Abstract

Mental toughness refers to a collection of psychological characteristic which are central to optimal performance. Athletes, coaches, and sport psychologists have consistently implicated mental toughness as one of the most important psychological characteristics related to success in sports. Over the last few decades, numerous studies have been conducted to examine the role of mental toughness in sporting success. However, its conceptualization and measurement are without consensus. The purpose of this study is to systematically review some of the emerging definitions and conceptualizations, and examine how mental toughness could be nurtured. This review considers both qualitative and quantitative approaches to the study of mental toughness with the specific focus on the models and the development of the measurement of this construct. Although these discussions center on the general aspects of mental toughness, we believe many of the issues have relevance to scholars and practitioners who are interested in the measurement of psychological variables as they pertain to sport, exercise, and other performance or achievement contexts.

Zusammenfassung

Mentale Stärke zählt zu einer Reihe psychologischer Fähigkeiten, die wichtig für optimale Leistung sind. Durchgängig verweisen Sportler, Trainer und Sportpsychologen auf mentale Stärke als eine der wichtigsten psychologischen Fähigkeiten für den Erfolg im Sport. Deshalb wurden über die letzten Jahrzehnte viele Untersuchungen zur Bedeutung von mentaler Stärke für den sportlichen Erfolg durchgeführt. Es besteht jedoch kein Konsens bezüglich der Konzeptualisierung und Erfassung dieser Fähigkeit. Ziel der vorliegenden Studie ist es, einen systematischen Überblick über Definitionen und Konzeptualisierungen zu geben und zu betrachten, wie mentale Stärke verbessert werden kann. Die Übersicht berücksichtigt qualitative und quantitative Ansätze zur Untersuchung von mentaler Stärke mit einem speziellen Fokus auf Modellen und der Entwicklung von Messinstrumenten für dieses Konstrukt. Zwar konzentriert sich diese Betrachtung auf allgemeine Aspekte von mentaler Stärke, wir glauben aber, dass viele dieser Fragen relevant für Wissenschaftler und Praktiker sind, die an der Erfassung von psychologischen Variablen interessiert sind, da sie mit Sport, körperlicher Aktivität und anderen Kontexten der Leistungserbringung in Verbindung stehen.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Athletes’ success or failure is multifactorial. It depends on the combination of many factors including physical, tactical, technical and psychological factors. The psychological factor is usually the determinant that differentiates a winner and a loser in sports (Brewer, 2009). For example, Weinberg and Gould (2003) indicated that mental ability contributed over 50% in athletes’ success when competing against the opponents. In addition, Gould, Hodge, Peterson, and Petlichkoff (1987) stated that mental toughness was the most important for success in wrestling (rated as 82%). In a study involving ten Olympians, they reported mental toughness is one of the highest ranked psychological characteristics that determine at successful performance (Gould, Dieffenbach, & Moffett, 2002). However, despite its frequent use, the term mental toughness remains subjective. Specifically, it is often used to describe a broad term that reflects the ability of an athlete to cope effectively with training and competition demands in an effort to remain resilient (Bull, Shambrook, James, & Brooks, 2005; Connaughton et al., 2008; Fourie & Potgieter, 2001; Jones, Hanton, & Connaughton, 2007; Thelwell, Weston, & Greenlees, 2005).

Athletes, coaches, and applied sports psychologists have consistently referred to mental toughness as one of the most important psychological characteristics related to outcomes and success in the elite sport. However, it is probably one of the least understood terms used in applied sport psychology (Jones, Hanton, & Connaughton, 2002). This is partly due to a wide variety of definitions, measurements and research designs used when researching this construct. In order to facilitate further understanding of this construct, a sport-specific use of this terminology is warranted. The purpose of this manuscript is to review those studies examining the construct of mental toughness and its relationship to sports performance. This review is divided into four specific sections including the early views on mental toughness, contemporary mental toughness research applying qualitative approaches, contemporary mental toughness research using quantitative approaches, and research on the relationship between mental toughness and other psychological variables. Conclusion and future research recommendations in these areas are also discussed.

Method

Search strategy

A literature search was conducted using major computerized databases (e.g. PubMed, ScienceDirect and Scopus) and library holdings for peer-reviewed articles in the English language and were rechecked by another two co-authors. The keywords used in this review were mental toughness, sport and athlete. A manual search of the reference lists in the relevant studies found in the computerized search was also performed.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

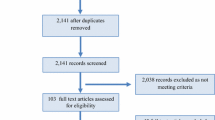

The inclusion of articles followed a three-phased approach (Fig. 1) using Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines (Moher et al., 2015). In the first phase, the 1311 records were initially obtained through extensive database searching. In all, 57 duplicates were identified and removed in this phase. In the second phase, the titles of 1254 records were screened, and records were removed if they did not refer to the following terms (or close variants of such): mental toughness, sport, athlete. This process resulted in the removal of 1093 records. In the third phase, the full-texts of the final 161 records were examined. Records that met the inclusion criteria were studies that: (a) used the mental toughness in the study; (b) were conducted in a sport context; and (c) were written in English. A total of 14 studies met the inclusion criteria, and these were included in the review.

Categorization of studies

The studies included in this review have been divided into four major broad categories. The first category comprises studies which involved the early conceptualization of mental toughness. The second category consists of studies that utilized qualitative approaches on mental toughness. The third category includes studies that used quantitative approaches. This review considers both qualitative and quantitative approaches to the study of mental toughness with the specific focus on the models and the development of the measurement of this construct (all studies summarized in Table 1). Finally, the forth category reviewed research on the relationship between mental toughness and other psychological variables.

Early conceptualization of mental toughness

The first academic reference to the concept of mental toughness was proposed by Cattell, Blewett, and Beloff (1955) who suggested ‘tough-mindedness’ as a culturally or environmentally determined personality trait fundamental to individual success. Purported to be one of sixteen primary traits that described personality, Cattell (1957) viewed tough-minded individuals as self-reliant, realistic and responsible, and contrasted this with emotional sensitivity. This position was supported by suggestions that “the athlete who is mentally tough is somewhat insensitive to the feelings and problems of others” (Tutko & Richards, 1971), and that “being able to handle pressure off the field can help you be mentally tough on it” (Tapp, 1991). Whilst others supported the notion that mental toughness was a personality trait (Kroll, 1967; Werner & Gottheil, 1966), others have challenged this (Dennis, 1978), with some purporting that the construct is simply a state of mind (Gibson, 1998) or even just a set of psychological characteristics (Bull, Albinson, & Shambrook, 1996).

