Abstract

Introduction

Usage patterns and effectiveness of a longer-acting formulation of insulin glargine at a strength of 300 units per milliliter (Gla-300) have not been studied in real-world clinical practice. This study evaluated differences in dosing and clinical outcomes before and after Gla-300 treatment initiation in patients with type 2 diabetes starting or switching to treatment with Gla-300 to assess whether the benefits observed in clinical trials translate into real-world settings.

Methods

This was a retrospective observational study using medical record data obtained by physician survey for patients starting treatment with insulin glargine at a strength of 100 units per milliliter (Gla-100) or Gla-300, or switching to treatment with Gla-300 from treatment with another basal insulin (BI). Differences in dosing and clinical outcomes before versus after treatment initiation or switching were examined by generalized linear mixed-effects models.

Results

Among insulin-naive patients starting BI treatment, no difference in the final titrated dose was observed in patients starting Gla-300 treatment versus those starting Gla-100 treatment [least-squares (LS) mean 0.43 units per kilogram vs 0.44 units per kilogram; P = 0.77]. Both groups had significant hemoglobin A1c level reductions (LS mean 1.21 percentage points for Gla-300 and 1.12 percentage points for Gla-100 ; both P < 0.001). The relative risk of hypoglycemic events after Gla-300 treatment initiation was lower than that after Gla-100 treatment initiation [0.31, 95% confidence interval (CI) 0.12–0.81; P = 0.018] at similar daily doses. The daily dose of BI was significantly lower after switching to treatment with Gla-300 from treatment with another BI (0.73 units per kilogram before switch vs 0.58 units per kilogram after switch; P = 0.02). The mean hemoglobin A1c level was significantly lower after switching than before switching (adjusted difference − 0.95 percentage points, 95% CI − 1.13 to − 0.78 percentage points ; P < 0.0001). Hypoglycemic events per patient-year were significantly lower (relative risk 0.17, 95% CI 0.11–0.26; P < 0.0001).

Conclusions

Insulin-naive patients starting Gla-300 treatment had fewer hypoglycemic events, a similar hemoglobin A1c level reduction, and no difference in insulin dose versus patients starting Gla-100 treatment. Patients switching to Gla-300 treatment from treatment with other BIs had significantly lower daily doses of BI, with fewer hypoglycemic events, without compromise of hemoglobin A1c level reduction. These findings suggest Gla-300 in a real-world setting provides benefits in terms of dosing, with improved hemoglobin A1c level and hypoglycemia rates.

Funding

Sanofi US Inc. (Bridgewater, NJ, USA).

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

According to the World Health Organization, worldwide there were 422 million people with diabetes in 2014 [1]. Type 2 diabetes (T2D) is a progressive disease, with many patients requiring insulin treatment to maintain target blood glucose levels [2]. As the disease progresses, more intensive treatment often becomes necessary to achieve or maintain glycemic control. It is often a considerable challenge to help patients achieve and maintain glycemic control, resulting in up to half of patients with diabetes in the USA failing to reach glycemic targets [3]. In the UK, only 40.2% of patients with T2D achieve the targets recommended to reduce the risk of diabetes complications [4]. A recent study conducted in the USA and across a diverse range of countries in the EU showed that 21% of patients starting basal insulin treatment achieved the recommended glycemic target within 3 months; the rates ranged from 28% in Germany to 8% in the UK. Two years after basal insulin treatment initiation, 28% of patients had reached their glycemic target [5].

Following lifestyle changes and monotherapy (most often with metformin), treatment guidelines recommend intensification of treatment in patients who are failing to obtain optimal glycemic control [6]. As well as the use of an oral antidiabetes drug (OAD) or a combination of different OADs, and the addition of glucagon-like peptide 1, another option is to initiate treatment with and titrate basal insulins and further intensify therapy either by addition of rapid-acting insulin or by administration of multiple daily injections of insulin [7]. Use of long-acting basal insulin analogs, such as insulin glargine at strength of 100 units per milliliter (Gla-100) and insulin detemir, has resulted in significant improvements in diabetes management in the past decade. Despite this, however, many patients and physicians are reluctant to initiate insulin therapy, and patients often do not adhere to insulin therapy if it is prescribed. Fear of injections and hypoglycemia are commonly cited reasons for this [8, 9].

