Abstract

Background

Excess sugar consumption has been linked to numerous negative health outcomes, such as obesity and type II diabetes. Reducing sugar-sweetened beverage (SSB) consumption may reduce sugar intake and thus improve health. The aim of the study was to test the impact of the potentially different rewarding nature of water or diet drinks as replacements for SSB, using a habit and implementation intention–based intervention.

Method

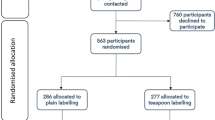

An online randomised, two-arm parallel design was used. One hundred and fifty-eight participants (mainly from the UK and USA) who regularly consumed SSBs (Mage = 31.5, 51% female) were advised to create implementation intentions to substitute their SSB with either water or a diet drink. Measures of SSB consumption, habit strength and hedonic liking were taken at baseline and at 2 months. Water or diet drink consumption was only measured at 2 months.

Results

There was a large and significant reduction in SSB consumption and self-reported SSB habits for both the water and diet drink groups, but no difference between groups. There were no differences in hedonic liking for the alternative drink, alternative drink consumption and alternative drink habit between the two groups. Reduction in SSB hedonic liking was associated with reduced SSB consumption and habit.

Conclusion

This study demonstrates that an implementation intention–based intervention achieved substantial reductions in SSB consumption and habits. It also indicates that hedonic liking for SSBs and alternative drinks are associated with changes in consumption behaviour. Substituting SSBs with water or diet drinks was equally as effective in reducing SSB consumption.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

The frequency, hedonic liking and habit questions for the SSBs were automatically populated with the type of drink they reported drinking most frequently. For the alternative drinks, the question text specified “water”/“artificially sweetened drinks” but the sections were preceded by a statement saying that: “Artificially-sweetened Drinks” refers to your preferred artificially-sweetened drink / “Water” refers to your preferred type of water.

References

Imamura F, et al. Consumption of sugar sweetened beverages, artificially sweetened beverages, and fruit juice and incidence of type 2 diabetes: systematic review, meta-analysis, and estimation of population attributable fraction. Bmj. 2015;351:h3576.

Rayner M, Scarborough P, A. Briggs Public Health England’s report on sugar reduction. 2015;351(nov19 11):h6095–h6095.

Dobbs R, et al. Overcoming obesity: an initial economic analysis. McKinsey & Company; 2014. p. 1–106. www.mckinsey.com/mgi.

National Center for Health Statistics. Health, United States, 2014: with special feature on adults aged 55–64. 2015. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/hus/hus14.pdf.

Organization, W.H. Guideline: sugars intake for adults and children. World Health Organization; 2015.

Leary KS, Nowak AJ. Prevention of dental disease, in Pediatric Dentistry. Elsevier; 2019. p. 455–460.

Buttris J. Why 5%? An explanation of SACN’s recommendations about sugars and health: Public Health England. 2015. Available at : https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/sacns-sugars-and-health-330recommendations-why-5.

Judah G, Gardner B, Kenward MG, DeStavola B, Aunger R. Exploratory study of the impact of perceived reward on habit formation. BMC Psychol. 2018;6(1):62.

Allom V, Mullan B, Sebastian J. Closing the intention–behaviour gap for sunscreen use and sun protection behaviours. Psychol Health. 2013;28(5):477–94.

Allom V, Mullan B, Cowie E, Hamilton K. Physical activity and transitioning to college: the importance of intentions and habits. Am J Health Behav. 2016;40(2):280–90.

Gardner B, Phillips LA, Judah G. Habitual instigation and habitual execution: definition, measurement, and effects on behaviour frequency. Br J Health Psychol. 2016;21(3):613–30.

Allom V, Mullan B. Maintaining healthy eating behaviour: experiences and perceptions of young adults. Nutr Food Sci. 2014;44:156–67.