Most elite athletes contended that at least 50% of their superior athletic performance was the result of mental or psychological factors that reflected the phenomenon of mental toughness (Loehr, 1982, 1986), whereas 83% of wrestling coaches rated it as the most important psychological characteristics for determining competitive success (Gould et al., 1987). The extensive work of Loehr (1982, 1986) who advocated that mental toughness is an attribute of those who respond to problems, pressure, making mistakes and competition with the right attitude. According to Loehr (1986), mentally tough performers are disciplined thinkers who respond to pressure in ways which enables them to remain feeling relaxed, calm and energized simply because of the ability to sustain positive energy flow despite adversity. In addition, Loehr (1986) published a model of mental toughness that included seven characteristics: self-confidence, negative energy, attention control, visual and imagery control, motivation, positive energy, and attitude control. Although this model is conceptually appealing, Loehr did not provide a rationale for the selection of the seven mental toughness factors. However, Loehr (1995) pointed out that mental toughness can be developed and acquired, and not just innate genetic traits (Gucciardi et al., 2009).

Crust (2007) noted that one point of contention in the literature had been related to whether mental toughness is conceptualized as an inherited, innate personality characteristic or if the acquisition of mental toughness is believed to be due more to environmental factors and learning. In addition, these studies are not based on rigorous theoretical and scientific methods. The limitations of earlier studies reflect the development of mental toughness in the future. Therefore, contemporary research begins to explore the definition and characteristics of mental toughness with qualitative and quantitative research patterns. The next section focuses on the qualitative approaches to the study of mental toughness.

Qualitative approaches to the study of mental toughness

In a pioneering qualitative study of mental toughness, Fourie and Potgieter (2001) analyzsd written responses from 131 expert coaches and 160 elite athletes. Coaches and elite athletes responded to a series of open-ended questions requiring them to provide their best definitions and descriptions of mental toughness. They identified twelve components of mental toughness, including motivation level, coping skills, confidence maintenance, cognitive skills, discipline and goal-directedness, competitiveness, possession of prerequisite physical and mental requirements, team unity, preparation skills, psychological hardiness, and ethics. Drawing from these responses, they recognized the subjective interpretation of the way coaches and athletes described characteristics of mental toughness. For this reason, the researchers concluded that further work was needed to bring about a more objective description and model of mental toughness (Fourie & Potgieter, 2001).

In another qualitative study, Jones et al. (2002) employed Kelly’s (1955) personal construct theory to understand how mental toughness is construed. In brief, this theory focuses on both the uniqueness of the individual and the processes common to all people. Furthermore, personal construct theory proposes that individuals strive to understand, interpret, anticipate, and control the world of experience in order to deal effectively with it (Kelly, 1955). Using data from ten elite international athletes, Jones et al. (2002) proposed that mental toughness is having the natural or developed psychological edge that enables athletes to (1) generally cope better than the opponents with the many sports demands (competition, training, lifestyle); and (2) specifically more consistent and better than the opponents in staying determined, focused, confident, and in control under pressure.

As a result of an inductive thematic content analysis, Jones et al. (2002) identified twelve key attributes of mental toughness including having an unshakable self-belief in one’ ability to achieve your competition goals; bouncing back from performance setbacks as a result of increased determination to succeed; having an unshakable self-belief that one’s possess unique qualities and abilities; having an insatiable desire and internalized motives to succeed; remaining fully-focused on the task at hand in the face of competition-specific distractions; regaining psychological control following competition-specific unexpected and uncontrollable events; pushing back the boundaries of physical and emotional pain, while still maintaining technique and effort under distress (in training and competition); accepting that competition anxiety is inevitable and knowing that one can cope with it; thriving on the pressure of competition; not being adversely affected by others’ good and bad performances; remaining fully-focused in the face of personal life distractions; and switching a sport focus on and off as required. These related to performance and lifestyle-related focus, self-belief, desire and motivation and how a mentally tough performer deals with the pressure (external), anxiety (internal) and the hardship associated with superior performance (i.e., physical and emotional pain).

A limitation in early mental toughness research is its general conceptualization of the construct of mental toughness. One of the studies that attempt to address this is the study of mental toughness specific to cricket players (Bull et al., 2005). The two main issues Bull et al. (2005) addressed in their study were the following: to obtain a better understanding of what mental toughness is for cricketers and to identify how cricketers developed their mental toughness. They used qualitative procedures to interview 12 mentally tough cricketers. The participants were drawn from a total of 101 English cricketers whom were identified by coaches as being the most mentally tough cricketers of the previous 20 years in English cricket. From their results, they presented a model of mental toughness that included four structural categories, each containing a number of themes related to overall mental toughness. These include environmental influence: parents, childhood, the need to earn success, opportunities to survive early setbacks, exposure to foreign cricket; tough character: resilient confidence, independence, self-reflection, competitiveness with self as well as others; tough attitudes: never-say-die mindset, go-the-extra-mile mindset, thrive on competition, belief in making a difference, exploit learning opportunities, willing to take risks, belief in quality preparation, determination to make the most of ability, self-set challenging targets; and tough thinking: thinking clearly–making good decisions, keeping perspective, honest self-appraisal and robust self-confidence–overcoming self-doubts, feeding off physical conditioning, maintaining self-focus (Bull et al., 2005).

In another study involving male professional soccer players, Thelwell et al. (2005) asked the players to compare their soccer-specific definition and their understanding of mental toughness with that proposed by Jones et al. (2007). The soccer players viewed mental toughness as enabling players to “always” cope better than their opponents rather than “generally” cope better. Likewise, they identified only ten attributes as opposed to the twelve attributes of mental toughness by Jones et al. (2007). Those attributes included the following: having total self-belief at all times that one will achieve success; wanting the ball/wanting to be involved at all times; having the ability to react to situations positively; having the ability to hang on and be calm under pressure; knowing what it takes to grind oneself out of trouble; having the ability to ignore distractions and remain focused; controlling emotions throughout performance; having a presence that affects opponents; having everything outside of the game in control, and enjoying the pressure associated with performance (Thelwell et al., 2005).

In 2007, Jones et al. conducted a follow-up study using a sample of super-elite sports performers (i.e., Olympic/World Champions) to expand the mental toughness knowledge base and broadened the scope by including the perceptions of coaches and sport psychologists who had coached and consulted at that level. The results mirrored their earlier definition of mental toughness. Moreover, they also extended the list of attributes considered essential to the make-up of mental toughness to 30. These were subsequently categorized into 13 subcomponents of mental toughness, which were then organized into a framework of mental toughness comprising four dimensions; a general Attitude/mindset dimension, and three time-specific dimensions, Training, Competition, and Post-competition (Jones et al., 2007).