A next-generation insulin glargine that contains 300 units per milliliter (Gla-300) and has an improved pharmacokinetic/pharmacodynamic (PK/PD) profile compared with Gla-100 was recently approved by the US Food and Drug Administration for the treatment of adults with type 1 diabetes (T1D) or T2D [10, 11]. Data show that, following injection, Gla-300 has slower release into the surrounding tissues compared with Gla-100, resulting in a more consistent plasma concentration of the drug and glucose-lowering effect, and a longer duration of action that fully covers a 24-h dose period with a single injection [12, 13]. Furthermore, data suggest that because of its more gradual release and stabler peak of action, Gla-300 is associated with lower incidence of hypoglycemia compared with first-generation basal insulins [12,13,14].

The efficacy and safety of Gla-300 were studied extensively in the EDITION series of clinical trials, which compared Gla-300 with Gla-100 in patients with T1D or T2D, with differing treatment backgrounds [15,16,17,18,19,20]. These treat-to-target clinical trials, which aimed to demonstrate noninferiority, consistently showed that hemoglobin A1c level decreased by equivalent amounts with Gla-300 and Gla-100 treatment, regardless of the type of diabetes or whether patients were insulin naive or switching from treatment with another basal insulin. Furthermore, despite a higher average daily insulin dose, hypoglycemia rates were lower in patients treated with Gla-300 compared with those treated with Gla-100 [15,16,17,18,19,20].

Efficacy and safety data, however, have all been obtained from clinical trials, in which benefits are demonstrated in a controlled environment for patients meeting specific inclusion and exclusion criteria. Usage patterns and effectiveness in real-world clinical practice for the broader population are yet to be studied. This study aims to evaluate differences in dosing and clinical outcomes before and after initiation of treatment with Gla-300 in patients with T2D starting or switching to treatment with Gla-300 so as to evaluate whether the benefits observed in clinical trials translate into the real-world setting.

Methods

Study Design

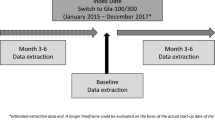

This was a retrospective observational study of data obtained by physician surveys and from medical records of 390 insulin-naive patients with T2D who started treatment with Gla-300 (n = 298) or Gla-100 (n = 92), and 163 patients who switched from treatment with insulin detemir or Gla-100 to treatment with Gla-300. The inclusion criteria for physicians were board certification in endocrinology, between 3 and 35 years in practice, at least 60% of their time spent treating/managing patients in a clinical setting, treating a minimum of ten patients with T2D monthly, and having treated a minimum of four patients with Gla-300 and one patient with Gla-100 in the past 6 months. The inclusion criteria for patients were age at least 18 years at the date of T2D diagnosis, and currently using either Gla-300 or Gla-100 (started within the past 6 months and used for at least 30 days). Patients in the naive sample were insulin naive before treatment initiation. Patients switching to treatment with Gla-300 from treatment with neutral protamine Hagedorn insulin were excluded from the switcher analysis as neutral protamine Hagedorn insulin is dosed twice daily.

Physicians completed patient record review forms via an online, self-administered survey using data from the medical records of the last four patients with T2D they had seen personally and in whom they had initiated treatment with Gla-300, and for the last patient with T2D in whom they had initiated treatment with Gla-100. As a limited number of patients switching to treatment with Gla-100 were enrolled in this study, a robust comparison between insulin groups was not feasible; therefore, outcomes were compared only for before switching versus after switching to treatment with Gla-300.

Patient Characteristics and Outcome Measures

The patient characteristics analyzed included age, sex, duration of diabetes, race, ethnicity, height, weight, diabetes-related complications, and health insurance type. The aspects of a patient’s diabetes history captured included date of diagnosis, date when the physician first started treating the patient, antidiabetes treatments, and number of office visits for T2D in the 6 months before the initiation of treatment with the study medications (Table 1). The treatment usage patterns analyzed included date of initiation, prior dosage if switching from another basal insulin, dosage initiated, and titrated dosage. The clinical measures analyzed included metabolic panel at initiation (or most recent), hemoglobin A1c level, and hypoglycemic events experienced 6 months before and after treatment initiation/switch. The physician’s reasons for choosing a therapy were also captured (Table 2).

