Abstract

Some conservative groups argue that allowing same-sex couples to marry reduces the value of marriage to opposite-sex couples. This article examines how changes in U.S. legal recognition laws occurring between 1995 and 2010 designed to include same-sex couples have altered marriage rates in the United States. Using a difference-in-differences strategy that compares how marriage rates change after legal recognition in U.S. states that alter legal recognition versus states that do not, I find no evidence that allowing same-sex couples to marry reduces the opposite-sex marriage rate. Although the opposite-sex marriage rate is unaffected by same-sex couples marrying, it decreases when domestic partnerships are available to opposite-sex couples.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

For example, in June 2011, then–presidential candidate Rick Santorum stated that allowing same-sex couples to marry would “cheapen marriage and make it into something less valuable” (The Des Moines Register 2011). In 2004, James Dobson stated “[Gay people] want to destroy the institution of marriage. [Same-sex marriage] will destroy marriage” (Snyder 2004). The end-of-marriage argument was largely the rationale behind Proposition 8, the California state constitutional amendment that restricted marriage to a union between a man and a woman.

A few states in the third category allow opposite-sex couples to enter into civil unions and domestic partnerships if at least one member of the couple is at least 62 years old. Results are robust to the inclusion of the laws separately. I combine the laws because the coefficients on the two types of laws are similar if I estimate the effects separately, likely because marriage rates are driven by young people.

Colorado allows people to designate beneficiaries. Because these types of unions do not imply a romantic relationship—that is, any two unmarried people can enter into designated beneficiary agreements, including friends and siblings—and do not offer most of the benefits of marriage, I do not code Colorado as providing alternate recognition. All results are robust to the omission of Colorado or the estimation of a separate coefficient for the effect of designated beneficiary agreements. As of May 2013, Colorado offers more comprehensive civil unions exclusively to same-sex couples.

For a detailed example of a domestic partnership law, see the American Civil Liberty Union’s guide to civil unions in Illinois, which is available online (http://civilunions.aclu-il.org/).

For a complete listing of federal benefits of marriage, see Shah (2011).

Because the District of Columbia does not keep statistics on the number of same-sex marriages, I omit it from the analysis of opposite-sex marriages after same-sex couples can marry there.

I omit same-sex couples from the sample as well as any couples whose gender or marital status changed. Before 2010, the CPS changed the sex of the spouse if two people of the same sex reported being married. Beginning in 2010, the CPS changed the marital status. The results are very similar if I do not try to account for same-sex couples.

Wolfers (2006) used a similar econometric model to study the effects of divorce laws.

These marriages would typically not be legally recognized in non–same-sex marriage states because of DOMA.

The results are very similar if the dependent variable is adjusted so that it no longer accounts for population and is instead the log of marriage rates in a state and year.

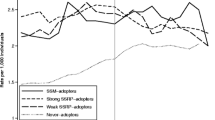

These estimates do not control for demographic characteristics. The graph looks similar when demographic controls are included.

As discussed earlier, one might expect different responses for people with different political attitudes. I tested for different reactions to the Massachusetts ruling for more-liberal and more-conservative states as measured by the percentage of the state population that voted for George W. Bush in 2004, which is the year when Massachusetts began allowing same-sex couples to marry and when one of the main issues in the presidential election was a federal Constitutional ban on allowing same-sex couples to marry. Bush supported the ban, while his opponent, John Kerry, did not. I found no evidence of differences.

The new set of control states is Delaware, Illinois, Indiana, Minnesota, New Mexico, New York, North Carolina, Pennsylvania, Rhode Island, West Virginia, and Wyoming.

An alternate method of choosing the control group is to use the synthetic control method from Abadie et al. (2010), which selects control groups that do not violate the parallel trends assumption. In results not shown (but available upon request), I implemented the synthetic control method for each state that has changed its legal recognition laws. The results from the synthetic control method were consistent with the results presented throughout this article. I found no evidence that allowing same-sex couples to marry reduces the opposite-sex marriage rates, but I did find evidence that marriage rates fall when opposite-sex couples can enter into the new forms of recognition.

