Abstract

Introduction

The objective of this study was to evaluate real-world treatment patterns of type 2 diabetes (T2D) patients initiating glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonists (GLP-1 RAs) in Germany (GE), the United Kingdom (UK), France (FR), the Netherlands (NE), Belgium (BE), and Sweden (SE).

Methods

Adult T2D patients initiating exenatide twice daily (exBID), liraglutide once daily (LIRA) or exenatide once weekly (exQW) were identified using the IMS LifeLink™ (IMS Health, Danbury, CT, USA): Electronic Medical Records (EMR; GE/UK/FR) and IMS LifeLink™: longitudinal prescriptions (LRx; NE/BE/GE/UK) databases, and national health register data (SE), between 2010 and 2012. Therapy initiation date was termed ‘index date’. Eligible patients had ≥180-day pre- and variable follow-up (minimum ≥360-day post-index exBID and LIRA, ≥180-day post-index exQW). Treatment modification and persistence were evaluated over 180 days. Kaplan–Meier (KM) survival curves and Cox proportional hazards models (PHMs; EMR databases only) evaluated stopping of the index therapy (measured as first of discontinuation or switch).

Results

30,206 exBID, 5,401 exQW, and 52,155 LIRA patients were included in the analysis (46.0–66.9% male; mean age range 55.4–59.3 years). Mean follow-up was 20.3–27.4 months for exBID and LIRA, and 7.6–13.9 months for exQW. Across the databases, the proportion experiencing a treatment modification at 180 days was highest among exBID (37.6–81.7%) compared to LIRA (36.8–56.6%) and exQW (32.3–47.7%). The proportion persistent at 180 days was lowest among exBID patients (46.8–73.5%) compared to LIRA (50.6–80.1%) or exQW (57.5–74.6%). In the KM analyses, LIRA patients had a lower proportion stopping therapy at all time points compared to exBID patients, across the databases. In the Cox PHMs, LIRA was associated with a significantly lower risk of stopping compared to exBID; in GE, exQW was associated with a lower risk compared to exBID and LIRA.

Conclusion

Treatment patterns varied among GLP-1 RA patients, with persistence highest among either LIRA or exQW across countries, and lowest among exBID. Longer-term data would be useful, particularly given limited exQW follow-up due to more recent launch.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The International Diabetes Federation estimates that there are 56.3 million adults with diabetes, representing 8.5% of European adults [1]. Type 2 diabetes (T2D) constitutes 85–95% of all diabetes, and the incidence/prevalence continues to increase due in part to obesity, physical inactivity, and poor diet. This has substantial cost implications to healthcare systems and society [1]. Upon diagnosis of T2D, patients are often required to engage in healthy eating, weight control, and increased physical activity to improve glycemic sensitivity/control [2]. However, most patients will require drug therapy, with metformin monotherapy generally preferred as initial pharmacological treatment. Over time, combination therapy is needed, with the American Diabetes Association (ADA)/European Association for the Study of Diabetes (EASD) recommending one of five treatment classes combined with metformin: a sulfonylurea, thiazolidinediones (TZD), dipeptidyl peptidase-4 (DPP-4) inhibitor, basal insulin or a glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonist (GLP-1 RA) [2].

GLP-1 RAs mimic endogenous GLP-1, stimulating insulin release from the pancreas and suppressing glucagon secretion [2]. GLP-1 RAs are associated with high glycemic efficacy, weight loss and low risk of hypoglycemia, but with some risk of gastrointestinal side effects. While concerns of an association with pancreatic disease exist, the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) and European Medicines Agency (EMA) have agreed that a causal association is inconsistent with the current data [3]. There are five EMA approved GLP-1 RAs: exenatide twice daily (exBID; Byetta®, AstraZeneca; approved in 2006), liraglutide once daily (LIRA; QD; Victoza®, Novo Nordisk; approved in 2009), exenatide once weekly (exQW; Bydureon®, AstraZeneca; approved in 2011), lixisenatide once daily (Lyxumia®, Sanofi; approved in 2013), and albiglutide once weekly (Eperzan™, GlaxoSmithKline; approved in 2014). In addition, the Committee for Medicinal Products for Human Use (CHMP) has recently adopted a positive opinion and recommended the granting of a marketing authorization for dulaglutide once weekly (Trulicity™, Eli Lilly).