In an attempt to propose a more specific definition of mental toughness, Gucciardi et al. (2009) employed Kelly’s (1955, 1991) Personal Construct Psychology (PCP) and proposed mental toughness as “a collection of experientially developed and inherent sport-specific and sport-general values, attitudes, behaviours, and emotions that influence the way in which an individual approaches, responds to, and appraises both negatively and positively construed pressures, challenges and adversities to consistently achieve his or her goals” (p. 278). Whilst Gucciardi et al. (2008) did not offer a definitive perspective on the key values, attitudes, cognitions and emotions, investigations into the sport-specific components of mental toughness related to Australian rules football (Gucciardi et al., 2008), cricket (Gucciardi & Gordon, 2009) and soccer (Coulter, Mallett, & Gucciardi, 2010), highlighting the emergence of a core group of key mental toughness facets that do not vary significantly by sport (e.g., self-belief, self-motive, attention control, resilience).

Mental toughness research using quantitative approaches

One of the key differences between a qualitative and a quantitative approach is the used of instruments to quantify the data. In this regard, following his conceptualization of mental toughness, Loehr (1986) constructed the Psychological Performance Inventory (PPI). Loehr (1982) suggested that mentally tough athletes learned or developed two important skills: first, the ability to increase their flow of positive energy when faced with adversity or a crisis; and second, to think in ways that promote the right attitudes to solve problems, or to deal with pressure, mistakes, or competition. The PPI contains 42 items and measures mental toughness which is conceptualized to have seven dimensions; Self-confidence, Negative Energy, Attention Control, Visualization and Imagery Control, Motivation, Positive Energy, and Attitude Control. Each subscale contains six items, each scored on a 5-point Likert scale, with scores for each subscale ranging from 6 to 30, and for total mental toughness ranging from 42 to 210. A number of studies (e.g., Golby, Sheard, & Lavallee, 2003, 2004; Kuan & Roy, 2007; Lee, Shin, Han, & Lee, 1994) have employed the PPI as a measure of mental toughness.

Despite its widespread usage, evidence has emerged suggesting limitations of its psychometric properties. For example, Golby et al. (2007) and Middleton et al. (2004) tested the construct validity of the PPI. For example, using responses from 263 young elite athletes, Middleton et al. (2004) revealed inadequate fit between the hypothesized seven-factor model and the data as well as an improper solution (i.e. factor correlations >1) using confirmatory analysis (CFA). However, some criticism has been levelled at Middleton et al. (2004) study for using a somewhat small sample size (N = 263) for testing construct validity and the limited age range of the sample (12–17 years old). Addressing these limitations, Golby et al. (2007) used a larger sample (N = 408) with a broader age range (12–63 years old) to evaluate the psychometric properties of the PPI, and they reported a similar lack of support for the factorial structure of the PPI. Besides, Gucciardi (2011) also concluded that the psychometric evidence for the hypothesized measurement model of the PPI is not encouraging for its future use.

With the analyses revealing a lack of support for the hypothesized factor structure of the original PPI (1986), Golby et al. (2007) subsequently developed the Psychological Performance Inventory-Alternative (PPI-A), which represents four factors of MT, namely determination, self-belief, positive cognition, and visualization. Golby et al. (2007) used the responses from their original PPI study to generate the PPI-A involving 408 respondents. Using principal component analysis to find structure in their data, they used confirmatory factor analysis to assess the psychometric structure of the model. Collectively satisfying absolute and incremental fit index benchmarks, the inventory possesses satisfactory psychometric properties, with adequate reliability and convergent and discriminant validity. The results lend preliminary support to the factorial validity and reliability of the model.

Sheard (2009) used the PPI-A to investigate national differences in mental toughness between rugby league players in the United Kingdom and Australia. The results from this study indicated that significant differences in mental toughness were apparent between national teams. Although these findings are based on small sample size, Sheard (2009) concluded that these findings provided evidence for the divergent (or discriminant) validity (i.e. does not correlate too much with similar but distinct constructs) of the PPI-A. As alternatives to PPI and PPI-A, Clough et al. (2002) developed the Mental Toughness Questionnaire 48 (MTQ 48) consistent with their model of mental toughness. Reflecting the name, the MTQ 48 contains 48 items that are scored on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from (1) strongly agree to (5) strongly disagree (Crust & Clough, 2005). It has an overall test–retest coefficient of 0.9, with the internal consistency of the subscales (Control, Commitment, Challenge and Confidence) found to be 0.73, 0.71, 0.71, and 0.8 respectively (Clough et al., 2002). Connaughton et al. (2008), however, advised that the MTQ 48 psychometric properties reported should be interpreted with caution because the rationale for the conceptualization of MT is essentially based on hardiness and confidence constructs. Furthermore, there was no demonstration of validity even if a sound conceptualization was apparent.

Middleton et al. (2005) constructed the Mental Toughness Inventory (MTI) 36-item based on a model of mental toughness developed from themes that emerged from their qualitative study. The MTI was designed to measure the twelve characteristics Middleton et al. (2004) proposed, namely: self-efficacy, future potential, mental self-concept, task familiarity, value, personal best motivation, goal commitment, task-specific attention, perseverance, positivity, positive comparisons, and stress minimization, which are summed to produce a global mental toughness score. The self-report MTI is an 8‑point response scale where respondents rate statements from 1 (not like me) to 8 (like me). Middleton, Martin, and Marsh (2011) reported that the MTI is strong on conceptual grounds with strong psychometric properties and high reliability. However, Sheard (2012) suggested that although the development of MTI is based on a sound theoretical framework, the MTI required independent testing to assess its psychometric properties.

Sheard et al. (2009) then developed the Sport Mental Toughness Questionnaire (SMTQ). Two independent studies supported a three-factor (Confidence, Constancy, and Control) 14-item model for the SMTQ. With a sample of 633 athletes (427 males, 206 females; mean [M] age = 21.5 years; standard deviation [SD] = 5.48), drawn from 25 sports, of international, national, county and provincial, or club and regional standards, the first study focused on item development and exploratory factor analytic techniques to establish the psychometric properties of the SMTQ. The second study sought to confirm the structure obtained in the first study using confirmatory factor analytic techniques with an independent sample of 509 sports performers (351 males, 158 females; M age = 20.2 years; SD = 3.35), competing at the aforementioned standards, and representative of 26 sports. Confirmatory analysis using structural equation modelling confirmed the overall structure. A single factor underlying mental toughness was identified with higher-order exploratory factor analysis using the Schmid-Leiman procedure. Collectively, satisfying absolute and incremental fit-index benchmarks, the inventory was shown to possess satisfactory psychometric properties, with adequate reliability, divergent validity, and discriminative power. The results revealed promising features of the SMTQ, lending preliminary support to the instrument’s factorial validity and reliability. The results revealed promising features of the SMTQ, lending preliminary support to the instrument’s factorial validity and reliability.

