Abstract

Introduction

Androgenetic alopecia (AGA) is the most common cause of hair loss among males, characterized by progressive thinning of the scalp hairs and defined by various patterns. The main factors underling hair loss in AGA are genetic predisposition and increased sensitivity of the hair follicles to androgens, leading to a shortening of the anagen phase. In the present study, the authors investigated the efficacy of a commercially available cosmetic lotion, Crescina® HFSC (human follicle stem cell; Labo Cosprophar AG, Basel, Switzerland), in promoting hair growth and in decreasing hair loss.

Methods

A placebo-controlled, randomized trial was carried out on healthy males suffering from alopecia grade II to IV. Anagen rate and hair resistance to traction (pull test) were assessed after 2 and 4 months of treatment using phototricogram and pull test technique.

Results

Crescina® HFSC applied for 4 months was effective in promoting hair growth and in decreasing hair loss. After 2 and 4 months of treatment, the anagen rate was increased by 6.8% and 10.7%, respectively. Hair resistance to traction was decreased by 29.6% and 46.8%, respectively.

Conclusions

The present study demonstrated the positive effect of Crescina® HFSC in modulating the activity of the hair follicle and promoting hair growth.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Androgenetic alopecia (AGA) is the most common cause of hair loss among males [1]. It is characterized by progressive thinning of the scalp hairs, defined by various patterns [2], which can start at any age after puberty and is potentially reversible. Even if from a medical point of view, AGA is considered a relatively mild condition; however, people suffering from this condition consider AGA a serious condition that impacts their self-esteem, well-being, social relationships, and confidence.

The main factors underling hair loss in AGA are genetic predisposition and increased sensitivity of the hair follicles to androgens [3]. AGA is often precipitated and exacerbated by conditions that can induce telogen effluvium, including drugs, acute stressors, and weight loss [4]. However, in recent years it has been shown that other factors, such as microinflammation [5], decreased microcirculation [6], and aging [7], can cause hair loss in AGA. These changes contribute to shifting the normal balance of the hair cycle leading to a shortening of the anagen phase. The major components of balding in AGA are frontotemporal recession and loss of hair over the vertex. Hairs become shorter and finer, and finally complete hair loss occurs except at the lateral and posterior margins of scalp, where hair is retained.

Histologically, in AGA large terminal follicles diminish in size during hair cycles, and the resulting miniaturized follicle eventually produces a microscopic hair. Testosterone is necessary for miniaturization, and 5-alpha-reductase inhibitors, which block the conversion of testosterone to its more active form dihydrotestosterone (DHT), delay the progression of AGA [8]. Recently, Garza and coworkers [9] reported the preservation of stem cell population and a decreased conversion of hair follicle stem cells to progenitor cells in bald scalp biopsies from AGA individuals. This finding is consistent with the current clinical concept that AGA is a nonscarring type of alopecia and suggests potential reversibility of the condition.

Currently, only two medications, based on finasteride and minoxidil as active pharmacological ingredients, are approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for AGA treatment. However, they are costly, require lifelong treatment, and may have side effects. Furthermore, people are frequently reluctant/intimidated by the pharmacological approach to treat a disease that is not life threatening. Thus, a topical, nonpharmacological, effective cosmetic treatment could be more acceptable to patients.

The aim of the present study was to assess the efficacy of the use of a patented (US 6,479,059 B2 and CH 703 390), topical cosmetic product, Crescina® HFSC (human follicle stem cell; Labo Cosprophar AG, Basel, Switzerland), claimed to be effective for the treatment of male AGA [10]. The active ingredients contained in the product were chosen to obtain three main effects: proliferation of the stem cells of both the bulge and the dermal papilla, keratinization, and stimulation of microcirculation. Stem cell and dermal papilla stem cell proliferation was achieved by hydrolyzed rice protein and corosolic acid, respectively. Keratinization was stimulated by cysteine, lysine, and a glycoprotein (lectin). Microcirculation was stimulated by benzyl nicotinate. The mentioned results were obtained from studies commissioned by the company Labo Cosprophar AG, which has filed a patent (CH 703 390 B1) [10].

