Abstract

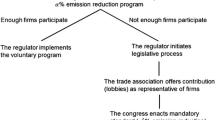

This article demonstrates the explanatory power of an expanded policy stream, as part of Kingdon’s Multiple Streams Framework. Product substitutes, corporate social responsibility, the global economy, and the market maverick rationalize the incentives under which regulators, consumers, businesses, and environmental NGOs interact to explain the formation of two landmark voluntary programs on mercury and arsenic use, respectively. Arsenic and mercury are ranked first and third, respectively, on the US Environmental Protection Agency’s priority list of hazardous substances. In both cases, the existence of a product substitute that performed on par with the original product but generated less negative environmental impact motivated the private sector to go beyond compliance in their environmental management. Notwithstanding, the push and pull of variables in the problem, politics, and policy streams, and the interplay of diverse actors led to the emergence of diverse forms of voluntary programs. In the mercury case, an industry association steered the technocratic process of the chlor-alkali industry’s voluntary stewardship program, which led to marginal reductions in toxic chemical use, as part of the global phase-out of mercury already under way. By contrast, in the arsenic case, an environmental activist campaign successfully compelled the pressure-treated wood industry to concede to a voluntary cancelation of chromated copper arsenate, an arsenic compound, in residential uses. Subsequently, arsenic use fell to levels not seen since the 1920s. In both cases, strong coalition building—the former by businesses and the latter by environmental NGOs—combined with a fragmented or nonexistent opposing side shaped the final form of each voluntary program.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

Alternative and nonregulatory governance approaches include information-based regulations (e.g., EPA’s Toxic Release Inventory), collaborative partnerships (e.g., regional watershed partnerships), market-based approaches (e.g., SO2 trading, catch shares in fisheries), and voluntary programs (e.g., EPA’s 33/50 program, the Chemical Industry’s Responsible Care). This paper is primarily concerned with voluntary programs, which encourage firms and industries to engage in beyond-compliance actions without the force of law.

Source: https://www.atsdr.cdc.gov/spl/resources/ATSDR_2017_Full_SPL_Spreadsheet.xlsx. Lead, which is ranked second on the priority list, is not a part of this study because lead has not been a subject of a voluntary agreement negotiated between the government and private industry.

The ACF answers questions about how people mobilize, maintain, and act in advocacy coalitions, how people learn, and how scientists and technical information are incorporated into the policy process (Weible and Ingold 2018; Weible et al. 2009). On the other hand, Punctuated Equilibrium theory explains the observation that political processes are generally characterized by stability and incrementalism, but occasionally they produce dramatic departures from the past (Baumgartner et al. 2018; Baumgartner and Jones 1993; Baumgartner et al. 2009). Furthermore, Social Construction theory emphasizes the ways in which policy problems and target populations are socially constructed to explain why some groups are advantaged more than others and how policy designs reinforce or alter such advantages (Schneider and Ingram 1993; Schneider and Sidney 2009).

This paper follows Zahariadis (2007) to posit that stream independence is a conceptual devise rather an assumption about empirical reality. It has the advantage of enabling researchers to uncover rather than assume rationality, i.e., it allows for the fact that sometimes policies are in search of a rationale or they solve no problems.

These incentives could come from the politics stream as corporate actors engage in voluntary compliance to avoid being the targets of private and public politics (see “Politics stream”).

This discussion pertains to the supply side of the global economy. The demand side is the rising consumer demand for “green” products in market competition.

Interview protocol is available upon request from the author.

In an interview, the former director of the Chlorine Institute said that it was difficult to measure emissions from a process he described as “‘football field-sized’ lines of 30 to 50 mercury-cells, each holding 10,000 pounds of mercury (Johnson 1999).”

Interview quote by an environmental manager of a mercury-cell plant.

Interview quote by EPA Regional 5 office staff scientist #1.

The characterization of an “improved” relationship was expressed by the former director of the Chlorine Institute, a Chlorine Institute member firm representative, and two EPA regulators during interviews.

Interview quote by EPA Regional 5 office staff scientist #3.