Another mental toughness questionnaire is based on the work of Gucciardi et al. (2009). They develop a pool of 60 items for their 11-factor model of mental toughness. Confirmatory factor analysis with 418 footballers revealed that the 11-factor model did not fit the data well. The authors then performed a series of principal component analysis (PCA) using both varimax and promax rotations to explore the usefulness of three-, four-, and five-factor solutions. These analyses led to a 24-item four-factor model (thrive through challenge, sport awareness, tough attitude, desire success), which they labelled the Australian Football Mental Toughness Inventory (AfMTI). However, Gucciardi et al. (2009) found that the 24-item AfMTI did not fit the data with a sample of 350 youth Australian footballers. Gucciardi (2011) concluded that further work is required to address these concerns.

Recognizing the need to capture the context-specific dimension of mental toughness, Gucciardi et al. (2009) conducted a series of studies within a mixed-methods framework to develop their Cricket Mental Toughness Inventory (CMTI). Interviews with 16 cricketers from two countries, five of whom were still involved in international cricket at the time of study to develop another model of mental toughness for cricketers. A six-factor model emerged from the interviews, and two independent focus groups with nine Australian cricketers resulted in minor modifications to the wording and the addition of eight items. Gucciardi et al. (2009) administered the six-factor inventory to a general sample of cricketers from international leagues (n = 570) and a sample of Australian cricketers (n = 433). There was an equal split of the total sample for either a calibration or cross-validation analysis. One factor (i.e., cricket smarts) was removed following a series of confirmatory factor analyses with the calibration sample, which provided support for the 15-item, five-factor model. Gucciardi (2011) found support for the validity of the CMTI measurement model by confirmatory factor analysis and internal reliability analysis. Gucciardi (2011) and Gucciardi et al. (2009) provided preliminary support for the factor structure, internal reliability, and construct validity of the CMTI. Gucciardi (2011) stated that the use of a male sample created some practical issues in the generalizability of the measurement tool across gender and suggested that further conceptual and statistical work would be beneficial before using the CMTI in mental toughness research.

Despite the emergence of alternatives to measure general and sport-specific mental toughness, the existing questionnaire are showing mixed results when tested in a different sample from which they are originally constructed. These mixed findings warrant further investigation into how mental toughness is to be measured.

Research on mental toughness and other psychological variables

Hardiness

Clough et al. (2002) attempted to bridge the gap between theoretical research and applied practice in the study of mental toughness. They placed great emphasis on ecological validity and as such consulted elite athletes and coaches and drew upon their own applied work to gain an applied perspective on mental toughness. Clough et al. (2002) also acknowledged the theoretical work of existential psychologists (Kobasa, 1979; Kobasa, Maddi, & Kahn, 1982) in the field of health psychology and used the related concept of hardiness to transpose research into a more sport-specific setting. According to Clough et al. (2002), hardiness fails “to capture the unique nature of the physical and mental demands of competitive sport” (p. 37).

Previous researchers have reported hardiness to be a subcomponent of mental toughness (Fourie & Potgieter, 2001). It would appear that both hardiness and mental toughness are characterized by resiliency, perseverance, effectively coping with pressure or adversity, motives to achieve success (predominantly intrinsic), and a deep sense of purpose and thus involvement in activities and personal encounters. While finding distinct similarities between coaches’ and athletes’ perceptions of mental toughness and the hardiness construct, Clough et al. (2002) highlighted that confidence, an integral part of coaches’ and athletes’ perceptions of mental toughness, which emerged from their own applied work with elite rugby league players, is not explicitly or distinctly part of previous hardiness models. Indeed, confidence, self-belief, and self-efficacy have been consistently found to characterize mental toughness in emergent research definitions and conceptualizations, both before and after the work of Clough et al. (e.g., Fourie & Potgieter, 2001; Jones et al., 2002; Thelwell et al., 2005; Middleton et al., 2004).

Coping skills

Findings from Nicholls and Polman (2007) showed a relationship between coping skills with other psychological parameters and athletes’ performance. A study conducted by Ragab (2015) among 18 handball players of Zagazig University using Athletic Coping Skills Inventory—28, Smith, Schutz, Smoll, and Ptacek (1995) has shown that mental toughness and athletics coping skills are closely related to performance success. In another study, the relationships between coping skills and sport performance were taken as the main interest (Christensen & Smith, 2016). Christensen and Smith (2016) defined athletic coping skills as “overt and covert cognitive, affective, and behavioural self-regulatory behaviours that help athletes deal with the demands of the sport environment”. The findings of coping skills and performance for this study supporting the previous studies (Daroglou, 2011; Karamousalidis, Bebetsos, & Laparidis, 2006; Smith & Christensen, 1995) which showed that ACSI subscales and athletic performance have significant relations to each other. Thus, these implicate that mental toughness, coping skills, and performance outcome are inter-related to each other and worth to be studied for the purpose of improving sport development and performance.

Optimism

Another psychological construct that appears to be related to both mental toughness and coping is optimism. In a qualitative study, Gould et al. (2002) reported that Olympic champions report high levels of mental toughness, coping effectiveness, and optimism. Optimism, in this respect, has been defined as “a major determinant of the disjunction between two classes of behaviour: (a) continued striving versus (b) giving up and turning away” (Kelly, 1991; Scheier & Carver, 1985). Researchers became interested in studying optimism because more optimistic individuals exhibit increased effort to achieve goals. Alternatively, less optimistic individuals are more likely to withdraw or disengage attempts at achieving a goal (Carver, Blaney, & Scheier, 1979; Gaudreau & Blondin, 2004; Nes, Segerstrom, & Sephton, 2005). In addition, optimism seems to be a predictor of sport performance. In a study by Norlander and Archer (2002), it was found that optimism was the best predictor of performance in elite male and female cross-country skiers and ski-marksman (16–20 years) and swimmers (16–19 years). Finally, optimism appears to be associated with differences in coping behaviour. In a recent meta-analysis, it was found that more optimistic individuals use more approach coping strategies and fewer avoidance strategies (Solberg & Segerstrom, 2006).

