Abstract

The interdisciplinary study of Egyptian- and Greek-style pottery found in the Nile Delta aims to test and expand the potential of different scientific methods to identify regional variation and cultural traditions in ceramic fabrics from a relatively uniform geological setting. Neutron activation analysis (NAA), polarised light microscopy and SEM-EDX analyses were used to examine raw materials and technological tradition in 32 objects, including 15 previously partly analysed pieces, chosen to test the hypotheses of (a) chemical and (b) technological variation between regionally and/or culturally distinct pottery traditions. Several hundred published NAA data from other studies of Egyptian ceramics were re-assessed within this work. Our NAA results confirmed that all 28 objects analysed originated in Egypt, but could not distinguish production centres. Polarised light microscopy clarified the chaîne opératoire and highlighted Greek and Egyptian technological traditions and regional variations in the production of macroscopically similar ware (e.g. Black Ware). SEM-EDX was essential in distinguishing different recipes used for slips, suggesting patterns of technological transfer and adaptation.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

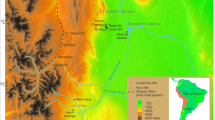

Kaolinite clays deriving from Nubian sandstone were deposited by the Tethys Sea in the Lower Cretaceous, principally at Aswan and in the western desert oases of Kharga, and Dakhla. Marl clays, originating from shale and limestone, are found along the Nile valley between Esna and Cairo and in the western oases, deposited between the Upper Cretaceous and Miocene. Alluvial ‘Nile silt’ or ‘silt’ clay is the youngest product, deposited by the Nile along its valley and delta, including far away from present course river branches, between the Upper Pleistocene and the present. See Bourriau and Nordström 1993, 157–161.

A core of 12 samples for both NAA and petrographic/SEM-EDX analysis was chosen at the start of this phase of the project, guided by archaeological and macroscopic fabric assessment. Only some of the objects previously analysed by NAA were available for thin sectioning, but additional pieces representing specific archaeological groups were selected for petrographic and SEM-EDX so as to expand the scope for technological examination. This selection process explains why there is no complete overlap between the sample groups for each method.

The likely findspot of Tanis is inferred from the date and circumstances of the object’s acquisition by the British Museum, researched by Jeffery Spencer.

In pattern EgB given in Table 2, the Cr (11.4% down: 154.) and Yb (5.7% up: 3.44) values were not yet corrected as in group QanN and as in Fig. 3b. This correction of the Berkeley results was introduced by Strange et al. (1995, 186). The 49 samples of group EgB and their best relative fit factor with respect to EgB are the following: Egy1 (1.18), Egy2 (0.95), Egy5 (0.92), Egy6 (1.00), Egy11 (0.95), Egy17 (1.11), Egy18 (0.97), Egy21 (0.99), Egy23 (1.00), Egy24 (0.94), Egy26 (1.00), Egy30 (1.02), Egy32 (0.97), Egy35 (1.06), Egy36 (0.93), Egy37 (0.97), Egy40 (0.99), Egy41 (1.03), Egy52 (0.94), Egy53 (0.91), Egy54 (0.90), Egy55 (1.00), Egy58 (0.98), Egy59 (0.96), Egy60 (1.04), Egy62 (0.99), Egy63 (0.96), Egy64 (0.99), Egy70 (1.02), Egy80 (0.95), Egy127 (1.02), Egy129 (0.94), Egy131 (0.91), Egy132 (0.99), Egy133 (0.95), Egy134 (0.96), Egy135 (1.01), Egy164 (1.12), Egy165 (0.94), Egy166 (1.05), Egy174 (0.96), Egy178 (1.00), Egy217 (1.20), Egy220 (0.96), Egy324 (0.93), Egy331 (1.15), Egy342 (0.96), Egy365 (1.12), Egy382 (1.02)

The seven groups and their best relative fit factor with respect to the average values are as follows: MEMPHIS-34 (1.01), AMARNA-3 (0.97), DAKHLE-2 (1.00), BENI HASAN-3 (0.98), GEBEL ADDA-13 (0.95), GEBEL-ADDA-1 (0.97), LUXOR-3 (1.08). The Ti value of group MEMPHIS has been corrected; see this same pattern repeated in Table 2 with the correct Ti value. Also, a 10 has been added to the certainly erroneously given single-digit uncertainties for V before calculating the average values of this Nile mud group using all elements given except Ca, Na and Cl. These elements are known to scatter widely probably due to often occurring lime and salt contaminations and, if considered in grouping, will often result in wrongly formed groups.