This characterization of the relationship between industry, regulators, and NGO activists were expressed widely by NGO informants who regularly participated in GLBTS stakeholder meetings.

This information was shared with the author by the former director of the Chlorine Institute and by staff scientist #3 at the EPA Regional 5 office, as well as confirmed on the EPA website.

Industry news wires reported about the chlor-alkali industry’s voluntary reductions as an act of CSR. See “Olin to end Hg releases from chlor-alkali plants,” April 29, 1999, Chemical & Engineering News.

Interview quote by a former CPSC senior administrator.

Ibid.

Interview quote by a staff scientist at the EPA’s Office of Pesticide Program.

The largest arsenic end-user was the pressure-treated wood industry (88%), agriculture (4%), glass (4%), and semiconductor (4%) industries (“USGS Minerals Information” 2012).

In 2002, EPA awarded the “Designing Greener Chemicals Award” to the manufacturer of ACQ (see https://www.epa.gov/greenchemistry/presidential-green-chemistry-challenge-2002-designing-greener-chemicals-award). This information was also independently shared with the author by (1) independent consultant who conducted an independent assessment of ACQ, (2) coordinator of the NGO activist campaign, and (3) staff scientist at the EPA Office of Pesticide Program’s Antimicrobials Division.

Information shared by a NGO activist in an interview.

Interview quote by the president of the wood treatment company that switched to ACQ.

The president of the wood treatment company claimed that his company did not receive discounts on ACQ from the chemical manufacturer before or after his company’s switch to ACQ.

Interview quote by a University of Miami professor who served as an expert scientist in the SAP.

References

Aberbach JD, Christensen T (2014) Why reforms so often disappoint. Am Rev Public Adm 44(1):3–16. https://doi.org/10.1177/0275074013504128

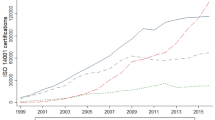

Arimura TH, Darnall N, Katayama H (2011) Is ISO 14001 a gateway to more advanced voluntary action? The case of green supply chain management. J Environ Econ Manag 61(2):170–182

Arora S, Cason TN (1995) An experiment in voluntary environmental regulation: participation in EPA’s 33/50 Program. J Environ Econ Manag 28(3)271–286

Ayres R (1997) The life-cycle of chlorine, part I: chlorine production and the chlorine-mercury connection. J Ind Ecol 1(1):81–94

Baron DP (2001) Private politics, corporate social responsibility, and integrated strategy. Journal of Economics & Management Strategy 10(1):7–45

Baron DP (2005) Competing for the public through the news media. Journal of Economics & Management Strategy 14(2):339–376

Baron DP (2008) Managerial contracting and corporate social responsibility. J Public Econ 92(1–2):268–288

Baron DP (2009) A positive theory of moral management, social pressure, and corporate social performance. Journal of Economics & Management Strategy 18(1):7–43. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1530-9134.2009.00206.x

Baron DP (2010) Morally motivated self-regulation. Am Econ Rev 100(4):1299–1329. https://doi.org/10.1257/aer.100.4.1299

Baron DP, Diermeier D (2007) Strategic activism and nonmarket strategy. Journal of Economics & Management Strategy 16(3):599–634. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1530-9134.2007.00152.x

Baumgartner FR, Jones BD (1993) Agendas and instability in American politics, 1st edn. University of Chicago Press

Baumgartner FR, Breunig C, Green-Pedersen C, Jones BD, Mortensen PB, Nuytemans M, Walgrave S (2009) Punctuated equilibrium in comparative perspective. Am J Polit Sci 53(3):603–620. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-5907.2009.00389.x

Baumgartner FR, Jones BD, Mortensen PB (2018) Punctuated equilibrium theory: explaining stability and change in public policymaking. In: Weible CM, Sabatier PA (eds) Theories of the policy process, 4th edn. Westview Press, Boulder, pp 55–102

Becker-Olsen KL, Andrew Cudmore B, Hill RP (2006) The impact of perceived corporate social responsibility on consumer behavior. J Bus Res 59(1):46–53

Béland D, Howlett M (2016) The role and impact of the multiple-streams approach in comparative policy analysis. Journal of Comparative Policy Analysis: Research and Practice 18(3):221–227. https://doi.org/10.1080/13876988.2016.1174410

