Abstract

Thymoma and thymic carcinoma are thymic epithelial tumors (TETs). We performed a molecular profiling to investigate the pathogenesis of TETs and identify novel targets for therapy. We analyzed 37 thymomas (18 type A, 19 type B3) and 35 thymic carcinomas. The sequencing of 50 genes detected nonsynonymous mutations in 16 carcinomas affecting ALK, ATM, CDKN2A, ERBB4, FGFR3, KIT, NRAS and TP53. Only two B3 thymomas had a mutation in noncoding regions of the SMARCB1 and STK11 gene respectively. Three type A thymomas harbored a nonsynonymous HRAS mutation. Fluorescence in situ hybridization detected in 38 % of carcinomas a CDKN2A, in 32 % a TP53 and in 8 % an ATM gene deletion, whereas only one B3 thymoma exhibited a CDKNA deletion, and none of the type A thymomas showed a gene loss. Sequencing of the total miRNA pool of 5 type A thymomas and 5 thymic carcinomas identified the C19MC miRNA cluster as highly expressed in type A thymomas, but completely silenced in thymic carcinomas. Furthermore, the miRNA cluster C14MC was downregulated in thymic carcinomas. Among non-clustered miRNAs, the upregulation of miR-21, miR-9-3 and miR-375 and the downregulation of miR-34b, miR-34c, miR-130a and miR-195 in thymic carcinomas were most significant. The expression of ALK, HER2, HER3, MET, phospho-mTOR, p16INK4A, PDGFRA, PDGFRB, PD-L1, PTEN and ROS1 was investigated by immunohistochemistry. PDGFRA was increased in thymic carcinomas and PD-L1 in B3 thymomas and thymic carcinomas. In summary, our results reveal genetic differences between thymomas and thymic carcinomas and suggest potential novel targets for therapy.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Thymic epithelial tumors (TETs) are rare mediastinal tumors. The WHO classification distinguishes type A, AB, B1, B2 and B3 thymomas and rare other subtypes from thymic carcinomas [1]. Type A and AB thymomas are mostly benign, whereas type B1, B2 and B3 thymomas are more aggressive, with B3 thymomas having the greatest tendency for mostly intrathoracic spread. Thymic carcinoma on the contrary is a highly aggressive tumor with frequent lymphatic and hematogenous metastasis.

The therapy is based on surgery and in cases of spread or incomplete resection on chemo- and radiotherapy [2]. The development of molecularly targeted drugs has so far been limited by the lack of information on the molecular alterations of TETs and the rarity of the disease. Mutation of the tyrosine kinase KIT was the only known targetable alteration in thymic carcinoma, but it is present in only 6–12 % of cases [3, 4]. Recently, whole exome and targeted gene panel sequencing of TETs identified a specific missense mutation in GTF2I in type A thymomas and common mutations in TP53 and epigenetic regulatory genes in thymic carcinomas [5–8].

We performed a molecular profiling study to derive further insight into the pathogenesis of TETs and to identify potential novel targets for therapy. We focused the analysis on B3 thymomas and thymic carcinomas, because of their aggressiveness and due to the need to improve therapy. The analysis of type A thymomas served for comparison to elucidate molecular alterations that may be associated with aggressivenes. An additional genetic analysis of subtypes AB, B1 and B2 would have been hampered by the abundant presence of normal thymocytes in these subtypes, which impedes mutation detection and miRNA profiling.

We carried out DNA sequencing of type A and B3 thymomas and thymic carcinomas with a panel of 50 genes comprising oncogenes and tumor suppressor genes known to be frequently altered in various tumors. Currently, such gene panels are increasingly utilized in diagnostic molecular pathology for the identification of therapeutic targets in various malignancies. Such a panel sequencing is feasible with formalin fixed, paraffin embedded tissue, which is not well suited for exome sequencing, which in turn requires frozen tissue that is often not available in routine histopathology diagnostics. We complemented the genetic tumor profiling with sequencing the total miRNA pool of 5 type A thymomas and 5 thymic carcinomas for which unfixed, frozen tissue was available. Furthermore, we explored the thymomas and thymic carcinomas with a panel of immunohistochemical stains for antigens (ALK, HER2, HER3, MET, phospho-mTOR, p16INK4A, PDGFRA, PDGFRB, PD-L1, PTEN, and ROS1) that might constitute putative targets for therapy and fluorescence in situ hybridization for ALK, ATM, CDKN2A, FGFR3 and TP53, to detect rearrangements and/or numerical aberrations of these genes.

Materials and Methods

Tissue Samples

Formalin fixed, paraffin embedded type A (n = 18) and B3 (n = 19) thymoma, thymic carcinoma (n = 35; 34 squamous cell carcinomas, 1 lymphoepithelioma-like carcinoma) and non-neoplastic thymus (n = 6) tissues were retrieved from the archive of the Department of Pathology, Medical University Vienna. For miRNA sequencing unfixed frozen tissues of 5 type A thymomas and 5 thymic squamous cell carcinomas stored in liquid nitrogen were utilized. The tumors were diagnosed and subtyped according to the WHO classification [1]. The study was approved by the ethics commitee of the Medical University Vienna (projects 1167/15, 1259/15 and 1794/15).

