reduces prostaglandin synthesis, with an interaction site different from that of non-steroidal anti-inflammatories (NSAIDs) [46, 47]. NSAIDs inhibit prostaglandin synthesis by competing with arachidonic acid for the COX binding site, whereas paracetamol reduces prostanoid formation by acting at the peroxidase site [46, 47]. More precisely, paracetamol is thought to act as a reduction factor, donating electrons to the radical Fe4+ within the COX peroxidase site, thereby preventing the generation of tyrosine radials and, in turn, preventing arachidonic acid oxygenation [47]. Due to the large amounts of hydroperoxide present in inflammatory environments [48], the activity of paracetamol is diminished because cellular hydroperoxide oxidizes the radical Fe within the peroxidase site, preventing the effect that paracetamol has on arachidonic acid oxygenation [47]. Generally, hydroperoxide is present in large amounts in inflammatory environments, reducing paracetamol activity.

These findings explain why paracetamol cannot counteract inflammation and platelet aggregation, as well as its exclusive central nervous system (CNS) activity [24]. Several lines of evidence demonstrate that the ability of paracetamol to reduce fever is due to inhibition of hypothalamic prostaglandin formation [24]. Fever occurs when warm-sensitive neurons, normally responsible for triggering heat loss, are inhibited by prostaglandins, mainly prostaglandin E2 (PGE2) [20]. By inhibiting COX in neural and brain endothelial cells, paracetamol counteracts PGE2 formation, thereby relieving suppression of warm-sensitive neurons that are then free to reset thermoregulation toward lower body temperature [49]. Therefore, mechanism of antipyresis by paracetamol occurs through the canonical inhibition of COX within the CNS, akin to that exerted by classic NSAIDs.

The mechanisms of the analgesic effect of paracetamol differ from that of NSAIDs. Several lines of evidence indicate that in addition to COX inhibition, the descending, serotonergic pain control system is also associated with paracetamol analgesia [24, 47]. This occurs via indirect activation of serotonin receptors, including the 5 hydroxytryptamine3 (5HT3) subtype, on opioidergic interneurons that, in turn, reduce excitability of dorsal horn neurons projecting to the thalamus [21]. Accordingly, the 5HT3 receptor antagonists tropisetron or granisetron completely prevent analgesia prompted by 1 g oral paracetamol [50, 51]. An additional mechanism through which paracetamol prompts analgesia might be its transformation into N-arachidonyl-aminophenol (also called AM404) by fatty acid hydrolase, an enzyme highly expressed within the brain. AM404 activates TRPV1 on terminal of nociceptors, but also inhibits COX1-2, and favors cannabinoid receptor-1 (CB1)-dependent analgesia by counteracting cellular uptake of the endogenous CB1 receptor agonist anandamide [24, 47].

Antipyresis by Paracetamol: Pharmacology-Based Practical Implications

Due to indisputable ethical reasons, repetitive cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) sampling cannot be obtained in children for research. As a consequence, maximal antipyretic effects (E max) or the plasma/CSF concentration producing half of E max (EC50) are merely estimated from empirical data deriving from specific assessments. PK studies of paracetamol report an E max of 3 °C and a plasma EC50 of 9.7 mg/L obtained with classic doses of 10–15 mg/kg [52, 53]. Although evidence suggests that paracetamol 10–12.5 mg/kg is effective at antipyresis in children, as mentioned above there is a delay between the achievement of appropriate paracetamol concentrations and onset of action [24]. This time delay is a key aspect of practical treatment of fever in children, so augmenting the dose or selecting the highest dose is most likely to provide the onset and duration of action necessary for clinical improvement. Gibb and Anderson [45] suggested that increasing the paracetamol dose would speed up onset of antipyresis. A recent analysis of data from 3155 feverish children receiving paracetamol in 53 studies partly confirms Gibb and Anderson estimation [25].

Temple et al. [25] also showed that 15 mg/kg produced a larger relative temperature reduction and a longer duration of substantial temperature reduction compared with 10 mg/kg. After 30 min, 15 mg/kg paracetamol decreased body temperature by 0.71 °C, while 10 mg/kg paracetamol reduced body temperature by 0.36 °C (i.e., only 0.4 °C higher than that achieved with the lower dose). However, duration of antipyresis was substantially longer with the dose of 15 mg/kg. 15 mg/kg oral paracetamol was associated with a mean temperature reduction of about 1 °C greater than that observed with the 10 mg/kg dose after 8 h (−1.35 vs. −0.65 °C change in temperature with 15 and 10 mg/kg at 8 h, respectively) [25]. A review summarizing available PK/PD (fever reduction) data of oral paracetamol in children aged 6 months to 12 years concluded that the antipyretic effect of paracetamol is dose dependent [22]. In the dose range of 10–15 mg/kg, paracetamol was more effective than placebo in this analysis. Variables such as the initial temperature and the age of the patient can influence the antipyretic response of paracetamol [42]. Taken together, data indicate that 15 mg/kg, allowing an earlier onset and a longer duration of effect is an optimal, oral paracetamol dose for an antipyretic effect.