Kothe EJ, Sainsbury K, Smith L, Mullan BA. Explaining the intention–behaviour gap in gluten-free diet adherence: the moderating roles of habit and perceived behavioural control. J Health Psychol. 2015;20(5):580–91.

Moran A, Mullan B. (In Press). Exploring temporal self-regulation theory to predict sugar-sweetened beverage consumption. Psychology & Health.

McGowan L, Cooke LJ, Gardner B, Beeken RJ, Croker H, Wardle J. Healthy feeding habits: efficacy results from a cluster-randomized, controlled exploratory trial of a novel, habit-based intervention with parents. Am J Clin Nutr. 2013;98(3):769–77.

Verplanken B, Orbell S. Reflections on past behavior: a self-report index of habit strength 1. J Appl Soc Psychol. 2003;33(6):1313–30.

Murray KS, Mullan B. Can temporal self-regulation theory and ‘sensitivity to reward’predict binge drinking amongst university students in Australia? Addict Behav. 2019;99:106069.

de Bruijn G-J, van den Putte B. Adolescent soft drink consumption, television viewing and habit strength. Investigating clustering effects in the theory of planned behaviour. Appetite. 2009;53(1):66–75.

Orbell S, Verplanken B. The automatic component of habit in health behavior: habit as cue-contingent automaticity. Health Psychol. 2010;29(4):374–83.

Wood W, Neal DT. A new look at habits and the habit-goal interface. Psychol Rev. 2007;114(4):843–63.

Jeffery RW, Epstein LH, Wilson GT, Drewnowski A, Stunkard AJ, Wing RR. Long-term maintenance of weight loss: current status. Health Psychol. 2000;19(1S):5–16.

McCaul EJ, Donaldson GA Jr, Coladarci T, Davis WE. Consequences of dropping out of school: findings from high school and beyond. J Educ Res. 1992;85(4):198–207.

Kwasnicka D, Dombrowski SU, White M, Sniehotta F. Theoretical explanations for maintenance of behaviour change: a systematic review of behaviour theories. Health Psychol Rev. 2016;10(3):277–96.

Galla BM, Duckworth AL. More than resisting temptation: beneficial habits mediate the relationship between self-control and positive life outcomes. J Pers Soc Psychol. 2015;109(3):508–25.

Holland RW, Aarts H, Langendam D. Breaking and creating habits on the working floor: a field-experiment on the power of implementation intentions. J Exp Soc Psychol. 2006;42(6):776–83.

Lin P-Y, Wood W, Monterosso J. Healthy eating habits protect against temptations. Appetite. 2016;103:432–40.

Rees JH, Bamberg S, Jäger A, Victor L, Bergmeyer M, Friese M. Breaking the habit: on the highly habitualized nature of meat consumption and implementation intentions as one effective way of reducing it. Basic Appl Soc Psychol. 2018;40(3):136–47.

Verplanken B, Faes S. Good intentions, bad habits, and effects of forming implementation intentions on healthy eating. Eur J Soc Psychol. 1999;29(5–6):591–604.

Prestwich A, et al. Implementation intentions, in predicting and changing health behaviour: research and practice with social cognition models. In: Conner M, Norman P, editors. . Buckingham: Open University Press; 2015.

Arbour KP, Martin Ginis KA. A randomised controlled trial of the effects of implementation intentions on women’s walking behaviour. Psychol Health. 2009;24(1):49–65.

Adriaanse MA, de Ridder DT, de Wit JB. Finding the critical cue: implementation intentions to change one’s diet work best when tailored to personally relevant reasons for unhealthy eating. Personal Soc Psychol Bull. 2009;35(1):60–71.

Armitage CJ. A volitional help sheet to encourage smoking cessation: a randomized exploratory trial. Health Psychol. 2008;27(5):557–66.

Mairs L, Mullan B. Self-monitoring vs. implementation intentions: a comparison of behaviour change techniques to improve sleep hygiene and sleep outcomes in students. Int J Behav Med. 2015;22(5):635–44.