Cancer Gene Panel Sequencing

DNA was extracted from paraffin embedded tissue blocks with a QIAamp Tissue Kit™ (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany). 10 ng DNA per sample were utilized for sequencing. The DNA library was generated by multiplex polymerase chain reaction (PCR) with the Ion AmpliSeq Cancer Hotspot Panel v2™ (Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA). This panel covers mutation hotspots of 50 genes, mostly oncogenes and tumor suppressor genes that are frequently mutated in tumors. Template preparation was carried out by emulsion PCR with Ion One Touch™ or Ion Chef™ instruments (Life Technologies). Sequencing was performed with an Ion Torrent PGM™ (Life Technologies). Sequencing data were analyzed using Variant Caller™, Ion Reporter™ (both from Life Technologies) and the VARIFI software developed by the Center for Integrative Bioinformatics Vienna. Nonsynonymous mutations detected with the Ion Torrent PGM™ were verified by capillary sequencing. PCR primers flanking the DNA mutation were designed. The DNA was amplified by PCR with Jump Start™ REDtaqR Ready Mix™ (Sigma-Aldrich, Vienna, Austria). PCR products were cleaned using ExoSAP-IT (Affymetrix, Santa Clara, CA). The sequencing of PCR products was carried out with the BigDyeR Terminator v1.1 Cycle Sequencing Kit (Applied Biosystems, Waltham, MA). The resulting DNA fragments were purified with the DyeEx 96 Kit (Qiagen) and sequenced with a 3500 Genetic Analyzer (Applied Biosystems). For sequence analysis we employed the SeqScape Version 2.7 software (Applied Biosystems). In TETs with nonsynonymous mutations detected by panel and capillary sequencing DNA from normal tissue of the patients was also sequenced to exclude rare polymorphisms.

miRNA Sequencing

MiRNA was isolated from unfixed, frozen type A thymoma and thymic carcinoma tissues with a PureLink™ miRNA Isolation Kit (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA). The miRNA concentration was determined using a QubitR microRNA assay kit and a QubitR fluorometer (Thermo Fisher, Waltham, MA). The size distribution of the miRNAs was validated with an Agilent small RNA kit and an Agilent Bioanalyzer instrument (Agilent, Santa Clara, CA). miRNA libraries for sequencing were generated with a Ion Total RNA Seq Kit (Thermo Fisher). Template preparation was achieved with the Ion PGM™ IC 200 Kit on an Ion Chef instrument (Thermo Fisher). Sequencing was performed using the Ion PGM™ Sequencing 200 Kit on an Ion Torrent PGM with Ion 316 chips (Thermo Fisher). An initial adapter trimming of sequencing reads was performed with the Torrent Suite™ software (Thermo Fisher). The sequences were then converted to fastq format and exported for further analysis in the CLC™ Genomics Workbench 8.5 (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany). As recommended by the manufacturer, a second adapter trimming was performed, followed by quality trimming, and mapping to miRBase v21. Quality control of these fastq files was conducted using FastQC. To identify possible RNA degradation, the reads were also mapped against human rRNA and tRNA sequences.

Fluorescence In Situ Hybridization (FISH)

FISH was performed with 4 μm thin sections of type A and B3 thymoma and thymic carcinoma tissue microrrays. The arrays were generated with a manual tissue arrayer from Beecher Instruments (Sun Prairie, WI). Three tissue cores 0.8 mm in diameter each were taken per tumor. The following FISH probes were employed: ALK (2p23.1; Abbott, Abbott Park, IL), ATM (11q22), CDKN2A (9p21)/Centromer 9, FGFR3 (4p16), PTEN (10q23.31)/Centromer 10, TP53 (17p13)/Centromer 17 (Metasystems, Altlussheim, Germany) and ROS1 (Zytovision, Bremerhaven, Germany). 200 cell nuclei per tumor were evaluated. A hetero-/homozygous gene deletion or aneuploidy was concluded when more than 25 % of nuclei showed relevant aberrant fluorescence signals.

Immunohistochemistry

Immunohistochemistry was performed using tissue arrays of type A and B3 thymomas and thymic carcinomas. 2 μm sections of the tissue arrays were stained on a Ventana Benchmark Ultra (Ventana, Tucson, AZ) with extended heat-induced epitope retrieval with CC1 buffer and the ultraView Universal DAB Detection Kit (Ventana). The following antibodies were employed: ALK (clone 1A4; Zytomed, Berlin, Germany), HER2 (clone 4B5; Ventana), HER3 (clone SP71; Abcam, Milton, UK), MET (clone SP44; Ventana), phospho-mTOR (clone 49F9; Cell Signalling, Danvers, MS), p16INK4A (clone E6H4; Ventana), PDGFRA (rabbit polyclonal; Thermo Fisher Scientific), PDGFRB (clone 28E1, Cell Signalling), PD-L1 (clone E1L3N; Cell Signalling), PTEN (clone Y184; Abcam) and ROS1 (clone D4D6; Cell Signalling). An immunohistochemial score was determined by multiplying the percentage of positive cells by their respective staining intensity (0 = negative, 1 = weak, 2 = moderate, 3 = strong). Immunohistochemical score (maximum 300) = (% negative x 0) + (% weak x 1) + (% moderate x 2) + (% strong x 3).

Statistics

MiRNA sequencing data were analyzed in a CLC Genomics Workbench (Qiagen) with an embedded version of EdgeR [9]. To correct for multiple testing, the false discovery rate method (FDR) was used. A FDR below 0.05 was defined as differentially expressed. Graphs, plots and heatmaps were created with Microsoft Excel, CLC Genomics Workbench, and IBM SPSS Statistics 20. Immunohistochemistry results were evaluated employing the Shapiro-Wilk, Kolmogorov-Smirnoff and Kruskal-Wallis tests. Patient survival data were determined using the Kaplan-Meier estimator and significances were calculated by the log-rank and Breslow tests.

Results

Targeted Cancer Gene Sequencing Reveals Genetic Differences Between Thymoma and Thymic Carcinoma and Identifies Potential Novel Targets for Therapy

We sequenced mutation hotspot regions of 50 genes that are known to be frequently mutated in various human cancers. A total of 35 thymic carcinomas, 19 type B3 thymomas and 18 type A thymomas were analyzed. In 16 (46 %) thymic carcinomas a nonsynonymous mutation was detected that is predicted to alter the amino acid sequence of the encoded protein (Tables 1 and 2). The most frequently altered gene was TP53 which was mutated in 9 carcinomas, with one case harboring two TP53 mutations. Four carcinomas exhibited a missense mutation in the tumor suppressor CDKN2A, which was thus the second most frequently mutated gene. Two carcinomas each harbored a missense mutation in the fibroblast growth factor receptor 3 (FGFR3) and the receptor tyrosine kinase KIT. The receptor tyrosine kinases ALK and ERBB4, the serine/threonine kinase ATM, and the GTPase NRAS were mutated in one thymic carcinoma each (Tables 1 and 2).

