Abstract

With high rates of infant mortality in sub-Saharan Africa, investments in infant health are subject to tough prioritizations within the household, in which maternal preferences may play a part. How these preferences will affect infant mortality as African women have ever-lower fertility is still uncertain, as increased female empowerment and increased difficulty in achieving a desired gender composition within a smaller family pull in potentially different directions. I study how being born at a parity or of a gender undesired by the mother relates to infant mortality in sub-Saharan Africa and how such differential mortality varies between women at different stages of the demographic transition. Using data from 79 Demographic and Health Surveys, I find that a child being undesired according to the mother is associated with a differential mortality that is not due to constant maternal factors, family composition, or factors that are correlated with maternal preferences and vary continuously across siblings. As a share of overall infant mortality, the excess mortality of undesired children amounts to 3.3 % of male and 4 % of female infant mortality. Undesiredness can explain a larger share of infant mortality among mothers with lower fertility desires and a larger share of female than male infant mortality for children of women who desire 1–3 children. Undesired gender composition is more important for infant mortality than undesired childbearing and may also lead couples to increase family size beyond the maternal desire, in which case infants of the surplus gender are particularly vulnerable.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

I use the term “gender” in this article to refer to socially constructed aspects of male–female differences, and expectations of such differences, rather than biologically determined aspects (Haig 2004). Specifically, maternal preferences concern the gender of children whereas the sex of each child is registered in DHS surveys.

A model with all women is included in Online Resource 1, section F.

Section B of Online Resource 1 shows that similar patterns can be obtained when mothers who have experienced the death of a child are studied separately.

Section C of Online Resource 1 also includes interactions between maternal age and sibling composition.

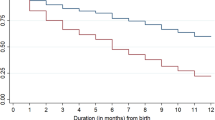

Infant mortality is here defined as deaths occurring to live born children until and including the 12th month of life, to include the many children who are reported to die at exactly 12 months due to heaping.

Alternative models are shown in Online Resource 1, section C.

References

Anderson, S., & Ray, D. (2010). Missing women: Age and disease. Review of Economic Studies, 77, 1262–1300.

Andersson, G., Hank, K., Rønsen, M., & Vikat, A. (2006). Gendering family composition: Sex preferences for children and childbearing behavior in the Nordic countries. Demography, 43, 255–267.

Arnold, F. (1992). Sex preference and its demographic and health implications. International Family Planning Perspectives, 18, 93–101.

Baird, S., Friedman, J., & Schady, N. (2010). Aggregate income shocks and infant mortality in the developing world. Review of Economics and Statistics, 93, 847–856.

Belanger, D. (2002). Son preference in a rural village in north Vietnam. Studies in Family Planning, 33, 321–334.

Bhat, P., & Zavier, A. (2003). Fertility decline and gender bias in northern India. Demography, 40, 637–657.

Black, R. E., Allen, L. H., Bhutta, Z. A., Caulfield, L. E., de Onis, M., Ezzati, M., . . . Rivera, J. (2008). Maternal and child undernutrition: Global and regional exposures and health consequences. Lancet, 371, 243–260.

Bongaarts, J. (1990). The measurement of wanted fertility. Population and Development Review, 16, 487–506.

Bongaarts, J. (1992). Do reproductive intentions matter? International Family Planning Perspectives, 18, 102–108.

Bongaarts, J. (2013). The implementation of preferences for male offspring. Population and Development Review, 39, 185–208.

Bongaarts, J., & Casterline, J. (2013). Fertility transition: Is sub-Saharan Africa different? Population and Development Review, 38, 153–168.

Bryant, J. (2007). Theories of fertility decline and the evidence from development indicators. Population and Development Review, 33, 101–127.

Caldwell, J. C. (1986). Routes to low mortality in poor countries. Population and Development Review, 12, 171–220.

Caldwell, J. C., & Caldwell, P. (1987). The cultural context of high fertility in sub-Saharan Africa. Population and Development Review, 13, 409–437.

Casterline, J. B., & El-Zeini, L. O. (2007). The estimation of unwanted fertility. Demography, 44, 729–745.

Casterline, J. B., & Sinding, S. W. (2000). Unmet need for family planning in developing countries and implications for population policy. Population and Development Review, 26, 691–723.

Chalasani, S., Casterline, J. B., & Koenig, M. A. (2008). Unwanted childbearing and child survival in Bangladesh. Unpublished manuscript, Department of Sociology, Pennsylvania State University, University Park, PA.

