Abstract

Previous ion mobility (IM) studies have demonstrated that varying the drift gas composition can be used to enhance chemical selectivity and resolution, yet there are few drift gas studies aimed at achieving quantitatively reproducible mobility measurements. Here, we critically evaluate the conditions necessary to achieve reproducible collision cross section (CCS) measurements in pure drift gases (helium, nitrogen, argon, and carbon dioxide) using a commercial uniform field drift tube instrument. Optimal experimental parameters are assessed based on the convergence of CCS measurements to reproducible values which are compared with literature values. A suite of calibration standards with diverse masses, biological classes, and charge states are examined to assess chemical selectivity and resolution achievable in each drift gas. Results indicate nitrogen and argon perform similarly and are sufficient for most applications where high resolving power and high peak capacity are desired. Carbon dioxide exhibits more selectivity for resolving structurally heterogeneous compounds, which may be preferable in specific analyte pair separations. Helium demonstrated modest separation capabilities but has utility for comparison to theoretical values and previously published work. In drift gases other than nitrogen, pressure differentials up to 230 mTorr between the drift tube and upstream chamber were optimal for improving correlation to literature values, while in nitrogen, the recommended pressure differential of 150 mTorr was found appropriate. We present recommended experimental parameters as well as gas-specific CCS measurements for structurally homogeneous sets of analytes which are suitable for use by other laboratories as standards for purposes of instrument calibration and overall assessment of IM separation performance.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Ion mobility (IM) spectrometry is an important analytical technique for the rapid separation and identification of a wide variety of chemical compounds [1,2,3,4,5,6]. In a conventional drift tube, the separation of chemical species results from numerous, near-thermal collisions between analyte ions and a chemically inert drift gas. Total IM separation times occur on the order of milliseconds, and thus are both high throughput and sufficiently fast to allow for integration with other analytical separation techniques [7, 8]. Whereas in conventional gas and liquid phase chromatography, it is well established that the chemical selectivity of the separation can be enhanced by choosing different stationary phases, IM is more appropriately described as a gas-phase electrophoretic technique, and as such does not incorporate a stationary phase. Instead, varying the drift gas composition has been demonstrated to affect separation efficiency in a similar manner as changing solvent conditions in capillary electrophoresis to tune separation selectivity. Most notably in high-field IM techniques such as high-field asymmetric waveform ion mobility spectrometry (FAIMS) and differential mobility spectrometry (DMS), the carrier gas composition is commonly altered to increase the resolution for closely spaced analytes [9,10,11,12,13,14]. For conventional low-field IM techniques such as drift tube (DTIMS) and traveling wave (TWIMS), this practice is less common, although several notable cases exist [15,16,17]. For example, seminal work from Hill and coworkers demonstrated enhanced analyte selectivity on an ambient pressure drift tube when varying the drift gas from low to high polarizability (helium, nitrogen, argon, and carbon dioxide) [18,19,20,21]. Eberlin and coworkers reported improved separation of isomeric haloanilines, carbohydrates, and petroleum constituents when operating a traveling wave instrument in CO2 as opposed to conventional N2 gas [22,23,24,25]. Recently, Yost and coworkers demonstrated increased resolving power for several isobaric steroids, analyzed in a reduced-pressure drift tube instrument, using CO2 as the drift gas [26]. In many cases, however, the more polarizable drift gases (e.g., Ar, CO2, and N2O) are not reported to dramatically improve the overall IM peak capacity and resolution for chemically similar analytes, including peptides, amino acids, structural isomers, and protein conformers, in comparison to He or N2 drift gases [27,28,29,30]. A large survey of various drift gases (He, N2, Ar, CO2, N2O, SF6) recently conducted on a commercial drift tube instrument by Fjeldsted and coworkers investigated the separation of isomeric carbohydrates, fluoroalkyl phosphazenes, and various small-molecule pesticides. Higher resolution was generally observed for drift gases with access to the highest resolving powers in the instrumentation, namely conventional He and N2. Some enhanced selectivity and resolution were observed for the more polarizable drift gases (CO2, N2O, and SF6), although results were specific to the analyte pairs being investigated [31]. The literature examining the roles various drift gases play on IM separation capabilities are complicated and must be taken case-by-case. Given the potential analytical power that the drift gas composition can play in enhancing the IM resolution, there is a need for exploring IM separations in alternate drift gases across a broader range of analytes and reporting quantitatively comparable metrics of separation capabilities obtained from various laboratories. To accomplish this, a common framework for acquiring and comparing ion mobility data obtained in different drift gases needs to be established.

In addition to providing analyte structural information, collision cross section (CCS) values are useful for comparing IM measurements obtained using different IM instrumentation and techniques [1, 32,33,34] and recently have been used as an additional molecular description combined with accurate mass and retention time information for high confidence identification of unknowns arising from complex samples [33, 35,36,37,38,39]. While some fundamental work has been done using matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization (MALDI) [40, 41], the majority of CCS measurements have been conducted using electrospray ionization (ESI), including the work here. For alternate drift gas work, separations conducted across different instrument platforms, such as drift tube and traveling wave, cannot be directly compared without utilizing a normalized measurement such as CCS [32]. Comparisons of IM separation performance are hindered by the fact that a majority (95%) of CCS measurements have been reported only in conventional He and N2 drift gases [1]. In addition to the general lack of reporting CCS measurements in alternate drift gas work, a large-scale study of the effects of drift gas on a wide mass range, multiple biological classes, and varying charge states has yet to be accomplished. In this work, we investigate four of the most commonly used drift gases, helium (He), nitrogen (N2), argon (Ar), and carbon dioxide (CO2), and establish instrument conditions necessary to achieve high reproducibility and enhanced separation efficiency for diverse sets of structurally homogeneous analytes representing various charge states and chemical classes. We assess the separation efficiency in each gas using a combination of single-peak resolving power, two-peak resolution, and peak capacity, and provide detailed reporting of the CCS measured in each drift gas for low-field DTIMS.