The B3 thymomas did not harbor any of the mutations detected in thymic carcinomas. Only in two (11 %) B3 thymomas a mutation was detected (Tables 1 and 2). One was a point mutation in the 3′ untranslated region at position −17 of the tumor suppressor SMARCB1. The other represented a deletion of two nucleotides +16 and +17 upstream of the exon-intron boundary of exon 4 of the tumor suppressor STK11. At present it is unknown wether these mutations have any effect on gene function, in particular on RNA translation or RNA splicing.

Three (17 %) of the 18 type A thymomas harbored a non-synonymous mutation in the HRAS oncogene (Tables 1 and 2). One of these thymomas (case 3, Table 2) was a histomorphologically atypical variant type A thymoma [10] with a lung metastasis.

Fluorescence In Situ Hybridization (FISH) - Frequent Loss of CDKN2A and TP53 in Thymic Carcinomas

DNA sequencing revealed TP53 and CDKN2A as the most frequently mutated genes in thymic carcinomas and detected one case of ATM mutation. We therefore performed FISH to determine wether additional deletions of these tumor suppressor genes were present. A total of 28 thymic carcinomas were analyzed for a loss of TP53. Nine (32 %) exhibited a heterozygous or mixed heterozygous/homozygous deletion of TP53 (Table 3). In 4 cases a heterozygous deletion was associated with a mutation of the remaining TP53 allele. Twelve of 32 (38 %) analyzed thymic carcinomas exhibited a loss of the CDKN2A gene, which was heterozygous in three, homozygous in four and mixed heterozygous/homozygous in five cases (Table 3). Cause specific survival, freedom of recurrence, disease free and overall survival of thymic carcinomas with a CDKN2A (Supplementary Fig. S1) or TP53 (Supplementary Fig. S2) gene alteration (mutation and/or deletion) did not differ from wild-type cases. A TP53 gene loss was not present in 17 B3 thymomas analyzed. Only in one of 17 (6 %) B3 thymomas a mixed heterozygous/homozygous CDKN2A gene deletion was detected. In type A thymomas, no TP53 and CDKN2A deletions were present (Table 3). A heterozygous deletion of ATM was noted in two (8 %) of 26 thymic carcinomas. None of them harbored an ATM mutation by gene sequencing. In type A and B3 thymomas no ATM loss was found (Table 3).

Motivated by the two thymic carcinomas with an FGFR3 mutation and the one carcinoma with an ALK mutation, we also performed FISH for these two genes. However a FGFR3 amplification or ALK translocation was not detected in 25 and 27 evaluated thymic carcinomas, respectively (data not shown).

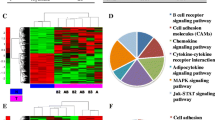

miRNA Sequencing Identifies Differential miRNA Expression in Type A Thymoma and Thymic Carcinoma

The expression of 1218 different miRNAs was detected in type A thymomas and thymic carcinomas. 113 of the miRNAs were differentially expressed between the two tumor entities at a false discovery rate corrected p-value of below 0.05 (Fig. 1). Sixtythree of these 113 miRNAs were part of two large imprinted miRNA clusters on chr19q13.4 and chr14q32, called C19MC and C14MC, respectively. C19MC miRNAs were highly expressed in 4 of the 5 type A thymomas and completely silenced in all 5 thymic carcinomas (Fig. 2). C14MC transcripts were also significantly downregulated in thymic carcinomas, but the cluster was not completely silenced (Fig. 3). Fifty of the differentially expressed miRNAs were not clustered. Amongst them, most significant was the strong expression of miR21, miR-9-3 and miR-375 in thymic carcinomas and their very low abundance in type A thymomas (Fig. 4). On the contrary miR-34b, miR-34c, miR-130a and miR-195 were of low abundance in thymic carcinomas, but strongly expressed in type A thymomas (Fig. 5).

Immunhistology Identifies PDGFRA and PD-L1 as Potential Therapeutic Targets in Thymic Carcinoma and B3 Thymoma

Type A and B3 thymoma and thymic carcinoma tissues were stained with antibodies to ALK, HER2, HER3, MET, phospho-mTOR, PDGFRA, PDGFRB, PD-L1, p16INK4A, PTEN and ROS1 to identify potential targets for therapy.

The tumor cells did not express ALK, HER2, and HER3 (Table 4).

A weak MET expression was noted in only two (13 %) of 15 type A thymomas. B3 thymomas and thymic carcinomas did not express MET.

The expression of phospho-mTOR was similar in type A and B3 thymomas and thymic carcinomas (Table 4).

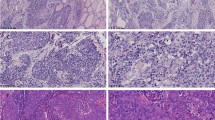

The expression of PDGFRA was significantly increased in thymic carcinomas as compared to type A and B3 thymomas (Table 4, Fig. 6, Supplementary Fig. S3). A low PDGFRB expression was noted in 40 % of type A and 12 % of B3 thymomas. Thymic carcinomas were PDGFRB negative (Table 4).

The immune check point inhibitor PD-L1 was expressed in only 2 (13 %) of 15 type A thymomas, but 13 (76 %) of 17 B3 thymomas and 16 (53 %) of 30 thymic carcinomas (Table 4, Fig. 7, Supplementary Fig. S4). The expression of PD-L1 in thymic carcinomas did not correlate with a difference in cause specific survival, freedom of recurrence, disease free and overall survival (Supplementary Fig. S5).

In six non-neoplastic thymi of adult individuals, analyzed for comparison with TETs, p16INK4A expressing epithelial cells were scarce and located in close vicinity to Hassall’s corpuscles (data not shown). In TETs, 10 (67 %) of 15 type A thymomas and 14 (47 %) of 30 thymic carcinomas expressed p16INK4A, wheras only one of 17 (6 %) B3 thymomas exhibited a low p16INK4A positivity (Table 4, Fig. 8). In thymic carcinomas, but not in type A and B3 thymomas, a lack of p16INK4A expression was largely associated with CDKN2A mutation or gene deletion (data not shown). The expression of p16INK4A did not correlate with a difference in cause specific survival, freedom of recurrence, disease free and overall survival in thymic carcinomas (Supplementary Fig. S6).

