Abstract

Introduction

This analysis aimed to investigate the effectiveness and safety profile of pirfenidone for the treatment of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF) in clinical practice.

Methods

Clinical records of patients diagnosed with mild-to-moderate IPF (as per European Medicines Agency indication) and receiving pirfenidone treatment across three centers in Belgium and the Netherlands between April 2011 and October 2013 were retrospectively collected from patient notes at 3-month intervals. Pulmonary function measurements, including % predicted forced vital capacity (%FVC) and % predicted diffusing capacity of the lungs for carbon monoxide (%DLCO), were analyzed from 6 months prior to pirfenidone treatment up to 12 months of treatment. Decline in lung function, defined as an absolute ≥10% decline in FVC from baseline or death at 12 months, was also analyzed. Safety data were included for all follow-up visits.

Results

In the pooled cohort (n = 63), patients were mostly men (84.1%) and current or former smokers (79.4%). Average baseline %FVC and %DLCO were 75.0% and 47.9%, respectively. 69.8% of patients had a high-resolution computed tomography scan with a definite usual interstitial pneumonia pattern, and 46% had a surgical lung biopsy. The mean decline in %FVC for 32 patients with available data was 4.8% from −6 months to baseline (p = 0.002) and 0.8% from baseline to 6 months (p = 0.516). Across these time intervals, a lesser decline in DLCO was similarly observed during therapy. At 12 months, ten patients had an %FVC decline ≥10% or died. Loss of appetite (25.3%) and nausea (11.1%) were the most frequent gastrointestinal side effects. Nausea was the most highly cited reason for discontinuation (7.9%).

Conclusions

In this clinical practice cohort, pirfenidone showed effectiveness and safety profiles consistent with those seen in the Phase III clinical study ASCEND (ClinicalTrials.gov #NCT01366209). These results highlight the challenges and benefits associated with pirfenidone treatment in clinical practice.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF) is a rare, progressive, irreversible and ultimately fatal chronic lung disease, with a median survival time of 2–5 years [1–4]. It is the most common of the idiopathic interstitial pneumonias and its incidence and prevalence appear to be rising. In the UK, disease incidence during the 2006–2008 calendar period was 5.10 cases per 100,000 person-years, which was sixfold higher than during the 1968–1972 calendar period (0.92 cases per 100,000 person-years) [5]. In the USA, annual incidence of IPF in the Medicare population remained stable between 2001 and 2011, with an overall estimate of 93.7 cases per 100,000 person-years, while the annual cumulative prevalence increased steadily from 202.2 cases per 100,000 in 2001 to 494.5 cases per 100,000 in 2011 [6].

Pirfenidone is an oral anti-fibrotic drug with anti-inflammatory properties and was the first drug approved for the treatment of adult patients with IPF by the European Medicines Agency (EMA) in 2011, followed by approval by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) in 2014 [5, 6]. Nintedanib, a tyrosine kinase inhibitor, has since been approved for IPF by the FDA [7] and the EMA [8] (in 2014 and 2015, respectively).

Pirfenidone has been studied in four Phase III clinical trials: three multinational studies [CAPACITY 004 (ClinicalTrials.gov #NCT00287716) and 006 (ClinicalTrials.gov #NCT00287729), and ASCEND (ClinicalTrials.gov #NCT01366209)] and one Japanese study [9–11]. Compared with placebo, pirfenidone treatment was shown to reduce forced vital capacity (FVC) decline, reduce decline in 6-min walk test distance and increase progression-free survival. Data from the randomized, double-blind placebo-controlled trial, ASCEND, were published in May 2014 [11]. In 555 patients with IPF, pirfenidone slowed disease progression compared with placebo; there was a relative reduction of 47.9% in the proportion of patients who had an absolute decline of ≥10% in the % predicted FVC (%FVC) or who died. A pre-specified pooled analysis of the CAPACITY and ASCEND studies at 52 weeks (12 months) showed that treatment with pirfenidone significantly reduced all-cause mortality by 48% [hazard ratio (HR) 0.52, 95% confidence interval (CI) 0.31–0.87, p = 0.01] and IPF-related mortality by 68% (HR 0.32, 95% CI 0.14–0.76, p = 0.006) [11].