Daily doses, injection frequencies and injection time related to meals of current GLP-1 RA therapies are variable. For example, the initial dose of exBID is 5 µg injected under the skin (subcutaneously) twice daily, 60 min before two major meals with at least 6 h in between. The dose can be increased to 10 µg twice daily after 1 month of therapy [4]. LIRA is administered once daily independent of meals and should be initiated with a dose of 0.6 mg once daily for the first week, followed by a dose increase to 1.2 mg once daily [5]. If the 1.2 mg dose does not result in acceptable glycemic control, the dose may be increased to 1.8 mg after at least 1 week, although the EMA [6] and the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) [7] state that the available evidence suggests only marginal benefit of this escalation on glycemic control. ExQW is administered once per week independent of meals at a dose of 2.0 mg [8]. While the ADA/EASD recommend GLP-1 RA therapy in second- or third-line therapy [2], some European Union (EU) health care authorities, including the United Kingdom (UK) [7], the Netherlands (NE) [9], Sweden (SE) [10], and Belgium (BE) [11], generally recommend GLP-1 RAs as a third-line therapy, often restricted to certain populations (obese, intolerant to other therapies, etc.).

Only a few studies have compared treatment patterns or variable dosing between exBID and LIRA [12–14]. Little is known about treatment patterns among GLP-1 RA therapy users in the real-world setting, particularly for exQW, or average patient dosing given variability in dosing for exBID and LIRA. The primary objective of this analysis was to evaluate treatment patterns among T2D GLP-1 RA therapy initiators, specifically persistence with the index therapy and treatment modification [discontinuation, switch, stop (a composite outcome of either discontinuation or switch) or augmentation]. Secondary objectives included evaluating average daily dose (ADD) of the therapy and the patient characteristics associated with risk of stopping therapy. These outcomes were evaluated using available databases containing prescription data in Germany (GE), the UK, France (FR), NE, BE, and SE. When this study was conducted, exBID, exQW, and LIRA were the only approved GLP-1 RAs; therefore, these therapies comprise the cohorts of this study.

Methods

A retrospective cohort analysis was conducted using eight databases in six European countries (GE, the UK, FR, NE, BE, and SE). This study involved a retrospective cohort analysis using eight databases, and the analysis does not contain studies with human or animal subjects performed by any of the authors. Research ethics approval was received from the regional Ethics Review Board in Stockholm in order to conduct the Swedish analysis. Ethics approval was not required in the other countries.

Data Sources

Electronic Medical Records

The IMS LifeLink™ (IMS Health, Danbury, CT, USA): Electronic Medical Records databases (henceforth referred to as EMR) were used in GE, the UK, and FR. EMR contains longitudinal anonymized patient-level data from the EMRs of office-based physician practices [general practitioners (GPs) in the UK/FR, GPs/diabetologists in GE]. Data include basic demographics, physician-recorded medical diagnoses [International Statistical Classification of Diseases (ICD) ICD-10 format] and written prescriptions [EphMRA Anatomical Classification (ATC) code]. EMR covers approximately 18.9%, 6.7%, and 7.6% of the GE, UK, and FR populations, respectively.

Retail Pharmacy

The IMS LifeLink™: Longitudinal Prescriptions databases (henceforth referred to as LRx) were used in the NE, BE, the UK (GPs only; limited to aggregated data analysis due to privacy legislation), and GE. LRx contains prescription data (EphMRA ATC code) and limited demographic data [e.g., age (unavailable in BE; age bands only in the UK), gender]. The representativeness of the databases based upon current population and pharmacy coverage in 2013 is: 72% NE, 32% BE, 51% GE, and 44% UK.

Both EMR and LRx databases were utilized in GE and UK as they provide somewhat different samples: physician-recorded pharmacy and clinical data vs. filled pharmacy prescription data. Overlap in the populations from the two databases is possible.