The expression of PTEN was heterogenous, with no significant differences between the three tumor entities (Table 4). A lack of PTEN expression was noted in one B3 thymoma and one thymic carcinoma. However, both tumors retained two PTEN signals as assessed by FISH (data not shown). Thus, the lack of PTEN expression was not caused by gene deletion, but by another mechanism, presumably PTEN promoter methylation.

A low ROS1 expression was present in 3 (20 %) of 15 type A thymomas, but none of them harbored a ROS1 gene translocation as assessed by FISH (data not shown). B3 thymomas and thymic carcinomas were ROS1 negative (Table 4).

Discussion

By gene panel and miRNA sequencing, FISH and immunohistochemistry we found genetic differences between thymoma (type A and B3) and thymic carcinoma and identified potential novel targets for therapy.

The most frequently altered gene was the tumor suppressor CDKN2A. It encodes p16INK4A and p14ARF by alternative splicing. p16INK4A inhibits cell cycle progression by blocking cyclin dependent kinases 4 and 6, whereas p14ARF activates the TP53 tumor suppressor. A CDKN2A alteration may lead to activation of cyclin dependent kinases. Inhibitors for these kinases are currently being investigated in clinical trials for various malignancies and might constitute a therapeutic option also for thymic carcinomas [11]. In a previous work by Petrini I. et al. a lack of p16INK4A protein expression identified TETs with a worse disease related survival [12]. In our study, however, CDKN2A gene loss or mutation did not correlate with a worse outcome in thymic carcinomas.

The second most frequently altered gene in thymic carcinomas was the tumor suppressor TP53. A TP53 protein overexpression, which is often caused by TP53 mutation, has been reported in a cohort of 25 thymic carcinomas to be associated with a worse disease free survival [7]. In our study with 31 evaluable thymic carcinomas TP53 gene loss or mutation was, however, not a prognostic marker for disease free or overall survival.

The tyrosine kinase KIT is the receptor for stem cell factor. It contributes to the growth and survival of tumors and is best known for its involvement in the pathogenesis of gastrointestinal stromal tumors [13]. Mutated KIT constitutes a therapeutic target for kinase inhibitors such as imatinib. KIT mutation is rare in thymic carcinoma, but so far the only known molecular target based on few, but encouraging case reports [14, 15]. In our series two carcinomas with KIT mutations that predict sensitivity to imatinib were present.

The FGFR family includes four receptor tyrosine kinases. FGFR genes are deregulated in solid tumors by amplification, translocation or mutation [16]. FGFR3 mutations are particulary frequent in bladder cancer, where they are associated with low grade, early stage, and better survival [17]. We observed a FGFR3 missense mutation in two thymic carcinomas. Thus, inhibition of FGFR3 might represent a novel target in a subset of thymic carcinomas. Several FGFR inhibitors are currently in development and being evaluated in clinical trials [16, 18].

ALK is a receptor tyrosine kinase that, when altered by chromosomal inversion, translocation, amplification or mutation, plays an oncogenic role in certain cancers. Best known are ALK gene alterations in anaplastic large cell lymphoma, lung adenocarcinoma, inflammatory myofibroblastic tumor and neuroblastoma [19]. The p.R1275Q ALK mutation observed in one of our thymic carcinomas is an activating point mutation in the kinase domain and known as one of the most common mutations in neuroblastoma [20]. We did not detect an ALK rearrangement or amplification in TETs by FISH. An ALK mutation had also been detected by Petrini I. et al. in an AB and a B3 thymoma by exome and panel sequencing [5]. Small molecule inhibitors such as crizotinib, that target the kinase activity of ALK, are established in the clinic and might be a novel therapeutic in ALK mutated TETs as well.

The epidermal growth factor receptor family includes EGFR, ERBB2 (also known as HER2), ERBB3 (also known as HER3) and ERBB4. Therapy of colon and breast cancer with anti-EGFR and anti-ERBB2 antibodies, respectively, and of EGFR mutated lung adenocarcinoma with tyrosine kinase inhibitors is well established [21]. ERBB4 mutations have been identified in lung, breast and gastric cancer and melanoma. Several of these ERBB4 mutations were shown to be oncogenic in melanoma models and could be inhibited by treatment with lapatinib [22]. ERBB4 mutated thymic carcinoma might also be inhibited by EGFR family blockers such as lapatinib and afatinib [21].

ATM is a kinase which induces cell cycle arrest and facilitates DNA repair. The inhibition of DNA repair has become an attractive strategy in cancer therapy. Small molecule inhibitors of ATM are currently in preclinical and clinical development. They may enhance susceptibility of cancer cells to DNA damaging chemotherapy. Many tumors acquire defects in DNA damage repair in order to tolerate genomic instability which is a characteristic of malignant transformation. Defects in ATM signaling are synthetically lethal with PARP inhibition, suggesting that combined inhibition of ATM and PARP may be a therapeutic strategy [23]. PARP inhibitors are extremely efficient against cancer cells bearing ATM defects, as shown in the context of mantle cell lymphoma [24, 25].

One thymic carcinoma harbored a NRAS and three type A thymomas a HRAS mutation. HRAS was the only mutated gene in type A thymomas in this study. One of the HRAS mutated cases was a histomorphologically atypical variant [10] with a lung metastasis. At present the RAS oncogenes are still not drugable targets, although multiple clinical trials targeting RAS interacting molecules or downstream signaling partners are ongoing [26, 27].