Chamarbagwala, R. (2011). Sibling composition and selective gender-based survival bias. Journal of Population Economics, 24, 935–955.

Coale, A. (1973). The demographic transition reconsidered. In Proceedings of the International Population Conference (pp. 53–77). Liège, Belgium: International Union for the Scientific Study of Population.

Croll, E. (2000). Endangered daughters: Discrimination and development in Asia. Abingdon, UK: Psychology Press.

Das Gupta, M. (1987). Selective discrimination against female children in rural Punjab, India. Population and Development Review, 13, 77–100.

Das Gupta, M., & Bhat, P. M. (1997). Fertility decline and increased manifestation of sex bias in India. Population Studies, 51, 307–315.

Dewey, K. G. (2003). Nutrient composition of fortified complementary foods: Should age-specific micronutrient content and ration sizes be recommended? Journal of Nutrition, 133, 2950–2952.

Flatø, M. (2017, October). Do mothers adjust their fertility preferences when having more children? Evidence from sub-Saharan Africa based on natural experiments. Paper presented at the International Union for the Scientific Study of Population (IUSSP) International Population Conference, Cape Town, South Africa.

Flatø, M., & Kotsadam, A. (2014). Droughts and gender bias in infant mortality in sub-Saharan Africa (Memorandum No. 02/2014). Oslo, Norway: Department of Economics, University of Oslo.

Garenne, M. (2003). Sex differences in health indicators among children in African DHS surveys. Journal of Biosocial Science, 35, 601–614.

Gipson, J. D., Koenig, M. A., & Hindin, M. J. (2008). The effects of unintended pregnancy on infant, child, and parental health: A review of the literature. Studies in Family Planning, 39, 18–38.

Grepin, K. A., & Bharadwaj, P. (2015). Maternal education and child mortality in Zimbabwe. Journal of Health Economics, 44, 97–117.

Guilmoto, C. Z. (2009). The sex ratio transition in Asia. Population and Development Review, 35, 519–549.

Günther, I., & Harttgen, K. (2016). Desired fertility and number of children born across time and space. Demography, 53, 55–83.

Haig, D. (2004). The inexorable rise of gender and the decline of sex: Social change in academic titles, 1945–2001. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 33, 87–96.

Imbens, G. W., & Lemieux, T. (2008). Regression discontinuity designs: A guide to practice. Journal of Econometrics, 142, 615–635.

Jayachandran, S. (2017). Fertility decline and missing women. American Economic Journal: Applied Economics, 9, 118–139

Jayachandran, S., & Pande, R. (2017). Why are Indian children so short? American Economic Review, 107, 2600–2629.

Johnson-Hanks, J. (2007). Natural intentions: Fertility decline in the African demographic and health surveys. American Journal of Sociology, 112, 1008–1043.

Jones, K. M. (2014). Growing up together: Cohort composition and child investment. Demography, 51, 229–255.

Joshi, S., & Schultz, T. (2013). Family planning and women’s and children’s health: Long-term consequences of an outreach program in Matlab, Bangladesh. Demography, 50, 149–180.

Khanna, R., Kumar, A., Vaghela, J. F., Sreenivas, V., & Puliyel, J. M. (2003). Community based retrospective study of sex in infant mortality in India. BMJ, 327(126). https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.327.7407.126

Kim, Y. S. (2010). The impact of rainfall on early child health (Job market paper). College Park, MD: University of Maryland.

Kravdal, Ø. (2002). Education and fertility in sub-Saharan Africa: Individual and community effects. Demography, 39, 233–250.

Kravdal, Ø., & Kodzi, I. (2011). Children’s stunting in sub-Saharan Africa: Is there an externality effect of high fertility? Demographic Research, 25(article 18), 565–594. https://doi.org/10.4054/DemRes.2011.25.18

Kravdal, Ø., Kodzi, I., & Sigle-Rushton, W. (2013). Effects of the number and age of siblings on educational transitions in sub-Saharan Africa. Studies in Family Planning, 44, 275–297.

Lartey, A. (2008). Maternal and child nutrition in sub-Saharan Africa: Challenges and interventions. Proceedings of the Nutrition Society, 67, 105–108.

Li, H., Yi, J., & Zhang, J. (2011). Estimating the effect of the one-child policy on the sex ratio imbalance in China: Identification based on the difference-in-differences. Demography, 48, 1535–1557.

Lightbourne, R. E. (1985). Individual preferences and fertility behaviour. In J. Cleland & J. Hobcraft (Eds.), Reproductive change in developing countries: Insights from the World Fertility Survey (pp. 165–198). Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press.

