Abstract

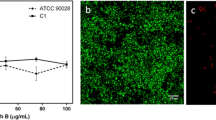

Infections caused by fungal biofilms with rapidly evolving resistance against the available antifungal agents are difficult to manage. These difficulties demand new strategies for effective eradication of biofilms from both biological and inert surfaces. In this study, polymeric micelles comprised of di-block polymer, poly-(ethylene glycol) methyl ether methacrylate and poly 2-(N,N-diethylamino) ethyl methacrylate polymer, P(PEGMA-b-DEAEMA), were observed to exhibit remarkable inhibitory effects on hyphal growth of Candida albicans (C. albicans) and C. tropicalis, thus preventing biofilm formation and removing existing biofilms. P(PEGMA-b-DEAEMA) micelles showed biofilm removal efficacy of > 40% and a 1.4-log reduction in cell viability of C. albicans in its single-species biofilms. In addition, micelles alone promoted high removal percentage in a mixed biofilm of C. albicans and C. tropicalis (~ 70%) and remarkably reduced cell viability of both strains. Co-delivery of fluconazole (Flu) and amphotericin B (AmB) with micelles showed synergistic effects on C. albicans biofilms (3-log reduction for AmB and 2.2-log reduction for Flu). Similar effects were noted on C. albicans planktonic cells when treated with the micellar system combined with AmB but not with Flu. Moreover, micelle-drug combinations showed an enhancement in the antibiofilm activity of Flu and AmB against dual-species biofilms. Furthermore, in vivo studies using Caenorhabditis elegans nematodes revealed no obvious toxicity of the micelles. Targeting morphologic transitions provides a new strategy for defeating fungal biofilms of polymorphic resistance strains and can be potentially used in counteracting Candida virulence.

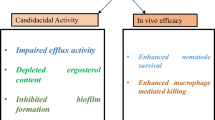

Graphical abstract

Similar content being viewed by others

Data availability

All data are available in the manuscript.

References

Prasad R, Shah AH, Dhamgaye S. Mechanisms of drug resistance in fungi and their significance in biofilms, in Antibiofilm Agents. Springer 2014. p. 45–65.

Tsui C, Kong EF, Jabra-Rizk MA. Pathogenesis of Candida albicans biofilm. FEMS Pathogens and Disease. 2016. 74(4): p. ftw018.

Voltan AR, et al. Fungal diseases: could nanostructured drug delivery systems be a novel paradigm for therapy? Int J Nanomed. 2016;11:3715.

Sudbery PE. Growth of Candida albicans hyphae. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2011;9(10):737–48.

Lohse MB, et al. Development and regulation of single-and multi-species Candida albicans biofilms. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2018;16(1):19.

Tan Y, et al. Efficacy of carboxymethyl chitosan against Candida tropicalis and Staphylococcus epidermidis monomicrobial and polymicrobial biofilms. Int J Biol Macromol. 2018;110:150–6.

Weerasekera MM, et al. Culture media profoundly affect Candida albicans and Candida tropicalis growth, adhesion and biofilm development. Memórias Do Instituto Oswaldo Cruz. 2016;111(11):697–702.

Jiang C, et al. Significance of hyphae formation in virulence of Candida tropicalis and transcriptomic analysis of hyphal cells. Microbiol Res. 2016;192:65–72.

Ramage G, Robertson SN, Williams C. Strength in numbers: antifungal strategies against fungal biofilms. Int J Antimicrob Agents. 2014;43(2):114–20.

Rodríguez-Cerdeira C, et al. Biofilms and vulvovaginal candidiasis. Colloids and Surfaces B: Biointerfaces; 2018.

Sawant B, Khan T. Recent advances in delivery of antifungal agents for therapeutic management of candidiasis. Biomed Pharmacother. 2017;96:1478–90.

Tobudic S, et al. Antifungal susceptibility of Candida albicans in biofilms. Mycoses. 2012;55(3):199–204.

Cavalheiro M, Teixeira MC. Candida biofilms: threats, challenges, and promising strategies. Front Med. 2018;5:28.

Fanning S, Mitchell AP. Fungal biofilms. PLoS Pathog. 2012. 8(4).

Pathirana RU, et al. Filamentous non-albicans Candida species adhere to Candida albicans and benefit from dual biofilm growth. Frontiers in microbiology. 2019;10:1188.