Sweden

The Swedish national drug register was utilized, which provides national, patient-level data on all prescription drugs dispensed at all pharmacies from the Swedish National Pharmacy Corporation (World Health Organization [WHO] ATC code). In addition, the Swedish Mortality Register was used to identify patient death and provide full visibility into patient follow-up. Research ethics approval was received from the regional Ethics Review Board in Stockholm.

Patient Selection

Patients were first identified based on a prescription for the therapy of interest (exBID, exQW, or LIRA) within the selection window (Table 1), which varied by country and was adjusted for exQW given its more recent launch (June 2011). The first prescription for a therapy of interest within the selection window was termed the ‘index therapy’ and the date was termed the ‘index date’. Patients were followed through the end of continuous eligibility (CE; i.e., visibility) or study end date, whichever occurred first.

Adult patients (≥18 years on the index date) were identified as eligible if they met the following inclusion/exclusion criteria: (1) evidence of T2D [no evidence of type 1 diabetes (T1D); see Table 1 for database-specific criteria], (2) ≥180-day CE pre-index, (3) ≥360-day CE post-index (≥180-day post-index for exQW patients only) within the database (see Table 1 for database-specific CE criteria), (4) naïve to the initiated therapy class with no prescription for any GLP-1 RA (EphMRA ATC A10S0; WHO ATC A10BX04/A10BX07) in the 180-day pre-index period, (5) not initiating any other injectable antihyperglycemic therapy (GLP-1 RA or insulin) on the index date other than the index therapy; and (6) non-missing age or gender required (age unavailable in BE LRx).

Measures and Analysis

Baseline demographic (age and gender where available) characteristics were assessed as well as non-index antihyperglycemic therapy classes used in the pre-index period and concomitant use on the index date. A non-index antihyperglycemic therapy class was defined as concomitant if the time between a prescription for a therapy class in the pre- and post-index was ≤120 days, with overlap on the index date, or if the therapy class was prescribed/filled on the index date. Additional EMR clinical characteristics were summarized where available, including body mass index (BMI), comorbidities in the pre-index and physician type (GP/diabetologist in GE). Patients with missing prescription quantity data were excluded from the subsequent ADD and treatment modification analyses in FR EMR (35.8% exBID, 52.6% LIRA) and NE LRx (0.6% exBID; 3.7% exQW, 0.5% LIRA). There was no missing prescription quantity data for the other databases.

Experience of a first treatment modification was assessed during the 180-day post-index period. Treatment modifications included discontinuation, switch, augmentation, off-label up-titration and down-titration, assessed following previously published methods [13]. Titration was calculated using ADD given the lack of a reliable prescribed dose field. Discontinuation was defined as a gap in a series of successive index therapy prescriptions ≥2× the expected duration of the first prescription. Switching was defined as a new non-index antihyperglycemic prescription (new antihyperglycemic therapy class not observed in the pre-index or index date, or non-index antihyperglycemic therapy from the same class) within 30 days before or after discontinuation of the patient’s index treatment. Augmentation was defined as ≥2 prescriptions for a new non-index antihyperglycemic prescription, started more than 30 days before the end of follow-up or the index discontinuation date. Off-label up-titration was identified as any dose increase outside of label recommendations (daily dose >20 µg for exBID; two consecutive prescriptions with daily dose >1.8 mg for LIRA). Down-titration was defined as two consecutive prescriptions with doses lower than the index dose. Persistence (i.e., continuation of the index therapy) was evaluated during the 180-day post-index period. Patients were considered persistent until evidence of discontinuation or switch. A stop outcome was defined as the occurrence of either discontinuation or switch (whichever came first).