Methods

Instrumentation

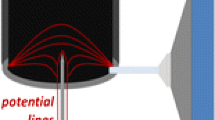

A commercial drift tube ion mobility–mass spectrometer (6560, Agilent Technologies) equipped with a thermally assisted electrospray ionization source (Jet Stream, Agilent) was used for all measurements described herein [42]. The drift gases used were high-purity N2, He, Ar, and CO2 (Air Liquide). N2, He, and Ar were UHP grade supplied at 99.999% purity, whereas CO2 was Coleman grade, at 99.99% purity. The high-pressure funnel (HPF), trap funnel (TF), and drift tube (DT) regions of the instrument, shown in the schematic in Figure 1, were supplied with either He, N2, Ar, or CO2 using a commercially upgraded drift gas manifold (Alternate Gas Kit, Agilent). Briefly, the gas kit consists of a precision closed-loop pressure controller (640B, MKS Instruments) which makes real-time adjustments to the pressures based on readings from a capacitance manometer (CDG-500, Agilent) mounted on the DT chamber. Prior to being directed into the instrument, each drift gas was passed through a passive purifier specific for: He or Ar (RMSH-4, Agilent), N2 (RMSN-4, Agilent), or CO2 (P600-2, VICI Metronics). Instrument tuning utilized the vendor autotune function in standard mass range (m/z 3200 mode). For He, tuning was performed in N2 before switching to He to mitigate issues related to gas breakdown at high voltage, manifesting as uncorrelated low m/z noise in the 2D ion mobility–mass spectrometry (IM-MS) spectrum. For N2, Ar, and CO2, tuning was performed in the chosen drift gas. During gas switching, the DT was allowed to equilibrate for at least 60 min, after which, pressures were confirmed to be stable and minor adjustments made as necessary. The HPF was operated at 4.80 Torr for N2 and Ar, 4.35 Torr for He, and 4.30 Torr for CO2. The TF was operated at 3.80 Torr for N2, 3.74 Torr for Ar, and 3.72 Torr for both CO2 and He. CCS measurements utilize a stepped-field procedure in which several drift fields are surveyed in order to determine the ion transit time within the mobility drift region. For N2, Ar, and CO2, the specific voltages used for the DT and associated ion transfer optics (TF exit, rear ion funnel, and post-IM hexapole) are identical to settings used in a standardized CCS method described in a recent interlaboratory study [33]. Specifically, this standardized, stepped-field method incorporates seven electric field strengths (E/N, where E is electric field and N is the molecular number density) between 8 and 15 Td with a static pressure of 3.95 Torr in the DT. For He, the same DT pressure (3.95 Torr) is utilized; however, a different range of electric fields is surveyed between 6 and 13 Td to optimize resolving power across a broad mass range while mitigating electrical breakdown of the gas. Detailed experimental settings for each drift gas are provided in Table S1 of the supporting information. The trap release time (referred to as ion gating time in other IM instrumentations) was set to 100 μs for all experiments to maximize instrument resolving power [43], and the TF exit voltage (defining the ion “injection” voltage into the DT) was kept at 10 V, minimizing end effects which otherwise shift drift times to lower values [44]. Ion source conditions were as follows: 325 °C gas temperature, 13 L/min drying gas flow rate, 275 °C and 12 L/min sheath gas temperature and flow rate, and nebulizer pressure at 20 psig. Additional experimental conditions for each drift gas are summarized in Table S1. The vendor-supplied software (LC/MS Data Acquisition B.07.00, Agilent) was used for all data acquisition.

A conceptual schematic of the commercial drift tube ion mobility–mass spectrometer (6560, Agilent) used in this work. The selected drift gas is supplied to the high-pressure funnel (HPF), trap funnel (TF), and drift tube (DT) regions. The flow controller adjusts the gas flow into the TF region based on the DT pressure readback, maintaining a constant pressure in the DT. The DT is isolated from the vacuum system, and gas evacuation from DT is thus facilitated via the entrance and exit apertures of the chamber

Variable Pressure Experiments

In prior work with He drift gas, it was found that the operational pressures of the HPF and TF had an effect on the measured CCS, presumably due to changes in gas purity within the DT [34, 45]. In order to better characterize these pressure dependencies, the gas pressures were varied in increments of 0.10 Torr and 0.02 Torr for the HPF and TF regions, respectively, while keeping the DT at 3.95 Torr. This allowed CCS measurements to be obtained at multiple pressure combinations for both regions. The upper pressure limits surveyed for N2, Ar, and CO2 were based upon pressures utilized for normal N2 operation (i.e., 4.80 Torr in the HPF and 3.80 Torr in the TF) [31]. Operational limits of the flow controller (calibrated for N2) restricted helium experiments to a maximum of 4.63 Torr in the HPF with 3.80 Torr in the TF. To obtain CCS values comparable to those reported in the literature, measurements were taken above the minimum operational pressure bounds of the HPF and TF; however, despite the proximity to operational pressure limits, CCS measurements were reproducible.

Effective Length

CCS values measured in all drift gases are listed in Table S2, with CCS values not observed in all drift gases listed in Table S3, and were calculated using a drift tube effective length of 78.06 cm. The effective length differs slightly from the geometric length of the instrument (ca. 78.12 cm), and is determined using a previously reported protocol whereby CCS values for the MS tuning mixture (hexakis(fluoroalkoxy)phosphazenes, HFAP, m/z 322–2722) are scaled to reference measurements obtained using a gridded DT instrument [33, 46]. The effective length determined from this procedure is instrument specific and was used to calculate CCS values for all drift gases.