Definitions of Dosing

Preinitiation/preswitch data on dosing were based on the physicians’ answers to the following request : “You indicated this patient was on a basal insulin. Please record the brand name and total number of units per day for this basal insulin that was prescribed to this patient.”

Postinitiation/postswitch data on dosing were based on the physicians’ answers to the following request: “Please record the total number of units of (Gla-300 or Gla-100) that this patient has been titrated to and now is considered their maintenance dose.”

Definitions of Hypoglycemia

Preinitiation/preswitch data on hypoglycemia were based on the physicians’ answers to the following questions:

-

“In the 6 months prior to (Gla-300 or Gla-100) initiation, has this patient reported experiencing any hypoglycemic events?” (Yes/no/don’t know).

-

“In the 6-month period prior to (Gla-300 or Gla-100) initiation, how many hypoglycemic events did this patient report experiencing?” (Number of events).

Postinitiation/postswitch data on hypoglycemia were based on the physicians’ answers to the following questions:

-

“Since being initiated on Gla-300 or Gla-100, has this patient reported experiencing any hypoglycemic events?” (Yes/no/don’t know).

-

“How many hypoglycemic events has this patient reported experiencing since being initiated on Gla-300 or Gla-100?” (Number of events).

Statistical Analyses

Descriptive statistics were reported to characterize patient profiles and change in clinical outcomes (e.g., mean and standard deviation for continuous variables and percentages for categorical variables). Patients who started treatment with Gla-300 were compared with patients who started treatment with Gla-100 with regard to demographics, diagnosis history, and clinical-profile variables with use of a chi-square test for categorical variables and a two-sample Student t test for continuous variables.

Generalized linear mixed-effects models adjusting the data for demographics (e.g., age, sex, health insurance status) and clinical characteristics (e.g., prior OAD treatments, body mass index) were used to examine differences in dosing patterns and clinical outcomes before treatment initiation versus after treatment initiation or switching, accounting for the differing follow-up times. This helped to account for the confounders. Least-squares (LS) means, along with associated 95% confidence intervals (CIs) and P values, were reported from generalized linear mixed-effects models.

Compliance with Ethics Guidelines

This article is based on previously conducted studies and does not involve any new studies of humans or animals performed by any of the authors.

Results

Patient Baseline Characteristics

Data were analyzed from 390 insulin-naive patients starting basal insulin treatment, of whom 92 started treatment with Gla-100 and 298 started treatment with Gla-300. For the switching analysis, data from 163 patients were analyzed, of whom 118 switched from treatment with Gla-100 and 45 switched from treatment with insulin detemir. Patient baseline characteristics are shown in Table 1 and were comparable for the three groups. Nearly three quarters of patients switching to treatment with Gla-300 from treatment with another basal insulin switched from treatment with Gla-100 (Table 1).

Reasons for Therapy Choices

The most commonly cited reason that physicians gave for choosing a therapy for their patient was “efficacy,” at about 45% in all treatment groups (Table 2). Another result of note was that physicians commonly prescribed Gla-100 in patients starting therapy because they were comfortable/familiar with the treatment. “Hypoglycemia concerns” was the most commonly cited reason for patients switching to treatment with Gla-300 (27.0%); this was the reason given for initiating Gla-300 treatment by 19.5% of physicians and for initiating Gla-100 treatment by 13.0% of physicians. Similarly, “better control” and “better patient adherence” were the most commonly cited reasons for switching patients to treatment with Gla-300 (33.1% and 41.1%, respectively); these reasons were cited for initiating Gla-300 treatment by 22.5% and 20.5% of physicians, respectively, and for initiating Gla-100 treatment by 16.3% and 14.1% of physicians, respectively (Table 2).

Preinitiation and Postinitiation Dosing

After other covariates had been controlled for, the initial prescribed dose of Gla-300 (LS mean 0.331 units per kilogram) was comparable to that of Gla-100 (LS mean 0.339 units per kilogram; P = 0.86). No difference in the final titrated dose was observed in patients who started treatment with Gla-300 versus patients who started treatment with Gla-100 (LS mean 0.43 units per kilogram vs 0.44 units per kilogram; P = 0.77) (Fig. 1).