Materials and Methods

All the study procedures were carried out according to World Medical Association’s (WMA) Helsinki Declaration and its amendments (Ethical Principles for Medical Research Involving Human Subjects, adopted by the 18th WMA General Assembly Helsinki, Finland, June 1964 and amendments). To participate in the study, each participant was fully informed on study risks and benefits, aims, and procedures. An informed consent form and a consent release for publication of photos were signed by the subject prior to participating in the study.

Subjects and Study Design

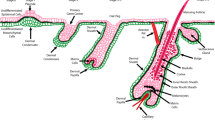

Healthy male volunteers suffering from alopecia grade II to IV according to the Hamilton–Norwood scale [11] (Fig. 1) were enrolled in the study. Subjects were enrolled in the study by a certified dermatologist if they fulfilled the inclusion and exclusion criteria laid down in the study design (Table 1) were applicable. Clinical examination was carried out in order to evaluate the degree and pattern of hair loss, and hair (length, diameter, and breakage) and scalp (inflammation, erythema and, scaling) conditions. Active and placebo treatments were then allocated by means of the Efron’s biased coin algorithm using PASS 11 (version 11.0.8 for Windows; PASS, LLC., Kaysville, UT, USA). The tested and the placebo products were used for 4 months according to the following procedure: apply one vial (5 mL) of the product on clean and dry scalp, line by line, concentrating on the areas where thinning is more evident; massage gently to aid penetration; apply every day for 5 consecutive days, stop the treatment for 2 days and then continue the application.

Tested Product

The tested product is a commercially available cosmetic lotion named Crescina® HFSC. The ingredients of the tested product and placebo are listed in Table 2.

Phototricogram

A transitional area of hair loss between normal hair and the balding area of 1.8 cm2 was defined using a stencil template and chosen for clipping. The clipped hairs within the target area were dyed for gray or fair hairs with a commercially available solution (RefectoCil®, GW Cosmetics GmbH, Leopoldsdorf, Germany) in order to enhance their contrast. Thereafter, the dyed hairs were cleansed using an alcoholic solution and digital images were taken while the area was still wet with a digital close-up camera. Images were taken at day 0, immediately after clipping, and 2 days after clipping. These two photographs were then examined by a software system that is able to recognize individual hair fibers in the photographs. By comparing the two photographs, the computer can determine which hairs are growing (anagen hairs) and which are not (telogen hairs). The same procedure was carried out after 2 and 4 months of treatment.

Pull Test

Gentle traction was exerted on a cluster of hairs (approximately 60 hairs) on at least three different areas of the scalp, and the number of extracted hairs was counted. Normally, less than three telogen-phase hairs should come out with each pull [12]. If at least three hairs were obtained with each pull or if more than ten hairs total were obtained, the pull test was considered positive and suggestive of telogen effluvium.

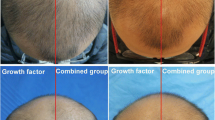

Global Photographic Assessment

Patients were asked to maintain the same hair style, color, and length throughout the study. Standardized global photographs of the frontal/parietal region were taken using a digital camera equipped with a macro lens.

Statistical Analysis

An intention to treat statistical analysis was performed using NCSS 8 (version 8.0.4 for Windows; NCCS, LLC., Kaysville, UT, USA). Data were checked for normality using either the Shapiro–Wilk W, Kolmogorov–Smirnov, and D’Agostino omnibus normality tests. If the data were normal, the repeated measure analysis of variance (RM-ANOVA) followed by Tukey–Kramer multiple comparison test was performed both for intra- and inter-group comparisons. If data were not normal, the Wilcoxon signed-rank test was performed for intra-group comparisons, whereas the Mann–Whitney U test was performed for inter-group comparisons. Values are expressed as arithmetic mean ± standard deviation (SD). P < 0.05 was considered significant.