Chemical Standards

Isopropanol, acetonitrile, water, and formic acid (Optima LC-MS grade) were obtained from Fisher Scientific. The chemical standards were purchased from several vendors, summarized in Table S4. Tetraalkylammonium salts (TAA) were received as dry powder and reconstituted in isopropanol. All chemical standards except the HFAP tuning mixture were prepared at 10 μg/mL and directly infused into the ESI source at a flow rate of 10 μL/min. Poly-DL-alanine and maltose standards were prepared in methanol:water (50:50% v:v) with 0.1% formic acid. The MS tuning mixture containing HFAP (ESI-L Low Concentration Tuning Mixture, Agilent) is supplied from the vendor as a mixture of components dissolved in acetonitrile:water (95:5% v:v), and was prepared as per the vendor instructions by diluting the solution by a factor of 10 using acetonitrile:water (98:2% v:v).

Results and Discussion

Analyte Selection

The analytes chosen for this study were selected as belonging to sets of structurally homogeneous molecules spanning a wide mass coverage (Figure 2a). Specifically, HFAP increases by symmetric additions of fluoroalkyl (CF2) subunits to the six terminal ethers, while TAA cations increase symmetrically by alkyl (CH2) subunits, and the carbohydrates represent oligosaccharides with repeating α-D-glucose units linked by an α(1 → 4) glycosidic bond. Although the MS tuning mixture also contains m/z 118 (betaine), this molecule is not a HFAP, and thus was not included in this study. Poly-DL-alanine has been used in previous IM studies for CCS calibration [47] and, in addition to possessing repeating alanine subunits, forms multiple charge states from ESI, allowing for the investigation of charge state effects in different drift gases.

Pressure Effects

Pressure conditions in the ion transfer funnels prior to the drift tube were systematically investigated for each drift gas to determine the effect on the measured CCS. The cesium cation (Cs+) was used for quantitative comparisons of the CCS measurement due to ease of ionization and lack of multiple conformations, and CCS measurements have been previously documented in the literature for the drift gases investigated in this present study. The Cs+ CCS results for select combinations of pressure conditions are presented in Figure 3, representing the upper (red boxes) and lower (blue boxes) limits of pressures surveyed for each funnel region. In all cases, the drift tube pressure was maintained at 3.95 Torr. The CCS value and corresponding variance reported in the literature for Cs+ are also shown at the bottom of each panel (unfilled bars), as reported for He, N2, Ar, and CO2 [48]. While there was no significant change in the N2 CCS (DTCCSN2) values for Cs+ (0.08% difference or less), CCS measurements in the other drift gases were sensitive to HPF and TF pressure changes, most notably with changes to the TF pressure, where differences as high as 47.96%, 7.99%, and 0.81% in CCS were observed for He, CO2, and Ar, respectively. Previously, it has been suggested that, for this particular instrument configuration, the pressure difference between the TF and the DT affects the gas purity within the IM region [31, 45], and our results support this idea, with smaller pressure differences shifting the Cs+ DTCCSHe to higher values, and to lower CCS values for the other gases, implicating contamination of the drift tube with gas from the ion source, the latter of which is N2 sourced from the boil-off of a cryogenic tank. Though not reported previously, it was found in this study that lower pressures in the upstream HPF could also improve gas purity in the DT, and this effect is shown in Figure 3 for He, Ar, and CO2. As with the TF pressure, lowering the HPF pressure affected the Cs+ CCS measurement by shifting it to lower values for He, and higher values for Ar and CO2. In He, the CCS continues to decrease as the HPF and TF pressures are reduced, with the lowest pressures surveyed exhibiting the closest CCS correlation to the literature. The CCS response to HPF and TF pressures indicates improved drift gas purity at lower HPF and TF pressures for drift gases other than nitrogen. At some pressures, the CCS response is minimal as the pressure is further lowered. Since the interpretation is that lower HPF and TF pressures show increased gas purity, as evidenced by better CCS agreement with literature values, the lowest pressures that could be achieved in He, Ar, and CO2, without signal degradation of the reported analytes, are recommended. This CCS shift exhibits some mass dependence, as seen in comparing the CCS of the HFAP tuning mixture ions across various pressure conditions (cf., Figure S1). Specifically, the lower mass HFAP ions (m/z 322 and m/z 622) experience a greater shift in CCS in response to changes in HPF and TF operational pressures, which we interpret as due to a greater magnitude of the so-called end effect documented for DTIMS, where ions subject to either higher fields or less collisional dampening (i.e., He) at the entrance to the IM region experience deeper penetration into the drift region [44, 49]. This delayed thermalization of ions results in a shorter effective drift length, and thus a shift in the apparent measured CCS to lower values as the TF operational pressure is decreased. Because lower m/z ions spend less time in the drift tube, the contribution of these end effects to their overall drift times is greater. For the lower limits of pressure, operating the TF and HPF regions at pressures below those recommended here was found to significantly degrade ion transmission in He, Ar, and CO2. Additionally for Ar, lower pressures resulted in non-linear behavior in the drift times obtained across multiple drift fields, while in He, gas discharge occurs, which manifests as uncorrelated spectral noise in the lower m/z range. The lower pressure limits for N2 were chosen to overlap with the limits observed for the other drift gases. The high pressure limits for operating the TF and HPF regions for each drift gas were determined based on the recommended values previously established for N2 [31]. Recommended pressure settings for all drift gases evaluated are summarized in Table S1.