Besley T, Ghatak M (2007) Retailing public goods: the economics of corporate social responsibility. J Public Econ 91(9):1645–1663

Bi X, Khanna M (2012) Reassessment of the impact of the EPA’s voluntary 33/50 program on toxic releases. Land Econ 88(2):341–361

Birkland, Thomas A. 1997. After disaster: agenda setting, public policy, and focusing events. Georgetown University Press

Birkland TA (1998) Focusing events, mobilization, and agenda setting. Journal of Public Policy 18(1):53–74

Blair B, Zimny-Schmitt D, Rudd MA (2017) U.S. news media coverage of pharmaceutical pollution in the aquatic environment: a content analysis of the problems and solutions presented by actors. Environ Manag 60(2):314–322. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00267-017-0881-9

Borck J, Coglianese C (2009) Voluntary environmental programs: assessing their effectiveness. Annual Review of Environment & Resources 34(1):305

Buthe T (2004) Governance through private authority: non-state actors in world politics. J Int Aff 58(1):281–290

Buthe T (2010) Global private politics: a research agenda. Business & Politics 12(3):1–24

Buthe T, Mattli W (2011) New global rulers: the privatization of regulation in the world economy. Princeton University Press, Princeton

Coglianese C (2008) Managerial turn in environmental policy, the. New York University Environmental Law Journal 17:54

Coglianese C, Nash J (2006) Leveraging the private sector : management-based strategies for improving environmental performance. Resources for the Future, Washington, D.C.

CPSC (2003) “Briefing package: petition to ban chromated copper arsenate (CCA)-treated wood in playground equipment (petition HP 01–3).” U.S. Consumer Product Safety Commission. http://www.cpsc.gov/library/foia/foia03/brief/cca0.pdf

Cutler A (1999) Private authority and international affairs. State University of New York Press, Albany

Dardis FE, Baumgartner FR, Boydstun AE, De Boef S, Shen F (2008) Media framing of capital punishment and its impact on individuals’ cognitive responses. Mass Commun Soc 11(2):115–140

Davidson SL, de Loë RC (2016) The changing role of ENGOs in water governance: institutional entrepreneurs? Environ Manag 57(1):62–78. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00267-015-0588-8

Fiack D, Kamieniecki S (2017) Stakeholder engagement in climate change policymaking in American cities. J Environ Stud Sci 7(1):127–140. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13412-014-0205-9

GAO (2007) “Chemical Regulation: Comparison of U.S. and Recently Enacted European Union Approaches to Protect against the Risks of Toxic Chemicals.” Report to Congressional Requesters GAO-07-825. U.S. Government Accountability Office. http://www.gao.gov/new.items/d07825.pdf

Gereffi G (1999) International trade and industrial upgrading in the apparel commodity chain. J Int Econ 48(1):37–70

Gereffi G, Humphrey J, Sturgeon T (2005) The governance of global value chains. Rev Int Polit Econ 12(1):78–104. https://doi.org/10.1080/09692290500049805

Gerring J, Seawright J (2007) “Techniques for choosing cases.” In case study research: principles and practices, 86–150. Cambridge University Press

Grandjean P, Weihe P, White RF, Debes F, Araki S, Yokoyama K, Murata K, SØRENSEN N, Dahl R, Jørgensen PJ (1997) Cognitive deficit in 7-year-old children with prenatal exposure to methylmercury. Neurotoxicol Teratol 19(6):417–428. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0892-0362(97)00097-4

Herweg N, Zahariadis N, Zohlnhofer R (2018) The multiple streams framework: foundations, refinements, and empirical applications. In: Weible CM, Sabatier PA (eds) Theories of the policy process, 4th edn. Westview Press, Boulder, pp 17–54

Howlett M, McConnell A, Perl A (2016) Weaving the fabric of public policies: comparing and integrating contemporary frameworks for the study of policy processes. Journal of Comparative Policy Analysis: Research and Practice 18(3):273–289. https://doi.org/10.1080/13876988.2015.1082261