Analgesia by Paracetamol: Pharmacology-Based Practical Implications

The molecular mechanisms responsible for fever reduction and analgesia by paracetamol differ substantially. The pleiotypic mechanisms of paracetamol-induced analgesia have important consequences in determining the correct use of this drug for the efficient treatment of pain. A key aspect of paracetamol analgesia is that it occurs at CNS drug concentrations higher than those required for antipyresis [24]. Specifically, it has been reported that plasma EC50 of antipyresis (4.63 mg/L) is almost half of that of analgesia (9.98 mg/L) [45].

Although the pharmacological basis of the higher plasma EC50 required to treat pain still needs to be unequivocally determined, it is conceivable that it is mainly related to the various mechanisms of paracetamol analgesia. Indeed, it is plausible that the drug must reach CNS concentrations higher than those able to inhibit COX to fully activate the pain-suppressing effect on opioid receptor and descending serotonergic pathway. These different PD features translate into different therapeutic approaches in the clinical setting, altering the practical use of the drug when treating fever or pain in children to obtain maximal therapeutic benefit.

The time delay caused by the effect compartment must also be taken into account when choosing an appropriate dose of paracetamol, since there is a threshold concentration required in the CNS before analgesic activity is produced, and under-dosing results in a delay in pain reduction. The minimum target effect compartment concentration is 11.8 mg/L for pain relief in children. At least 15 mg/kg is required orally to achieve analgesic paracetamol levels [54]. The possible time delay should also drive the choice of time interval between repeated doses, so that appropriate steady-state plasma levels are reached in a timely manner.

Unfortunately, the time–concentration relationship has not been determined after multiple paracetamol dosing. However, it is possible to extrapolate such a relationship by analyzing data from the literature. Specifically, evidence that a dose of 15 mg/kg in adults leads to a peak drug concentration (C max) of 11.8 mg/L [55, 56], together with the notion that in the plasma concentrations increase linearly with dose, allows an estimation of a C max of 12.6 mg/L following a dose of 15 mg/kg. This information along with that provided by the study by Hopkins et al. [57] which showed plasma T max and t ½, respectively, of 114 and 138 min in children receiving 15 mg/kg of oral paracetamol means an approximate time/concentration relationship describing plasma values in children can be constructed (Fig. 1). To determine this relationship following multiple oral doses of 15 mg/kg, the data from the study by Nahata et al. [58], which reported a 13.35% plasma accumulation at the steady state in children receiving this dose in a repetitive dosing paradigm, can be employed. Combining these PK parameters produces a time/plasma concentration curve after repetitive (every 6 h) 15 mg/kg oral dosing (Fig. 2). This estimation indicates that steady state of plasma concentrations of 14.28 mg/L is reached within 20 h after initiating repetitive dosing. Remarkably, steady-state concentrations of 14.28 mg/L are above the pain threshold of 11 mg/L identified by the study by Brett and colleagues [54]. These extrapolations suggest that oral dosing of paracetamol at 15 mg/kg every 6 h permits rapid achievement of steady-state concentrations and C max well above those required to prompt analgesia. Still, to expedite onset of pain resolution, adoption of a loading dose will obviously shift the time–concentration curve depicted in Fig. 1 upward, thereby allowing faster attainment of steady state. Remarkably, these data, based both on empirical findings and estimations, nicely fit with guidelines proposed by different institutions: that regimens of 15 mg/kg oral paracetamol every 6 h provide efficient pain control in children [14].

Clinical Management of Fever with Paracetamol

The pharmacological treatment of fever in children and infants should be carried to reduce the discomfort of the child, not to fight fever per se. Frequently, fever in children causes anxiety in the parents that if not properly managed can lead to mistakes, even in the choice of medication and the appropriate dose.

In general, paracetamol is the only antipyretic approved for use in children from birth and it is indicated as the drug of choice in pediatric guidelines for the management of fever in children [13, 15]. Unlike ibuprofen, which is approved for use in children over 3 years of age, paracetamol is indicated in patients with chickenpox and in those with dehydration and pneumonia [13, 14].