A comparison of the CCS values obtained for Cs+ (132.91 Da) in multiple drift gases (filled bars) and at various HPF and TF operational pressures (vertical axis labels, in Torr) along with the CCS and corresponding error (outlined bars) reported by Ellis et al. [48]. Error bars for data obtained in this study correspond to seven repeat measurements. Red or blue shading in the vertical axes labels indicates, respectively, high or low relative pressure conditions for the HPF and TF

Ion Source Temperature Effects

CCS changes were also observed when adjusting the ion source gas temperatures (i.e., nebulizer sheath gas and source entrance drying gas). Specifically, when varying ion source gas temperatures, a change as much as 2.7% in the DTCCSHe was observed, while the DTCCSN2 shifted by a more modest amount, 0.3% or less. This result is interpreted as being due to changes in the gas flow dynamics between the ion source and the DT, which results in gas impurities being introduced into the drift region despite efforts to maintain constant operational pressures in the HPF, TF, and DT regions. Thus, the CCS results presented in this study are obtained under constant ion source temperature conditions which were selected in order to achieve a close correlation of Cs+ CCS values to those described in the literature [48].

Ion Injection Potential

The TF exit voltage establishes the potential bias between the TF and the DT. This potential affects the ion “injection” into the DT and plays a role in ion transmission, resolving power, ion internal energy, and the measured drift time [44, 50, 51]. In order to quantitatively evaluate these effects, the potential difference between the TF exit and DT was varied from 0 to 45 V (35 V in He) using the HFAP tuning mixture ions as a test system. Ion transmission, CCS, and resolving power were measured for each injection voltage (Figures S2–S4). It was found that, in all drift gases, ion injection voltages between 5 and 15 V yielded the highest ion transmissions based on peak area analysis (Figure S2), whereas resolving powers were found to be the highest for 10 and 15 V. In this range, no strong correlation was observed for any particular HFAP ion, suggesting that between 10 and 15 V the mass and mobility-dependent effects were minimal. Importantly, the ion injection voltage was found to shift the measured CCS for all gases surveyed, most dramatically for the low (0 and 5 V) and high (≥ 15 V) potential settings. For example, DTCCSN2 differences relative to 10 V for m/z 1522 were found to be between 2.13% and 1.24%, respectively, for 0 V and 45 V conditions. Overall, low ion introduction voltages (≤ 5 V) yielded high CCS values, whereas the high ion introduction voltages (≥ 15 V) resulted in low CCS values regardless of the identity of the drift gas. These results can be interpreted as a consequence of different ion injection energies: specifically, for low voltages, ions spend more time at the DT entrance prior to being entrained in the drift field, whereas for high voltages, ions penetrate deeper into the drift region before reaching a steady-state drift velocity. It is somewhat surprising that, without an ion introduction potential (0 V), ions still transfer against a pressure gradient into the DT, although this observation was not investigated further in this work. Also of note is that, despite what is typically observed for drift tube instruments, the higher ion injection potentials in this DTIMS configuration did not yield more ion signal, but rather decreased ion transmission (Figure S2). The default setting for the injection potential (designated as the TF exit voltages in the software) is 10 V, which yielded good results in terms of high ion transmission and high resolving power for all gases and HFAP ions evaluated. As such, the TF exit voltage used for all subsequent experiments was 10 V.

CCS Measurements

The CCS measurement reproducibility (precision) was found to depend on the drift gas. For example, 95% of the DTCCSHe values exhibit an RSD of less than 1.4%, whereas in Ar, CO2, and N2, the precision was found to be much better, with the majority (95%) of CCS values exhibiting less than 0.6%, 0.5%, and 0.3% RSD, respectively (c.f., Figure S5). The cause of the lower precision in He is likely due to pressure fluctuations during CCS measurements as a result of the pressure controller valve orifice used in this work being optimized for N2, although it should be noted here that the vendor offers high-flow valve configurations which should improve the pressure control when operating in He drift gas. In order to keep the recommended parameters in this work accessible to a wider network of researchers, an alternate pressure controller optimized for He was not used. Instead, the pressure controller shipped with the alternate gas kit was used for all four drift gases. As noted previously, both the HPF and TF pressures affect the CCS, and operating the instrument at the lower HPF and TF pressures yields measurements which are closely aligned with the canonical CCS values. Note that the CCS value for Cs+ in He never matched with the literature value, even accounting for error. As only a single literature source could be found which reported DTCCSHe values for the cesium cation, this observation could not be further evaluated. While HFAP ion CCS values have not been previously published for gases other than N2, HFAP ions were compared to previously published DTCCSN2 values (Figure S6) [33, 52], demonstrating excellent agreements of 0.56% or less, with a relative standard deviation of measurements taken for this study of 0.31% or less. For poly-DL-alanine, CCS values obtained in this work showed less agreement with the literature, with a maximum bias of 1.7% observed for N2 and a 4.8% bias for He (Figure S7). This agreement is still seen as reasonable, given these measurements were from disparate instrument designs and the error reported for the literature values was estimated at 3% [33, 52]. Previously published He and N2 values for TAA cations [33, 52] were also compared to the current measurements (Figure S8), and it was found that, in general, the literature values were typically higher, with differences ranging from − 2.96 to 3.67% observed among the different reports. Overall, the settings recommended in this study (Table S1) provide good CCS measurement reproducibility while corresponding reasonably well to prior measurements. Ongoing international efforts are aimed at further improvements in CCS measurement precision and accuracy.