We have identified 113 miRNAs that are differently expessed in type A thymomas and thymic carcinomas. Thereov, 63 miRNAs belong to two large imprinted miRNA clusters, namely C19MC on chromosome 19q13.42 [28] and C14MC on chromosome 14q32 [29]. C19MC overexpression has been reported in embryonal pediatric brain tumors caused by fusion with TTYH1 [30] or focal genomic amplification [31]. Overexpression of this cluster is furthermore observed in thyroid and parathyroid adenomas, hepatic mesenchymal hamartomas, hepatocellular carcinomas and a subset of tamoxifen resistant breast cancers [32–35]. C19MC overexpression in type A and AB thymomas has recently been reported by Radovich M. et al., who suggested that one of the key functions of the cluster is the activation of the PI3K/AKT pathway [36]. However, a report by Ucar et al. [37] indicates that C19MC is also expressed in normal medullary and cortical thymic epithelial cells. Thus, both of the putative progenitor cell types of TETs express C19MC. We therefore propose that C19MC expression is silenced in thymic carcinomas. This may be caused by promoter methylation [28].

C14MC miRNA expression was decreased in thymic carcinomas as compared to type A thymomas, but still present to some degree, with not all miRNAs of the cluster affected. Infering from published work suggesting that C14MC functions as a large tumor suppressor cluster in GIST [38] and glioma [39] we assume that the downregulation of C14MC miRNAs might exert a tumor promoting effect in thymic carcinomas.

Among the non-clustered miRNAs with significant differences in expression between type A thymomas and thymic carcinomas, the low expression of miR-34b, miR-34c, miR-130a and miR-195 in thymic carcinomas was most pronounced. These four miRNAs are putative tumor suppressors. In non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) immune evasion of the tumor via PD-L1 is mediated by miR-34 [40]. A more frequent PD-L1 protein expression in thymic carcinomas as compared to type A thymomas has been observed in our study and might likewise be regulated by miR-34. miR-130a downregulation in hepatocellular carcinoma correlates with poor prognosis [41]. miR-195 prevents cell proliferation and promotes apoptosis by targeting Cyclin D1 and BCL2 and is decreased in many solid tumors [42, 43].

Among the non-clustered miRNAs overexpressed in thymic carcinoma as compared to type A thymoma miR21, miR-9-3 and miR-375 were most significant. miR21 is regarded to be oncogenic. It is upregulated in various solid tumors, lymphomas and leukemias [44, 45]. In contrast to our findings in thymic carcinomas miR-9-3 has been reported to be repressed by methylation in NSCLC [46]. miR-375 was first identified as a pancreatic islet-specific miRNA that regulated insulin secretion [47]. In malignant tumors it is often downregulated and might constitute a tumor suppressor. In breast and prostate cancer, however, it is upregulated [48]. Thus, depending on the cellular context it may exert an oncogenic influence, probably also in thymic carcinomas.

Immunohistochemistry was performed to study the expression of ALK, HER2, HER3, MET, phospho-mTOR, p16INK4A, PDGFRA, PDGFRB, PD-L1, PTEN and ROS1 in type A and B3 thymomas and thymic carcinomas. None of the thymomas and thymic carcinomas analyzed expressed ALK, HER2 and HER3. The lack of HER2 and HER3 expression in our samples is in contrast to previous publications. Weissferdt A. et al. reported HER2 expression in 58 % of 24 squamous thymic carcinomas. Only a single case showed HER2 gene amplification by FISH [49]. The authors furthermore described HER3 positivity in 45.8 % of the carcinomas. Pan CC. et al. detected HER2 positivity in nine of 17 thymic carcinomas, but no HER2 gene amplification could be demonstrated by FISH [50]. The reason for these discrepancies in HER2 and HER3 immunohistochemistry is not known, but might be attributable to the use of different antibodies and staining protocols. As can be seen at least from our study HER2 and HER3 do not constitute a therapeutic target in type A and B3 thymomas and thymic carcinomas.

The proto-oncogene MET is a receptor tyrosine kinase that can promote tumor development and progression. Tumors with MET overexpression, gene amplification and exon 14 skipping mutations are candidates for MET targeted therapies in clinical trials [51, 52]. A low MET protein expression was noted in only two type A thymomas, whereas B3 thymomas and thymic carcinomas did not express MET. Thus, MET does not represent a potential therapeutic target in TETs.

Aberrations in the PI3K/mTOR/AKT pathway are common in solid tumors [53]. Drugs have been developed that target different components of this pathway. We did not detect mutations in PIK3CA and AKT1 in type A and B3 thymomas or thymic carcinomas. Furthermore, the expression of phospho-mTOR protein did not differ significantly among type A and B3 thymomas and thymic carcinomas.

PDGFRA was expressed by medullary epithelial cells of fetal and postnatal normal thymus and by epithelial tumor cells in 10 analyzed thymomas [54]. A further study [55] reported PDGFRA protein expression in all 26 thymomas of various subtypes and 10 thymic carcinomas analyzed. PDGFRB protein was present in only one third of the tumors, however, it was not specified whether epithelial cells or stromal cells were positive [55]. In our study the expression of PDGFRA was increased in thymic carcinomas as compared to type A and B3 thymomas. The PDGFRA gene, however, was not mutated. A weak PDGFRB positivity was present in a few type A and B3 thymomas, whereas all thymic carcinomas were negative. An efficacy of the multi-target tyrosine kinase inhibitors sorafenib and sunitinib that block also PDGFRA has been observed in thymic carcinomas [56, 57]. However, the expression of PDGFRA has not been determined by immunohistochemistry in these studies and it is therefore not possible to conclude whether the efficacy of the drugs was due to PDGFRA inhibition or blockade of other kinases.

The expression of p16INK4A protein in normal tissue is generally low. In non-neoplastic thymic tissues we have observed sparce p16iNK4A positive epithelial cells in the vicinity of Hassall’s corpuscles. In neoplastic cells oncogenic stress can induce p16INK4A. Furthermore, tumors with loss of the RB gene or RB protein inactivation by viral oncogenic proteins harbor high levels of p16INK4A [58]. Ten (67 %) of 15 type A thymomas and 14 (47 %) of 30 thymic carcinomas expressed p16INK4A, whereas only one (6 %) of 17 B3 thymomas was weakly p16INK4A positive. In thymic carcinomas a lack of p16INK4A protein expression was largely associated with CDKNA gene deletion. In type A thymomas that lacked CDKN2A deletions and type B3 thymomas that rarely (7 %) exhibited CDKN2A deletion a different mechanism must predominate. CDKN2A promoter methylation is a known alternative mechanism of p16I INK4A silencing and may dominate in type A and B3 thymomas.