Clinical Trial Data

Clinical data for 15 mg/kg paracetamol in children with fever are summarized in Table 1. These studies investigated paracetamol 12–15 mg/kg vs. ibuprofen [34, 35, 40, 59, 60], ketoprofen [59], dipyrone [40], and placebo [38, 61]. Compared with ibuprofen and ketoprofen, paracetamol 15 mg/kg had a comparable efficacy [34, 35, 40, 59, 60]. Dipyrone was more effective than paracetamol at temperature normalization and temperature reduction [40]. Compared with placebo, paracetamol showed a better efficacy profile [38, 61]. Ibuprofen, ketoprofen and dipyrone used for short term had similar safety profile to paracetamol [34, 35, 40, 59, 60] that in turn shows a similar or better tolerability profile to placebo (Table 1) [38, 61].

Other studies have shown similar results. A recent systematic review of clinical data showed that the 10–15 mg/kg oral dose first recommended in 1983 is still appropriate for the treatment of fever in children [25]. However, as mentioned above, the same review also showed data in which 15 mg/kg paracetamol was better at reducing temperature for longer time than 10 mg/kg paracetamol, the mean maximum temperature decrease from baseline was 1.17 °C in the 10 mg/kg studies and 1.60 °C in the 15 mg/kg studies, and the temperature decrease from baseline at 480 min was 0.65 °C in the 10 mg/kg studies and 1.35 °C in the 15 mg/kg studies [25]. These results are supported by additional clinical trials of 10 mg/kg, paracetamol which generally was consistently less effective than ibuprofen [27–29, 62]. The importance of choosing the right dose of paracetamol to treat fever should be strongly stressed, since a low dose could compromise effectiveness, and physicians should carefully choose the dose of paracetamol guaranteeing antipyretic efficacy and safety in children. The clinical trial data presented suggest that paracetamol 15 mg/kg is the most appropriate choice for rapid and effective fever reduction.

Clinical Management of Pain with Paracetamol

In children with pain and headache, the recommended dose of paracetamol is 10–15 mg/kg administered 3–4 times a day to a maximum dose of 60 mg/kg/day [18, 19]. The most appropriate medication for the treatment of pain should be chosen based on the underlying cause of the pain. Options include NSAIDs and paracetamol. Paracetamol is not recommended for anti-inflammatory use [63]; however, it is the most appropriate drug in children with pain of a non-inflammatory etiology [15, 18]. A systematic review investigated paracetamol as an opioid-sparing treatment in children with perioperative pain [64]. While the results were mixed, with paracetamol allowing for opioid sparing in some studies but not others, the authors acknowledged that the variability in effectiveness may have been due to inadequate paracetamol dosing and variable absorption seen with rectal paracetamol, and stressed the importance of appropriate paracetamol dosing and route of administration [64].

Clinical Trial Data

Clinical data for paracetamol 15 mg/kg in children with pain are summarized in Table 2. Paracetamol has been compared with ibuprofen [39, 65–68], ketoprofen [69], naproxen [70], and codeine [66] in this setting. Studies of the use of paracetamol in pain show that paracetamol is generally as effective as ibuprofen, naproxen, and ketoprofen in reducing pain [39, 65, 69, 70]. In two studies, there was a significant difference between paracetamol and ibuprofen, with one study favoring ibuprofen [66], and one favoring paracetamol [68] (Table 2). Also, when used a single agents, paracetamol was as effective as codeine at reducing pain caused by musculoskeletal injury [66]. Generally, paracetamol was more effective than placebo at reducing pain [39, 68, 69]. In the treatment of migraine, both paracetamol and ibuprofen were more effective than placebo at reducing headache pain [67]. As for the clinical trials in fever, the tolerability of paracetamol was similar to that of ibuprofen, naproxen, ketoprofen, used for short-term treatment, and placebo (Table 2).

A systematic review of 17 clinical trials showed that single-dose paracetamol 7–15 mg/kg had similar analgesic effect to ibuprofen 4–10 mg/kg in moderate to severe pain [71]. Similarly, a systematic review of 10 clinical trials in the use of paracetamol 15 mg/kg to treat migraine showed that paracetamol is as effective as ibuprofen and nimesulide at reducing migraine symptoms, and more effective than placebo with a similar tolerability profile [72].

Tolerability and Safety

The WHO has highlighted the need for long-term safety data for paracetamol and ibuprofen [18]. The adverse event profile of paracetamol vs. active comparators and placebo in the treatment of fever and pain and migraine is outlined in detail in Tables 1 and 2. Generally, the adverse events associated with paracetamol were of similar or lesser frequency than active comparators; in some cases, paracetamol recipients had similar levels of AEs to NSAIDs [34, 70] but in most cases the incidence of general AEs was lower [40, 65, 66]. NSAIDs typically had a higher incidence of gastrointestinal AEs than paracetamol, and the same also occurs even when they are used for short term [34, 40, 59, 65].