The 46 samples taken from the PhD of Bellido, 1995, forming group ESIL and their best relative fit factors with respect to this group are as follows: EGMA06 (0.93), EGNC09 (1.16), EGNC62A (0.98), EGNBA5 (0.89), EGNBA8 (1.00), EGNB37 (0.96), EGNB43 (1.17), EGNB01 (0.98), EGNBA0 (1.10), EGNBA1 (1.05), EGNBA2 (1.02), EGNB24 (1.00), EGNB25 (0.97), EGNB26 (0.94), EGNB27 (1.03), EGNB29 (1.02), EGNB30 (0.95), EGNB31 (1.00), EGNB32 (0.98), EGNB44 (0.87), EGNB45 (0.92), EGNB46 (1.06), EGNB48 (0.93), EGNB63M (0.98), EGNBA3 (0.88), EGNB39 (0.87), EGN 35 (1.36), 36 (1.15), EGK12M (0.97), EGK51M (0.91), EGK56M (0.90), EGB103 (1.02), EGB104 (1.07), EGB105 (1.07), EGB106 (1.07), EGB107 (0.94), EGB108 (1.09), EGB109 (1.11), EGB110 (1.09), EGB111 (1.01), EGB131 (0.90), EGB132 (0.95), EGB134 (0.94), EGB137 (0.96), EGB138 (0.95), EGMM50 (0.86).

It seems that the Ce values of the data had already been changed for the Bourriau et al. (2006) publication (Berkeley calibration?). In the data archives we used here, the Ce value seems to be the older, higher one.

Fine inclusions of epidote are occasionally present in other samples as well, but not as coarse grains.

No biotite was present in the Memphis fabric published by Bourriau et al. (2000b), colour plate 3b.

Without analysing samples of all soil types available to ancient craftsmen at each production centre, it is difficult to exclude the alternative interpretation, that the figurines were made from a particularly fine homogeneous raw material, without additional processing, but this is considered less likely.

Levigated alluvial fabrics have also been observed in earlier pottery at Memphis: Bourriau et al. (2000b, 31), fabric group G2 (Nile B1).

With the exception of the Tanis sample

Analyses of the red slips on Old Kingdom pottery from Saqqara have noted the likely addition of hematite, soot and organic binder: Rzeuska (2006, 567)

Seifert (2004, 41, 46 Fig. 25); on average, they are 0.005 mm thick.

References

Al-Dayel OAF (1995) Characterisation of ancient Egyptian ceramics. University of Manchester, PhD Dissertation

Allen RO, Hamroush H, Hoffman MA (1989) Archaeological implications of differences in the composition of Nile sediments. In: Allen RO (ed) Archaeological chemistry IV. American Chemical Society, Washington DC, pp 33–56. https://doi.org/10.1021/ba-1988-0220.ch003

Arnold D, Bourriau J (1993) An introduction to ancient Egyptian pottery, SDAIK 17. Philipp von Zabern, Mainz am Rhein

Artzy M, Asaro F (1979) Origin of Tell El-Yahudiyah Ware found in Cyprus. Reports of the Department of Antiquities of Cyprus 1979:135–150

Bailey DM (2008) Catalogue of the terracottas in the British Museum. British Museum Press, London, IV. Ptolemaic and Roman terracottas from Egypt

Beier T, Mommsen H (1994a) Modified Mahalanobis filters for grouping pottery by chemical composition. Archaeometry 36(2):287–306. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1475-4754.1994.tb00971.x