PD-L1 is a molecule that binds to its receptor PD1, which is expressed on cytotoxic T-cells and exerts an inhibitory effect [59, 60]. PD-L1 is produced by a fraction of tumors of different entities and facilitates their immune escape [59, 60]. The blockade of the PD-L1/PD-1 interaction with anti-PD1 and anti-PD-L1 antibodies is a novel therapy with impressive results in various tumor entities [61]. In our study PD-L1 was expressed by only 13 % of type A thymomas, but 76 % of B3 thymomas and 53 % of thymic carcinomas. In contrast, a previous report by Padda et al. [62] that used a different anti-PD-L1 antibody, described PD-L1 expression in all cases of TETs. Furthermore, PD-L1 high TETs were associated with a more aggressive histology and worse prognosis. However, we did not observe a difference in survival between PD-L1 positive and negative thymic carcinomas. A lack of a difference in survival between PD-L1 positive and negative TETs has also been described by Katsuya et al. [63] Considering the correlation of PD-L1 expression by tumor cells with the likelihood of response to anti-PD-1/PD-L1 therapy [64], immune checkpoint inhibitors might be a novel treatment option for unresectable or relapsed thymomas and thymic carcinomas.

The expression of PTEN, a phosphatase that negatively regulates intracellular levels of phosphatidylinositol-3,4,5-trisphosphate and functions as a tumor suppressor by negatively regulating AKT/mTOR signaling pathways [65], was heterogenous, with no significant differences between type A and B3 thymomas and thymic carcinomas. A lack of PTEN expression was noted in only one B3 thymoma and one thymic carcinoma. However, both tumors retained two PTEN signals as assesed by FISH. Thus, the lack of PTEN expression may be caused by an alternative mechanism, like PTEN promoter methylation [66].

ROS1 is a tyrosine kinase that is aberrantly activated by translocation in a subset of lung carcinomas and cholangiocarcinomas. ROS1 translocated tumors frequently respond to therapy with crizotinib [67]. ROS1 positivity by immunohistochemistry is a surrogate marker for the presence of a ROS1 translocation. A weak ROS1 reactivity by immunohistochemistry was noted in three (20 %) type A thymomas, however, they did not harbor a ROS1 translocation as assessed by FISH. Type B3 thymomas and thymic carcinomas did not express ROS1. Therefore, ROS1 does not represent a therapeutic target in TETs.

In summary, our data show genetic differences between type A and B3 thymomas and thymic carcinomas with respect to cancer gene mutations and miRNA expression. The study furthermore demonstrates that next-generation gene panel sequencing of paraffin embedded tissue, which currently enters diagnostic pathology, combined with FISH and immunohistochemistry can identify potential novel therapeutic targets for TETs.

References

Travis WD, Brambilla E, Burke AP, Marx A, Nicholson AG (Eds.) (2015) WHO classification of tumours of the lung, pleura, thymus and heart. IARC Press, Lyon

Kelly RJ, Petrini I, Rajan A, Wang Y, Giaccone G (2011) Thymic malignancies: from clinical management to targeted therapies. J Clin Oncol: Off J Am Soc Clin Oncol 29(36):4820–4827. doi:10.1200/Jco.2011.36.0487

Schirosi L, Nannini N, Nicoli D, Cavazza A, Valli R, Buti S, Garagnani L, Sartori G, Calabrese F, Marchetti A, Buttitta F, Felicioni L, Migaldi M, Rea F, Di Chiara F, Mengoli M, Rossi G (2012) Activating c-KIT mutations in a subset of thymic carcinoma and response to different c-KIT inhibitors. Ann Oncol: Off J Eur Soc Med Oncol / ESMO 23(9):2409–2414.doi:10.1093/Annonc/Mdr626

Yoh K, Nishiwaki Y, Ishii G, Goto K, Kubota K, Ohmatsu H, Niho S, Nagai K, Saijo N (2008) Mutational status of EGFR and KIT in thymoma and thymic carcinoma. Lung Cancer 62(3):316–320

Petrini I, Meltzer PS, Kim IK, Lucchi M, Park KS, Fontanini G, Gao J, Zucali PA, Calabrese F, Favaretto A, Rea F, Rodriguez-Canales J, Walker Rl, Pineda M, Zhu YJ, Lau C, Killian KJ, Bilke S, Voeller D, Dakshanamurthy S, Wang Y, Giaccone G (2014) A specific missense mutation in GTF2I occurs at high frequency in thymic epithelial tumors. Nat Genet 46 (8):844–849. doi:10.1038/Ng.3016. http://Www.Nature.Com/Ng/Journal/V46/N8/Abs/Ng.3016.Html-Supplementary-Information

Wang Y, Thomas A, Lau C, Rajan A, Zhu Y, Killian JK, Petrini I, Pham T, Morrow B, Zhong X, Meltzer PS, Giaccone G (2014) Mutations of epigenetic regulatory genes are common in thymic carcinomas. Sci Rep 4:7336. doi:10.1038/Srep07336

Moreira AL, Won HH, McMillan R, Huang J, Riely GJ, Ladanyi M, Berger MF (2015) Massively parallel sequencing identifies recurrent mutations in TP53 in thymic carcinoma associated with poor prognosis. J Thorac Oncol: Off Publ Int Assoc Study Lung Cancer 10(2):373–380. doi:10.1097/Jto.0000000000000397

Shitara M, Okuda K, Suzuki A, Tatematsu T, Hikosaka Y, Moriyama S, Sasaki H, Fujii Y, Yano M (2014) Genetic profiling of thymic carcinoma using targeted next-generation sequencing. Lung Cancer 86(2):174–179. doi:10.1016/J.Lungcan.2014.08.020

Robinson MD, McCarthy DJ, Smyth GK (2010) edgeR: a Bioconductor package for differential expression analysis of digital gene expression data. Bioinformatics 26(1):139–140. doi:10.1093/Bioinformatics/Btp616