The most commonly reported adverse reactions during clinical study experience with pirfenidone compared with placebo were nausea (32.4% vs. 12.2%), rash (26.2% vs. 7.7%), diarrhea (18.8% vs. 14.4%), fatigue (18.5% vs. 10.4%), dyspepsia (16.1% vs. 5.0%), anorexia (11.4% vs. 3.5%), headache (10.1% vs. 7.7%), and photosensitivity reaction (9.3% vs. 1.1%), respectively [12].

Randomized controlled trials have long been considered the gold standard for generating clinical data. However, given the standardization required, such as the requirement for a robust trial design with clearly defined inclusion and exclusion criteria, such trials do not capture all information that is relevant for clinical practice. Indeed, real-world clinical experience can provide important complementary information on the use of investigational/new treatments. Both clinical experience with pirfenidone for the treatment of IPF, and information available for health-care professionals concerning the use of pirfenidone in daily clinical practice, are important to communicate, especially as the literature is currently sparse on these topics.

Here, we report early clinical experiences of the management of IPF treated with pirfenidone at three centers in Belgium and the Netherlands and compare these data with results from a recent Phase III study (ASCEND).

Methods

The Named Patient Program

To facilitate patient access to pirfenidone in European countries where it was not immediately available following EU approval, InterMune International AG offered pirfenidone (Esbriet®, Roche, Basel, Switzerland) to individual patients upon the request of their treating physician in the context of a European named patient program (NPP, known as Medical Need Program in Belgium according to national legislation). This program terminated once pirfenidone became commercially available in the participating European countries.

In Belgium and the Netherlands, eligible patients (see criteria below) were informed by their treating pulmonologist about the possibility of entering the NPP to obtain treatment with pirfenidone.

Data from enrolled patients were retrospectively collected from three centers (two in the Netherlands and one in Belgium) between April 2011 and October 2013 (2 years of analyzable data were available).

Patients

Eligible patients were diagnosed with IPF according to the American Thoracic Society and European Respiratory Society guidelines [4], which include a multidisciplinary diagnostic approach involving clinical, radiological and, if necessary, histopathological findings.

Inclusion criteria for this retrospective analysis comprised a diagnosis of IPF with %FVC ≥50 and % predicted diffusing capacity for carbon monoxide (%DLCO) ≥30. Patients with severe renal impairment (creatinine clearance rate below 30 mL/min), severe hepatic impairment, or with alcohol dependence were excluded from the program. Patient permissions for data collection and usage were granted according to specific local requirements of the medical ethical committee at each participating center.

Treatment

Pirfenidone was given orally with food. The initial dose of one capsule (267 mg pirfenidone) three times per day (801 mg/day; 3 × 1) was increased after 1 week to two capsules, three times per day (1602 mg/day; 3 × 2), and after another week to the full approved maintenance dose of three capsules, three times per day (2403 mg/day; 3 × 3) [12].

Dose modifications to manage adverse events (AEs) were adopted on an individual patient basis and involved a down-titration from the full 3 × 3 dosing regimen to a 3 × 2 or 3 × 1 regimen, or an individual scheme, with dosing sometimes re-adjusted after the initial modification according to the patient’s response.

Analysis of Pulmonary Function and Safety

Effectiveness and safety data were retrospectively collected from patient notes at 3-month intervals. Pulmonary function measurements, including %FVC and %DLCO, were analyzed from 6 months before the start of pirfenidone treatment up to 12 months of treatment. Safety data were included for all follow-up visits. Missing data were not imputed.

Decline in lung function was defined in the same way as in the ASCEND study: an absolute ≥10% decline in %FVC or death at week 52 (12 months). The proportion of patients with a decline of ≥10% in %FVC from baseline or who died was analyzed at 3 monthly intervals up to 12 months using all available data (no censoring for missing data). A Kaplan–Meier time-to-event analysis was additionally undertaken, whereby patients with missing data were censored at their last FVC assessment (event defined as an absolute ≥10% decline in %FVC or death). Where available, %FVC and %DLCO data from 6 months prior to pirfenidone initiation were collected and compared with baseline and 6-month values using a paired t test (SAS® 9.2. SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA).