Beier T, Mommsen H (1994b) A method for classifying multidimensional data with respect to uncertainties of measurement and its application to archaeometry. Naturwissenschaften 91:546–548

Bellido Bernedo AV (1989) Neutron activation analysis of ancient Egyptian pottery. University of Manchester, PhD Dissertation

Berg I (2013) The potter’s wheel in Mycenaean Greece: a re-assessment. In: Graziadio G, Guglielmino R, Lenuzza V, Vitale S (eds) Φιλικη Συναυλια. Studies in Mediterranean archaeology for Mario Benzi. BAR International Series 2460. Archaeopress, Oxford, pp 113–121

Boulanger M (2014a) Egyptian ceramics: compositional and descriptive database, Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory (core.tdar.org: tDAR id: 372352). https://doi.org/10.6067/XCV8ZC8187

Boulanger M (2014b) Cypriot ceramics: compositional and descriptive database, Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory (core.tdar.org, tDAR id: 372330). https://doi.org/10.6067/XCV8K35SJ5

Bourriau JD (1998) The role of chemical analysis in the study of Egyptian pottery. In: Eyre CJ (ed) Proceedings of the 7th International Congress of Egyptologists, Cambridge, 3–9 September 1995, Orientalia Lovaniensia Analecta, vol 82. Peeters, Leuven, pp 189–199

Bourriau JD, Nicholson PT (1992) Marl clay pottery fabrics of the New Kingdom from Memphis, Saqqara and Amarna. J Egypt Archaeol 78:29–91. https://doi.org/10.2307/3822066

Bourriau JD, Nordström H-Å (1993) Ceramic technology: clays and fabrics. Arnold, Bourriau 1993:143–190

Bourriau JD, Nicholson PT, Rose P (2000a) Pottery. In: Nicholson PT, Shaw I (eds) Ancient Egyptian materials and technology. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, pp 121–147

Bourriau, JD, Smith LMV, Nicholson PT (2000b) New Kingdom pottery fabrics: Nile clay and mixed Nile/marl clay fabrics from Memphis and Amarna. Egypt Exploration Society Occasional Publication 14. Egypt Exploration Society, London

Bourriau JD, Bellido A, Bryan N, Robinson V (2006) Egyptian pottery fabrics: a comparison between NAA groupings and the "Vienna System”. In: Czerny E et al. (eds) Timelines: studies in honour of Manfred Bietak, III. Orientalia Lovaniensia Analecta 149. Peeters, Leuven, pp 261–292

Chaviara A, Aloupi-Siotis E (2016) The story of a soil that became a glaze: chemical and microscopic fingerprints on the Attic vases, J Archaeol Sci: Reports 7. June 2016:510–518. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jasrep.2015.08.016

Cook RM (1954) CVA Great Britain 13, British Museum 8. Trustees of the British Museum, London

Defernez C (2002) Le poids de l'orientalisation et de l'hellénisation au travers des échanges et des productions céramiques dans l'angle nord-est du Delta égyptien. In: Blondé F, Ballet P, Salles JF (eds) Céramiques hellénistiques et romaines, productions et diffusion en Méditerranée orientale (Chypre, Égypte et côte syro-palestinienne). Maison de l'Orient et de la Méditerranée Jean Pouilloux, Lyon, pp 235–245

Defernez C (2011) Les témoignages d’une continuité de la culture matérielle saïte à l’époque perse: l’apport de l’industrie céramique. In: Devauchelle D (ed) La XXVIe dynastie: continuités et ruptures. Promenade saïte avec Jean Yoyotte. Actes du colloque international organisé les 26 et 27 novembre 2004 à l’Université Charles-de-Gaulle – Lille 3. Cybèle, Paris, pp 109–126