Nonaka D, Rosai J (2012) Is there a spectrum of cytologic atypia in type A thymomas analogous to that seen in type B thymomas? A pilot study of 13 cases. Am J Surg Pathol 36(6):889–894. doi:10.1097/Pas.0b013e31824fff50

Musgrove EA, Caldon CE, Barraclough J, Stone A, Sutherland RL (2011) Cyclin D as a therapeutic target in cancer. Nat Rev Cancer 11(8):558–572. doi:10.1038/Nrc3090

Petrini I, Meltzer PS, Zucali PA, Luo J, Lee C, Santoro A, Lee HS, Killian KJ, Wang Y, Tsokos M, Roncalli M, Steinberg SM, Wang Y, Giaccone G (2012) Copy number aberrations of BCL2 and CDKN2A/B identified by array-CGH in thymic epithelial tumors. Cell Death Dis 3:E351. http://Www.Nature.Com/Cddis/Journal/V3/N7/Suppinfo/Cddis201292s1.Html

Yamamoto H, Oda Y (2015) Gastrointestinal stromal tumor: recent advances in pathology and genetics. Pathol Int 65(1):9–18. doi:10.1111/Pin.12230

Ströbel P, Hartmann M, Jakob A, Mikesch K, Brink I, Dirnhofer S, Marx A (2004) Thymic carcinoma with overexpression of mutated KIT and the response to imatinib. N Engl J Med 350(25):2625–2626. doi:10.1056/Nejm200406173502523

Bisagni G, Rossi G, Cavazza A, Sartori G, Gardini G, Boni C (2009) Long lasting response to the multikinase inhibitor bay 43-9006 (Sorafenib) in a heavily pretreated metastatic thymic carcinoma. J Thorac Oncol: Off Publ Int Assoc Study Lung Cancer 4(6):773–775. doi:10.1097/Jto.0b013e3181a52e25

Dienstmann R, Rodon J, Prat A, Perez-Garcia J, Adamo B, Felip E, Cortes J, Iafrate AJ, Nuciforo P, Tabernero J (2014) Genomic aberrations in the FGFR pathway: opportunities for targeted therapies in solid tumors. Ann Oncol: Off J Eur Soc Med Oncol / ESMO 25(3):552–563. doi:10.1093/Annonc/Mdt419

Liu X, Zhang W, Geng D, He J, Zhao Y, Yu L (2014) Clinical significance of fibroblast growth factor receptor-3 mutations in bladder cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Genet Mol Res: Gmr 13(1):1109–1120. doi:10.4238/2014.February.20.12

Ho HK, Yeo AH, Kang TS, Chua BT (2014) Current strategies for inhibiting FGFR activities in clinical applications: opportunities, challenges and toxicological considerations. Drug Discov Today 19(1):51–62. doi:10.1016/J.Drudis.2013.07.021

Hallberg B, Palmer RH (2013) Mechanistic insight into ALK receptor tyrosine kinase in human cancer biology. Nat Rev Cancer 13(10):685–700. doi:10.1038/Nrc3580

Epstein LF, Chen H, Emkey R, Whittington DA (2012) The R1275Q neuroblastoma mutant and certain ATP-competitive inhibitors stabilize alternative activation loop conformations of anaplastic lymphoma kinase. J Biol Chem 287(44):37447–37457. doi:10.1074/Jbc.M112.391425

Modjtahedi H, Cho BC, Michel MC, Solca F (2014) A comprehensive review of the preclinical efficacy profile of the ErbB family blocker afatinib in cancer. Naunyn Schmiedeberg’s Arch Pharmacol 387(6):505–521. doi:10.1007/S00210-014-0967-3

Prickett TD, Agrawal NS, Wei X, Yates KE, Lin JC, Wunderlich JR, Cronin JC, Cruz P, Rosenberg SA, Samuels Y (2009) Analysis of the tyrosine kinome in melanoma reveals recurrent mutations in ERBB4. Nat Genet 41(10):1127–1132. doi:10.1038/Ng.438

Michels J, Vitale I, Saparbaev M, Castedo M, Kroemer G (2014) Predictive biomarkers for cancer therapy with PARP inhibitors. Oncogene 33(30):3894–3907. doi:10.1038/Onc.2013.352

Williamson CT, Muzik H, Turhan AG, Zamo A, O’Connor MJ, Bebb DG, Lees-Miller SP (2010) ATM deficiency sensitizes mantle cell lymphoma cells to poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase-1 inhibitors. Mol Cancer Ther 9(2):347–357. doi:10.1158/1535-7163.Mct-09-0872

Weston VJ, Oldreive CE, Skowronska A, Oscier DG, Pratt G, Dyer MJ, Smith G, Powell JE, Rudzki Z, Kearns P, Moss PA, Taylor AM, Stankovic T (2010) The PARP inhibitor olaparib induces significant killing of ATM-deficient lymphoid tumor cells in vitro and in vivo. Blood 116(22):4578–4587. doi:10.1182/Blood-2010-01-265769

Stephen AG, Esposito D, Bagni RR, McCormick F (2014) Dragging ras back in the ring. Cancer Cell 25(3):272–281. doi:10.1016/J.Ccr.2014.02.017

Singh H, Longo DL, Chabner BA (2015) Improving prospects for targeting RAS. J Clin Oncol: Off J Am Soc Clin Oncol 33(31):3650–3659. doi:10.1200/Jco.2015.62.1052

Noguer-Dance M, Abu-Amero S, Al-Khtib M, Lefevre A, Coullin P, Moore GE, Cavaille J (2010) The primate-specific microRNA gene cluster (C19MC) is imprinted in the placenta. Hum Mol Genet 19(18):3566–3582. doi:10.1093/Hmg/Ddq272

Morales-Prieto DM, Ospina-Prieto S, Chaiwangyen W, Schoenleben M, Markert UR (2013) Pregnancy-associated miRNA-clusters. J Reprod Immunol 97(1):51–61. doi:10.1016/J.Jri.2012.11.001