Results

Forty-six healthy male volunteers (Table 3) suffering from alopecia grade II to IV were enrolled in the study.

Anagen

The results of anagen hair rates (as %) at baseline (T0), 2 (T2), and 4 (T4) months are reported in Table 4 and Fig. 2. Baseline mean anagen hair rate was similar between active (63.8 ± 4.2%) and placebo (62.8 ± 4.3%) groups, and not statistically significant (P > 0.05). At the 2 months follow-up, only the active product group demonstrated a statistically significant improvement of anagen hair rate (70.6 ± 6.9%); while in the placebo (63.7 ± 5.0%) group no changes were observed. At 4 months, the active product group showed an additional statistically significant increment of the mean anagen rate (74.5 ± 5.6%). A slight statistical improvement was also seen in the placebo group (65.0 ± 5.2%). The variation versus T0 (Fig. 3) of the anagen hair rate in the active product group was +6.8 and +10.7% after 2 and 4 months, respectively; whereas an improvement of +2.2% was seen in the placebo group only at 4 months. Statistical analysis of the mean anagen rate in the active group showed a time-dependent statistically significant improvement (P < 0.001); whereas in the placebo group, time was a source of variation only at 4 months (P = 0.004). Analysis of the mean anagen rate between the active group compared to the placebo group was also statistically significant (P < 0.001). The improvement of anagen rate in the active group was observed in 95.7% (at T2) and 100% (at T4) of the subjects participating in the trial; whereas in the placebo group it was seen in 56.5% (at T2) and 69.6% (at T4).

Pull Test

The results of pull testing at baseline, 2, and 4 months are reported in Table 5 and Fig. 4. Baseline mean pulled hairs in the pull test was similar between the active (9.2 ± 1.3) and placebo (9.1 ± 1.8) groups, which was not statistically significant (P > 0.05). At the 2 months follow-up, only the active product group demonstrated a statistically significant improvement of 29.6% of hair resistance to traction (6.4 ± 1.8); whereas in the placebo (8.3 ± 2.1) group no changes were observed. At 4 months, the active product group showed an additional statistically significant increment of 46.8% of hair resistance (4.8 ± 1.5). A slight statistical improvement of 16.6% was also seen in the placebo group (7.6 ± 1.9). Statistical analysis of the mean anagen rate in the active group showed a time-dependent statistically significant improvement (P < 0.001); whereas in the placebo group, time was a source of variation only at 4 months (P = 0.044). Analysis of the hair fall in the hair pull test between the active group compared to the placebo group was also statistically significant (P < 0.01 and P < 0.001 at T2 and T4, respectively). The improvement of hair resistance to traction in the active group was observed in 89.5% (at T2) and 100% (at T4) of the subjects participating in the trial; whereas in the placebo group it was seen in 52.6% (at T2) and 78.9% (at T4).

Global Photographic Assessment

Figure 5 shows the macroscopic effect of the product on hair growth. An increase in hair growth was seen in the frontal and parietal area (vertex) of the scalp.

Discussion

Androgenetic alopecia is the most common cause of hair loss among males and has a psychosociologic impact on the well-being of the subject [1]. The pharmacologic treatment of AGA is expensive, requires lifelong treatment, and may have side effects. Subjects are also reluctant/intimidated to use drugs for a nonpathologic condition; however, use of cosmetics is more acceptable.

A large number of cosmetics claiming to be effective in the coadjuvant treatment of AGA are sold on the market, but some lack proof of effect, relying only on the effects of the raw materials. Contrary to this approach, new cosmetic regulations [13] require manufactures to demonstrate product efficacy in order to protect subjects from misleading claims.