Defernez C, Marchand S (2016) État actuel de la recherche sur l’industrie amphorique égyptienne des IVe-IIIe siècles av. J.-C. In: Bader B, Knoblauch CM, Köhler EC (eds) Vienna 2—ancient Egyptian ceramics in the 21st century. Proceedings of the international conference held at the University of Vienna, 14th–18th of May, 2012, Orientalia Lovaniensia Analecta, vol 245. Peeters, Leuven, pp 127–154

Dupont P (1983) Classification et détermination de provenance des céramiques orientales archaïques d’Istros: Rapport préliminaire. Dacia N.S. 27:19–43

Dupont P, Thomas A (2006) Naukratis: les importations grecques orientales archaïques. In: Villing A, Schlotzhauer U (eds) Naukratis: Greek diversity in Egypt. Studies on East Greek pottery and exchange in the Eastern Mediterranean. British Museum Research Publication 162. British Museum Press, London, pp 77–84

Edgar CC (1905) Naukratis 1903, G.—minor antiquities. J Hellenic Studies 25:123–136

Friedrich T (2009) Über die Charakterisierung weißgrundiger Lekythen, ein Beitrag zur Schnittstelle Archäologie – Restaurierung – Materialkunde. Restauro 3:172–180

Gill JCR (2012) Ptolemaic 'Black Ware' from Mut el-Kharab. In: Knoblauch CM, Gill JC (eds) Egyptology in Australia and New Zealand 2009: proceedings of the conference held in Melbourne, September 4th–6th, BAR International Series, vol 2355. Archaeopress, Oxford, pp 15–25

Goren Y, Mommsen H, Klinger J (2011) Non-destructive provenance study of cuneiform tablets using portable X-ray fluorescence (pXRF). J Archaeol Sci 38(3):684–696. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jas.2010.10.020

Hancock RGV, Millet NB, Mills AJ (1986a) A rapid INAA method to characterize Egyptian ceramics. J. Arch Sci 13(2):107–117. https://doi.org/10.1016/0305-4403(86)90002-6

Hancock RGV, Aufreiter S, Elsokkary I (1986b) Nile alluvium: soil and ceramics. Bulletin of the Egyptological. Seminar 8:61–71

Klotz D (2013) The earliest representation of a potter’s kick-wheel in Egypt. ENiM - Égypte nilotique et méditerranéenne 6:169–176

Leclère F, Spencer AJ (2014) Tell Dafana reconsidered: the archaeology of an Egyptian frontier town. British Museum Research Publication 199. British Museum Press, London

Maish J, Svoboda M, Lansing-Maish S (2006) Technical studies of some Attic vases in the J. Paul Getty Museum. In: Cohen B (ed) The colors of clay, special techniques in Athenian vases. J. Paul Getty Museum, Malibu, pp 8–16

Mallory-Greenough LM, Greenough JD, Owen JV (1998) New data for old pots: trace-element characterization of ancient Egyptian pottery using ICP-MS. J Archaeol Sci 25(1):85–97. https://doi.org/10.1006/jasc.1997.0202

Mangone A, Giannossa LC, Colafemmina G, Laviano R, Traini A (2009) Use of various spectroscopy techniques to investigate raw materials and define processes in the overpainting of Apulian red figured pottery (4th century BC) from southern Italy. Microchem J 92(1):97–102. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.microc.2009.02.004

Marchand S (2002) Le maintien de la tradition pharaonique pour les productions des céramiques datées de l'époque ptolémaïque en Égypte. In: Blondé F, Ballet P, Salles JF (eds) Céramiques hellénistiques et romaines, productions et diffusion en Méditerranée orientale (Chypre, Égypte et côte syro-palestinienne). Maison de l'Orient et de la Méditerranée Jean Pouilloux, Lyon, pp 247–261

Marchand S (2011) La transposition céramique dans l'Égypte ancienne. In: Aston DA, Bader B, Gallorini C, Nicholson P, Buckingham S (eds) Under the potter’s tree: studies on ancient Egypt presented to Janine Bourriau on the occasion of her 70th birthday, Orientalia Lovaniensia Analecta, vol 204. Peeters, Leuven, pp 603–631