After other covariates had been controlled for, the daily dose of basal insulin was significantly lower after switching to treatment with Gla-300 (Fig. 2), with the adjusted difference between the preswitch and postswitch values being −0.15 units per kilogram (95% CI −0.28 to −0.02 units per kilogram; P = 0.02).

Preinitiation and Postinitiation Hemoglobin A1c Level and Hypoglycemia

Compared with before treatment initiation, the mean hemoglobin A1c level was significantly lower after initiation of Gla-300 or Gla-100 treatment (LS mean change 1.21 percentage points and 1.12 percentage points , respectively; both P < 0.001); the difference was not statistically significant between Gla-300 and Gla-100 (P = 0.62) (Fig. 3a). The annualized mean number of hypoglycemic events per patient-year was significantly lower following initiation of Gla-300 treatment versus Gla-100 treatment at similar daily doses (Fig. 3b) and the relative risk of hypoglycemic events after initiation of Gla-300 treatment versus Gla-100 treatment was 0.31 (95% CI 0.12–0.81; P = 0.018).

Hemoglobin A1c (A1C) level (a) and hypoglycemic events (b) for insulin-naive patients starting treatment with insulin glargine at a strength of 100 units per milliliter (Gla-100) or insulin glargine at a strength of 300 units per milliliter (Gla-300). In b the relative risk of hypoglycemic events after starting Gla-300 treatment versus Gla-100 treatment was 0.31 (95% confidence interval 0.12–0.81; P = 0.018). LS least squares

Regardless of prior basal insulin dosing frequency (P = 0.976), the mean hemoglobin A1c level was significantly lower after switching to treatment with Gla-300 from treatment with another basal insulin (Fig. 4a ). The adjusted difference between the preswitch and postswitch values was − 0.95 percentage points (95% CI − 1.13 to − 0.78 percentage points ; P < 0.0001). Regardless of prior basal insulin dosing frequency (P = 0.845), the annualized mean number of hypoglycemic events per patient-year was significantly lower after switching to treatment with Gla-300 from treatment with another basal insulin (Fig. 4b). The relative risk of hypoglycemic events after switching to treatment with Gla-300 was 0.17 (95% CI 0.11–0.26; P < 0.0001).

Hemoglobin A1c (A1C) level (a) and hypoglycemic events per year (b) for patients switching to treatment with insulin glargine at a strength of 300 units per milliliter (Gla-300) from treatment with another basal insulin. Asterisk regardless of prior basal insulin dosing frequency (once daily vs twice daily: P = 0.976), dagger 95% confidence interval − 1.13 to − 0.78 percentage points (P = 0.001), double dagger relative risk 0.17 (95% confidence interval 0.11–0.26)

Discussion

As Gla-300 was only relatively recently approved by the US Food and Drug Administration and the European Medicines Agency, this study aimed to investigate its impact on patients with T2D (both those starting basal insulin treatment with Gla-300 or switching from treatment with another basal insulin) in a real-world setting, with a focus on patients in the USA. These data provide useful insights regarding actual medication use patterns and clinical outcomes beyond the confines of clinical trials.

An important rationale for use of Gla-300 rather than first-generation basal insulins, such as Gla-100 or insulin detemir, is that in addition to reduced injection volumes it is also expected to result in fewer instances of hypoglycemia because of its improved PK/PD profile [12, 13, 21]. It has been shown that this is because Gla-300 has more gradual release from the subcutaneous tissue compared with Gla-100, resulting in 24 h or longer coverage [12, 13, 22]. Patients in clinical trials who switch from twice-daily basal insulin treatment to once-daily Gla-300 treatment show a dosing increase of 0.28–0.38 units per kilogram per day [23]. The significant difference in the number of units of insulin received after switching to treatment with Gla-300 from treatment with another basal insulin (adjusted difference of 0.15 units per kilogram following the switch to treatment with Gla-300) could suggest that changes in insulin dosing in the real-world setting are smaller than those seen in clinical trials. Further studies are needed to provide more insight.