Generally, paracetamol is a very safe drug that is used extensively for the treatment of fever and pain worldwide. Government body guidelines state that paracetamol is safe for use throughout pregnancy; indeed, Italian authorities have designated it as the drug of choice for pain relief when administered at therapeutic doses (<3 g/day) to pregnant women. Data suggests that paracetamol use during pregnancy does not result in congenital anomalies, and it is not contraindicated during breastfeeding. Furthermore, paracetamol can be effective in the management of ductus arteriosus in neonates, achieving high rates of ductal closure in the absence of adverse events [73]. While there may be an increased risk of asthma and behavioral issues such as attention-deficit disorder with paracetamol use in pregnancy, these results have yet to be confirmed and are likely subject to confounding factors [74]. The association may be a consequence of reverse causality bias [75] or the influence of respiratory tract infections during pregnancy [76, 77].

Paracetamol toxicity can result in cases of overdose or where there are underlying conditions present [78]. As with any drug, care must be used when administering paracetamol to children who may be suffering from dehydration [79], malnutrition, or receiving concomitant medications [18]. Chronic overdosing of paracetamol is linked to hepatic injury prompted by the paracetamol metabolite N-acetyl benzoquinone (NAPQI) and necessitates prompt N-acetylcysteine treatment [9], however, severe liver injury with short courses of supratherapeutic doses is rare [80]. Toxicity in children tends to occur after administration of single doses ranging from 120 to 150 mg/kg (Fig. 3), which is 10–15 times the recommended dosage [78], even though idiosyncratic reactions associated to increased activity of the hepatic cytochrome P450 detoxifying system have been reported [85]. Sustained dosing (>1 day) with >90 mg/kg/day (whereas the recommended dosing 60 mg/kg/day) puts children aged <2 years at high risk for hepatotoxicity [81]. Case reports describe children presenting with paracetamol toxicity after sustained dosing of 100–367 mg/kg/day [81]. A recent study conducted in Australia and New Zealand revealed that hepatic failure due to paracetamol ingestion occurred in children mostly as a result of medication errors such as doses in excess of 120 mg/kg/day, double dose, too frequent administration, coadministration of other medicines containing paracetamol or regular paracetamol for up to 24 days [82]. Also, as far as the potential risk of asthma and allergy in children treated with paracetamol is concerned, a clear causative role still needs to be unequivocally demonstrated because the initial paracetamol use–asthma incidence association [86] has been recently diminished by considering respiratory tract infection as a confounding factor [87]. Finally, results from recent clinical trials indicate that prophylactic use of paracetamol to prevent febrile reactions after immunization is not indicated because of the risk of reduced immunoglobulin production [88].

Conclusions

Due to the pharmacology of paracetamol, it is important to choose an appropriate dose to get maximum efficacy while minimizing adverse effects. In children, paracetamol 15 mg/kg is the appropriate dose to use for treatment of fever. In the treatment of pain in children, the minimum dose of paracetamol that should be used is 15 mg/kg. According to WHO guidelines, the only available option for pain management in children below 3 months of age is paracetamol; the 10 mg/kg dose every 4–6 h should be recommended in this case [18]. For the effective control of pain, paracetamol should be given as a scheduled dose over time, and not administered at need. The correct dose of paracetamol provides effective treatment of pain and fever that is equivalent to that seen with NSAIDs, making it an effective and safer treatment option in this setting.

Only paracetamol and ibuprofen appear recommended for reduction of fever in children [15]. It is not recommended to use them in combination or alternating paracetamol and ibuprofen. Also, whereas ibuprofen is not approved for use in children under three months of age and is contraindicated in patients with chickenpox and in those with dehydration and pneumonia, paracetamol can be used from birth and in patients with dehydration [13, 14]. As for analgesia in children suffering from mild-to-moderate pain, paracetamol appears the drug of choice with an optimal dosage of 15 mg/kg every 4–6 h (no more than 4 times per day) [83]. Of note, paracetamol is also the drug of choice for the treatment of mild-to-moderate pain in neonates [83]. Finally, to avoid toxicity only standard doses should be used, with doses calculated according to weight and age; attention must also be paid to any clinical factors or concomitant medications that may increase the risk of toxicity.

References

van den Anker JN. Optimising the management of fever and pain in children. Int J Clin Pract Suppl. 2013;26–32.

Chiappini E, Parretti A, Becherucci P, Pierattelli M, Bonsignori F, Galli L, et al. Parental and medical knowledge and management of fever in Italian pre-school children. BMC Pediatr. 2012;12:97.