Resilience

Frequently cited within the mental toughness literature is the notion of being able to bounce back from performance setbacks; Jones et al. (2002), and Gucciardi and Gordon (2009) handle failure (Fawcett, 2006) and an apparent ability to overcome adversities with persevering determination (Gucciardi et al., 2008). All of which are attributes synonymous with the concept of dispositional resilience with the main function being described as an encouraging positive adaption despite the presence of risk or adversity (Luthar & Cicchetti, 2000; Masten, 1994; Masten & Reed, 2002). Although distinct, resilience is commonly reported to share a similar conceptual space with mental toughness (Connaughton, 2009). Whilst there are similarities between resilience and mental toughness where both are qualities which refer to an individual’s ability to bounce back following adversity, the former originates predominantly from clinical and psychiatric populations (Rutter, 1985), whereas mental toughness is purported to preside in the context of performance (Jones et al., 2002). Whereas, the greatest distinction is that mental toughness is refer to one ‘thriving’ on the experience and excelling despite adversity, not merely returning to ‘normal’ functioning which resilience would appear contained.

Results

A summary of the papers included in the review is provided in Table 2. While the qualitative methodologies have been an initial method of choice, an increasing number of quantitative approaches have emerged in line with the emergence of various mental toughness inventories designed to assess mental toughness from both sport-specific and sport-general perspectives. Across all the studies, data were gathered from the assessments of 5660 participants (except studies not specified), of which 3316 were male (58.6%), 1018 were female (18.0%), 1326 was not identified (23.4%). The number of participants ranged from 6 to 963 while the mean age of participants ranged from 14.34 to 42.7 years. Throughout the studies, 150 coaches, 4 sport psychologists and 309 others (parents, administrators and engineers) were included. Out of the studies reviewed, 5 adopted sport-specific investigations focused only on one sport (e.g., cricket, soccer, Australian football), whereas 7 investigated mental toughness from a general between-sport perspective across a variety of sports and disciplines.

Study characteristics

The studies included in this review covered a period of 41 years (1978–2019). The studies involved participants from a range of competitive levels, such as school athletes, college athletes, professional athletes, and the general population. In terms of countries distribution, the vast majority of studies were from the European setting. As for sport distribution, there was a varied representation of sports, namely swimming, sprinting, artistic and rhythmic gymnastics, trampolining, middle-distance running, triathlon, golf, netball, boxing, athletics, judo, triathlon, rowing, pentathlon, squash, cricket, soccer, rugby, roller skating, basketball, canoeing, golf, soccer and Australian football. Seven studies involved multiple sports and five studies involved specific sports.

Discussion

For this review, 14 studies of mental toughness emerging definitions and conceptualizations literature to date were identified. The initial interest was focused mainly on the operational definition of mental toughness which was followed by understanding the operational mechanisms underpinning the development of mental toughness and lastly, measurement tools for assessing mental toughness among athletes. While the existence of recurring themes helps in the development of a general understanding of mental toughness and its components, the theoretical development in the early mental toughness literature has been limited by non-empirical studies which appear to be based more on anecdotal, experiential consultations and applied work with elite performers, rather than a result of rigorous systematic programs of research. Recent studies have implemented a more rigorous and systematic approach to understand and examine on mental toughness; however, these have been identified as somewhat problematic and received some criticism for reviews.

Clough et al. (2002) may be criticized of finding a theory (i.e. hardiness) and fitting mental toughness into it without sufficient justification or rationale (Crust, 2007, 2008), and the definition of Jones et al. (2002) could also be seen as limited. Despite the appeal of the definition of Jones et al. (2002) and the comprehensive list of attributes that emerged (Jones et al., 2002, 2007), their definition seems insufficient that only describes the outcomes of mental toughness (i.e., what it enables an athlete to do) and fails to describe and define what exactly mental toughness actually is (Crust, 2007). Likewise, little attempt was made to establish or integrate the findings with established psychological theory, nor was any attempt made to develop a conceptual model with no insight provided into how mental toughness operates or is developed.

Within the literature, most conceptualizations offered were multidimensional in nature and there was an emergent replication of multiple key components which can be broadly classified into various values, attitudes, cognitions and emotions that enabled people to behave in such a way as to achieve their goals in the face of obstacles. The commonalities in these hypothesized psychological characteristics (e.g. self-belief, attention control, motivation, commitment and determination, resilience, and handling pressure) provided some support for the assertion that mental toughness can be defined in a similar manner, irrespective of sport. Nevertheless, the consideration that these studies were not representative of all sports and that studies have also identified sport-specific variances (Gucciardi & Gordon, 2009; Gucciardi et al., 2008; Coulter et al., 2010) suggested that mental toughness may be somewhat contextually driven (Bull et al., 2005).

With a growing understanding of what mental toughness is, and studies supporting the contention that mental toughness could be acquired and developed have resulted in exploring the developing mechanisms of mental toughness (e.g., Jones et al., 2002, 2007; Thelwell et al., 2005). The review identified that the development of mental toughness has been explored from various perspectives such as incorporating the views of performers, coaches, psychologists and parents alike, adopting approaches from within-sport (Bull et al., 2005; Gucciardi et al., 2009). These have resulted in the emergent of common themes, shared experiences and strategies for developing mental toughness.

The environment factor is a prominent influence across the studies reviewed. Bull et al. (2005) reported influences from outside the sporting location affected mental toughness in cricketers. For example, a parents’ attitude towards failure along with the way in which they evaluated performance, would show an effect on the participants’; which in turn may lead to negative associations with criticism, which will not aid progression. It was stated that if the pressure of external entities (such as parents) was to be removed, the athlete would only concentrate on the performance and therefore accomplish more (Bull et al., 2005). Bull et al. (2005) also suggested the need to develop an environment within which players are given maximum opportunity to benefit in terms of character and attitude development as well as tough thinking.

Another prominent theme to be revealed is the role of the coach and how they may facilitate the development of mental toughness. Guccardi et al. (2009) highlighted overarching categories that accounted for the strategies, experiences and mechanisms employed by coaches to develop mental toughness specific to Australian football. These included: early childhood experiences, which played an important role in nurturing a ‘generalized form’ of mental toughness, with football experiences, the coach–athlete relationship, coaching philosophy, the training environment and other specific strategies used to transform this generalized mental toughness into ‘sport-specific forms’. Gucciardi et al. (2009) also stated that the coach’s ability as one of the factors that hinder optimal mental toughness development. The key issues include an unbalanced desire for success overruling individual player development needs, focusing on and over-emphasising player weaknesses, imposing low or unrealistic expectations, and fostering ‘easy’ training environments. These studies have shown that coaches reported an understanding of the term and can admit that it played a vital role in success.