All procedures followed were in accordance with the ethical standards of the responsible committee on human experimentation (institutional and national) and with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975, as revised in 2000 and 2008. Patient permissions for data collection and usage were granted according to specific local requirements of the medical ethical committee at each participating center. Additional informed consent was obtained from all patients for which identifying information is included in this article.

Results

Patients

Patient demographics and baseline characteristics in the three centers (Center 1: n = 29, The Netherlands; Center 2: n = 21, Belgium; Center 3: n = 13, The Netherlands) are reported in Table 1. Patients’ mean [standard deviation (SD)] age at the start of pirfenidone treatment was 66.8 (8.9) years in the pooled cohort. A high percentage of patients in each center were current or former smokers and the majority were male (≥80%). Across all centers, 69.8% of patients had a high-resolution computed tomography (HRCT) scan showing a definite usual interstitial pneumonia (UIP) pattern. In 46% of the patients, a surgical lung biopsy was performed. Baseline mean (SD) %DLCO and %FVC were 47.9% (12.4) and 75.0% (16.5), respectively, for the pooled cohort.

Pirfenidone Administration

Dose escalation at treatment initiation was followed as described [12], except for one patient in Center 2 who remained on the initial 3 × 1 dose due to gastrointestinal (GI) AEs.

Pulmonary Function

Among patients with complete FVC data between 6 months prior to (−6 months) and 6 months after (6 months) initiation of pirfenidone therapy (n = 32), the mean decline in %FVC from −6 months to baseline (pre-therapy) was 4.8% (p = 0.002) and from baseline to 6 months (on therapy), 0.8% (p = 0.516), giving a clear reduction in FVC decline during the 6 months after pirfenidone initiation (p = 0.082; Fig. 1). In a similar analysis of %DLCO (n = 26), the decline from −6 months to baseline was 6.7% (p = 0.003), whereas from baseline to 6 months the decline was lower (3.0%), but remained significant (p = 0.033; Fig. 2) and did not differ significantly from the decline in the 6 months before pirfenidone initiation (p = 0.214).

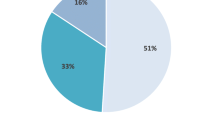

A categorical analysis of %FVC was undertaken in the above 32 patients with complete %FVC data to investigate lung function progression upon treatment with pirfenidone; the proportion of patients with <5% decline in FVC increased after therapy and there were fewer patients with >10% FVC decline than before therapy (Fig. 3).

The proportion of patients with FVC decline ≥10% or death across four study time points ranging from 3 to 12 months is illustrated in Table 2. At 12 months, 4 patients had a ≥10% decline in FVC compared with baseline; 35 patients remained stable, while 3 patients had ≥10% increase in FVC compared with baseline (Table 2). Ten patients had a ≥10% FVC decline or death, which was 21% of patients treated with pirfenidone for 12 months (10/48 patients).

Finally, a Kaplan–Meier plot of progression-free survival over 12 months, incorporating %FVC decline ≥10% from baseline or death, is presented in Fig. 4. At 12 months, the estimated progression-free survival rate was 0.78.

Mortality

Six (9.5%) patients died between baseline and 12 months (all-cause mortality). IPF was listed as the cause of death in 5 (7.9%) patients.

Safety and Tolerability

A total of 57.1% of patients in the pooled cohort experienced treatment-emergent AEs (Table 3), with the frequency of treatment-emergent AEs differing substantially between the centers (82.8%, 38.1% and 38.5% of patients in Centers 1, 2, and 3, respectively).

Loss of appetite and nausea were the most frequent AEs, reported in 25.3% and 11.1% of the pooled cohort, respectively. Photosensitivity reaction (see example in Fig. 5) and rash were reported in 9.5% and 6.3% of patients in the pooled cohort, respectively.