References

Abadie, A., Diamond, A., & Hainmueller, J. (2010). Synthetic control methods for comparative case studies: Estimating the effect of California’s Tobacco Control Program. Journal of the American Statistical Association, 105, 493–505.

Becker, G. S. (1973). A theory of marriage: Part I. Journal of Political Economy, 81, 813–846.

Becker, G. S. (1974). A theory of marriage: Part II. Journal of Political Economy, 82, S11–S26.

Besley, T., & Burgess, R. (2004). Can labor regulation hinder economic performance? Evidence from India. Quarterly Journal of Economics, 119, 91–134.

Bitler, M. P., Gelbach, J. B., Hoynes, H. W., & Zavodny, M. (2004). The impact of welfare reform on marriage and divorce. Demography, 41, 213–236.

Brien, M. J., Dickert-Conlin, S., & Weaver, D. A. (2004). Widows waiting to wed? (Re)Marriage and economic incentives in Social Security widow benefits. The Journal of Human Resources, 39, 585–623.

Dillender, M. (2013). Essays on health insurance and the family (Unpublished doctoral dissertation). Department of Economics, University of Texas, Austin.

Glaeser, E. L., & Sacerdote, B. I. (2008). Education and religion. Journal of Human Capital, 2, 188–215.

Jones, J. M. (2013, May 13). Same-sex marriage support solidifies above 50% in U.S. Gallup Politics. Retrieved from http://www.gallup.com/poll/162398/sex-marriage-support-solidifies-above.aspx

Kreider, R. M., & Ellis, R. (2011). Number, timing, and duration of marriages and divorces: 2009 (Current Population Reports P70-125). Washington, DC: U.S. Census Bureau.

Kurtz, S. (2004, June 3). No explanation. National Review Online. Retrieved from http://www.nationalreview.com/articles/210906/no-explanation/stanley-kurtz

Langbein, L., & Yost, M. (2009). Same-sex marriage and negative externalities. Social Science Quarterly, 90, 292–308.

Pew Research Center. (2013). Growing support for gay marriage: Changed minds and changing demographics (Report). Washington, DC: Pew Research Center. Retrieved from http://www.people-press.org/2013/03/20/growing-support-for-gay-marriage-changed-minds-and-changing-demographics/

Rauch, J. (2004). Gay marriage: Why it is good for gays, good for straights, and good for America. New York, NY: Times Books.

Shah, D. K. (2011). Defense of Marriage Act: Update to prior report. Washington, DC: U.S. Government Accounting Office. Retrieved from http://www.gao.gov/new.items/d04353r.pdf

Snyder, C. P. (2004, October 23). Marriage, family advocate in state to support Coburn. The Oklahoman. Retrieved from http://newsok.com/article/2871070

The Des Moines Register. (2011, June 27). Santorum: Same-sex marriage undermines marriage, faith. Retrieved from http://caucuses.desmoinesregister.com/2011/06/27/santorum-same-sex-marriage-undermines-marriage-faith/

Trandafir, M. (2013). The effect of same-sex marriage laws on different-sex marriage: Evidence from the Netherlands. Demography. Advance online publication. doi:10.1007/s13524-013-0248-7

Wolfers, J. (2006). Did unilateral divorce laws raise divorce rates? A reconciliation and new results. American Economic Review, 96, 1802–1820.

Acknowledgments

This work was completed as part of my dissertation at the University of Texas at Austin. I thank the Editors, multiple anonymous referees, Jason Abrevaya, Sandra Black, Daniel Hamermesh, Carolyn Heinrich, Gerald Oettinger, and Stephen Trejo for helpful comments.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Dillender, M. The Death of Marriage? The Effects of New Forms of Legal Recognition on Marriage Rates in the United States. Demography 51, 563–585 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1007/s13524-013-0277-2

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s13524-013-0277-2