Abstract

Introduction

Nonmedical use of prescription opioid analgesics is associated with epidemic levels of morbidity and mortality. There are several factors that affect the abuse liability of the various opioids, including likability or the pleasurable subjective effects. Due to rising public health concerns over escalating prescription opioid abuse, we sought to examine the literature about abuse liability with a specific focus on likability studies.

Methods

A search of EMBASE and MEDLINE databases identified articles that described the comparative likeability and/or abuse potential of hydrocodone and oxycodone relative to each other and/or of either one to morphine. After an assessment of study quality using the Oxford/Jadad scale, relevant details such as demographics, study design, and outcome measures were compiled into an evidence table.

Results

We identified nine studies that met inclusion criteria. All were double-blinded, randomized, placebo-controlled crossover studies and scored 5 out of 5 Jadad scale. There was no consistent clinically significant difference between abuse liability of morphine and hydrocodone. Oxycodone demonstrated high abuse liability on the basis of its high likability scores and a relative lack of negative subjective effects.

Conclusion

Oral oxycodone has an elevated abuse liability profile compared to oral morphine and hydrocodone.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The USA is witnessing a burgeoning epidemic of nonmedical prescription opioid use associated with escalating rates of addiction, mortality, and economic loss [1]. Prescription opioids are a group of morphine-like analgesics that share clinical effects despite distinct pharmacological properties. The term “nonmedical users” refers to patients who use opioids in ways not directly intended by the prescriber and includes those who abuse the opioids for recreational purposes.

With the current options and ready availability of opioids, factors beyond availability become relevant to the evaluation of user preference. Such characteristics comprise a drug's pharmacological properties including onset or duration; mode of administration; adverse effects, such as nausea or flushing; or the desired psychoactive effects. The abuse liability of a drug characterizes its net positive and negative subjective effects and thus the likelihood of being used for recreational purposes. The term “likeability” generally represents the positive psychoactive component of a drug's subjective effects.

Although nearly all mu opioid receptor agonists are euphorigenic, select opioids are preferred among the abusing population. Therapeutically relevant pharmacological classifications, such as potency or duration of action, are not completely predictive of abuse liability. However, abuse liability can be inferred based on street price, pharmacy theft rates, drugs leading to treatment access [2], and overdose morbidity and mortality data [3]. For example, although threefold more hydrocodone than oxycodone tablets are sold [4], the latter is proportionally responsible for a much greater incidence of ED visits associated with nonmedical use [3]. This suggests that oxycodone is preferentially used for recreational purposes.

Due to rising public health concerns over escalating prescription opioid abuse, we sought to examine the literature about abuse liability with a specific focus on likability studies. We chose to compare two of the most widely prescribed oral opioids, hydrocodone and oxycodone, to each other and/or to morphine in order to assess abuse liability.

Methods

A search of the English language medical literature was performed using MEDLINE and EMBASE databases to identify empirical literature using the independent terms “opioid likeability” and “opioid abuse liability.” Both terms were included due to the inconsistency in the design and terminology among relevant studies. This was supplemented by a manual review of the reference lists to identify gray literature, which include publications and other documents from federal offices, government agencies, and professional societies. The search results were subsequently limited to articles that specifically described the comparative likeability and/or abuse potential of hydrocodone and oxycodone relative to each other and/or of either one to morphine. Relevant articles were screened in a structured iterative process and additional literature search performed based on citations from pertinent articles. All articles used in the formulation of this clinical policy were graded by at least two authors using the Oxford/Jadad scoring system [5]. This system was applied to assess blinding, randomization, and withdrawal/dropouts and was used to assess the general quality of the selected research. Agreement was met among the reviewers on the score given to each respective publication.