Index therapy ADD was assessed for all patients while persistent (until discontinuation or switch); patients who augmented their index therapy continued to factor into that index therapy’s ADD. ADD was calculated by dividing the total amount or units of drug prescribed by the number of days between two consecutive prescriptions. ADD was evaluated by calendar month intervals for patients with an index therapy prescription within that month. Average ADDs over calendar months were summarized to provide both a yearly and overall ADD. An average weekly dose (AWD) was calculated for exQW by multiplying the ADD by 7. Prescriptions received within 14 days of a previous prescription were excluded to avoid overestimating ADD due to duplicate prescriptions or ambiguous up-titration with an exception for the prescription following the index therapy (i.e., the second prescription) if the gap between the second and third prescription was equal to the expected duration of the prescribed therapy. ADD in the UK LRx (aggregated data) was calculated as follows: total units of drug prescribed in a month were summed and divided by the total number of patients with a prescription in that month; then divided by the number of days in that month. This does not account for multiple prescriptions prescribed for a patient in a month which could result in over-inflation of ADD estimates. For yearly and overall ADD/AWD calculations, calendar months with less than 30 patients were trimmed.

A wide range of ADDs were expected, due to variability in gaps between consecutive prescriptions [13]. Given overall ADD sensitivity to small gaps/overlaps in available prescriptions, we grouped ranges of ADD values in categories consistent with labeled use and dispensed doses to calculate titration outcomes. For exBID: calculated ADD 5–15 µg = 10 µg; calculated ADD >15–25 µg = 20 µg; and calculated ADD >25 µg = dose above label; for LIRA: calculated ADD 0.6–1.5 mg = 1.2 mg; calculated ADD >1.5–2.1 mg = 1.8 mg; and calculated ADD >2.1 mg = dose above label. On-label up-titration was assessed as a separate outcome, defined as any dose increase based on label recommendations (two consecutive prescriptions with ADD of 20 µg for exBID; two consecutive prescriptions with ADD ≥1.2 mg up to 1.8 mg for LIRA).

Descriptive summary statistics were used to describe frequency and percentage distributions for categorical variables while continuous variables were described using the mean/standard deviation/median. Time to stop of the index therapy over the variable follow-up was assessed using Kaplan–Meier (KM) analysis. For the EMR cohorts, Cox proportional hazards models (PHMs) were developed to assess risk of stopping the index therapy. Statistical and descriptive analyses were performed using SAS version 9.1 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA). A P value <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Patient Sample

After application of the inclusion/exclusion criteria, the final sample consisted of 30,206 exBID patients (300 GE EMR/388 UK EMR/120 FR EMR/171 NE LRx/845 BE LRx/23,809 UK LRx/4,230 GE LRx/343 SE), 5,401 exQW patients (174 GE EMR/270 NE LRx/3,207 UK LRx/1,629 GE LRx/121 SE), and 52,155 LIRA patients (906 GE EMR/306 UK EMR/399 FR EMR/2,189 NE LRx/1,384 BE LRx/30,436 UK LRx/12,727 GE LRx/3,808 SE). Because individual patient prescription data were unavailable from the UK LRx due to privacy legislation, it was not possible to evaluate clinical characteristics or treatment patterns; the aggregate UK LRx data allowed only for the aggregate analysis of ADD outcomes.

Demographic and clinical characteristics of the study sample can be found in Table 2. Mean age at index ranged from 55.4 to 59.3 years old for patients across index therapy cohort and database, and approximately half or more were male (46.0–66.9%). ExBID and LIRA patients had approximately 2 years of follow-up; exQW patients had shorter follow-up ranging from 7.6 to 13.9 months. Available demographic characteristics for the UK LRx sample were limited (due to privacy legislation) to age at index prescription [most often between 50 and 64 years (48.2–49.0%)] and gender with over half male (52.7–55.4%) across therapy cohorts.

On average, patients had 1.6–2.3 antihyperglycemic therapy classes in the 180-day pre-index (with a median of 2 classes for most index therapy cohorts), and patients most often used a median of 1 concomitant antihyperglycemic therapy class during index. Biguanides, followed by sulfonylureas were the most common antihyperglycemic therapy classes used in both the 180-day pre-index and concomitant with the index therapy, while insulin use was less frequent.

For EMR, data on BMI were available for most patients only in the UK, where the majority of exBID and LIRA patients had a BMI indicative of obesity (BMI ≥ 30.0) at index (76.8% and 67.0%), although only 12.1% and 10.5% were diagnosed with obesity, respectively. Cardiovascular (CV) disease was the most common comorbidity of interest observed in the 180-day pre-index (range 53.7–63.7%) in GE and UK across cohorts (diagnoses were less frequently recorded in FR).