Marchand S (2013) Céramiques d’Égypte de la fin VIe siècle av. J.-C. au IIIe siècle av. J.-C.: entre tradition et innovation. In: Fenn N, Römer-Strehl C (eds) Networks in the Hellenistic world according to the pottery in the Eastern Mediterranean and beyond. BAR International series S2539. Archaeopress, Oxford, pp 239–253

Masson A (forthcoming) Scarabs, scaraboids and amulets. In: Villing et al. 2013-2019

Michel HV, Frierman JD, Asaro F (1976) Chemical composition patterns of ceramic wares from Fustat, Egypt. Archaeometry 18(1):85–92. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1475-4754.1976.tb00147.x

Michelaki K, Hancock RGV (2013) Reassessment of elemental concentration data of sediments from the western delta of the Nile River. In: Tykot RH (ed) Proceedings of the 38th international symposium on archeometry—May 10th-14th 2010, Tampa, Florida. Open J Archaeometry 1:e2

Mommsen H (2011) Provenancing of pottery. In: Nuclear techniques for cultural heritage research. IAEA Radiation Technology Series No. 2. International Atomic Energy Agency, Vienna, pp 41–70

Mommsen H (forthcoming) Evaluation of Manchester Neutron Activation Analysis (NAA) Data of 57 samples from MH III - LH IIB contexts at Tsoungiza. In: Rutter J (ed), Nemea valley archaeological project volume 3

Mommsen H, Sjöberg BL (2007) The importance of the ‘best relative fit factor’ when evaluating elemental concentration data of pottery demonstrated with Mycenaean sherds from Sinda, Cyprus. Archaeometry 49:357–369

Mommsen H, Kreuser A, Weber J (1988) A method for grouping pottery by chemical composition. Archaeometry 30(1):47–57. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1475-4754.1988.tb00434.x

Mommsen H, Kreuser A, Lewandowski E, Weber J (1991) Provenancing of pottery: a status report on neutron activation analysis and classification. In: Hughes M, Cowell M, Hook D (eds) Neutron activation and plasma emission spectrometric analysis in archaeology. British Museum Occasional Paper. British Museum, London, pp 57–65

Mommsen H with Cowell MR, Fletcher Ph, Hook D, Schlotzhauer U, Villing A, Weber S, Williams D (2006) Neutron activation analysis of pottery from Naukratis and other related vessels. In: Villing A, Schlotzhauer U (eds) Naukratis: Greek diversity in Egypt. Studies on East Greek pottery and exchange in the Eastern Mediterranean. British Museum Research Publication 162. British Museum Press, London, pp 69–76

Mommsen H, Schlotzhauer U, Villing A, Weber S (2012) Herkunftsbestimmung von archaischen Scherben aus Naukratis und Tell Defenneh durch Neutronenaktivierungsanalyse. In: Schlotzhauer U, Weber S, Griechische Keramik des 7. und 6. Jhs. v. Chr. aus Naukratis und anderen Orten in Ägypten. Archäologische Studien zu Naukratis III. Wernersche Verlagsgesellschaft, Mainz, pp 433–455

Mountjoy PA, Mommsen H (2001) Mycenaean pottery from Qantir-Piramesse, Egypt. The Annual of the British School at Athens 96:123–155. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0068245400005244

Noll W (1981) Bemalte Keramiken Altägyptens: Material, Rohstoffe und Herstellungstechnik. In: Arnold D (ed) Studien zur altägyptischen Keramik. Philip von Zabern, Mainz am Rhein, pp 103–138

Noll W (1991) Alte Keramiken und ihre Pigmente. E. Schweizerbart’sche Verlagsbuchhandlung (Nägele u. Obermiller), Stuttgart

Noll W, Holm R, Born L (1975) Painting of ancient ceramics. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl 14(9):602–613. https://doi.org/10.1002/anie.197506021

Oren ED (1984) Migdol: a new fortress on the edge of the eastern Nile Delta. Bull Am Sch Orient Res 256:7–44