A total of 12 patients (19%) in the pooled cohort discontinued pirfenidone due to treatment-emergent AEs (Table 4); nausea was the most highly cited reason for discontinuation due to AEs (7.9% of patients in the pooled cohort). Other reasons for discontinuation were deemed unrelated to study drug, including six deaths (all-cause mortality) and two lung transplantations.

Management of AEs

Adverse event management was conducted on an individual patient basis to facilitate continued therapy whenever possible and included pirfenidone dose reduction, treatment of side effects, and/or discontinuation according to the extent and tolerability of AEs.

Following an AE, 41.2% of patients in the pooled cohort experienced a period on a modified dose of pirfenidone. Modified dosing was prescribed to different extents across the three centers, reflecting differences in the rate of AEs reported in each of them (82.8%/58.3%, 38.1%/29.4%, and 38.5%/20% of patients reported AEs/had dose modification in Centers 1, 2, and 3 respectively). Treatment interruption, in contrast to lowering the dose, usually led to prolonged or permanent discontinuation of therapy. Two patients from Center 1 who stopped treatment for at least 1 day after experiencing AEs were able to resume dosing (and in one case a full dose) after experiencing AEs.

Discussion

A typical Phase III clinical study is well defined to maximize chances of a reliable outcome, generally involving clear inclusion criteria (with limited co-morbidities and concomitant medications), central review of key disease parameters, and strict management protocols. This always yields the question: “To which extent can results from clinical trials be extrapolated to daily clinical practice?”

In the discussion below, we put the experience with pirfenidone obtained from this clinical practice cohort of patients with IPF into perspective by comparing it with data from the recent Phase III ASCEND trial that was ongoing at the time of this program.

Patient Population in Real-World Clinical Practice

In this real-world cohort, age, sex, and smoking habits were similar to patient characteristics in ASCEND [11]. However, in the pirfenidone arm of ASCEND, 95.7% of patients had a definite pattern of UIP on HRCT, compared with 69.8% of patients in our study. This is consistent with other real-world evidence suggesting that about half of patients with IPF do not have a definite UIP pattern by HRCT [13].

Notably, in ASCEND [11], 30.9% of patients had a historical surgical lung biopsy, compared with 46% of patients in our study. This difference is likely related to the higher percentage of patients with a definite UIP pattern on HRCT in ASCEND compared with our study.

Some differences in the patient populations between ASCEND [11] and our cohort exist due to real-world patients having co-morbidities such as chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, pulmonary embolism, and pulmonary hypertension, which were mostly excluded from the ASCEND trial. Indeed, strict rules are applied in the selection of patients in clinical trials, while a more pragmatic approach is often adopted in daily clinical practice. As a result, patients treated in a real-world setting typically display less homogenous characteristics and may have more co-morbidities and concomitant medications than those enrolled in clinical trials.

Notably, differences in patient characteristics observed in the real world versus clinical trials often arise due to differences in experience and views across multidisciplinary teams that may impact diagnosis. Indeed, unlike in our study, the ASCEND trial included a central review, which was conducted by reputable radiology and pathology experts, allowing for an integrated approach to diagnosis. A notable gap in the diagnostic proficiencies between community and academic experts has been reported, resulting in recommendations for patients to be referred to centers with expertise in interstitial lung disorders [14].

Longitudinal Changes in Pulmonary Function

Overall, our results suggest that pirfenidone has a favorable effectiveness profile in a patient cohort where a more pragmatic approach in daily practice was undertaken, consistent with the positive effect observed in clinical studies [9, 10, 15, 16]. Additionally, outcomes for patients with data available from 6 months prior to commencing pirfenidone treatment are similar to those recorded in an observational cohort study in Germany, which reported a reduction in mean decline of %FVC after treatment start (0.7 ± 10.9%) compared with the pre-treatment period (6.6 ± 6.7%, p = 0.098) [17]. Similar findings to those presented in the categorical analysis of FVC decline (Fig. 3) were presented by Bonella and colleagues [15].