Milazzo, A. (2014). Why are adult women missing? Son preference and maternal survival in India (Policy Research Working Paper No. WPS6802). Washington, DC: World Bank.

Miller, G., & Urdinola, B. P. (2010). Cyclicality, mortality, and the value of time: The case of coffee price fluctuations and child survival in Colombia. Journal of Political Economy, 118, 113–155.

Mishra, V., Roy, T. K., & Retherford, R. D. (2004). Sex differentials in childhood feeding, health care, and nutritional status in India. Population and Development Review, 30, 269–295.

Montgomery, M. R., & Lloyd, C. B. (1996). Fertility and maternal and child health. In D. A. Ahlburg, A. C. Kelley, & K. Oppenheim Mason (Eds.), The impact of population growth on well-being in developing countries (pp. 37–66). Berlin, Germany: Springer.

Montgomery, M. R., Lloyd, C. B., Hewett, P. C., & Heuveline, P. (1997). The consequences of imperfect fertility control for children’s survival, health, and schooling (Demographic and Health Surveys Analytical Reports No. 7). Calverton, MD: Macro International.

Mosley, W. H., & Chen, L. C. (1984). An analytical framework for the study of child survival in developing countries. Population and Development Review, 10, 25–45.

Papay, J. P., Willett, J. B., & Murnane, R. J. (2011). Extending the regression-discontinuity approach to multiple assignment variables. Journal of Econometrics, 161, 203–207.

Pongou, R. (2013). Why is infant mortality higher in boys than in girls? A new hypothesis based on preconception environment and evidence from a large sample of twins. Demography, 50, 421–444.

Pongou, R. (2015). Sex differences in early-age mortality: The preconception origins hypothesis. Demography, 52, 2053–2056.

Reardon, S. F., & Robinson, J. P. (2012). Regression discontinuity designs with multiple rating-score variables. Journal of Research on Educational Effectiveness, 5, 83–104.

Rossi, P., & Rouanet, L. (2015). Gender preferences in Africa: A comparative analysis of fertility choices. World Development, 72, 326–345.

Sartorius, B., & Sartorius, K. (2014). Global infant mortality trends and attributable determinants: An ecological study using data from 192 countries for the period 1990–2011. Population Health Metrics, 12, 1–15. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12963-014-0029-6

Sen, A. (1990, December 20). More than 100 million women are missing. New York Review of Books. Retrieved from http://www.nybooks.com/articles/1990/12/20/more-than-100-million-women-are-missing/

Singh, A., Chalasani, S., Koenig, M. A., & Mahapatra, B. (2012). The consequences of unintended births for maternal and child health in India. Population Studies, 66, 223–239.

Smith-Greenaway, E., & Sennott, C. (2016). Death and desirability: Retrospective reporting of unintended pregnancy after a child’s death. Demography, 53, 805–834.

Timaeus, I. M., & Moultrie, T. A. (2008). On postponement and birth intervals. Population and Development Review, 34, 483–510.

United Nations Population Division. (2011). Sex differentials in childhood mortality (United Nations Publication No. ST/ESA/SER.A/314). New York, NY: United Nations.

United Nations Population Division. (2015). World population prospects: The 2015 revision, key findings and advance tables (Working Paper No. ESA/P/WP.241). New York, NY: United Nations.

van de Walle, E. (1992). Fertility transition, conscious choice, and numeracy. Demography, 29, 487–502.

Acknowledgments

The article has benefited from comments by seminar participants at the Wittgenstein Centre for Demography and Global Human Capital, Statistics Norway, and the University of Oslo. I would like to particularly thank Prashant Bharadwaj, Christophe Guilmoto, Nico Keilman, Andreas Kotsadam, Øystein Kravdal, Raya Muttarak, Martina Björkman Nyqvist, and three anonymous reviewers for helpful comments. While carrying out part of this research, I have been associated with the Centre for the Study of Equality, Social Organization, and Performance (ESOP) at the Department of Economics at the University of Oslo. ESOP is supported by the Research Council of Norway through its Centres of Excellence funding scheme, project number 179552. It has also partly been completed under the Systems Analysis Scholarship from the International Institute of Applied Systems Analysis and the South African National Research Foundation.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Electronic supplementary material

ESM 1

(PDF 254 kb)

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Flatø, M. The Differential Mortality of Undesired Infants in Sub-Saharan Africa. Demography 55, 271–294 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s13524-017-0638-3

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s13524-017-0638-3