Carmello JC, et al. Photoinactivation of single and mixed biofilms of Candida albicans and non-albicans Candida species using Photodithazine®. Photodiagn Photodyn Ther. 2017;17:194–9.

Ramage G, et al. In vitro pharmacodynamic properties of three antifungal agents against preformed Candida albicans biofilms determined by time-kill studies. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2002;46(11):3634–6.

Mayer FL, Wilson D, Hube B. Candida albicans pathogenicity mechanisms. Virulence. 2013;4(2):119–28.

Gauwerky K, Borelli C, Korting HC. Targeting virulence: a new paradigm for antifungals. Drug Discovery Today. 2009;14(3–4):214–22.

Cui J, et al. Synergistic combinations of antifungals and anti-virulence agents to fight against Candida albicans. Virulence. 2015;6(4):362–71.

Nett JE. Future directions for anti-biofilm therapeutics targeting Candida. Expert review of anti-infective therapy. 2014;12(3):375–82.

Li J, et al. Block copolymer nanoparticles remove biofilms of drug-resistant Gram-positive bacteria by nanoscale bacterial debridement. Nano Lett. 2018;18(7):4180–7.

Albayaty YN, et al. pH-Responsive copolymer micelles to enhance itraconazole efficacy against Candida albicans biofilms. J Mater Chem B. 2020;8(8):1672–81.

Ahmed N, et al. Polymeric drug delivery systems for encapsulating hydrophobic drugs. Drug Delivery Strategies for Poorly Water-Soluble Drugs. 2013. p. 151.

Takahashi C, et al. Antibacterial activities of polymeric poly (dl-lactide-co-glycolide) nanoparticles and Soluplus® micelles against Staphylococcus epidermidis biofilm and their characterization. RSC Adv. 2015;5(88):71709–17.

Pierce CG, et al. A simple and reproducible 96-well plate-based method for the formation of fungal biofilms and its application to antifungal susceptibility testing. Nat Protoc. 2008;3(9):1494.

Lu M, et al. Gentamicin synergises with azoles against drug-resistant Candida albicans. Int J Antimicrob Agents. 2018;51(1):107–14.

Seneviratne C, et al. Cell density and cell aging as factors modulating antifungal resistance of Candida albicans biofilms. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2008;52(9):3259–66.

Haque F, et al. Inhibitory effect of sophorolipid on Candida albicans biofilm formation and hyphal growth. Sci Rep. 2016;6:23575.

Manoharan RK, et al. Alizarin and chrysazin inhibit biofilm and hyphal formation by Candida albicans. Front Cell Infect Microbiol. 2017;7:447.

Brilhante RSN, et al. Candida tropicalis from veterinary and human sources shows similar in vitro hemolytic activity, antifungal biofilm susceptibility and pathogenesis against Caenorhabditis elegans. Vet Microbiol. 2016;192:213–9.

Liu H, Kohler J, Fink GR. Suppression of hyphal formation in Candida albicans by mutation of a STE12 homolog. Science. 1994;266(5191):1723–6.

Richter K, et al. Taking the silver bullet colloidal silver particles for the topical treatment of biofilm-related infections. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces. 2017;9(26):21631–8.

Tampakakis E, Okoli I, Mylonakis EAC. elegans-based, whole animal, in vivo screen for the identification of antifungal compounds. Nat Protoc. 2008;3(12):1925.

Thangamani S, Younis W, Seleem MN. Repurposing celecoxib as a topical antimicrobial agent. Frontiers in microbiology. 2015;6:750.

Bandara H, Matsubara VH, Samaranayake LP. Future therapies targeted towards eliminating Candida biofilms and associated infections. Expert review of anti-infective therapy. 2017;15(3):299–318.

Albayaty YN, et al. Enzyme responsive copolymer micelles enhance the anti-biofilm efficacy of the antiseptic chlorhexidine. Int J Pharm. 2019.

Liu Y, et al. Surface-adaptive, antimicrobially loaded, micellar nanocarriers with enhanced penetration and killing efficiency in staphylococcal biofilms. ACS Nano. 2016;10(4):4779–89.

Miyake Y, et al. Antifungal drugs effect adherence of Candida albicans to acrylic surfaces by changing the zeta-potential of fungal cells. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1990;69(3):211–4.