The proportion of patients in this study who had an FVC decline ≥10% or died by 12 months was comparable with that reported in ASCEND [11]. One limitation of this comparison is that follow-up pulmonary function data for patients who stopped treatment were not available, nor was any imputation performed for missing values. In the ASCEND study, missing values for reasons other than death were imputed as the average value for the three patients with the smallest sum of squared differences in FVC values at the prior visits; this method was not feasible with the relatively limited number of patients in our cohort. Nonetheless, if patients who stopped treatment are excluded from our analysis, the proportion of patients who had a decline of ≥10% predicted FVC or who died at 12 months was 21%, which is comparable to the proportion observed in the ASCEND study.

The 12-month Kaplan–Meier progression-free survival estimate is consistent with that of the alternative non-censored analysis presented in Table 2. However, this estimate cannot be directly compared with that obtained in the ASCEND study where the composite end point additionally included confirmed decrease of 50 m or more in the 6-min walk distance, a parameter that could not be analyzed here owing to a lack of standardized measurement across centers and follow-up data [11].

Considering the increased probability of fatal events as FVC decreases [11, 18], a reduced decline in FVC in real-world practice with pirfenidone is clinically important. Results from du Bois and colleagues [18] demonstrate that FVC is a reliable and valid parameter to assess lung function; a decline in %FVC of ≥10% at 6 months was associated with a nearly fivefold increase in the risk of 1-year mortality, and a decline of 5–10% conferred a more than twofold increased risk of premature death. Moreover, statistical analyses to assess minimal clinically important difference found that small changes in FVC (2–6%) were associated with clinically relevant changes of disease status [18].

In the future, additional validated clinical markers of IPF progression could enable physicians to better define a patient’s condition and the benefits of treatment.

Pirfenidone Safety and Tolerability

The nature of the AEs observed in this analysis was consistent with those seen in Phase III trials [9, 10] and other studies documenting clinical experience with pirfenidone [15, 16]. Nausea was one of the most frequently reported treatment-emergent AEs in the pooled cohort and was also the most prevalent AE in the pirfenidone 2403 mg/day treatment group of the CAPACITY and ASCEND trials [9, 11]. The overall prevalence of AEs across the three centers (57.1% of patients) was lower than that reported in the CAPACITY and ASCEND trials, where nearly all patients reported at least one treatment-emergent AE [11]. This may be due to the fact that the collection and reporting of AEs were less formalized in this clinical practice cohort. It is not clear whether a difference in the prevalence of AEs between the three centers was due to demographic differences or differences in how AEs were reported.

Management of AEs: Experience and Practical Lessons

These data represent our first experiences with prescribing pirfenidone. There was an inevitable learning curve in the management of AEs, which may have led to an elevated number of treatment modifications and/or discontinuations. This would be expected to decrease as physicians become more experienced. As shown recently in the pirfenidone post-authorization safety registry [19], in which adverse drug reactions were managed by dose adjustment, patients with dose adjustments were less likely to discontinue treatment than those without (24.7% vs. 75.3%, p = 0.002) and remained on therapy for a longer period of time. Indeed, dose adjustment may influence the long-term tolerability of pirfenidone.

Sharing different approaches will be key to optimizing treatment compliance and pirfenidone-related AE management. We recommend a flexible, tailor-made approach to dose adjustments based on the severity of observed AEs and responses to changes in dose levels. We also emphasize that physicians prescribing pirfenidone should repeatedly and carefully consider the balance between side effects and the efficacy of pirfenidone in slowing lung function decline [11].

Since there are no general rules as to when patients should be re-challenged following temporary treatment interruption, the decision to re-challenge must be made on an individual basis according to patient needs and AE severity. Adopting the optimal approach for the individual patient would clearly be facilitated by a higher frequency of patient visits. A specialist nurse might also be involved in the follow-up process and provide patient counseling leading to better titration and tolerance of the drug [20].

Patient awareness and expectations regarding pirfenidone therapy and its associated AEs, such as pirfenidone-related skin photosensitivity and GI side effects, is crucial, as preventative measures could be adopted to stop or minimize the severity of these occurrences. To prevent GI side effects, it is advised to take pirfenidone during a meal and to even take the three capsules separately throughout the meal. Dose reduction can also be used to reduce GI side effects. Proton pump inhibitors and prokinetics also seem to reduce GI side effects in clinical experience [21]. Whereas some tolerance may occur with GI side effects, the photosensitivity reaction can occur at any time regardless of the length of therapy, and therefore patients should be vigilant about sun exposure.