Information from relevant articles was manually entered into a spreadsheet that contained details of target population demographics, study design typology, outcome measures (such as likeability), and funding source (Table 1). We collected data on formulation (e.g., immediate release vs. sustained release), route of administration (oral (PO) vs. intravenous (IV)), reported positive and negative effects, physiological effects when mentioned, method of evaluating abuse potential or likeability (e.g., visual analogue scales (VAS), the Addiction Research Center Inventory (ARCI), adjective opioid ratings scales, subjective questionnaires involving drug effect/liking/take again, breakpoint values drug vs. money, drug preference questionnaires), and funding source. Due to the lack of standardization of research studies and instrumentation, a meta-analysis was not feasible. Data were interpreted across a heterogeneous group of publications; thus, an integrated approach towards findings and objectives were extracted from the manuscript to form a review.

Because the definition of positive and negative effects varied by study, we included as positive effects terms such as: euphoria, feel good, feeling high, carefree, coasting, dreamy, mellow, social, stimulated, pleasant thoughts, and pleasant bodily sensations. Similarly, terms defined as negative effects included: dysphoria, dislike, feeling irritable, dizzy, difficult to concentrate, headache, dry mouth, flushing, gastrointestinal distress, feeling heavy, sluggish, and unpleasant thoughts and bodily sensations. Outcome measures of increased abuse liability were based on high subjective ratings for positive effects (e.g., likeability) and low subjective ratings for negative effects. The reinforcing effect of an opioid was variably defined and quantified, in different methodologies, as either the desire to “take again” or was based on participant willingness to pay a specified amount (in dollars) for a drug.

Results

Seventeen studies were found initially that met search criteria, and further review identified that nine met inclusion criteria. The primary reason for exclusion of a study was lack of an active comparator group to either the other semisynthetic opioid or to morphine. All identified studies were double-blinded, randomized, control crossover studies. All scored 5 out of 5 on the Oxford/Jadad scale for quality (Table 1). Seven of the studies used exclusively subjects who had a history of opioid use or abuse. The studies varied in the dose form used and route of administration (PO vs. IV), as well as the other opioids included in the assessment (Table 1).

Subjective effects of opioid products were determined using VAS, ARCI, and the adjective opioid ratings scales. Some studies included questionnaires involving reinforcement data including drug effect, liking, and take again [6–9]. One study directly assessed breakpoint values of participants' desire for drug vs. money [10]. Additionally, studies included objective physiologic data and performance batteries to assess timing of onset, duration, and extent of opioid affects (Table 1).

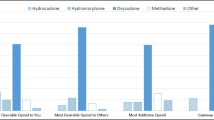

Multiple studies, largely from a single research group, found no clinically significant difference between abuse liability of morphine and hydrocodone. Both hydrocodone and morphine demonstrated similar subjective positive and negative effects [6, 8]. This same pattern was identified when comparing extended-release morphine and immediate-release hydrocodone preparations [11]. In these studies, hydrocodone did not demonstrate reinforcing effects or statistically significant abuse liability. Moreover, oxycodone demonstrated high subjective attractiveness ratings and a paucity of negative ratings across the majority of studies assessed [7, 9, 10, 12]. Oxycodone also demonstrated significantly increased reinforcing characteristics. “Take again” ratings were consistently higher for oxycodone than morphine [6, 10].

One study found no substantial difference in subjective effects related to likability of oxycodone, hydrocodone, and hydromorphone, but did demonstrate increased risk of abuse over placebo for all three opioid products assessed [13]. A similar study comparing oxycodone and hydrocodone to placebo found that peak liking ratings were significantly greater with oxycodone compared to placebo, and those of hydrocodone were not [14]. Most studies that included morphine used morphine as a gold standard opioid and differentiated the abuse potential of morphine vs. the newer opioid drugs. None of the randomized controlled trials that included morphine found statistically significant abuse potential or reinforcing effects of morphine [6, 8, 9]. At high doses, morphine was found to have predominantly dysphoric effects and increased negative side effects including dry mouth and flushing [8, 9]. Mean 24-h “take again” ratings in one study indicated that in recreational drug users, morphine was less likely to be “wanted” or taken again than placebo [8].