Chemical Class Behavior

The gas-specific conformational space plots for all analytes investigated are shown in Figure 4. The low mass region is highlighted in each of the insets and depicts a region of IM-MS space where multiple chemical classes reside in close proximity. In general, all of the class-specific mobility–mass trends are qualitatively the same with the higher charge state ions exhibiting larger CCS values than the lower charge state ions, while for singly charged ions, the CCS increases in the following order: HFAP < carbohydrates < peptides < TAA cations. As discussed in a number of previous reports, this conformational ordering is indicative of the relative gas-phase packing efficiency of each chemical class, with ions exhibiting less restrictive degrees of freedom (peptides and carbohydrates) able to arrange themselves into more compact gas-phase structures [53, 54]. For singly charged ions, the relative CCS values in N2 and Ar are similar, with DTCCSAr values for the same analyte ion being slightly lower than those measured in N2. This observation indicates that drift gas polarizability has a stronger effect on CCS than drift gas mass (vide infra). Note that for multiply charged species, the CCS differences are greater between the various gases than singly charged species. This is apparent in Figure 4 when comparing the relative spacing between the poly-DL-alanine + 2 and + 3 ion trends (dark-blue triangles) and the + 1 trend (light-blue triangles), as well as plotting CCS as a function of gas polarizability (Figure S9), where linear fits to the higher charge states exhibit larger slopes. In addition to charge state effects, the carbohydrates as a whole are strongly affected by the identity of the drift gas compared to the other classes investigated. This effect is shown in Figure 5, where the carbohydrates shift in drift time to a greater extent than other classes, resulting in an inversion in the IM elution orders. For example, in CO2, polyalanine 13-mer (blue dashed trace, m/z 942.50) exhibits a lower measured drift time than the carbohydrate, maltohexaose (orange dashed trace, m/z 1013.32). In all other drift gases, however, this relative elution order is reversed. This effect has been noted previously for small molecules with masses below 500 Da [18, 24], and this present work demonstrates that CCS inversion can occur at higher masses as well. This drift gas selectivity can be useful depending upon the ion species being separated. For instance, in the peak-to-peak resolution (Rpp) example shown in Figure 5, utilizing N2 or Ar would be ideal for the separation of the lower mass ions shown; however, the best resolution for certain ion pairs is observed in CO2 specifically between HFAP m/z 322 and maltose (labeled as analytes A and B). It is interesting to note that, with respect to the relative elution orders and resolutions observed, IM separations in Ar (Ar mass: 39.96 Da, Ar polarizability: 1.64 Å3) are most similar to those observed in N2 (28.01 Da, 1.74 Å3) rather than in CO2 (43.99 Da, 2.91 Å3) [55], indicating that CCS is more dependent on the polarizability of the drift gas than the neutral drift gas mass for the species measured here. While the experimental CCS is a function of both ion and drift gas size, the relative size of the drift gas as experienced by the ion is dominated by its polarizability, and thus plots of CCS vs polarization exhibit near-linear trends [21]. This is shown in Figure 6a, with the select ions investigated plotted as a function of the drift gas polarizability. Of note is that, despite the relative differences in CCS observed across the different drift gases surveyed, ions of similar chemical class exhibit similar slopes in the CCS vs polarizability plot.

Mass vs CCS plots for each drift gas investigated. The locations of all measurements are designated with gray symbols for comparison. The inset in each panel shows an expanded region at low m/z which contains various compound classes. Note that the CCS of carbohydrates (orange squares) relative to the other compounds exhibits a strong dependency on the identity of the drift gas utilized

(a) Relative abundance (R.A.) vs drift time for two ions from each class is shown for the four drift gases at the same field strength. Solid lines show four ions of similar mass, with one ion from each of the four classes (structures are depicted in Figure 2b); dashed lines show four ions of higher mass, with one ion from each class. (b) Two-peak resolution (Rpp) is shown as histogram plots for each closest-mass ion pair of the lower mass group, those depicted with solid lines in the IM spectra. Note the drift time inversion for the high-mass carbohydrate (dashed orange) and polyalanine (dashed blue) in CO2 compared to the other three drift gases

(a) The CCS for select ions plotted against the polarizability of the drift gas as given in the CRC Handbook of Chemistry and Physics [55]. All ions are singly charged except polyalanine 14-mer (PAla 14) which is doubly charged. Increasing the polarizability of the drift gas is correlated with an increase in CCS. However, the relative change in CCS with the drift gas polarizability is both class and charge state specific, as indicated by the different slopes. The slope, intercept, and regression coefficient values are given in Table S5. Error bars are within the marker size. (b) Resolving power (Rp) and peak capacity bar graphs for each drift gas. Maximum Rp values are shown, requiring a different drift field for He (8.3 V/cm) vs the other drift gases (16.0 V/cm). Peak capacity was calculated between HFAP and TAA cations of similar mass. Error bars were based on five measurements conducted on different days

Drift Gas Selection Criteria

In choosing the appropriate drift gas, analytical figures-of-merit such as single-peak resolving power (Rp), two-peak resolution (Rpp), and peak capacity are important considerations. Equations associated with these analytical figures-of-merit can be found in the supporting information. Peak capacity, a measure of the number of peaks that can occupy a given analytical separation space at half height, was found to be the highest in Ar, followed by N2 at the lower mass range (Figure 6b, top panel), whereas N2 outperformed all of the other gases for higher mass analytes due to the ability for N2 to access higher resolving powers in this mass range (Figure 6b, bottom panel). CO2 exhibited the lowest peak capacities for the two mass ranges investigated, but certain systems may benefit from the increased analytical selectivity as previously described. Overall, N2 would be recommended in most cases due to low %RSD, excellent peak capacity, and a consistently high resolving power over a wide mass range. Helium may be chosen when comparison to computational or literature values is needed. Argon performed similarly to nitrogen but may be chosen over nitrogen if a slight increase in resolving power is needed for lower mass analytes. CO2 may be chosen to improve separation for specific analyte pairs.