Purssell E. Fever phobia revisited. Arch Dis Child. 2004;89:89–90.

Kanabar D. A practical approach to the treatment of low-risk childhood fever. Drugs R D. 2014;14:45–55.

Betz MG, Grunfeld AF. ‘Fever phobia’ in the emergency department: a survey of children’s caregivers. Eur J Emerg Med. 2006;13:129–33.

Poirier MP, Collins EP, McGuire E. Fever phobia: a survey of caregivers of children seen in a pediatric emergency department. Clin Pediatr. 2010;49:530–4.

Alexander J, Manno M. Underuse of analgesia in very young pediatric patients with isolated painful injuries. Ann Emerg Med. 2003;41:617–22.

Seupaul RA. Oligoanalgesia in very young pediatric patients. Ann Emerg Med. 2004;43:292 (auth reply 3).

Cranswick N, Coghlan D. Paracetamol efficacy and safety in children: the first 40 years. Am J Ther. 2000;7:135–41.

Green R, Jeena P, Kotze S, Lewis H, Webb D, Wells M. Management of acute fever in children: guideline for community healthcare providers and pharmacists. S Afr Med J. 2013;103:948–54.

Guideline statement: management of procedure-related pain in children and adolescents. J Paediatr Child Health. 2006;42(Suppl 1):S1–29.

Stapelkamp C, Carter B, Gordon J, Watts C. Assessment of acute pain in children: development of evidence-based guidelines. Int J Evid Based Healthc. 2011;9:39–50.

The National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE). NICE clinical guideline 160. Feverish illness in children: assessment and initial management in children younger than 5 years. 2013. Available from URL: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg160. Accessed 21 Jan 2015.

Italian Ministry of Health. Pain in children: practical instruments for assessment and therapy. 2013. Available from URL: http://www.salute.gov.it/imgs/C_17_pubblicazioni_1256_allegato.pdf. Accessed 21 Jan 2015.

Italian Society of Pediatrics (Società Italiana di Pediatria). Gestione del segno/sintomo febbre in pediatria: Linee Guida della Società Italiana di Pediatria. 2013 [Management of the fever sign/symptoms in children: Guidelines of the Italian Society of Pediatrics, 2013]. Available from URL: http://www.snlg-iss.it/cms/files/LG_SIP_febbre.pdf. Accessed 21 Jan 2015].

Savoia G, Coluzzi F, Di Maria C, Ambrosio F, Della Corte F, Oggioni R, et al. Italian Intersociety Recommendations (SIAARTI, SIMEU, SIS 118, AISD, SIARED, SICUT, IRC) on Pain Management in the Emergency Setting. Minerva Anestesiol. 2014.

de Martino M, Mansi N, Principi N, Serra A. Italian Guidelines: Management of Pharynotonsillitis in Children. 2011. Available from URL: http://www.snlg-iss.it/cms/files/LG_faringotonsillite.pdf. Accessed 21 Jan 2015.

World Health Organization. WHO guidelines on the pharmacological treatment of persisting pain in children with medical illnesses. 2012. Available from URL: http://whqlibdoc.who.int/publications/2012/9789241548120_Guidelines.pdf. Accessed 21 Jan 2015.

Italian Society for the Study of Headaches. Guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of pediatric headaches. 2003. Available from URL: http://www.sinpia.eu/atom/allegato/153.pdf. Accessed 21 Jan 2015.

Fields E, Chard J, Murphy MS, Richardson M. Assessment and initial management of feverish illness in children younger than 5 years: summary of updated NICE guidance. BMJ. 2013;346:f2866.

European Medicines Agency (EMEA) Committee for Medicinal Products for Human Use (CHMP). Reflection paper: formulations of choice for the paediatric population. 28 July 2006. Available at URL: http://www.ema.europa.eu/docs/en_GB/document_library/Scientific_guideline/2009/09/WC500003782.pdf. Accessed 21 Jan 2015.

Ji P, Wang Y, Li Z, Doddapaneni S, Hertz S, Furness S, et al. Regulatory review of acetaminophen clinical pharmacology in young pediatric patients. J Pharm Sci. 2012;101:4383–9.

Chou YC, Lin SY, Chen TJ, Chiang SC, Jeng MJ, Chou LF. Dosing variability in prescriptions of acetaminophen to children: comparisons between pediatricians, family physicians and otolaryngologists. BMC Pediatr. 2013;13:64.

Marzuillo P, Guarino S, Barbi E. Paracetamol: a focus for the general pediatrician. Eur J Pediatr. 2014;173:415–25.

Temple AR, Temple BR, Kuffner EK. Dosing and antipyretic efficacy of oral acetaminophen in children. Clin Ther. 2013;35(1361–75):e1–45.