Discussion

At a national level, hydrocodone and oxycodone are the most frequently prescribed opioid analgesics and have the highest level of abuse of any prescription medication [3, 4]. Our literature review demonstrated that oxycodone has a substantially elevated abuse liability profile due to high likability scores and far fewer negative subjective effects. Our findings are consistent with previous epidemiologic and ethnographic studies that suggest that oxycodone is favored over hydrocodone. When patients with a history of abuse are queried about their choice of opioids, abusers preferred oxycodone over other opioids [15].

The route of administration in the reviewed studies was generally oral. Prior work has shown that abusers of hydrocodone and oxycodone typically took medication orally, the route intended for use, whereas morphine abusers more often injected PO morphine formulations [16]. Since progression to intravenous use is not uncommon among prescription opioid users, we included the two studies that evaluated the comparative effects of the selected opioids administered intravenously. Results of one study suggested that all three opioids produce subjectively similar effects and are all of equal abuse potential when given by this route [12]. Both semisynthetic opioids produced markedly less negative effects that morphine. No studies could be found that compared the abuse potential of the same opioid agent via multiple routes.

Abuse liability of opioid analgesics reflects a combination of factors, but availability likely maintains the greatest impact on the opioid choice of abuse for an individual or population. For example, although opium has been abused for centuries, the isolation of morphine leads to its preferential widespread abuse. The subsequent derivatization of morphine to form heroin essentially displaced morphine abuse at the beginning of the twentieth century. Those intent on opioid abuse now have multiple options due to the development of additional semisynthetic, and fully synthetic, opioids that are in pharmaceutical grade drugs. Ultimately, healthcare providers are the source of most of these drugs, which has resulted in this new trend of prescription opioid misuse and abuse.

The data we reviewed suggest that there is less abuse potential associated with the use of hydrocodone and morphine than with oxycodone. This supports the recent implementation in Washington State and other regions of the “oxy-free” emergency department [17].

Limitations

The studies were quite diverse, not standardized methodologically, using mixed approaches and distinct assessment tools. The studies reviewed compared different patient populations (e.g., recreational opioid users, abusers, and naïve subjects), using different routes of administration, with varying preparations (e.g., containing acetaminophen), and used varying assessments for physiological effects (e.g., pupil size). Only one of the studies reviewed addressed the use of opioid in patients with chronic pain [11]. The studies typically involved only a small sample size, and studies were performed under laboratory, not real-world, conditions. Additionally, since most patients had prior opioid exposure, adverse and negative effects of opioids are likely to be higher in opioid-naïve patients, so the relative negative effects of some of these opioids may be more significant in opioid-naïve patients and may highlight the “likeability” of drugs with fewer negative effects (e.g., oxycodone) with first-time exposure.

In this study, likability is equated with abuse liability. Outside the laboratory setting, abuse liability is not solely dependent on likability; factors such as price, availability, previous exposure, formulation, and route of administration also play a role in determining potential for abuse. The studies reviewed attempted to eliminate these outside factors to isolate likability and directly assess abuse liability. We primarily examined studies evaluating immediate-release formulations of the specified short-acting opioids, but many abusers use extended-release preparations of these opioids. However, until recently, some of these extended-release formulations could be converted to immediate-release formulations by mechanical means such as crushing. The use of tamper-resistant formulations, which are designed to impede modification, should reduce use by this means [18]. A recent analysis of self-reported substance use by patients admitted to treatment facilities since the switch to tamper-resistant oxycodone ER (Oxycontin and generic) has demonstrated a change back to short-acting oxycodone and possibly heroin [19]. Interestingly, the FDA allows label claims for abuse deterrence based on several criteria, one of which is the relative likeability of one product compared to older formulations of the drug. However, no opioid analgesic to date has received approval to use this claim. Although 6/17 of the originally selected articles were funded by pharmaceutical companies, only one of the studies included had such funding [10]. Although this was not designed by intent, industry funding may have led to research methodologies that did not fit our specific criteria.

Conclusion

Oral oxycodone has a substantially elevated abuse liability profile compared to oral morphine and hydrocodone due to high likability scores and a relative lack of negative subjective effects.