Conclusion

This work evaluates detailed experimental conditions necessary for operating a commercial drift tube instrument (Agilent 6560) with a variety of drift gases that include He, N2, Ar, and CO2. The criteria used to evaluate the optimal instrument settings needed for each gas include those parameters which provided the highest measurement repeatability of the CCS and the closest correspondence of CCS (e.g., cesium, tuning mixture ions, and poly-DL-alanines) to previously published values. Using these optimal operational settings, a large and highly consistent set of CCS measurements (N = 280, 56 unique ions with 5 replicates each) for a variety of structurally heterogeneous compounds (TAA cations, poly-DL-alanines, fluoroalkyl phosphazenes, and α(1 → 4)-linked glucose oligosaccharides) are subsequently compiled, which are suitable as reference values for future studies. The specific CCS trends observed were found to correlate strongly with the drift gas polarizability, thus providing a basis for predicting relative elution orders for gases not yet investigated. Overall, it was found that N2 exhibited the highest resolving powers and peak capacities across a broad range of masses with a correspondingly high CCS reproducibility (less than 0.40% RSD). CO2 exhibited relatively low peak capacities, but demonstrated high chemical class and charge state-specific selectivity, and, in some cases, resulted in inverted analyte elution orders as compared to the other drift gases. In general, the reference CCS values, the comparison of their response across the various classes, charge states, and masses surveyed in each drift gas, and recommended experimental parameters outlined in this manuscript are expected to aid IM researchers in selecting the drift gas appropriate for their analytical problem, as well as provide guidance for incorporating alternative drift gases in future work. Finally, the highly consistent CCS values measured in this study can be used as a basis for improving fundamental IM theory and developing algorithms which consider the identity of the drift gas in predicting IM elution behavior.

References

May, J.C., Morris, C.B., McLean, J.A.: Ion mobility collision cross section compendium. Anal. Chem. 89, 1032–1044 (2017)

Metz, T.O., Baker, E.S., Schymanski, E.L., Renslow, R.S., Thomas, D.G., Causon, T.J., Webb, I.K., Hann, S., Smith, R.D., Teeguarden, J.G.: Integrating ion mobility spectrometry into mass spectrometry-based exposome measurements: what can it add and how far can it go? Bioanalysis. 9, 81–98 (2017)

Sans, M., Feider, C.L., Eberlin, L.S.: Advances in mass spectrometry imaging coupled to ion mobility spectrometry for enhanced imaging of biological tissues. Curr. Opin. Chem. Biol. 42, 138–146 (2018)

Schrimpe-Rutledge, A.C., Sherrod, S.D., McLean, J.A.: Improving the discovery of secondary metabolite natural products using ion mobility–mass spectrometry. Curr. Opin. Chem. Biol. 42, 160–166 (2018)

Morrison, K.A., Clowers, B.H.: Contemporary glycomic approaches using ion mobility–mass spectrometry. Curr. Opin. Chem. Biol. 42, 119–129 (2018)

May, J.C., Gant-Branum, R.L., McLean, J.A.: Targeting the untargeted in molecular phenomics with structurally-selective ion mobility-mass spectrometry. Curr. Opin. Biotechnol. 39, 192–197 (2016)

May, J.C., McLean, J.A.: Ion mobility-mass spectrometry: time-dispersive instrumentation. Anal. Chem. 87, 1422–1436 (2015)

May, J.C., McLean, J.A.: Advanced multidimensional separations in mass spectrometry: navigating the big data deluge. Annu. Rev. Anal. Chem. 9, 387–409 (2016)

Purves, R.W., Ozog, A.R., Ambrose, S.J., Prasad, S., Belford, M., Dunyach, J.J.: Using gas modifiers to significantly improve sensitivity and selectivity in a cylindrical FAIMS device. J. Am. Soc. Mass Spectrom. 25, 1274–1284 (2014)

Waraksa, E., Perycz, U., Namiesnik, J., Sillanpaa, M., Dymerski, T., Wojtowicz, M., Puton, J.: Dopants and gas modifiers in ion mobility spectrometry. TrAC Trends Anal. Chem. 82, 237–249 (2016)

Schneider, B.B., Covey, T.R., Nazarov, E.G.: DMS-MS separations with different transport gas modifiers. Int. J. Ion Mobil. Spectrom. 16, 207–216 (2013)

Kafle, A., Coy, S.L., Wong, B.M., Fornace, A.J., Glick, J.J., Vouros, P.: Understanding gas phase modifier interactions in rapid analysis by differential mobility-tandem mass spectrometry. J. Am. Soc. Mass Spectrom. 25, 1098–1113 (2014)

Levin, D.S., Vouros, P., Miller, R.A., Nazarov, E.G., Morris, J.C.: Characterization of gas-phase molecular interactions on differential mobility ion behavior utilizing an electrospray ionization-differential mobility-mass spectrometer system. Anal. Chem. 78, 96–106 (2006)

Porta, T., Varesio, E., Hopfgartner, G.: Gas-phase separation of drugs and metabolites using modifier-assisted differential ion mobility spectrometry hyphenated to liquid extraction surface analysis and mass spectrometry. Anal. Chem. 85, 11771–11779 (2013)

Fernández-Maestre, R., Wu, C., Hill Jr., H.H.: Buffer gas modifiers effect resolution in ion mobility spectrometry through selective ion-molecule clustering reactions. Rapid Commun. Mass Spectrom. 26, 2211–2223 (2012)

Butcher, D., Miksovska, J., Ridgeway, M.E., Park, M.A., Fernandez-Lima, F.: The effects of solution additives and gas-phase modifiers on the molecular environment and conformational space of common heme proteins. Rapid Commun. Mass Spectrom. 33, 399-404 (2018)

Garabedian, A., Leng, F., Ridgeway, M.E., Park, M.A., Fernandez-Lima, F.: Tailoring peptide conformational space with organic gas modifiers in TIMS-MS. Int. J. Ion Mobil. Spectrom. 21, 43–48 (2018)

Asbury, G.R., Hill, H.H.: Using different drift gases to change separation factors (alpha) in ion mobility spectrometry. Anal. Chem. 72, 580–584 (2000)

Beegle, L.W., Kanik, I., Matz, L., Hill, H.H.: Electrospray ionization high-resolution ion mobility spectrometry for the detection of organic compounds, 1. Amino acids. Anal. Chem. 73, 3028–3034 (2001)