A key question within the field is the contribution of genetic factors over environmental influences. More specifically, there is debate over whether mental toughness is an inherited, personality characteristic (Golby & Sheard, 2006; Horsburgh, Schermer, Veselka, & Vernon, 2009) or is it developed through a socialization process either through specific training (e.g. psychological skills or coach-mediated training) or based on life experiences. Whilst, the reported research supports the view that mental toughness can be developed differentially, it appears that there is an inestimable amount of mental toughness which is based on social experiences and key supportive agents (i.e. parents, coaches, significant others); nevertheless, at least some aspects of mental toughness can be “taught” through specific techniques (Gordon & Sridhar, 2005; Connaughton et al., 2008; Connaughton, Hanton, & Jones, 2010). Jones and colleagues’ (2002) definition provided support for this divided assertion given their acknowledgement that athletes possess inherited characteristics that relate to a “natural” aspect of mental toughness, while proposing that aspects may also be “developed” throughout their careers via learning new skills, experiences of success and failure, with components which must also be “maintained” (Jones et al., 2007).

The review suggests that experiences and environments that individuals are exposed to in the formative years of development are crucial in determining the experience-based aspects of mental toughness. Other aspects developed through the middle years, where performers benefit from others (i.e., expert coaches, elite performers, role models) and finally through the use and development of psychological skills and strategies to enhance and maintain mental toughness are the “taught” components of the construct. What remains to be seen is establishing the most appropriate and effective approaches to assist the development of the aspects absent in individuals when not exposed to such facilitative environments.

Conclusion and future research recommendations

The study of mental toughness has advanced since the adoption of more scientifically rigorous approaches, but there are still a number of limitations and theoretical description that should be considered when interpreting their findings. Although both qualitative (e.g., Bull et al., 2005; Fourie & Potgieter, 2001; Gucciardi et al., 2008; Jones et al., 2002; Middleton et al., 2004; Thelwell et al., 2005) and quantitative approaches (e.g., Clough et al., 2002; 2005; Golby et al., 2007; Gucciardi & Gordon, 2009; Gucciardi et al., 2009; Loehr, 1986; Middleton, 2007; Sheard et al., 2009) have been used to understand mental toughness, there are also differences and agreement in regard to conceptual issues and measurement. Mental toughness appears to be multidimensional and most often associated with unshakeable self-belief, the ability to rebound after failures (resilience), persistence or refusal to quit, coping effectively with adversity and pressure, and retaining concentration in the face of many potential distractions. Most contemporary researchers suggest that an individual’s mental toughness will be determined by both inherited characteristics and by learning, experience, and environments influences (Bull et al., 2005; Gordon & Sridhar, 2005; Jones et al., 2002; Thelwell et al., 2005). Research into the relationship between mental toughness and performance has consistently shown that better performances of both cognitive and motor skills are associated with higher levels of mental toughness (Clough et al., 2002; Crust & Clough, 2005) and those elite athletes have higher mental toughness than lower level performers (Golby et al., 2003; Thomas, Schlinker, & Over, 1996). One of the key advances toward a greater understanding of mental toughness appears to be the development of valid and reliable measurement instruments. Past studies used other psychological variables such as emotions, affections, perceptions or pains as a potential mechanism for psychological mental toughness in competitive sports situations. Therefore, this issue should be considered as the future direction of study because there is still room for further development of potential mechanisms for confirmation.

References

Bartone, P.T., Ursano, R.J., Wright, K.W., & Ingraham, L.H. (1989). The impact of a military air disaster on the health of assistance workers: A prospective study. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease, 177, 317–328.

Brewer, B. W. (2009). Handbook of sports medicine and science, sport psychology. Chichester: John Wiley & Sons Ltd.

Bull, S. J., Albinson, J. G., & Shambrook, C. J. (1996). The mental game plan: Getting psyched for sport. Eastboune: Sports Dynamics.

Bull, S. J., Shambrook, C. J., James, W., & Brooks, J. E. (2005). Towards an understanding of mental toughness in elite English cricketers. Journal of Applied Sport Psychology, 17(3), 209–227. https://doi.org/10.1080/10413200591010085.

Carver, C. S., Blaney, P. H., & Scheier, M. F. (1979). Reassertion and giving up: The interactive role of self directed attention and outcome expectancy. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 37(10), 1859–1870. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.37.10.1859.

Cattell, R. B. (1957). Personality and motivation structure and measurement. Oxford: World Book Co.

Cattell, R. B., Blewett, D. B., & Beloff, J. R. (1955). The inheritance of personality: A multiple variance analysis determination of approximate nature-nurture ratios for primary personality factors in Q data. American Journal of Human Genetics, 7(2), 122–146.

Christensen, D. S., & Smith, R. E. (2016). Psychological coping skills as predictors of collegiate golf performance: Social desirability as a suppressor variable. Sport, Exercise and Performance. Psychology, 5(1), 67–80. https://doi.org/10.1037/spy0000049.

Clough, P., Earle, K., & Sewell, D. (2002). Mental toughness: The concept and its measurement. In I. Cockerill (Ed.), Solutions in sport psycholology (pp. 32–43). London: Thomson Learning.

Connaughton, D., & Hanton, S. (2009). Mental toughness in sport: Conceptual and practical issues. In S. Mellalieu & S. Hanton (Eds.), Advances in applied sport psychology: A review (pp. 317–346). London: Routledge.

Connaughton, D., Hanton, S., & Jones, G. (2010). The development and maintenance of mental toughness in the world’s best performers. The Sport Psychologist, 24(2), 168–193. https://doi.org/10.1123/tsp.24.2.168.

Connaughton, D., Wadey, R., Hanton, S., & Jones, G. (2008). The development and maintenance of mental toughness: Perceptions of elite performers. Journal of Sports Sciences, 26(1), 83–95. https://doi.org/10.1080/02640410701310958.

Connor, K. M. & Davidson, J. R. T. (2003). Development of a new resilience scale: The Connor-Davidson Resilience Scale (CD-RISC). Depression and Anxiety, 18, 76–82. https://doi.org/10.1080/10705500802222972.

Coulter, T. J., Mallett, C. J., & Gucciardi, D. F. (2010). Understanding mental toughness in Australian soccer: Perceptions of players, parents, and coaches. Journal of Sports Sciences, 28(7), 699–716. https://doi.org/10.1080/02640411003734085.

Crust, L. (2007). Mental toughness in sport: A review. International Journal of Sport and Exercise Psychology, 5(3), 270–290.

Crust, L. (2008). A review and conceptual re-examination of mental toughness: Implications for future researchers. Personality and Individual Differences, 45, 576–583. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2008.07.005.