References

Gilson AM, Kreis PG (2009) The burden of the nonmedical use of prescription opioid analgesics. Pain Med 10(Suppl 2):S89–S100

Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (2012) TEDS–Treatment Episode Data Set. At http://wwwdasis.samhsa.gov/webt/information.htm. Accessed 11 Aug. 2012

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) (2010) Emergency department visits involving nonmedical use of selected prescription drugs—United States, 2004–2008. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 59(23):705–709

IMS Institute for Healthcare Informatics (2011) The use of medicines in the United States: review of 2010. pp 1–37

Jadad AR, Moore RA, Carroll D, Jenkinson C, Reynolds DJ, Gavaghan DJ, McQuay HJ (1996) Assessing the quality of reports of randomized clinical trials: is blinding necessary? Control Clin Trials 17(1):1–12

Zacny JP (2003) Characterizing the subjective, psychomotor, and physiological effects of a hydrocodone combination product (Hycodan) in non-drug-abusing volunteers. Psychopharmacology 165(2):146–156

Zacny JP, Gutierrez S (2003) Characterizing the subjective, psychomotor, and physiological effects of oral oxycodone in non-drug-abusing volunteers. Psychopharmacology 170(3):242–254

Zacny JP, Gutierrez S, Bolbolan SA (2005) Profiling the subjective, psychomotor, and physiological effects of a hydrocodone/acetaminophen product in recreational drug users. Drug Alcohol Depend 78(3):243–252

Zacny JP, Lichtor SA (2008) Within-subject comparison of the psychopharmacological profiles of oral oxycodone and oral morphine in non-drug-abusing volunteers. Psychopharmacology 196(1):105–116

Comer SD, Sullivan MA, Whittington RA, Vosburg SK, Kowalczyk WJ (2008) Abuse liability of prescription opioids compared to heroin in morphine-maintained heroin abusers. Neuropsychopharmacology 33(5):1179–1191

Wilsey BL, Fishman S, Li C-S, Storment J, Albanese A (2009) Markers of abuse liability of short- vs long-acting opioids in chronic pain patients: a randomized cross-over trial. Pharmacol Biochem Behav 94(1):98–107

Stoops WW, Hatton KW, Lofwall MR, Nuzzo PA, Walsh SL (2010) Intravenous oxycodone, hydrocodone, and morphine in recreational opioid users: abuse potential and relative potencies. Psychopharmacology 212(2):193–203

Walsh SL, Nuzzo PA, Lofwall MR, Holtman JR Jr (2008) The relative abuse liability of oral oxycodone, hydrocodone and hydromorphone assessed in prescription opioid abusers. Drug Alcohol Depend 98(3):191–202

Zacny JP, Gutierrez S (2009) Within-subject comparison of the psychopharmacological profiles of oral hydrocodone and oxycodone combination products in non-drug-abusing volunteers. Drug Alcohol Depend 101(1–2):107–114

Cicero TJ, Ellis MS, Paradis A, Ortbal Z (2010) Determinants of fentanyl and other potent μ opioid agonist misuse in opioid-dependent individuals. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf 19(10):1057–1063

Butler SF, Black RA, Cassidy TA, Dailey TM, Budman SH (2011) Abuse risks and routes of administration of different prescription opioid compounds and formulations. Harm Reduct J 8(1):29

Anonymous (2010) New guidelines create an “Oxy-free” ED. ED Manag 22(12):136–137

Raffa RB, Pergolizzi JV (2010) Opioid formulations designed to resist/deter abuse. Drugs 70(13):1657–1675

Cicero TJ, Ellis MS, Surratt HL (2012) Effect of abuse-deterrent formulation of OxyContin. N Engl J Med 367(2):187–189

Funding Sources

None

Conflict of Interest

None

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Wightman, R., Perrone, J., Portelli, I. et al. Likeability and Abuse Liability of Commonly Prescribed Opioids. J. Med. Toxicol. 8, 335–340 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1007/s13181-012-0263-x

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s13181-012-0263-x