The present study aimed to assess the efficacy of the topical application of cysteine, lysine, a glycoprotein, hydrolyzed rice protein, and corosolic acid (the active ingredients that are contained in the formulation of Crescina® HFSC) in promoting hair growth and in decreasing hair loss [10]. It would be desirable to analyze a larger population sample; however, this would require longer-term studies (approximately 1 year), which are not always compatible with the needs of the economic commitment of research and the cosmetic market, which is rapidly and constantly developing. Moreover, the compliance of large groups of subjects who undergo the test decreases with time spent in the clinical trials. On this basis, as the present study has already shown efficacy in the short term (4 months), it was considered significant and important to highlight this positive result. The authors can further expand these data by considering a greater sample size and longer-term study.

In conclusion, the present investigation has demonstrated the effects of a mixture of ingredients that is able to promote hair growth and decrease hair loss. The results obtained showed that Crescina® HFSC applied for 4 months in subjects suffering from alopecia grade II to IV was effective in stimulating hair follicle activity as demonstrated by the time-dependent anagen rate increase. Correspondingly, the treatment decreased hair loss and hair resistance to traction, demonstrating its beneficial effect on hair loss.

References

Springer K, Brown M, Stulberg DL. Common hair loss disorders. Am Fam Physician. 2003;68:93–102.

Trueb RM. Molecular mechanism of androgenetic alopecia. Exp Gerontol. 2002;37:981–90.

Blume-Peytavi U. Anlagebedingter Haarausfall und aktuelle Therapiekonzepte. Akt Dermatol. 2002;28(Suppl. 1):19–23 (in German).

Gordon KA, Tosti A. Alopecia: evaluation and treatment. Clin Cosmet Investig Dermatol. 2011;4:101–6.

Mahe YF, Michelet JF, Billoni N, et al. Androgenetic alopecia and microinflammation. Int J Dermatol. 2000;39:576–84.

Hernandez BA. Is androgenic alopecia a result of endocrine effects on the vasculature? Med Hypotheses. 2004;62:438–41.

Kligman AM. The comparative histopathology of male-pattern baldness and senescent baldness. Clin Dermatol. 1988;6:108–18.

Paus R, Cotsarelis G. The biology of hair follicles. N Engl J Med. 1999;341:491–7.

Garza LA, Yang CC, Zhao T, et al. Bald scalp in men with androgenetic alopecia retains hair follicle stem cells but lacks CD200-rich and CD34-positive hair follicle progenitor cells. J Clin Invest. 2011;121:613–22.

Report patent document filed on January 13, 2012 in Zurich (CH) representative Schmauder & Partner AG Patent- und Markenanwalte VSP, Zurich.

Norwood OT. Male pattern baldness: classification and incidence. South Med J. 1975;68:1359–65.

Harrison S, Bergfeld W. Diffuse hair loss: its triggers and management. Clevel Clin J Med. 2009;76:361–7.

Regulation (EC) no 1223/2009 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 30 November 2009 on cosmetic products. Official Journal of the European Union. 2009; L342/59.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the staff of Farcoderm for their professionalism and support during study development. The performance of the study was sponsored by Labo Cosprophar AG, Basel, Switzerland. The sponsor had no influence in the performance, analysis, and interpretation of the study. Dr. Marzatico is the guarantor for this article, and takes responsibility for the integrity of the work as a whole.

Conflict of interest

Dr. Buonocore declares no conflict of interest. Dr. Nobile declares no conflict of interest. Dr. Michelotti declares no conflict of interest. Dr. Marzatico declares no conflict of interest.

Open Access

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and the source are credited.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 2.0 International License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

About this article

Cite this article

Buonocore, D., Nobile, V., Michelotti, A. et al. Clinical Efficacy of a Cosmetic Treatment by Crescina® Human Follicle Stem Cell on Healthy Males with Androgenetic Alopecia. Dermatol Ther (Heidelb) 3, 53–62 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1007/s13555-013-0021-2

Received:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s13555-013-0021-2