Treatment Patterns

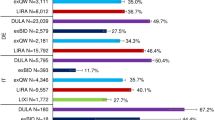

Across databases, the proportion of patients persistent at 180 days was higher among LIRA and exQW patients compared to exBID (Table 3), and for LIRA patients ranged from 50.6% to 80.1% (GE EMR and GE LRx), for exBID patients ranged from 46.8% to 73.5% (FR EMR and NE LRx), and for exQW patients ranged from 57.5% to 74.6% (GE LRx and NE LRx). The proportion persistent at 180 days was highest for exQW in GE EMR, and second to LIRA in NE LRx, GE LRx and SE.

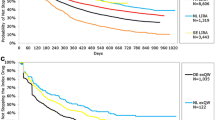

KM results for time to stop (discontinuation or switch) over the variable follow-up by index therapy cohort (excluding the UK LRx) can be found in Fig. 1a–c. Median time to stop for exBID ranged from 95 days to 275 days (GE EMR and NE LRx); 265 days to 377 days for exQW (GE LRx and GE EMR; note: fewer than 50% experienced stop in NE LRx or SE), and 179 days to 814 days for LIRA (GE EMR and GE LRx). Across databases, the proportion stopping was lower among LIRA patients compared to exBID at all time points. Comparisons to exQW are limited given the shorter follow-up period (180 days minimum).

Kaplan–Meier analyses for time to stop: a exBID, b exQW, c LIRA. Patient-level analysis was not possible with the UK LRx due to privacy legislation; therefore, treatment pattern outcomes were not assessed. BE Belgium, EMR Electronic Medical Records databases, exBID exenatide twice daily, exQW exenatide once weekly, FR France, GE Germany, LIRA liraglutide once daily, LRx Longitudinal Prescriptions databases, NE The Netherlands, SE Sweden, UK United Kingdom

Treatment modifications at 180-day post-index can be found in Table 3 by index therapy cohort. More exBID patients experienced treatment modification at 180 days compared to LIRA or exQW patients in each database. More than half of exBID patients experienced treatment modification [ranging from 55.7% to 81.7% (BE LRx and UK EMR)] with the exception of NE LRx (37.6%). Approximately, half of LIRA patients experienced treatment modification ranging from 46.3% to 56.6% (SE and FR EMR), again with the exception of NE LRx (36.8%). The proportion experiencing treatment modification at 180 days among exQW ranged from 32.3% to 47.7% (NE LRx and GE LRx); fewer exQW patients experienced treatment modification compared to LIRA patients in GE EMR (40.8% and 56.2%) and SE (39.7% and 46.3%), while proportions were more similar in NE and GE LRx. Discontinuation was the most common first treatment modification type across index therapies for all countries with the exception of LIRA patients in GE LRx where down-titration was most common.

Cox Proportional Hazards Models for Risk of Stopping

Type of index therapy was significantly associated with risk of stopping in all EMR countries, with LIRA associated with a lower risk of stopping compared to exBID (Table 4). In GE, compared to exBID, exQW was associated with a 54% lower risk while LIRA was associated with a 31% lower risk (both P < 0.001). In UK, compared to exBID, LIRA was associated with a 28% lower risk (P < 0.001). In FR, compared to exBID, LIRA was associated with a 38% lower risk (P = 0.002). In both GE and UK, concomitant use of a biguanide was associated with a lower risk of stopping the index therapy compared to no biguanide use. In GE, other significant predictors for stop included male gender, GP physician type, depression and non-neuropathic pain in the pre-index and no CV disease and concomitant insulin use. It is important to note the availability of physician type in GE only and the different sample sizes, which may impact model findings.