Ownby M (2009) Petrographic and chemical analyses of select 4th Dynasty pottery fabrics from the Giza plateau. In: Rzeuska T, Wodzińska A (eds) Studies on Old Kingdom pottery. Neriton, Warsaw, pp 113–137

Ownby M (2011) Through the looking glass: the integration of scientific, ceramic, and archaeological information. In: Aston DA, Bader B, Gallorini C, Nicholson P, Buckingham S (eds) Under the potter’s tree: studies on ancient Egypt presented to Janine Bourriau on the occasion of her 70th birthday, Orientalia Lovaniensia Analecta, vol 204. Peeters, Leuven, pp 751–767

Ownby M (2016) Petrographic analysis of Egyptian ceramic fabrics in the Vienna system. In: Bader B, Knoblauch CM, Köhler EC (eds) Vienna 2—ancient Egyptian ceramics in the 21st century. Proceedings of the international conference held at the University of Vienna, 14th–18th of May, 2012, Orientalia Lovaniensia Analecta, vol 245. Peeters, Leuven, pp 459–470

Peacock DPS, Williams DF (1986) Amphorae and the Roman economy: an introductory guide. Longman archaeology series. Longman, London

Perlman I, Asaro E (1969) Pottery analysis by neutron activation. Archaeometry 11(1):21–52. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1475-4754.1969.tb00627.x

Redmount CA, Morgenstein ME (1996) Major and trace element analysis of modern Egyptian pottery. J Archaeol Sci 23(5):741–762. https://doi.org/10.1006/jasc.1996.0070

Riederer J (1989) The microscopic analysis of Egyptian pottery from the Old Kingdom. In: Schoske S (ed) Akten des vierten Internationalen Ägyptologen-Kongresses München 1985. Studien zur altägyptischen Kultur Beihefte I. Helmut Buske Verlag, Hamburg, pp 221–230

Rzeuska TI (2006) Saqqara II, Pottery of the Late Old Kingdom: funerary pottery and burial customs. Archeobooks, Warsaw

Schlotzhauer U (2012) Untersuchungen zur archaischen griechischen Keramik aus Naukratis. In: Schlotzhauer U, Weber S, Griechische Keramik des 7. und 6. Jhs. v. Chr. aus Naukratis und anderen Orten in Ägypten. Archäologische Studien zu Naukratis III. Wernersche Verlagsgesellschaft, Mainz, pp 21–194

Schlotzhauer U, Villing A (2006) East Greek pottery from Naukratis: the current state of research. In: Villing A, Schlotzhauer U (eds) Naukratis: Greek diversity in Egypt. Studies on East Greek pottery and exchange in the Eastern Mediterranean. British Museum Research Publication 162. British Museum Press, London, pp 53–68

Seifert M (2004) Herkunftsbestimmung archaischer Keramik am Beispiel von Amphoren aus Milet. BAR International Series 1233. Archaeopress, Oxford

Spataro M (2004) Pottery production in the Thar Desert (Sindh, Pakistan): three case-studies (Hindwari, Pir chebo, and Hingorja). Rivista di Archeologia 28:171–180

Spataro M, Villing A (2009) Scientific investigation of pottery grinding bowls from the Archaic and Classical Eastern Mediterranean. Br Mus Tech. Res Bull 3:89–100

Spencer J (2013-2019) Egyptian late period pottery. In: Villing et al. 2013-2019 http://www.britishmuseum.org/research/online_research_catalogues/ng/naukratis_greeks_in_egypt/material_culture_of_naukratis/late_period_pottery.aspx

Strange JF, Groh DE, Longstaff TR, Adan-Bayewitz D, Asaro F, Perlman I, Michel HV (1995) Excavations at Sepphoris: the location and identification of Shikhin, part II. Israel Explor J 45:171–187

Thomas RI (2013) Ceramics from the Saite occupation (Citadel). In: Spencer N (ed) Kom Firin II: the urban fabric and landscape. The British Museum, London, pp 179–185