Crust, L., & Clough, P. J. (2005). Relationship between mental toughness and physical endurance. Perceptual and Motor Skills, 100(1), 192–194. https://doi.org/10.2466/pms.100.1.192–194.

Daroglou, G. (2011). Coping skills and self-efficacy as predictors of gymnastic performance. The Sport Journal,, 14(1), 1–6.

Dennis, P. W. (1978). Mental toughness and performance success and failure. Perceptual and Motor Skills, 46(2), 385–386. https://doi.org/10.2466/pms.1978.46.2.385.

Fawcett, T. (2006). An investigation into the perceptions of mental toughness of adventurers/explorers, elite athletes and elite coaches. Doctoral dissertation, University of Northumbria at Newcastle.

Fourie, S., & Potgieter, J. R. (2001). The nature of mental toughness in sport. South African Journal for Research in Sport, Physical Education and Recreation,, 23(2), 63–72. https://doi.org/10.4314/sajrs.v23i2.25860.

Gaudreau, P., & Blondin, J. P. (2004). Differential associations of dispositional optimism and pessimism with coping, goal attainment, and emotional adjustment during sport competition. International Journal of Stress Management, 11(3), 245–269. https://doi.org/10.1037/1072-5245.11.3.245.

Gibson, A. (1998). Mental toughness. New York: Vantage Press.

Golby, J., & Sheard, M. (2004). Mental toughness and hardiness at different levels of rugby league. Personality and Individual Differences, 37, 933–942. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2003.10.015.

Golby, J., & Sheard, M. (2006). The relationship between genotype and positive psychological development in national-level swimmers. European Psychologist, 11(2), 143–148. https://doi.org/10.1027/1016-9040.11.2.143.

Golby, J., Sheard, M., & Lavallee, D. (2003). A cognitive-behavioural analysis of mental toughness in national rugby league football teams. Perceptual and Motor Skills, 96, 455–462.

Golby, J., Sheard, M., & Van Wersch, A. (2007). Evaluating the factor structure of the psychological performance inventory. Perceptual and Motor Skills, 105(1), 309–325. https://doi.org/10.2466/pms.105.1.309-325.

Gordon, S., & Sridhar, S. (2005). Identification and development of mental toughness. ISSP 11th World Congress of Sport Psychology, Sydney, Australia.

Gould, D., Dieffenbach, K., & Moffett, A. (2002). Psychological characteristics and their development in Olympic champions. Journal of Applied Sport Psychology, 14(3), 172–204. https://doi.org/10.1080/10413200290103482.

Gould, D., Hodge, K., Peterson, K., & Petlichkoff, L. (1987). Psychological foundations of coaching: Similarities and differences among intercollegiate wrestling coaches. The Sport Psychologist, 1(4), 293–308. https://doi.org/10.1123/tsp.1.4.293.

Gucciardi, D. F. (2011). The relationship between developmental experiences and mental toughness in adolescent cricketers. Journal of Sport and Exercise Psychology, 33(3), 370–393. https://doi.org/10.1123/jsep.33.3.370.

Gucciardi, D. F., & Gordon, S. (2009). Development and preliminary validation of the Cricket Mental Toughness Inventory (CMTI). Journal of Sports Sciences, 27(12), 1293–1310. https://doi.org/10.1080/02640410903242306.

Gucciardi, D. F., Gordon, S., & Dimmock, J. A. (2008). Towards an understanding of mental toughness in Australian football. Journal of Applied Sport Psychology, 20(3), 261–281. https://doi.org/10.1080/10413200801998556.

Gucciardi, D. F., Gordon, S., & Dimmock, J. A. (2009). Development and preliminary validation of a mental toughness inventory for Australian football. Psychology of Sport Exercise, 10(1), 201–209. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychsport.2008.07.011.

Horsburgh, V. A., Schermer, J. A., Veselka, L., & Vernon, P. A. (2009). A behavioural genetic study of mental toughness and personality. Personality and Individual Differences, 46(2), 100–105. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2008.09.009.

Jackson, S. A., & Eklund, R. C. (2002). Assessing flow in physical activity: The flow state scale-2 and dispositional flow scale-2. Journal of Sport & Exercise Psychology, 24, 133–150.

Jones, G., Hanton, S., & Connaughton, D. (2002). What is this thing called mental toughness? An investigation of elite sport performers. Journal of Applied Sport Psychology, 14(3), 205–218. https://doi.org/10.1080/10413200290103509.

Jones, G., Hanton, S., & Connaughton, D. (2007). A framework of mental toughness in the world’s best performers. The Sport Psychologist, 21(2), 243–264. https://doi.org/10.1123/tsp.21.2.243.

Karamousalidis, G., Bebetsos, E., & Laparidis, G. (2006). Psychological skills of Greek basketball players. Inquiries in Sport & Physical Education, 4(3), 442–448.

Kelly, G. A. (1955). The psychology of personal constructs. New York: WW Norton and Company.

Kelly, G. A. (1991). A theory of personality. The psychology of personal constructs, Vol. 1. New York: WW Norton and Company.

Kobasa, S. C. (1979). Stressful life events, personality, and health: An inquiry into hardiness. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 37(1), 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.37.1.1.

Kobasa, S. C., Maddi, S. R., & Kahn, S. (1982). Hardiness and health: A prospective study. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 42(1), 168–177. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.42.1.168.

Kroll, W. (1967). Sixteen personality factor profiles of collegiate wrestlers. Research Quarterly. American Association for Health, Physical Education and Recreation, 38(1), 49–57. https://doi.org/10.1080/10671188.1967.10614802.

Kuan, G., & Roy, J. (2007). Goal profiles, mental toughness and its influence on performance outcomes among Wushu athletes. Journal of Sports Science and Medicine, 6(CSSI-2), 28–33.

Lee, K., Shin, D. S., Han, M., & Lee, E. (1994). Developing the norm of Korean table tennis players’ mental toughness. Korean Journal of Sport Science, 6, 103–120.

Loehr, J. E. (1982). Athletic excellence: Mental toughness training for sports. New York: Plume.

Loehr, J. E. (1986). Mental toughness training for sports: Achieving athletic excellence. Lexington: Stephen Greene.

Loehr, J. E. (1995). The new toughness training for sports: Mental, emotional, and physical conditioning from one of the world’s premier sports psychologists. New York: Plume.

Luthar, S. S., & Cicchetti, D. (2000). The construct of resilience: Implications for interventions and social policies. Development and Psychopathology, 12(4), 857–885. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0954579400004156.