Average Daily Dose

ADD by calendar year (year of prescription) and overall (over the entire follow-up period) is reported in Table 5. Mean (SD) overall ADD for exBID was on the higher end of the approved doses and ranged from 16.39 (1.68) to 19.36 (1.04) µg (SE and UK EMR); overall ADD calculated at the aggregate level in UK LRx was higher: 20.73 (0.58) µg. Overall ADD for LIRA was generally in the middle of the indicated doses and ranged from 1.30 (0.07) to 1.61 (0.15) mg (BE LRx and NE LRx); overall ADD calculated at the aggregate level in UK LRx was 1.49 (0.04) mg. Overall AWD (ADD × 7) exQW ranged from 2.00 (0.07) to 2.14 (0.18) mg (GE LRx and GE EMR); overall AWD calculated at the aggregate level in UK LRx was 2.18 (0.07) mg.

Discussion

Our research suggests that treatment patterns varied among GLP-1 RA patients. Across the databases, the proportion of patients that experienced a treatment modification and that stopped the index therapy by 180-day post-index were higher among exBID compared to LIRA QD or exQW patients. A greater proportion of exBID patients stopped therapy than LIRA patients at all time points in the KM analyses, further supported by the Cox PHMs. While treatment pattern results for ExQW varied by dataset relative to LIRA, the Cox PHM results in GE EMR supported the observed lower likelihood of stopping for exQW relative to LIRA and exBID. The exQW data should be interpreted with caution; comparisons are restricted given the shorter follow-up due to more recent launch. While the overall ADDs of GLP-1 RAs were generally within the indicated ranges, the overall ADD for LIRA was generally in the middle of the indicated doses (1.2 or 1.8 mg following the second week); and on average, higher than the 1.2 mg dosing recommended by the EMA [6] and NICE [7], suggesting that on average, many patients are using and benefitting from the higher dose. Some differences between treatment patterns by index therapy were observed between databases in GE (EMR and LRx), including the proportion stopping therapy; it is important to consider the different populations (physician EMR records vs. filled pharmacy claims) and variable follow-up periods, as well as the much higher sample size for LRx. Overall ADD results in GE EMR compared to GE LRx were similar (exBID: 17.65, 17.70 µg; exQW: 0.31, 0.29 mg; LIRA: 1.44, 1.40 mg, respectively). The ADD was higher as calculated in the UK LRx for all therapies compared to the UK EMR, likely related to over-estimation with the aggregate-level analysis. It is important to note that the prescription of GLP-1 RA therapies in the countries evaluated may be influenced by local regulation and reimbursement policies, such as reimbursement in the third-line setting only among restricted populations [7, 9–11], prescribing restricted to specialists [15] or even restrictive prescribing targets for physicians [16], related to the costs and cost-effectiveness perceptions of GLP-1 RA therapies which may vary in each considered country.

The results presented must be viewed in light of some limitations associated with using electronic medical record and prescription data. Patients included in EMR (and their physicians) and LRx databases may not be fully representative of all patients in the respective country, as data are collected only from physicians who have agreed to participate in the EMR panel or only from pharmacies which participate in the database. For EMR, only care within the EMR practice setting is visible, and data linkage is not available if a patient visits multiple physicians within the EMR panel, as the patient is assigned different identification numbers by each physician. The prescription information only highlights prescriptions written by the participating physician, with no information on actual pharmacy fills. As mentioned earlier, the UK and FR data are limited to GPs. LRx lacks visibility to any prescriptions purchased outside the pharmacies included in the database. The lack of medical diagnosis codes in LRx and SE made it difficult to confirm the presence/absence of T1D and/or T2D, however, oral antihyperglycemic medication (OAM) use in the 180-day pre-index was required, with the exception of the UK LRx where no patient-level data are available. It is possible that the UK LRx patient sample included non-T2D users, potentially for off-label weight-loss benefits despite the sole indication of GLP-1 RAs for T2D. Further, lack of clinical data limited our ability to adjust for confounding factors. Both EMR and LRx lack the ability to identify patient mortality. The SE data provide more comprehensive insight into treatment patterns given the national pharmacy data and identification of patient mortality. No assumptions can be made about actual filling of prescriptions (EMR) or consumption of all of the medication supplied in each prescription on time. Lastly, our study was subjected to the same limitations that are often inherent in retrospective claims-based analyses. Our results can only establish associations and not cause-and-effect relationships. Our sample may be biased towards a healthier population due to our continuous enrollment requirements, which were necessary to ensure adequate visibility into the patients’ clinical history; this may be less of an issue among patients with chronic diseases, such as diabetes. Further, small sample sizes for some cohorts/databases limited comparisons.