Beegle, L.W., Kanik, I., Matz, L., Hill, H.H.: Effects of drift-gas polarizability on glycine peptides in ion mobility spectrometry. Int. J. Mass Spectrom. 216, 257–268 (2002)

Matz, L.M., Hill Jr., H.H., Beegle, L.W., Kanik, I.: Investigation of drift gas selectivity in high resolution ion mobility spectrometry with mass spectrometry detection. J. Am. Soc. Mass Spectrom. 13, 300–307 (2002)

Fasciotti, M., Sanvido, G.B., Santos, V.G., Lalli, P.M., McCullagh, M., de Sa, G.F., Daroda, R.J., Peter, M.G., Eberlin, M.N.: Separation of isomeric disaccharides by traveling wave ion mobility mass spectrometry using CO2 as drift gas. J. Mass Spectrom. 47, 1643–1647 (2012)

Fasciotti, M., Lalli, P.M., Klitzke, C.F., Corilo, Y.E., Pudenzi, M.A., Pereira, R.C.L., Bastos, W., Daroda, R.J., Eberlin, M.N.: Petroleomics by traveling wave ion mobility-mass spectrometry using CO2 as a drift gas. Energy Fuel. 27, 7277–7286 (2013)

Lalli, P.M., Corilo, Y.E., Fasciotti, M., Riccio, M.F., de Sa, G.F., Daroda, R.J., Souza, G., McCullagh, M., Bartberger, M.D., Eberlin, M.N., Campuzano, I.D.G.: Baseline resolution of isomers by traveling wave ion mobility mass spectrometry: investigating the effects of polarizable drift gases and ionic charge distribution. J. Mass Spectrom. 48, 989–997 (2013)

Bataglion, G.A., Souza, G.H., Heerdt, G., Morgon, N.H., Dutra, J.D., Freire, R.O., Eberlin, M.N., Tata, A.: Separation of glycosidic catiomers by TWIM-MS using CO2 as a drift gas. J. Mass Spectrom. 50, 336–343 (2015)

Chouinard, C.D., Beekman, C.R., Kemperman, R.H.J., King, H.M., Yost, R.A.: Ion mobility-mass spectrometry separation of steroid structural isomers and epimers. Int. J. Ion Mobil. Spectrom. 20, 31–39 (2017)

Ruotolo, B.T., McLean, J.A., Gillig, K.J., Russell, D.H.: Peak capacity of ion mobility mass spectrometry: the utility of varying drift gas polarizability for the separation of tryptic peptides. J. Mass Spectrom. 39, 361–367 (2004)

Howdle, M.D., Eckers, C., Laures, A.M.F., Creaser, C.S.: The effect of drift gas on the separation of active pharmaceutical ingredients and impurities by ion mobility–mass spectrometry. Int. J. Mass Spectrom. 298, 72–77 (2010)

Jurneczko, E., Kalapothakis, J., Campuzano, I.D.G., Morris, M., Barran, P.E.: Effects of drift gas on collision cross sections of a protein standard in linear drift tube and traveling wave ion mobility mass spectrometry. Anal. Chem. 84, 8524–8531 (2012)

Davidson, K.L., Bush, M.F.: Effects of drift gas selection on the ambient-temperature, ion mobility mass spectrometry analysis of amino acids. Anal. Chem. 89, 2017–2023 (2017)

Kurulugama, R.T., Darland, E., Kuhlmann, F., Stafford, G., Fjeldsted, J.: Evaluation of drift gas selection in complex sample analyses using a high performance drift tube ion mobility-QTOF mass spectrometer. Analyst. 140, 6834–6844 (2015)

Dodds, J.N., May, J.C., McLean, J.A.: Correlating resolving power, resolution, and collision cross section: unifying cross-platform assessment of separation efficiency in ion mobility spectrometry. Anal. Chem. 89, 12176–12184 (2017)

Stow, S.M., Causon, T.J., Zheng, X.Y., Kurulugama, R.T., Mairinger, T., May, J.C., Rennie, E.E., Baker, E.S., Smith, R.D., McLean, J.A., Hann, S., Fjeldsted, J.C.: An interlaboratory evaluation of drift tube ion mobility-mass spectrometry collision cross section measurements. Anal. Chem. 89, 9048–9055 (2017)

May, J.C., Jurneczko, E., Stow, S.M., Kratochvil, I., Kalkhof, S., McLean, J.A.: Conformational landscapes of ubiquitin, cytochrome c, and myoglobin: uniform field ion mobility measurements in helium and nitrogen drift gas. Int. J. Mass Spectrom. 427, 79–90 (2018)

Paglia, G., Williams, J.P., Menikarachchi, L., Thompson, J.W., Tyldesley-Worster, R., Halldórsson, S., Rolfsson, O., Moseley, A., Grant, D., Langridge, J., Palsson, B.O., Astarita, G.: Ion mobility derived collision cross sections to support metabolomics applications. Anal. Chem. 86, 3985–3993 (2014)

Paglia, G., Angel, P., Williams, J.P., Richardson, K., Olivos, H.J., Thompson, J.W., Menikarachchi, L., Lai, S., Walsh, C., Moseley, A., Plumb, R.S., Grant, D.F., Palsson, B.O., Langridge, J., Geromanos, S., Astarita, G.: Ion mobility-derived collision cross section as an additional measure for lipid fingerprinting and identification. Anal. Chem. 87, 1137–1144 (2015)

Regueiro, J., Negreira, N., Berntssen, M.H.G.: Ion-mobility-derived collision cross section as an additional identification point for multiresidue screening of pesticides in fish feed. Anal. Chem. 88, 11169–11177 (2016)