Martinez LR, et al. Demonstration of antibiofilm and antifungal efficacy of chitosan against candidal biofilms, using an in vivo central venous catheter model. J Infect Dis. 2010;201(9):1436–40.

Savard T, et al. Antimicrobial action of hydrolyzed chitosan against spoilage yeasts and lactic acid bacteria of fermented vegetables. J Food Prot. 2002;65(5):828–33.

Shahalom S, et al. Poly (DEAEMa-co-PEGMa): a new pH-responsive comb copolymer stabilizer for emulsions and dispersions. 2006;22(20):8311–8317.

Pierce CG, Saville SP, Lopez-Ribot JL. High-content phenotypic screenings to identify inhibitors of Candida albicans biofilm formation and filamentation. Pathogens and Disease. 2014;70(3):423–31.

Rodrigues ME, et al. Novel strategies to fight Candida species infection. Crit Rev Microbiol. 2016;42(4):594–606.

Tome M, et al. Synergistic and antagonistic effects of immunomodulatory drugs on the action of antifungals against Candida glabrata and Saccharomyces cerevisiae. PeerJ. 2018;6:e4999.

Rodrigues CF, Henriques M. Liposomal and deoxycholate amphotericin B formulations: effectiveness against biofilm infections of Candida spp. Pathogens. 2017;6(4):62.

Torrado J, et al. Amphotericin B formulations and drug targeting. 2008;97(7):2405–25.

Buehler DC, Marsden MD, Shen S. 8, Bioengineered vaults: self-assembling protein shell-lipophilic core nanoparticles for drug. 2014.

Vandermeulen G, et al. Encapsulation of amphotericin B in poly (ethylene glycol)-block-poly (ɛ-caprolactone-co-trimethylenecarbonate) polymeric micelles. 2006;309(1–2):234–240.

Muţ A, et al. Chitosan/HPMC-based hydrogels containing essential oils for topical delivery of fluconazole: Preliminary studies. 2018;66(2):248–56.

Corrêa JCR, Salgado HRN. Review of fluconazole properties and analytical methods for its determination. 2011;41(2):124–132.

Castelli MV, et al. Novel antifungal agents: a patent review (2011–present). 2014;24(3):323–338.

Bachmann SP, et al. Antifungal combinations against Candida albicans biofilms in vitro. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2003;47(11):3657–9.

You J, et al. Small-molecule suppressors of Candida albicans biofilm formation synergistically enhance the antifungal activity of amphotericin B against clinical Candida isolates. ACS Chem Biol. 2013;8(4):840–8.

Kawai A, Yamagishi Y, Mikamo H. In vitro efficacy of liposomal amphotericin B, micafungin and fluconazole against non-albicans Candida species biofilms. J Infect Chemother. 2015;21(9):647–53.

Ann Chai LY, Denning DW, Warn P. Candida tropicalis in human disease. Crit Rev Microbiol. 2010;36(4):282–98.

Yang YQ, et al. pH-sensitive micelles self-assembled from multi-arm star triblock co-polymers poly (ε-caprolactone)-b-poly (2-(diethylamino) ethyl methacrylate)-b-poly (poly (ethylene glycol) methyl ether methacrylate) for controlled anticancer drug delivery. Acta Biomater. 2013;9(8):7679–90.

Lin W, et al. pH-responsive micelles based on (PCL) 2 (PDEA-b-PPEGMA) 2 miktoarm polymer: controlled synthesis, characterization, and application as anticancer drug carrier. Nanoscale Res Lett. 2014;9(1):243.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Dr. Anton Blencowe’s laboratory for providing the (PEG-b-PCL) polymer.

Funding

The Australian Research Council Centre for Excellent in Convergent Bio-Nano Science and Technology (CBNS) has supported this project.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

YNA designed the study, conducted the experiments, and collected and analysed the data. YNA and NT wrote the manuscript. CAP and NT designed the research and reviewed the manuscript. PDR, TPD, JFQ, and MRW synthesized the polymer P(PEGMA-b-DEAEMA) and reviewed the manuscript. All authors have approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Consent for publication

All authors have consented to the publication.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Albayaty, Y.N., Thomas, N., Ramírez-García, P.D. et al. Polymeric micelles with anti-virulence activity against Candida albicans in a single- and dual-species biofilm. Drug Deliv. and Transl. Res. 11, 1586–1597 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s13346-021-00943-4

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s13346-021-00943-4