Our results also support the findings of clinical trials demonstrating reduced hypoglycemia rates in patients treated with Gla-300 compared with first-generation basal insulins [15,16,17,18,19,20]. Although this might be expected in patients switching to treatment with Gla-300 from treatment with other basal insulins, it is interesting to note in our results that hypoglycemic events per patient-year were reduced in insulin-naive patients starting treatment with Gla-300 versus those starting treatment with Gla-100. Although the rates of hypoglycemia were already very low before treatment initiation (0.12 events per patient-year), the difference was statistically significant. Patients starting basal insulin treatment for the first time may take particular care with regard to monitoring their blood glucose levels, and have increased awareness of the possibility of hypoglycemia. This effect may be heightened further in a clinical trial setting, which might have contributed to the observed reduction in hypoglycemia rates in these patients. It is also possible that hypoglycemic events before initiation were underreported, as such episodes were captured through health care encounters and relatively short follow-up times. Furthermore, the use of sulfonylureas after treatment initiation/switching was lowest in patients switching to treatment with Gla-300 (11.7%) followed by patients starting treatment with Gla-300 (27.5%), and was highest in patients starting treating treatment with Gla-100 (34.8%), which may contribute to this result.

The improved PK/PD profile of Gla-300 means that it has the potential to improve glycemic target achievement [21]. As would be expected, insulin-naive patients starting treatment with either Gla-300 or Gla-100 had significant reductions in hemoglobin A1c level. Patients switching to treatment with Gla-300 from treatment with other basal insulins had similar hemoglobin A1c level reductions as patients starting treatment with Gla-300 . As clinical trials reported lower rates of hypoglycemia with Gla-300 compared with Gla-100, patients requiring treatment intensification but who have concerns regarding hypoglycemia would be more likely to be switched to treatment with Gla-300. Concerns regarding hypoglycemia are often cited as reasons for reluctance to start and intensify insulin therapy, both by physicians and by patients [8, 9, 24]. Switching to treatment with Gla-300 may allow such patients to properly adhere to their treatment regimens, therefore improving their glycemic control.

It is possible that the patients selected for study inclusion represent a “convenience” sample. That is, rather than strictly following the protocol and selecting the most recent patients prescribed either Gla-300 or Gla-100, physicians being surveyed via the Internet may have selected the records that were most readily available. Therefore, the findings may not be generalizable to the overall US population of patients with T2D receiving Gla-300. Additionally, because of the subjective nature of some of the physician-reported measures and reliance on data abstraction from patient records, nondifferential recall biases may have introduced measurement error. As the data were obtained only from physicians who agreed to participate in the study and contributed data, these may not be representative of all US physicians treating patients with T2D. Indeed, physicians agreeing to take part in such studies are more likely to be closely engaged in their patients’ treatment and well-being. Furthermore, the very fact that they were taking part in this study may have resulted in physicians being especially attentive regarding their patients’ treatment and well-being.

The study was designed to provide a retrospective description of current treatment patterns and outcomes and is, therefore, subject to inherent confounding (due to different patient and disease characteristics for patients receiving different treatment regimens) and to confounding from unmeasured variables. The current data do not support a robust analysis of concomitant medication use, because of the timing of medical record collection. The mean follow-up time was 4 months, and only a small proportion of patients had a sufficiently long follow-up time. There was also a lack of a comparator group in the cohort that switched to treatment with Gla-300 from treatment with another basal insulin, and not all patients provided data both before and after the switch.

Additional real-world studies, both prospective and retrospective, with larger sample sizes and longer follow-up times are needed to confirm these findings.

Conclusion

In this real-world study of patients with T2D, insulin-naive patients starting treatment with Gla-300 compared with those starting treatment with Gla-100 experienced fewer hypoglycemic events and had a similar hemoglobin A1c level reduction, with no difference in daily insulin dose. Patients switching to treatment with Gla-300 from treatment with Gla-100 or another basal insulin had a significantly lower daily dose of basal insulin, with fewer hypoglycemic events and no compromised hemoglobin A1c level reduction. Regardless of the frequency of prior basal insulin dosing, significant reductions in hemoglobin A1c level and the number of hypoglycemic events were observed with Gla-300.

These findings suggest that in a real-world setting Gla-300 provides benefits in terms of reduced hemoglobin A1c level and rates of hypoglycemia.