D'Atri, V., Causon, T., Hernandez-Alba, O., Mutabazi, A., Veuthey, J.L., Cianferani, S., Guillarme, D.: Adding a new separation dimension to MS and LC-MS: what is the utility of ion mobility spectrometry? J. Sep. Sci. 41, 20–67 (2018)

Nichols, C.M., Dodds, J.N., Rose, B.S., Picache, J.A., Morris, C.B., Codreanu, S.G., May, J.C., Sherrod, S.D., McLean, J.A.: Untargeted molecular discovery in primary metabolism: collision cross section as a molecular descriptor in ion mobility-mass spectrometry. Anal. Chem. 90, 14484-14492 (2018)

Tao, L., McLean, J.R., McLean, J.A., Russell, D.H.: A collision cross-section database of singly-charged peptide ions. J. Am. Soc. Mass Spectrom. 18, 1232–1238 (2007)

Fernandez-Lima, F.A., Blase, R.C., Russell, D.H.: A study of ion-neutral collision cross-section values for low charge states of peptides, proteins, and peptide/protein complexes. Int. J. Mass Spectrom. 298, 111–118 (2010)

May, J.C., Goodwin, C.R., Lareau, N.M., Leaptrot, K.L., Morris, C.B., Kurulugama, R.T., Mordehai, A., Klein, C., Barry, W., Darland, E., Overney, G., Imatani, K., Stafford, G.C., Fjeldsted, J.C., McLean, J.A.: Conformational ordering of biomolecules in the gas phase: nitrogen collision cross sections measured on a prototype high resolution drift tube ion mobility-mass spectrometer. Anal. Chem. 86, 2107–2116 (2014)

May, J.C., Dodds, J.N., Kurulugama, R.T., Stafford, G.C., Fjeldsted, J.C., McLean, J.A.: Broadscale resolving power performance of a high precision uniform field ion mobility-mass spectrometer. Analyst. 140, 6824–6833 (2015)

Kemper, P.R., Bowers, M.T.: A hybrid double-focusing mass spectrometer - high-pressure drift reaction cell to study thermal energy reactions of mass-selected ions. J. Am. Soc. Mass Spectrom. 1, 197–207 (1990)

May, J.C., McLean, J.A.: A uniform field ion mobility study of melittin and implications of low-field mobility for resolving fine cross-sectional detail in peptide and protein experiments. Proteomics. 15, 2862–2871 (2015)

Picache, J.A., Rose, B.S., Balinski, A., Leaptrot, K.L., Sherrod, S.D., May, J.C., McLean, J.A.: Collision cross section compendium to annotate and predict multi-omic compound identities. Chem. Sci. 10, 983-993 (2019)

Bush, M.F., Campuzano, I., Robinson, C.V.: Ion mobility mass spectrometry of peptide ions: effects of drift gas and calibration strategies. Anal. Chem. 84, 7124-7130 (2012)

Ellis, H.W., McDaniel, E.W., Albritton, D.L., Viehland, L.A., Lin, S.L., Mason, E.A.: Transport properties of gaseous ions over a wide energy range. Part II. At. Data Nucl. Data Tables. 22, 179–217 (1978)

May, J.C., Russell, D.H.: A mass-selective variable-temperature drift tube ion mobility-mass spectrometer for temperature dependent ion mobility studies. J. Am. Soc. Mass Spectrom. 22, 1134–1145 (2011)

Clemmer, D.E., Jarrold, M.F.: Ion mobility measurements and their applications to clusters and biomolecules. J. Mass Spectrom. 32, 577–592 (1997)

Henderson, S.C., Valentine, S.J., Counterman, A.E., Clemmer, D.E.: ESI/ion trap/ion mobility/time-of-flight mass spectrometry for rapid and sensitive analysis of biomolecular mixtures. Anal. Chem. 71, 291–301 (1999)

Hines, K.M., May, J.C., McLean, J.A., Xu, L.: Evaluation of collision cross section calibrants for structural analysis of lipids by traveling wave ion mobility-mass spectrometry. Anal. Chem. 88, 7329–7336 (2016)

Fenn, L.S., McLean, J.A.: Simultaneous glycoproteomics on the basis of structure using ion mobility-mass spectrometry. Mol. BioSyst. 5, 1298–1302 (2009)

McLean, J.A.: The mass-mobility correlation redux: the conformational landscape of anhydrous biomolecules. J. Am. Soc. Mass Spectrom. 20, 1775–1781 (2009)

Rumble, J.R.: CRC Handbook of Chemistry and Physics, 99th edn. CRC Press/Taylor & Francis, Boca Raton, FL (2018)

Acknowledgements

The authors gratefully acknowledge Ruwan Kurulugama and John Fjeldsted at Agilent Technologies and Robin Kemperman and Richard Yost at the University of Florida for insightful discussions regarding the use of alternative drift gases on the instrument platform used in this study. This work was supported in part using the resources of the Center for Innovative Technology at Vanderbilt University. Financial support for this work was provided by the National Institutes of Health (NIH NIGMS R01GM092218 and NCI R03CA222452-01), the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency under Assistance Agreement No. 83573601, and the U.S. Army Research Office and the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA) under Cooperative Agreement No. W911 NF-14-2-0022. This work has not been formally reviewed by EPA. The views expressed in this document are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of the funding agencies and organizations. EPA, DARPA, or the U.S. Government does not endorse any products or commercial services mentioned in this publication.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Electronic Supplementary Material

ESM 1

(DOCX 355 kb)

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Morris, C.B., May, J.C., Leaptrot, K.L. et al. Evaluating Separation Selectivity and Collision Cross Section Measurement Reproducibility in Helium, Nitrogen, Argon, and Carbon Dioxide Drift Gases for Drift Tube Ion Mobility–Mass Spectrometry. J. Am. Soc. Mass Spectrom. 30, 1059–1068 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s13361-019-02151-4

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s13361-019-02151-4