McIntyre J, Hull D. Comparing efficacy and tolerability of ibuprofen and paracetamol in fever. Arch Dis Child. 1996;74:164–7.

Van Esch A, Van Steensel-Moll HA, Steyerberg EW, Offringa M, Habbema JD, Derksen-Lubsen G. Antipyretic efficacy of ibuprofen and acetaminophen in children with febrile seizures. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 1995;149:632–7.

Autret E, Breart G, Jonville AP, Courcier S, Lassale C, Goehrs JM. Comparative efficacy and tolerance of ibuprofen syrup and acetaminophen syrup in children with pyrexia associated with infectious diseases and treated with antibiotics. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 1994;46:197–201.

Kauffman RE, Sawyer LA, Scheinbaum ML. Antipyretic efficacy of ibuprofen vs acetaminophen. Am J Dis Child. 1992;146:622–5.

Joshi YM, Sovani VB, Joshi VV, Navrange JR, Benakappa DG, Shivananda P, et al. Comparative evaluation of the antipyretic efficacy of ibuprofen and paracetamol. Indian Pediatr. 1990;27:803–6.

Walson PD, Galletta G, Braden NJ, Alexander L. Ibuprofen, acetaminophen, and placebo treatment of febrile children. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 1989;46:9–17.

Polidori G, Titti G, Pieragostini P, Comito A, Scaricabarozzi I. A comparison of nimesulide and paracetamol in the treatment of fever due to inflammatory diseases of the upper respiratory tract in children. Drugs. 1993;46(Suppl 1):231–3.

Kapoor SK, Sharma J, Batra B, Paul E, Anand K, Sharma D. Comparison of antipyretic effect of nimesulide and paracetamol in children attending a secondary level hospital. Indian Pediatr. 2002;39:473–7.

Autret-Leca E, Gibb IA, Goulder MA. Ibuprofen versus paracetamol in pediatric fever: objective and subjective findings from a randomized, blinded study. Curr Med Res Opin. 2007;23:2205–11.

Carabano Aguado I, Jimenez Lopez I, Lopez-Ceron Pinilla M, Calvo Garcia I, Pello Lazaro AM, Balugo Bengoechea P, et al. Antipyretic effectiveness of ibuprofen and paracetamol. An Pediatr 2005;62:117–22.

Treluyer JM, Tonnelier S, d’Athis P, Leclerc B, Jolivet-Landreau I, Pons G. Antipyretic efficacy of an initial 30-mg/kg loading dose of acetaminophen versus a 15-mg/kg maintenance dose. Pediatrics. 2001;108:E73.

And which works better on fever–acetaminophen, ibuprofen, or both? Child Health Alert. 2008;26:1–2.

Gupta H, Shah D, Gupta P, Sharma KK. Role of paracetamol in treatment of childhood Fever: a double-blind randomized placebo controlled trial. Indian Pediatr. 2007;44:903–11.

Salmassian R, Oesterle LJ, Shellhart WC, Newman SM. Comparison of the efficacy of ibuprofen and acetaminophen in controlling pain after orthodontic tooth movement. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 2009;135:516–21.

Wong A, Sibbald A, Ferrero F, Plager M, Santolaya ME, Escobar AM, et al. Antipyretic effects of dipyrone versus ibuprofen versus acetaminophen in children: results of a multinational, randomized, modified double-blind study. Clin Pediatr. 2001;40:313–24.

Bannwarth B, Pehourcq F. Pharmacologic basis for using paracetamol: pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic issues. Drugs. 2003;63 Spec No 2:5–13.

Litalien C, Jacqz-Aigrain E. Risks and benefits of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs in children: a comparison with paracetamol. Paediatr Drugs. 2001;3:817–58.

Rawlins MD, Henderson DB, Hijab AR. Pharmacokinetics of paracetamol (acetaminophen) after intravenous and oral administration. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 1977;11:283–6.

Bagnall WE, Kelleher J, Walker BE, Losowsky MS. The gastrointestinal absorption of paracetamol in the rat. J Pharm Pharmacol. 1979;31:157–60.

Gibb IA, Anderson BJ. Paracetamol (acetaminophen) pharmacodynamics: interpreting the plasma concentration. Arch Dis Child. 2008;93:241–7.

Graham GG, Scott KF. Mechanism of action of paracetamol. Am J Ther. 2005;12:46–55.

Jozwiak-Bebenista M, Nowak JZ. Paracetamol: mechanism of action, applications and safety concern. Acta Pol Pharm. 2014;71:11–23.

Wittmann C, Chockley P, Singh SK, Pase L, Lieschke GJ, Grabher C. Hydrogen peroxide in inflammation: messenger, guide, and assassin. Adv Hematol. 2012;2012:541471.