In treating patients with IPF, the balance between disease-centered care and palliation should constantly be evaluated. Patient needs should be identified [22, 23] and integrated into better patient-reported outcomes to help health-care professionals optimize patients’ quality of life.

Many of the patients reported in this analysis are still receiving treatment and additional results will be evaluated following longer follow-up periods.

Limitations

The retrospective nature of this analysis limited the clinical parameters which could be meaningfully analyzed. There were no pre-specified protocols for evaluating the 6-min walk test, dyspnea, and acute exacerbations of IPF. Defining and following protocols to rigorously evaluate these parameters is difficult to manage even in prospectively planned multicenter clinical trials [24]. There was also no systematic measurement of these parameters during follow-up. The sporadic data collected for these parameters are not presented.

The results from this cohort reflect daily clinical experience and should be considered instructional. All analyses of pirfenidone effectiveness are exploratory due to their uncontrolled and open nature. Since missing data were not imputed and final analysis was conducted on study completers, inferences derived from these data are vulnerable to selection bias.

Open Questions

The timing of pirfenidone treatment initiation in patients with IPF remains an open question. Many experts in the field are convinced that early treatment is mandatory [25]. Furthermore, it has been shown that FVC decline correlates with an increased risk of mortality [15], suggesting that treatment should be initiated in a timely manner, when lung function is still preserved and before IPF progression accelerates [11].

Conclusions

Data supporting the real-world benefit of pirfenidone use in everyday clinical practice are beginning to emerge and appear to mirror results of large controlled clinical trials. Indeed, in this cohort study, pirfenidone showed a safety and effectiveness profile not dissimilar to that observed in the recently published ASCEND study. These real-world clinical data may help to further educate physicians who lack experience in managing a patient with IPF receiving pirfenidone treatment and, in turn, support better patient outcomes.

References

Collard HR, King TE Jr, Bartelson BB, Vourlekis JS, Schwarz MI, Brown KK. Changes in clinical and physiologic variables predict survival in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2003;168:538–42.

Kim DS, Collard HR, King TE Jr. Classification and natural history of the idiopathic interstitial pneumonias. Proc Am Thorac Soc. 2006;3:285–92.

Meltzer EB, Noble PW. Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2008;3:8–22.

Raghu G, Collard HR, Egan JJ, et al. An official ATS/ERS/JRS/ALAT statement: Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis: evidence-based guidelines for diagnosis and management. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2011;183:788–824.

Navaratnam V, Fleming KM, West J, et al. The rising incidence of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis in the U.K. Thorax. 2011;66:462–7.

Raghu G, Chen SY, Yeh WS, et al. Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis in US Medicare beneficiaries aged 65 years and older: incidence, prevalence, and survival, 2001-11. Lancet Respir Med. 2014;2:566–72.

Nitedanib (Ofev®) FDA news release. http://www.fda.gov/NewsEvents/Newsroom/PressAnnouncements/ucm418994.htm (Accessed February 2015).

Nitedanib (Ofev®) EMA. http://www.ema.europa.eu/ema/index.jsp?curl=pages/medicines/human/medicines/003821/human_med_001834.jsp&mid=WC0b01ac058001d124 (Accessed February 2015).

Noble PW, Albera C, Bradford WZ, et al. Pirfenidone in patients with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (CAPACITY): two randomised trials. Lancet. 2011;377:1760–9.

Taniguchi H, Ebina M, Kondoh Y, et al. Pirfenidone in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Eur Respir J. 2010;35:821–9.

King TE Jr, Bradford WZ, Castro-Bernardini S, et al. A phase 3 trial of pirfenidone in patients with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. N Engl J Med. 2014;370:2083–92.

EMA. Esbriet® (pirfenidone) Summary of product characteristics. http://www.ema.europa.eu/docs/en_GB/document_library/EPAR_-_Summary_for_the_public/human/002154/WC500102979.pdf (Accessed February 2015).