Masten, A. S. (1994). Resilience in individual development: Successful adaptation despite risk and adversity: Challenges and prospects. In M. Wang & E. Gordon (Eds.), Educational resilience in inner city America: Challenges and prospects (pp. 3–25). Hillsdale: Lawrence Erlbaum.

Masten, A. S., & Reed, M. G. (2002). Resilience in development. In S. J. Lopez & C. R. Snyder (Eds.), The Oxford Handbook of positive psychology (pp. 74–88). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Middleton, S. C., Marsh, H. W., Martin, A. J., Richards, G. E., Savis, J., Perry, C., & Brown, R. (2004). The Psychological Performance Inventory: Is the mental toughness test tough enough? International Journal of Sport Psychology, 35(2), 91–108.

Middleton, S. C., Marsh, H. W., Martin, A. J., Richards, G. E., & Perry, C. (2005). Developing a test for mental toughness: The Mental Toughness Inventory (MTI). In Australian Association for Research in Education 2005 conference papers.

Middleton, S. C., Martin, A. J., & Marsh, H. W. (2011). Development and validation of the Mental Toughness Inventory (MTI): A construct validation approach. In D. F. Gucciardi & S. Gordon (Eds.), Mental toughness in sport: Developments in theory and research (pp. 91–107). London: Routledge.

Middleton, S.C. (2007). Mental Toughness: Conceptualisation and Measurement. Doctoral dissertation, School of Psychology, University of Western Sydney.

Moher, D., Shamseer, L., Clarke, M., Ghersi, D., Liberati, A., Petticrew, M., & Stewart, L. A. (2015). Preferred reporting items for systematic review and meta-analysis protocols (PRISMA-P) 2015 statement. Systematic Reviews, 4(1), 1. https://doi.org/10.1186/2046-4053-4-1.

Nes, L. S., Segerstrom, S. C., & Sephton, S. E. (2005). Engagement and arousal: Optimism’s effects during a brief stressor. Personal and Social Psychology Bulletin, 31(1), 111–120. https://doi.org/10.1177/0146167204271319.

Nicholls, A., & Polman, R. (2007). Coping in sport: A systematic review. Journal of Sports Sciences, 25(1), 11–31. https://doi.org/10.1080/02640410600630654.

Norlander, T., & Archer, T. (2002). Predicting performance in ski and swim championships: Effectiveness of mood, perceived exertion, and dispositional optimism. Perceptual and Motor Skills, 94(1), 153–164. https://doi.org/10.2466/pms.2002.94.1.153.

Raedeke, T. D., & Smith, A. L. (2001). Development and preliminary validation of an athlete burnout measure. Journal of Sport and Exercise Psychology, 23, 281–306.

Ragab, M. (2015). The effects of mental toughness training on athletic coping skills and shooting effectiveness for national handball players. Science, Movement and Health, 15(2), 431–435.

Reynolds, W. M. (1982). Development of reliable and valid short forms of the marlowe-crowne social desirability scale. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 38, 119–125. https://doi.org/10.1002/1097-4679(198201)38

Rutter, M. (1985). Resilience in the face of adversity: Protective factors and resistance to psychiatric disorder. British Journal of Psychiatry, 147(6), 598–611. https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.147.6.598.

Scheier, M. F., & Carver, C. S. (1985). Optimism, coping, and health: Assessment and implications of generalized outcome expectancies. Health Psychology, 4(3), 219–247. https://doi.org/10.1037/0278-6133.4.3.219.

Sheard, M. (2009). A cross-national analysis of mental toughness and hardiness in elite university rugby league teams. Perceptual and Motor Skills, 109(1), 213–223. https://doi.org/10.2466/pms.109.1.213–223.

Sheard, M. (2012). Mental toughness: The mindset behind sporting achievement. London: Routledge.

Sheard, M., Golby, J., & Van Wersch, A. (2009). Progress toward construct validation of the Sports Mental Toughness Questionnaire (SMTQ). European Journal of Psychological Assessment, 25(3), 186–193. https://doi.org/10.1027/1015-5759.25.3.186.

Smith, R. E., & Christensen, D. S. (1995). Psychological skills as predictors of performance and survival in professional baseball. Journal of Sport and Exercise Psychology, 17(4), 399–415. https://doi.org/10.1123/jsep.17.4.399.

Smith, R. E., Schutz, R. W., Smoll, F. L., & Ptacek, J. T. (1995). Development and validation of a multidimensional measure of sport-specific psychological skills: The Athletic Coping Skills Inventory-28. Journal of Sport and Exercise Psychology, 17(4), 379–398. https://doi.org/10.1123/jsep.17.4.379.

Solberg, N. L., & Segerstrom, S. C. (2006). Dispositional optimism and coping: A meta-analytic review. Personality and Social Psychology Review, 10(3), 235–251. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15327957pspr1003_3.

Tapp, J. (1991). Mental toughness. Referee, 16, 44–48.

Thelwell, R., Weston, N., & Greenlees, I. (2005). Defining and understanding mental toughness within soccer. Journal of Applied Sport Psychology, 17(4), 326–332. https://doi.org/10.1080/10413200500313636.

Thomas, P. R., Schlinker, P. J., & Over, R. (1996). Psychological and psychomotor skills associated with prowess at ten-pin bowling. Journal of Sports Sciences, 14(3), 255–268. https://doi.org/10.1080/02640419608727709.

Tutko, T. A., & Richards, J. W. (1971). Psychology of coaching. Boston: Allyn and Bacon.

Tutko, T. A., & Richards, J. W. (1972). Coach’s practical guide to athletic motivation. Boston: Allyn and Bacon.

Weinberg, R. S., & Gould, D. (2003). Foundations of sport and exercise psychology. Champaign: Human Kinetics.

Werner, A. C., & Gottheil, E. (1966). Personality development and participation in college athletics. Research Quartely. American Association for Health, Physical Education and Recreation, 37(1), 126–131. https://doi.org/10.1080/10671188.1966.10614745.

Funding

The present study was supported by the Research University’s Individual Grant (USM-RUI) from Universiti Sains Malaysia (1001/PPSP/812149).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors listed have made a substantial, direct and intellectual contribution to the work, and approved it for publication.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

L.G. Chen, G. Kuan, C.N. Siong and H.A. Hashim declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

The study was carried out in accordance with the recommendations from the Universiti Sains Malaysia’s Human Research Ethics Committee (USM/JEPeM/16020085).

Rights and permissions

Open Access. This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Liew, G.C., Kuan, G., Chin, N.S. et al. Mental toughness in sport. Ger J Exerc Sport Res 49, 381–394 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12662-019-00603-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12662-019-00603-3