Schüz B, Wiedemann AU, Mallach N, Scholz U. Effects of a short behavioural intervention for dental flossing: randomized-controlled trial on planning when, where and how. J Clin Periodontol. 2009;36(6):498–505.

Sheeran P, et al. Implementation intentions and health behaviour. 2005.

Aarts H, Dijksterhuis A. Habits as knowledge structures: automaticity in goal-directed behavior. J Pers Soc Psychol. 2000;78(1):53–63.

Mullan B, Novoradovskaya E. Habit mechanisms and behavioural complexity. In: The psychology of habit. Springer; 2018. p. 71–90.

Adriaanse MA, Gollwitzer PM, de Ridder DTD, de Wit JBF, Kroese FM. Breaking habits with implementation intentions: a test of underlying processes. Personal Soc Psychol Bull. 2011;37(4):502–13.

Webb TL, Sheeran P, Luszczynska A. Planning to break unwanted habits: habit strength moderates implementation intention effects on behaviour change. Br J Soc Psychol. 2009;48(3):507–23.

Ames SL, Wurpts IC, Pike JR, MacKinnon DP, Reynolds KR, Stacy AW. Self-regulation interventions to reduce consumption of sugar-sweetened beverages in adolescents. Appetite. 2016;105:652–62.

Adriaanse MA, Vinkers CDW, de Ridder DTD, Hox JJ, de Wit JBF. Do implementation intentions help to eat a healthy diet? A systematic review and meta-analysis of the empirical evidence. Appetite. 2011;56(1):183–93.

Wiedemann AU, Lippke S, Reuter T, Ziegelmann JP, Schüz B. The more the better? The number of plans predicts health behaviour change. Appl Psychol: Health Well-Being. 2011;3(1):87–106.

Verhoeven AA, et al. Less is more: the effect of multiple implementation intentions targeting unhealthy snacking habits. Eur J Soc Psychol. 2013;43(5):344–54.

Webb TL, Sheeran P. Does changing behavioral intentions engender behavior change? A meta-analysis of the experimental evidence. Psychol Bull. 2006;132(2):249–68.

de Wit S, Dickinson A. Associative theories of goal-directed behaviour: a case for animal–human translational models. Psychol Res PRPF. 2009;73(4):463–76.

Lally P, Gardner B. Promoting habit formation. Health Psychology Review. 2013;7(sup1):S137–58.

Naughton P, McCarthy M, McCarthy S. Acting to self-regulate unhealthy eating habits. An investigation into the effects of habit, hedonic hunger and self-regulation on sugar consumption from confectionery foods. Food Qual Prefer. 2015;46:173–83.

Verhoeven AA, et al. The power of habits: unhealthy snacking behaviour is primarily predicted by habit strength. Br J Health Psychol. 2012;17(4):758–70.

Collins A, Mullan B. An extension of the theory of planned behavior to predict immediate hedonic behaviors and distal benefit behaviors. Food Qual Prefer. 2011;22(7):638–46.

Silva MN, et al. Exercise autonomous motivation predicts 3-yr weight loss in women. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2011;43(4):728–37.

Wiedemann AU, Gardner B, Knoll N, Burkert S. Intrinsic rewards, fruit and vegetable consumption, and habit strength: a three-wave study testing the associative-cybernetic model. Appl Psychol: Health Well-Being. 2014;6(1):119–34.

Ebbeling CB, Feldman HA, Osganian SK, Chomitz VR, Ellenbogen SJ, Ludwig DS. Effects of decreasing sugar-sweetened beverage consumption on body weight in adolescents: a randomized, controlled pilot study. Pediatrics. 2006;117(3):673–80.

Hu FB. Resolved: there is sufficient scientific evidence that decreasing sugar-sweetened beverage consumption will reduce the prevalence of obesity and obesity-related diseases. Obes Rev. 2013;14(8):606–19.