References

World Health Organization. Global report on diabetes. http://www.who.int/diabetes/global-report/en/ (2016). Accessed 21 Mar 2017.

Inzucchi SE, Bergenstal RM, Buse JB, et al. Management of hyperglycemia in type 2 diabetes: a patient-centered approach. Diabetes Care. 2012;35:1364–79.

Stark Casagrande S, Fradkin JE, Saydah SH, et al. The prevalence of meeting A1C, blood pressure, and LDL goals among people with diabetes, 1988-2010. Diabetes Care. 2013;36:2271–9.

Health and Social Care Information Centre (HSCIC). National Diabetes Audit 2015/16: report 1: care processes and treatment targets. 2017. http://content.digital.nhs.uk/catalogue/PUB23241/nati-diab-rep1-audi-2015-16.pdf. Accessed 22 Jun 2017.

Mauricio D, Meneghini L, Seufert J, et al. Glycaemic control and hypoglycaemia burden in patients with type 2 diabetes initiating basal insulin in Europe and the USA. Diabetes Obes Metab. 2017;19:1155–64.

Inzucchi SE, Bergenstal RM, Buse JB, et al. Management of hyperglycemia in type 2 diabetes, 2015: a patient-centered approach: update to a position statement of the American Diabetes Association and the European Association for the Study of Diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2015;38:140–9.

Marathe PH, Gao HX, Close KL. American Diabetes Association standards of medical care in diabetes 2017. J Diabetes. 2017;9:320–4.

Peyrot M, Barnett AH, Meneghini LF, Schumm-Draeger PM. Factors associated with injection omission/non-adherence in the global attitudes of patients and physicians in insulin therapy study. Diabetes Obes Metab. 2012;14:1081–7.

Peyrot M, Barnett AH, Meneghini LF, Schumm-Draeger PM. Insulin adherence behaviours and barriers in the multinational global attitudes of patients and physicians in insulin therapy study. Diabet Med. 2012;29:682–9.

US Food and Drug Administration. Approval package. https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/scripts/cder/daf/index.cfm?event=overview.process&ApplNo=206538. Accessed 19 Oct 2017.

US Department of Health and Human Services. FDA-approved diabetes medicines. http://www.fda.gov/forpatients/illness/diabetes/ucm408682.htm (2017). Accessed 23 Feb 2017.

Shiramoto M, Eto T, Irie S, et al. Single-dose new insulin glargine 300 U/ml provides prolonged, stable glycaemic control in Japanese and European people with type 1 diabetes. Diabetes Obes Metab. 2015;17:254–60.

Becker RH, Dahmen R, Bergmann K, et al. New insulin glargine 300 units·mL−1 provides a more even activity profile and prolonged glycemic control at steady state compared with insulin glargine 100 units·mL−1. Diabetes Care. 2015;38:637–43.

Bergenstal RM, Bailey TS, Rodbard D, et al. Comparison of insulin glargine 300 units/mL and 100 units/mL in adults with type 1 diabetes: continuous glucose monitoring profiles and variability using morning or evening injections. Diabetes Care. 2017;40:554–60.

Riddle MC, Bolli GB, Ziemen M, et al. New insulin glargine 300 units/mL versus glargine 100 units/mL in people with type 2 diabetes using basal and mealtime insulin: glucose control and hypoglycemia in a 6-month randomized controlled trial (EDITION 1). Diabetes Care. 2014;37:2755–62.

Yki-Järvinen H, Bergenstal R, Ziemen M, et al. New insulin glargine 300 units/mL versus glargine 100 units/mL in people with type 2 diabetes using oral agents and basal insulin: glucose control and hypoglycemia in a 6-month randomized controlled trial (EDITION 2). Diabetes Care. 2014;37:3235–43.

Bolli GB, Riddle MC, Bergenstal RM, et al. New insulin glargine 300 U/ml compared with glargine 100 U/ml in insulin-naïve people with type 2 diabetes on oral glucose-lowering drugs: a randomized controlled trial (EDITION 3). Diabetes Obes Metab. 2015;17:386–94.