Few studies have compared treatment patterns and ADD between GLP-1 RA therapies. Miller et al. [13] compared exBID and LIRA treatment patterns using the GE EMR database. Patients were identified initiating therapies of interest between January 2009 and April 2010 with ≥90-day post-index follow-up. Mean ADD was 16.7 µg for exBID and 1.43 mg for LIRA, while in our GE EMR analysis, we found a higher ADD for exBID, 17.7 µg, and a similar ADD for LIRA, 1.44 mg. In addition, based on Cox PHM estimates in the Miller et al. [13] study, index therapy was not a statistically significant predictor of time to treatment modification. In our model for time to stopping (discontinuation or switch), LIRA was associated with a lower risk of stop. Differences between study results may be partially explained by different study periods as our analysis utilized longer-follow-up for LIRA following its approval in Europe in 2009. McDonell et al. [12] examined the real-world daily usage of exBID and LIRA using UK LRx between November 2008 and March 2011 in a similar analysis of ADD using an aggregate approach. The average daily usage was estimated at 20.49 µg for exBID and 1.50 mg for LIRA. We found similar results with an overall ADD of 20.73 µg for exBID and 1.49 mg for LIRA. Using LRx in GE, Fuchs et al. [14] found a mean ADD of 1.29 mg excluding extreme values and 1.42 mg including extreme values for LIRA; while the latter is closer to our observed ADD of 1.44 mg in GE EMR and 1.40 mg in GE LRx, our methods varied (trimming of extreme values vs. trimming months with N < 30 patients). Additionally, Fuchs et al. [14] captured an earlier time period (2009–2010).

Conclusions

Our study is the first, to our knowledge, to comprehensively examine treatment patterns and ADD of GLP-1 RA therapies, including exQW, across various EU countries and datasets. In this real-world analysis, ADD was within indicated label ranges for GLP-1 RA therapies. Treatment patterns varied among GLP-1 RA patients in the sample of European countries considered in this study, with persistence highest among either LIRA or exQW across countries, and lowest among exBID. Longer-term data would be useful to further elucidate practice patterns associated with these medicines, particularly exQW.

References

International Diabetes Federation. IDF Diabetes Atlas. 6th ed. Brussels: International Diabetes Federation; 2013. http://www.idf.org/diabetesatlas. Accessed February 18, 2014.

Inzucchi SE, Bergenstal RM, Buse JB, et al. Management of hyperglycemia in type 2 diabetes: a patient-centered approach: position statement of the American Diabetes Association (ADA) and the European Association for the Study of Diabetes (EASD). Diabetes Care. 2012;35:1364–79.

Egan AG, Blind E, Dunder K, et al. Pancreatic safety of incretin-based drugs—FDA and EMA assessment. N Engl J Med. 2014;370:794–7.

Byetta: EPAR—European Medicines Agency—Europa, European Medicines Agency. http://www.ema.europa.eu/docs/en_GB/document_library/EPAR_-Product_Information/human/000698/WC500051845.pdf (2011). Accessed March 28, 2013.

Victoza: EPAR—Product Information—European Medicines Agency. European Medicines Agency. http://www.ema.europa.eu/docs/en_GB/document_library/EPAR_-Product_Information/human/001026/WC500050017.pdf (2014). Accessed October 21, 2014.

European Medicines Agency: Assessment report for Victoza. http://www.ema.europa.eu/docs/en_GB/document_library/EPAR_-_Public_assessment_report/human/001026/WC500050016.pdf. Accessed September 16, 2013.

Type 2 Diabetes—newer agents (partial update of CG66) (CG87): NICE clinical guidelines. http://publications.nice.org.uk/type-2-diabetes-cg87 (2009). Accessed February 20, 2013.

Bydureon : EPAR—Product information—European Medicines Agency. European Medicines Agency. http://www.ema.europa.eu/docs/en_GB/document_library/EPAR_-_Product_Information/human/002020/WC500108241.pdf (2011). Accessed March 12, 2013.