Morrison SF, Nakamura K. Central neural pathways for thermoregulation. Front Biosci. 2011;16:74–104.

Pickering G, Esteve V, Loriot MA, Eschalier A, Dubray C. Acetaminophen reinforces descending inhibitory pain pathways. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2008;84:47–51.

Pickering G, Loriot MA, Libert F, Eschalier A, Beaune P, Dubray C. Analgesic effect of acetaminophen in humans: first evidence of a central serotonergic mechanism. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2006;79:371–8.

Anderson BJ, Holford NH, Woollard GA, Chan PL. Paracetamol plasma and cerebrospinal fluid pharmacokinetics in children. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 1998;46:237–43.

Kelley MT, Walson PD, Edge JH, Cox S, Mortensen ME. Pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of ibuprofen isomers and acetaminophen in febrile children. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 1992;52:181–9.

Brett CN, Barnett SG, Pearson J. Postoperative plasma paracetamol levels following oral or intravenous paracetamol administration: a double-blind randomised controlled trial. Anaesth Intensive Care. 2012;40:166–71.

Anderson B, Kanagasundarum S, Woollard G. Analgesic efficacy of paracetamol in children using tonsillectomy as a pain model. Anaesth Intensive Care. 1996;24:669–73.

Rumack BH. Aspirin versus acetaminophen: a comparative view. Pediatrics. 1978;62:943–6.

Hopkins CS, Underhill S, Booker PD. Pharmacokinetics of paracetamol after cardiac surgery. Arch Dis Child. 1990;65:971–6.

Nahata MC, Powell DA, Durrell DE, Miller MA. Acetaminophen accumulation in pediatric patients after repeated therapeutic doses. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 1984;27:57–9.

Celebi S, Hacimustafaoglu M, Aygun D, Arisoy ES, Karali Y, Akgoz S, et al. Antipyretic effect of ketoprofen. Indian J Pediatr. 2009;76:287–91.

Hay AD, Costelloe C, Redmond NM, Montgomery AA, Fletcher M, Hollinghurst S, et al. Paracetamol plus ibuprofen for the treatment of fever in children (PITCH): randomised controlled trial. BMJ. 2008;337:a1302.

Kramer MS, Naimark LE, Roberts-Brauer R, McDougall A, Leduc DG. Risks and benefits of paracetamol antipyresis in young children with fever of presumed viral origin. Lancet. 1991;337:591–4.

Autret E, Reboul-Marty J, Henry-Launois B, Laborde C, Courcier S, Goehrs JM, et al. Evaluation of ibuprofen versus aspirin and paracetamol on efficacy and comfort in children with fever. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 1997;51:367–71.

World Health Organization. WHO Model List of Essential Medicines for Children; 4th list. 8 July 2013. Available from URL: http://www.who.int/medicines/publications/essentialmedicines/4th_EMLc_FINAL_web_8Jul13.pdf. Accessed 21 Jan 2015.

Wong I. St John-Green C, Walker SM. Opioid-sparing effects of perioperative paracetamol and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) in children. Paediatr Anaesth. 2013;23:475–95.

Shepherd M, Aickin R. Paracetamol versus ibuprofen: a randomized controlled trial of outpatient analgesia efficacy for paediatric acute limb fractures. Emerg Med Australas. 2009;21:484–90.

Clark E, Plint AC, Correll R, Gaboury I, Passi B. A randomized, controlled trial of acetaminophen, ibuprofen, and codeine for acute pain relief in children with musculoskeletal trauma.[Erratum appears in Pediatrics. 2007 Jun; 119(6):1271]. Pediatrics. 2007;2007(119):460–7.

Hamalainen ML, Hoppu K, Valkeila E, Santavuori P. Ibuprofen or acetaminophen for the acute treatment of migraine in children: a double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled, crossover study. Neurology. 1997;48:103–7.

Mahgoobifard M, Mirmesdagh Y, Imani F, Najafi A, Nataj-Majd M. The analgesic efficacy of preoperative oral Ibuprofen and acetaminophen in children undergoing adenotonsillectomy: a randomized clinical trial. Anesth Pain Med. 2014;4:e15049.

Ruperto N, Carozzino L, Jamone R, Freschi F, Picollo G, Zera M, et al. A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of paracetamol and ketoprofren lysine salt for pain control in children with pharyngotonsillitis cared by family pediatricians. Ital J Pediatr. 2011;37:48.

Cukiernik VA, Lim R, Warren D, Seabrook JA, Matsui D, Rieder MJ. Naproxen versus acetaminophen for therapy of soft tissue injuries to the ankle in children. Ann Pharmacother. 2007;41:1368–74.