Howlett M, McConnell A, Perl A (2017) Moving policy theory forward: connecting multiple stream and advocacy coalition frameworks to policy cycle models of analysis. Aust J Public Adm 76(1):65–79. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-8500.12191

Hsueh L (2013) Beyond regulations: industry voluntary ban in arsenic use. J Environ Manag 131:435–446. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvman.2013.09.042

Hsueh L, Prakash A (2012a) Incentivizing self-regulation: federal vs. state-level voluntary programs in US climate change policies. Regulation & Governance 6(4):445–473

Hsueh L, and Aseem P (2012b). “Private voluntary programs on climate change: U.S. federal government as the sponsoring actor.” In: Karsten R (eds) Business and climate policy: The potentials and pitfalls of private voluntary programs, 77–110. United Nations University Press

Jenkins-Smith HC, Nohrstedt D, Weible CM, Ingold K (2018) The advocacy coalition framework: an overview of the research program. In: Weible CM, Sabatier PA (eds) Theories of the policy process, 4th edn. Westview Press, Boulder

Johnson J (1999) Olin to end hg releases from Chlor-alkali plants. C&EN 26:1999

Khanna M, Damon LA (1999) EPA’s voluntary 33/50 program: impact on toxic releases and economic performance of firms. J Environ Econ Manag 37(1):1–25

Kingdon J (1984) Agendas, alternatives, and public policies. Little Brown, Boston

Kingdon J (1995) Agendas, alternatives, and public policies, 2nd edn. Longman, New York

Kinsey J, Anscombe FR, Lindberg SE, Southworth GR (2004) Characterization of the fugitive mercury emissions at a chlor-alkali plant: overall study design. Atmos Environ 38(4):633–641

Kitzmueller M, Shimshack J (2012) Economic perspectives on corporate social responsibility. J Econ Lit 50(1):51–84

Koontz T (2004) Collaborative environmental management : what roles for government? Resources for the Future, Washington DC

Lyon TP, Maxwell JW (2004) Corporate environmentalism and public policy. Cambridge, Cambridge University Press

Lyon TP, Maxwell JW (2007) Environmental public voluntary programs reconsidered. Policy Stud J 35(4):723–750. https://doi.org/10.1111/%28ISSN%291541-0072/issues

Lyon TP, Maxwell JW (2008) Corporate social responsibility and the environment: a theoretical perspective. Rev Environ Econ Policy 2(2):240–260. https://doi.org/10.1093/reep/ren004

Matten D, Moon J (2005) A conceptual framework for understanding CSR. In: Habisch A, Jonker J, Wegner M, Schmidpeter R (eds) Corporate social responsibility across Europe. Springer, Berlin, Heidelberg

May PJ (1991) Reconsidering policy design: policies and publics. Journal of Public Policy 11(02):187–206

Michaels S, Goucher NP, McCarthy D (2006) Policy windows, policy change, and organizational learning: watersheds in the evolution of watershed management. Environ Manag 38(6):983–992. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00267-005-0269-0

Mintrom M, Norman P (2009) Policy entrepreneurship and policy change. Policy Stud J 37(4):649–667. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1541-0072.2009.00329.x

Mockrin MH, Fishler HK, Stewart SI (2018) Does wildfire open a policy window? Local government and community adaptation after fire in the United States. Environ Manag 62(2):210–228. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00267-018-1030-9

Morgenstern RD, Pizer WA (2007) Reality check: the nature and performance of voluntary environmental programs in the United States, Europe, and Japan. Washington, Resources for the Future

Mukherjee I, Howlett M (2015) Who is a stream? Epistemic communities, instrument constituencies and advocacy coalitions in public policy-making. Politics and Governance 3(2):65–75. https://doi.org/10.17645/pag.v3i2.290

O’Neill K (2000) Waste trading among rich nations: building a new theory of environmental regulation. Cambridge, MIT Press

Platt B, Lent T, Walsh B (2005) “The healthy building network’s guide to plastic lumber.” https://www.greenbiz.com/sites/default/files/document/CustomO16C45F64528.pdf

Potoski M, Prakash A (2009) Information asymmetries as trade barriers: ISO 9000 increases international commerce. Journal of Policy Analysis and Management 28(2):221–238

Prakash A, Potoski M (2006) The voluntary environmentalists: Green clubs, ISO 14001, and voluntary regulations. Cambridge, Cambridge University Press

Prakash A, Potoski M (2007) Investing up: FDI and the cross-country diffusion of ISO 14001 management systems. Int Stud Q 51(3):723–744

Pralle S (2006) Branching out, digging in: environmental advocacy and agenda setting. Georgetown University Press, Washington D.C.