GLP-1-agonisten: MedicijnBalans. http://medicijnbalans.nl/medicijngroepen/diabetes-type-2/middel/99 (2014). Accessed October 21, 2014.

National Guidelines for Diabetes Care—summary. Socialstyrelsen. http://www.socialstyrelsen.se/nationalguidelines/nationalguidelinesfordiabetescare (2010). Accessed February 12, 2014.

Scheen AJ, Van Gaal LF. Liraglutide (Victoza): human glucagon-like peptide-1 used in once daily injection for the treatment of type 2 diabetes. Rev Med Liege. 2010;65:464–70.

McDonell A, Zammit DC, Haslam T, et al. PDB35 estimating the real life daily usage and daily cost of GLP-1 receptor agonists in the UK setting. Value Health. 2011;14:A477–8.

Miller LA, Burudpakdee C, Zagar A, et al. Exenatide BID and liraglutide QD treatment patterns among type 2 diabetes patients in Germany. J Med Econ. 2012;15:746–57.

Fuchs S, Kostev L, Seitz L, Wohlleben M. Ermittlung der tatsächlichen Tagesdosierung von Liraglutid (PDD) unter realen Versorgungsbedingungen im Hinblick auf die Berechnung von Tagestherapiekosten. Diabetologie und Stoffwechsel. 2011;6:P234.

Buitenhuis R. Impact of a restrictive reimbursement policy on access, costs and quality and safety of treatment: Analysis of a Dutch reimbursement case regarding GLP-1 therapy. Masters thesis, Erasmus University, Rotterdam. http://thesis.eur.nl/pub/12738/Buitenhuis%20R%20351371.pdf (2012). Accessed September 22, 2014.

Decision Resources: European physician and payer forum. DPP-IV inhibitors and GLP-1 analogues for Type 2 diabetes—how are physician and payer perspectives shaping the European markets? http://decisionresources.com/Products-and-Services/Report?r=pforeu0611 (2011). Accessed September 23, 2014.

Acknowledgments

This study and article processing charges were financially supported by Eli Lilly and Company, Indianapolis, IN, USA. All named authors met the ICMJE criteria for authorship for this manuscript, take responsibility for the integrity of the work as a whole, and have given final approval to the version to be published. Mitch DeKoven, Nebibe Varol, Won Chan Lee, Matthew Reaney were involved in study conception, all authors were involved in study design, Mitch DeKoven, Shawn Hallinan, Sara Bruce Wirta were involved in data acquisition, Victoria Divino, Shawn Hallinan, and Sara Bruce Wirta were involved in data analysis, Victoria Divino, Mitch DeKoven, Nebibe Varol, Matthew Reaney, Sara Bruce Wirta were involved in data interpretation, Victoria Divino drafted the manuscript, all authors reviewed, edited and provided final approval of the manuscript. The authors thank Hartmut Richter and Lara Lucchese, employees of IMS Health, who were also involved in data analysis.

Conflict of interest

Nebibe Varol is an employee of Lilly. Matthew Reaney was an employee of Lilly at the time of the study. Victoria Divino is an employee of IMS Health. Mitch DeKoven is an employee of IMS Health. Sara Bruce Wirta is an employee of IMS Health. Shawn Hallinan was an employee of IMS Health at the time of the study. Won Chan Lee was an employee of IMS Health at the time of the study. IMS Health received consulting fees from Lilly for this study.

Compliance with ethics guidelines

This study involved a retrospective cohort analysis using eight databases, and the analysis does not contain studies with human or animal subjects performed by any of the authors. Research ethics approval was received from the regional Ethics Review Board in Stockholm in order to conduct the Swedish analysis. Ethics approval was not required in the other countries.

Open Access

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and the source are credited.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0), which permits use, duplication, adaptation, distribution, and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Divino, V., DeKoven, M., Hallinan, S. et al. Glucagon-Like Peptide-1 Receptor Agonist Treatment Patterns Among Type 2 Diabetes Patients in Six European Countries. Diabetes Ther 5, 499–520 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1007/s13300-014-0087-6

Received:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s13300-014-0087-6