Hunninghake GW, Zimmerman MB, Schwartz DA, et al. Utility of a lung biopsy for the diagnosis of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2001;164:193–6.

Flaherty KR, Andrei AC, King TE Jr, et al. Idiopathic interstitial pneumonia: do community and academic physicians agree on diagnosis? Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2007;175:1054–60.

Bonella F, Wessendorf TE, Costabel U. Clinical experience with pirfenidone for the treatment of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Dtsch Med Wochenschr. 2013;138:518–23.

Okuda R, Hagiwara E, Baba T, Kitamura H, Kato T, Ogura T. Safety and efficacy of pirfenidone in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis in clinical practice. Respir Med. 2013;107:1431–7.

Oltmanns U, Kahn N, Palmowski K, et al. Pirfenidone in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis: real-life experience from a German tertiary referral center for interstitial lung diseases. Respiration. 2014;88:199–207.

du Bois RM, Weycker D, Albera C, et al. Forced vital capacity in patients with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis: test properties and minimal clinically important difference. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2011;184:1382–9.

Koschel D, Cottin V, Skold M, et al. Pirfenidone post-authorization safety registry (PASSPORT)—interim analysis of IPF treatment. Eur Respir J. 2014;44(Suppl. 58):1904.

Chaudhuri N, Duck A, Frank R, Holme J, Leonard C. Real world experiences: pirfenidone is well tolerated in patients with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Respir Med. 2014;108:224–6.

Arai T, Inoue Y, Sasaki Y, et al. Predictors of the clinical effects of pirfenidone on idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Respir Invest. 2014;52:136–43.

Schoenheit G, Becattelli I, Cohen AH. Living with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis: an in-depth qualitative survey of European patients. Chron Respir Dis. 2011;8:225–31.

Swigris JJ, Fairclough D. Patient-reported outcomes in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis research. Chest. 2012;142:291–7.

O’Riordan T, Smith V, Raghu G. Development of novel agents for idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis: progress in target selection and clinical trial design. Chest. 2015. doi:10.1378/chest.14-3218.

Antoniou KM, Wells AU. Acute exacerbations of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Respiration. 2013;86:265–74.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge the invaluable contribution of specialist nurses in caring for the patients with IPF described in this paper, editorial assistance from Fishawack Communications GmbH, a member of the Fishawack group of companies, funded by InterMune International AG and Roche, and statistical support provided by Roche. Article processing charges and the open access charge for this study were funded by Roche. All authors had full access to all of the data in this study and take complete responsibility for the integrity of the data and accuracy of the data analysis. MW, JG, and WW acquired and interpreted the data and wrote the manuscript. All named authors meet the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors (ICMJE) criteria for authorship for this manuscript, take responsibility for the integrity of the work as a whole, and have given final approval to the version to be published.

Conflict of interest

MW has received speaker and advisory board honoraria, paid to her institute, from InterMune, Boehringer Ingelheim, and Roche, and an unrestricted research grant, paid to her institute, from InterMune, outside the submitted work. JG has received speaker and advisory board honoraria from InterMune and Boehringer Ingelheim. WW has received speaker and advisory board honoraria from InterMune, Boehringer Ingelheim, and Roche and grants paid to his institution from InterMune outside the submitted work.

Compliance with ethics guidelines

All procedures followed were in accordance with the ethical standards of the responsible committee on human experimentation (institutional and national) and with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975, as revised in 2000 and 2008. Patient permissions for data collection and usage were granted according to specific local requirements of the medical ethical committee at each participating center. Additional informed consent was obtained from all patients, for which identifying information is included in this article.

Open Access

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and the source are credited.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0), which permits use, duplication, adaptation, distribution, and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Wijsenbeek, M.S., Grutters, J.C. & Wuyts, W.A. Early Experience of Pirfenidone in Daily Clinical Practice in Belgium and The Netherlands: a Retrospective Cohort Analysis. Adv Ther 32, 691–704 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12325-015-0225-1

Received:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12325-015-0225-1