Zheng M, Allman-Farinelli M, Heitmann BL, Rangan A. Substitution of sugar-sweetened beverages with other beverage alternatives: a review of long-term health outcomes. J Acad Nutr Diet. 2015;115(5):767–79.

Ouellette JA, Wood W. Habit and intention in everyday life: the multiple processes by which past behavior predicts future behavior. Psychol Bull. 1998;124(1):54–74.

Lewis-Esquerre JM, Colby SM, Tevyaw TO’L, Eaton CA, Kahler CW, Monti PM. Validation of the timeline follow-back in the assessment of adolescent smoking. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2005;79(1):33–43.

Sobell LC, Sobell MB. Timeline follow-back, in Measuring alcohol consumption. Springer; 1992. p. 41–72.

Gardner B, Abraham C, Lally P, de Bruijn GJ. Towards parsimony in habit measurement: testing the convergent and predictive validity of an automaticity subscale of the Self-Report Habit Index. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2012;9(1):102.

Waterman AS, Schwartz SJ, Conti R. The implications of two conceptions of happiness (hedonic enjoyment and eudaimonia) for the understanding of intrinsic motivation. J Happiness Stud. 2008;9(1):41–79.

Neumark-Sztainer D, Wall M, Perry C, Story M. Correlates of fruit and vegetable intake among adolescents: findings from Project EAT. Prev Med. 2003;37(3):198–208.

Tobias R. Changing behavior by memory aids: a social psychological model of prospective memory and habit development tested with dynamic field data. Psychol Rev. 2009;116(2):408–38.

Michie S, Richardson M, Johnston M, Abraham C, Francis J, Hardeman W, et al. The behavior change technique taxonomy (v1) of 93 hierarchically clustered techniques: building an international consensus for the reporting of behavior change interventions. Ann Behav Med. 2013;46(1):81–95.

Tabachnick B, Fidell L. Using multivariate Statistics. 5th ed. Boston: Pearson International Edition; 2006.

Zoellner JM, Hedrick VE, You W, Chen Y, Davy BM, Porter KJ, et al. Effects of a behavioral and health literacy intervention to reduce sugar-sweetened beverages: a randomized-controlled trial. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2016;13(1):38.

Wood W, Neal DT. The habitual consumer. J Consum Psychol. 2009;19(4):579–92.

Bartle T, Mullan B, Novoradovskaya E, Allom V, Hasking P. The role of choice in eating behaviours. Br Food J. 2019;121:2696–707.

Ng JY, et al. Self-determination theory applied to health contexts: a meta-analysis. Perspect Psychol Sci. 2012;7(4):325–40.

Singh GM, et al. Global, regional, and national consumption of sugar-sweetened beverages, fruit juices, and milk: a systematic assessment of beverage intake in 187 countries. PLoS One. 2015;10(8).

Office For National Statistics. Employment rate. Available at: http://www.ons.gov.uk/employmentandlabourmarket/peopleinwork/employmentandemployeetypes/timeseries/lf24/lms [11/05/2020].

Bureau, U.S.C. 2020 [cited 2020 11/05/2020]; Available from: https://www.census.gov/quickfacts/fact/table/US/PST045218.

Prestwich A, Perugini M, Hurling R. Can implementation intentions and text messages promote brisk walking? A randomized trial. Health Psychol. 2010;29(1):40–9.

Sniehotta FF, Presseau J. The habitual use of the Self-report Habit Index. Ann Behav Med. 2012;43(1):139–40.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic Supplementary Material

ESM 1

(DOCX 8737 kb)

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Judah, G., Mullan, B., Yee, M. et al. A Habit-Based Randomised Controlled Trial to Reduce Sugar-Sweetened Beverage Consumption: the Impact of the Substituted Beverage on Behaviour and Habit Strength. Int.J. Behav. Med. 27, 623–635 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12529-020-09906-4

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12529-020-09906-4