Home PD, Bergenstal RM, Bolli GB, et al. New insulin glargine 300 units/mL versus glargine 100 units/mL in people with type 1 diabetes: a randomized, phase 3a, open-label clinical trial (EDITION 4). Diabetes Care. 2015;38:2217–25.

Matsuhisa M, Koyama M, Cheng X, et al. New insulin glargine 300 U/ml versus glargine 100 U/ml in Japanese adults with type 1 diabetes using basal and mealtime insulin: glucose control and hypoglycaemia in a randomized controlled trial (EDITION JP 1). Diabetes Obes Metab. 2016;18:375–83.

Terauchi Y, Koyama M, Cheng X, et al. New insulin glargine 300 U/ml versus glargine 100 U/ml in Japanese people with type 2 diabetes using basal insulin and oral antihyperglycaemic drugs: glucose control and hypoglycaemia in a randomized controlled trial (EDITION JP 2). Diabetes Obes Metab. 2016;18:366–74.

Owens DR. Pharmacokinetics and pharmadynamics of insulin glargine 300 U/mL in the treatment of diabetes and their clinical relevance. Expert Opin Drug Metab Toxicol. 2016;12:977–87.

Steinstraesser A, Schmidt R, Bergmann K, et al. Investigational new insulin glargine 300 U/ml has the same metabolism as insulin glargine 100 U/ml. Diabetes Obes Metab. 2014;16:873–6.

Roussel R, d’Emden M, Fisher M, et al. Switching from twice-daily basal insulin to once-daily new insulin glargine 300U/mL (Gla-300): an analysis in people with T2DM (EDITION 1 and 2). Diabetes Technol Ther. 2016;18(Suppl 1):140.

Davies MJ, Gagliardino JJ, Gray LJ, et al. Real-world factors affecting adherence to insulin therapy in patients with type 1 or type 2 diabetes mellitus: a systematic review. Diabet Med. 2013;30:512–24.

Acknowledgements

Funding

This study was funded by Sanofi US Inc. (Bridgewater, NJ, USA). Journal article processing charges were funded by Sanofi US Inc. (Bridgewater, NJ, USA).

Medical writing assistance

The authors received writing/editorial support in the preparation of the manuscript from Grace Richmond of Excerpta Medica, funded by Sanofi US Inc. (Bridgewater, NJ, USA).

Authorship

All authors had full access to all of the data in this study and take complete responsibility for the integrity of the data and accuracy of the data analysis. All named authors meet the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors (ICMJE) criteria for authorship of this article, take responsibility for the integrity of the work as a whole, and have given final approval for the version to be published.

Data Availability

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Disclosures

Shaloo Gupta is an employee of Kantar Health, which received funding from Sanofi to conduct this study. Hongwei Wang is an employee of Sanofi. Neil Skolnik is on the advisory panel for AstraZeneca, Teva, Lilly, Boehringer Ingelheim, Sanofi, Janssen Pharmaceuticals, and Intarsia, is a speaker for AstraZeneca and Boehringer Ingelheim, and has received research support from Sanofi, AstraZeneca, and Boehringer Ingelheim. Liyue Tong is an employee of PRO Unlimited, under contract with Sanofi at the time of the study. Ryan M. Liebert is an employee of Kantar Health, which received funding from Sanofi to conduct this study. Lulu K. Lee is an employee of Kantar Health, which received funding from Sanofi to conduct this study. Peter Stella is an employee of Sanofi. Anna Cali is an employee of Sanofi. Ronald Preblick is an employee of Sanofi.

Compliance with Ethics Guidelines

This article is based on previously conducted studies and does not involve any new studies of humans or animals performed by any of the authors.

Open Access

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/), which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Enhanced Content

To view enhanced content for this article go to http://www.medengine.com/Redeem/7CFCF0601F322B55.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0), which permits use, duplication, adaptation, distribution, and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Gupta, S., Wang, H., Skolnik, N. et al. Treatment Dosing Patterns and Clinical Outcomes for Patients with Type 2 Diabetes Starting or Switching to Treatment with Insulin Glargine (300 Units per Milliliter) in a Real-World Setting: A Retrospective Observational Study. Adv Ther 35, 43–55 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12325-017-0651-3

Received:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12325-017-0651-3