Perrott DA, Piira T, Goodenough B, Champion GD. Efficacy and safety of acetaminophen vs ibuprofen for treating children’s pain or fever: a meta-analysis. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2004;158:521–6.

Damen L, Bruijn JK, Verhagen AP, Berger MY, Passchier J, Koes BW. Symptomatic treatment of migraine in children: a systematic review of medication trials. Pediatrics. 2005;116:e295–302.

Memisoglu A, Alp Unkar Z, Cetiner N, Akalin F, Ozdemir H, Bilgen HS, et al. Ductal closure with intravenous paracetamol: a new approach to patent ductus arteriosus treatment. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2015:1–4.

Agenzia Italiana del Farmaco. Paracetamol and pregnancy.

Chang KC, Leung CC, Tam CM, Kong FY. Acetaminophen and asthma: spurious association? Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2011;183:1570 (author reply-1).

Cheelo M, Lodge CJ, Dharmage SC, Simpson JA, Matheson M, Heinrich J, et al. Paracetamol exposure in pregnancy and early childhood and development of childhood asthma: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Arch Dis Child. 2015;100:81–9.

Schnabel E, Heinrich J, Group LS. Respiratory tract infections and not paracetamol medication during infancy are associated with asthma development in childhood. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2010;126:1071–3.

American Academy of Pediatrics. Acetaminophen toxicity in children. Pediatrics. 2001;108:1020–4.

Onay OS, Ercoban HS, Bayrakci US, Melek E, Cengiz N, Baskin E. Acute, reversible nonoliguric renal failure in two children associated with analgesic-antipyretic drugs. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2009;25:263–6.

Kozer E, Barr J, Bulkowstein M, Avgil M, Greenberg R, Matias A, et al. A prospective study of multiple supratherapeutic acetaminophen doses in febrile children. Vet Hum Toxicol. 2002;44:106–9.

Shivbalan S, Sathiyasekeran M, Thomas K. Therapeutic misadventure with paracetamol in children. Indian journal of pharmacology. 2010;42:412–5.

Rajanayagam J, Bishop JR, Lewindon PJ, Evans HM. Paracetamol-associated acute liver failure in Australian and New Zealand children: high rate of medication errors. Arch Dis Child. 2015;100:77–80.

Ministero della Salute. I dolore nel bambino: strumenti pratici di valutazione e terapia, 2013.

Reymond D, Birrer P, Luthy AR, Rimensberger PC, Beck MN. Antipyretic effect of parenteral paracetamol (propacetamol) in pediatric oncologic patients: a randomized trial. Pediatr Hematol Oncol. 1997;14:51–7.

Grieco A, Miele L, Forgione A, Ragazzoni E, Vecchio FM, Gasbarrini G. Mild hepatitis at recommended doses of acetaminophen in patients with evidence of constitutionally enhanced cytochrome P450 system activity. J Clin Pharm Ther. 2008;33:315–20.

McBride JT. The association of acetaminophen and asthma prevalence and severity. Pediatrics. 2011;128:1181–5.

Sordillo JE, Scirica CV, Rifas-Shiman SL, Gillman MW, Bunyavanich S, Camargo CA Jr, Weiss ST, Gold DR, Litonjua AA. Prenatal and infant exposure to acetaminophen and ibuprofen and the risk for wheeze and asthma in children. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2015;135:441–8.

Prymula R, Siegrist CA, Chlibek R, Zemlickova H, Vackova M, Smetana J, Lommel P, Kaliskova E, Borys D, Schuerman L. Effect of prophylactic paracetamol administration at time of vaccination on febrile reactions and antibody responses in children: two open-label, randomised controlled trials. Lancet. 2009;374:1339–50.

Acknowledgments

No funding or sponsorship was received for publication of this article. All named authors meet the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors (ICMJE) criteria for authorship for this manuscript, take responsibility for the integrity of the work as a whole, and have given final approval for the version to be published.

Disclosures

Maurizio de Martino declares research grants/speaking honoraria form SKF; Novartis; Angelini; and Pfizer. Alberto Chiarugi declares research grants/speaking honoraria from Angelini; Astra Zeneca; Italfarmaco; and Thea.

Compliance with ethics guidelines

This article is based on previously conducted studies and does not involve any new studies of human or animal subjects performed by any of the authors.

Open Access

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/), which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0), which permits use, duplication, adaptation, distribution, and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

de Martino, M., Chiarugi, A. Recent Advances in Pediatric Use of Oral Paracetamol in Fever and Pain Management. Pain Ther 4, 149–168 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40122-015-0040-z

Received:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40122-015-0040-z