Pralle S (2010) “Shopping around: environmental organizations and the search for policy venues.” In Aseem Prakash and Mary Kay Gugerty (eds) Advocacy Organizations and Collective Action, 177–201. Cambridge University Press

Rabe BG (2007) Beyond Kyoto: climate change policy in multilevel governance systems. Governance 20(3):423–444. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-0491.2007.00365.x

Rabe BG (2010) The aversion to direct cost imposition: selecting climate policy tools in the United States. Governance 23(4):583–608. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-0491.2010.01499.x

Revesz RL (1992) Rehabilitating interstate competition: rethinking the race-to-the-bottom rationale for federal environmental regulation. N Y Univ Law Rev 67:1210

Ridde V (2009) Policy implementation in an African state: an extension of Kingdon’s multiple-streams approach. Public Adm 87(4):938–954. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9299.2009.01792.x

Schneider A, Ingram H (1993) Social construction of target populations: implications for politics and policy. Am Polit Sci Rev 87(2):334–347

Schneider A, Sidney M (2009) What is next for policy design and social construction theory?1. Policy Stud J 37(1):103–119. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1541-0072.2008.00298.x

Snyder LD, Miller NH, Stavins RN (2003) The effects of environmental regulation on technology diffusion: the case of chlorine manufacturing. Am Econ Rev 93(2):431–435

Solecki WD, Michaels S (1994) Looking through the postdisaster policy window. Environ Manag 18(4):587–595. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02400861

Stone DA (1989) Causal stories and the formation of policy agendas. Political Science Quarterly 104(2):281–300

“USGS Minerals Information” (2012) 2012. http://minerals.usgs.gov/minerals/

Vidovic M, Khanna N (2007) Can voluntary pollution prevention programs fulfill their promises? Further evidence from the EPA’s 33/50 program. J Environ Econ Manag 53(2):180–195

Vogel D (2005) The market for virtue: the potential and limits of corporate social responsibility. Brookings Institution Press, Washington, D.C.

Vogel D (2010) The private regulation of global corporate conduct: achievements and limitations. Bus Soc 49(1):68–87

Vogel D, Kagan RA (2004) Dynamics of regulatory change: how globalization affects national regulatory policies. Oakland, University of California Press

Watts R, Maddison J (2012) The role of media actors in reframing the media discourse in the decision to reject relicensing the Vermont Yankee nuclear power plant. J Environ Stud Sci 2(2):131–142. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13412-011-0066-4

Weible CM, Ingold K (2018) Why advocacy coalitions matter and practical insights about them. Policy Polit 46(2):325–343. https://doi.org/10.1332/030557318X15230061739399

Weible CM, Sabatier PA, McQueen K (2009) Themes and variations: taking stock of the advocacy coalition framework. Policy Stud J 37(1):121–140. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1541-0072.2008.00299.x

Zahariadis N (2003) Ambiguity and choice in public policy: political decision making in modern democracies. Washington, Georgetown University Press

Zahariadis N (2007) The multiple streams framework: Structure, limitations, prospects. In: Sabatier P (ed) Theories of policy process, 2nd edn. Westview Press, Boulder

Zahariadis N (2014) Ambiguity and multiple streams. In: Weible CM, Sabatier PA (eds) Theories of the policy process, 3rd edn. Westview Press, Boulder

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Appendix

Appendix

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Hsueh, L. Expanding the multiple streams framework to explain the formation of diverse voluntary programs: evidence from US toxic chemical use policy. J Environ Stud Sci 10, 111–123 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s13412-020-00600-1

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s13412-020-00600-1