Thomas RI (2013–2019a) Egyptian Late Period figures in terracotta and limestone. In: Villing et al. 2013-2019 http://www.britishmuseum.org/research/online_research_catalogues/ng/naukratis_greeks_in_egypt/material_culture_of_naukratis/late_period_figures.aspx

Thomas RI (2013–2019b) Ptolemaic and Roman figures, models and coffin-fittings in terracotta. In: Villing et al. 2013-2019 http://www.britishmuseum.org/research/online_research_catalogues/ng/naukratis_greeks_in_egypt/material_culture_of_naukratis/ptolemaic_and_roman_figures.aspx

Tite MS, Shortland A, Maniatis Y, Kavoussanaki D, Harris SA (2006) The composition of the soda-rich and mixed alkali plant ashes used in the production of glass. J Archaeol Sci 3(9):1284–1292. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jas.2006.01.004

Tobia SK, Sayre EV (1974) An analytical comparison of various Egyptian soils, clays, shales and some ancient pottery by neutron activation. In: Bishay A (ed) Recent advances in science and technology of materials III. Plenum Press, New York, pp 99–128. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4684-7233-2_7

Villing A (2006) Drab bowls’ for Apollo: the mortaria of Naukratis and exchange in the Archaic Eastern Mediterranean. In: Villing A, Schlotzhauer U (eds) Naukratis: Greek diversity in Egypt: studies on East Greek pottery and exchange in the Eastern Mediterranean. British Museum Research Publication 162. British Museum Press, London, pp 31–46

Villing A (2013-2019) Locally produced Archaic and Classical Greek pottery. In: Villing, et al. 2013–2019 http://www.britishmuseum.org/research/online_research_catalogues/ng/naukratis_greeks_in_egypt/material_culture_of_naukratis/local_greek_pottery.aspx

Villing A (2015) Egyptian-Greek exchange in the Late Period: the view from Nokradj-Naukratis. In: Robinson D, Goddio F (eds) Thonis-Heracleion in context. Oxford Centre for Maritime Archaeology Monograph 8. Oxford Centre for Maritime Archaeology, Oxford pp 229-246

Villing A, Bergeron M, Bourogiannis G, Johnston A, Leclère F, Masson A, Thomas R (2013-2019) Naukratis: Greeks in Egypt. British Museum Online Research Catalogue http://www.britishmuseum.org/naukratis

Vittmann G (2003) Ägypten und die Fremden im ersten vorchristlichen Jahrtausend. Kulturgeschichte der Antiken Welt 97. Philip von Zabern, Mainz

Walton M, Trentelman K, Cianchetta I, Maish J, Saunders D, Foran B, Mehta A (2015) Zn in Athenian black gloss ceramic slips: a trace element marker for fabrication technology. J American Ceramic Society 98(2):430–436

Acknowledgements

The help of the staff of the research reactor of the Reactor Institute Delft, Delft University of Technology, in irradiating the samples is thankfully acknowledged. We are grateful to Dr. Jeffrey Spencer and Dr. Ross I. Thomas (British Museum) for help with selecting, classifying and assessing samples; to Dr. John Meadows (ZBSA Germany), Dr. Alan Johnston (UCL/ICS London), Duncan Hook, Dr. Aurelia Masson-Berghoff, Nigel Meeks, Dr. Andrew Shapland (British Museum) for helpful discussion and comment; and the two anonymous referees for constructive criticism.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Electronic supplementary material

ESM 1

NAA raw data of 28 samples discussed in this article. Given are the concentrations C of 29 elements in µg/g (ppm), if not indicated otherwise, and below the average experimental uncertainties (errors), also in % of C, to indicate the precision of the Bonn NAA for the different elements (DOC 162 kb)

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Spataro, M., Mommsen, H. & Villing, A. Making pottery in the Nile Delta: ceramic provenance and technology at Naukratis, 6th–3rd centuries BC. Archaeol Anthropol Sci 11, 1059–1087 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12520-017-0584-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12520-017-0584-4