Kleinman CL, Gerges N, Papillon-Cavanagh S, Sin-Chan P, Pramatarova A, Quang DAK, Adoue V, Busche S, Caron M, Djambazian H, Bemmo A, Fontebasso AM, Spence T, Schwartzentruber J, Albrecht S, Hauser P, Garami M, Klekner A, Bognar L, Montes JL, Staffa A, Montpetit A, Berube P, Zakrzewska M, Zakrzewski K, Liberski PP, Dong Z, Siegel PM, Duchaine T, Perotti C, Fleming A, Faury D, Remke M, Gallo M, Dirks P, Taylor MD, Sladek R, Pastinen T, Chan JA, Huang A, Majewski J, Jabado N (2014) Fusion of TTYH1 with the C19MC microRNA cluster drives expression of a brain-specific DNMT3B isoform in the embryonal brain tumor ETMR. Nat Genet 46 (1):39–44. doi:10.1038/Ng.2849. http://Www.Nature.Com/Ng/Journal/V46/N1/Abs/Ng.2849.Html-Supplementary-Information

Korshunov A, Remke M, Gessi M, Ryzhova M, Hielscher T, Witt H, Tobias V, Buccoliero AM, Sardi I, Gardiman MP, Bonnin J, Scheithauer B, Kulozik AE, Witt O, Mork S, Von Deimling A, Wiestler OD, Giangaspero F, Rosenblum M, Pietsch T, Lichter P, Pfister SM (2010) Focal genomic amplification at 19q13.42 comprises a powerful diagnostic marker for embryonal tumors with ependymoblastic rosettes. Acta Neuropathol 120(2):253–260. doi:10.1007/S00401-010-0688-8

Cairo S, Wang Y, De Reynies A, Duroure K, Dahan J, Redon MJ, Fabre M, McClelland M, Wang XW, Croce CM, Buendia MA (2010) Stem cell-like micro-RNA signature driven by Myc in aggressive liver cancer. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 107(47):20471–20476. doi:10.1073/Pnas.1009009107

Flor I, Bullerdiek J (2012) The dark side of a success story: microRNAs of the C19MC cluster in human tumours. J Pathol 227(3):270–274. doi:10.1002/Path.4014

Rippe V, Dittberner L, Lorenz VN, Drieschner N, Nimzyk R, Sendt W, Junker K, Belge G, Bullerdiek J (2010) The two stem cell microRNA gene clusters C19MC and miR-371-3 are activated by specific chromosomal rearrangements in a subgroup of thyroid adenomas. PLoS One 5(3), E9485. doi:10.1371/Journal.Pone.0009485

Vaira V, Elli F, Forno I, Guarnieri V, Verdelli C, Ferrero S, Scillitani A, Vicentini L, Cetani F, Mantovani G, Spada A, Bosari S, Corbetta S (2012) The microRNA cluster C19MC is deregulated in parathyroid tumours. J Mol Endocrinol 49(2):115–124. doi:10.1530/Jme-11-0189

Radovich M, Solzak JP, Hancock BA, Conces ML, Atale R, Porter RR, Zhu J, Glasscock J, Kesler KA, Badve SS, Schneider BP, Loehrer PJ (2016) A large microRNA cluster on chromosome 19 is a transcriptional hallmark of WHO type A and AB thymomas. Br J Cancer 114(4):477–484. doi:10.1038/Bjc.2015.425

Ucar O, Tykocinski LO, Dooley J, Liston A, Kyewski B (2013) An evolutionarily conserved mutual interdependence between Aire and microRNAs in promiscuous gene expression. Eur J Immunol 43(7):1769–1778. doi:10.1002/Eji.201343343

Haller F, Von Heydebreck A, Zhang JD, Gunawan B, Langer C, Ramadori G, Wiemann S, Sahin O (2010) Localization-and mutation-dependent microRNA (miRNA) expression signatures in gastrointestinal stromal tumours (GISTs), with a cluster of co-expressed miRNAs located at 14q32.31. J Pathol 220(1):71–86. doi:10.1002/Path.2610

Lavon I, Zrihan D, Granit A, Einstein O, Fainstein N, Cohen M, Cohen M, Zelikovitch B, Shoshan Y, Spektor S, Reubinoff BE, Felig Y, Gerlitz O, Ben-Hur T, Smith Y, Siegal T (2010) Gliomas display a microRNA expression profile reminiscent of neural precursor cells. Neuro-Oncology 12(5):422–433. doi:10.1093/Neuonc/Nop061

Cortez MA, Ivan C, Valdecanas D, Wang X, Peltier HJ, Ye Y, Araujo L, Carbone DP, Shilo K, Giri DK, Kelnar K, Martin D, Komaki R, Gomez DR, Krishnan S, Calin GA, Bader AG, Welsh JW (2016) PDL1 Regulation by p53 via miR-34. J Natl Cancer Inst 108(1). doi:10.1093/Jnci/Djv303

Li B, Huang P, Qiu J, Liao Y, Hong J, Yuan Y (2014) MicroRNA-130a is down-regulated in hepatocellular carcinoma and associates with poor prognosis. Med Oncol 31(10):230. doi:10.1007/S12032-014-0230-2

Jia LF, Wei SB, Gong K, Gan YH, Yu GY (2013) Prognostic implications of micoRNA miR-195 expression in human tongue squamous cell carcinoma. PLoS One 8(2), E56634. doi:10.1371/Journal.Pone.0056634

Liu L, Chen L, Xu Y, Li R, Du X (2010) MicroRNA-195 promotes apoptosis and suppresses tumorigenicity of human colorectal cancer cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 400(2):236–240. doi:10.1016/J.Bbrc.2010.08.046

Krichevsky AM, Gabriely G (2009) miR-21: a small multi-faceted RNA. J Cell Mol Med 13(1):39–53. doi:10.1111/J.1582-4934.2008.00556.X

Shen L, Wan Z, Ma Y, Wu L, Liu F, Zang H, Xin S (2015) The clinical utility of microRNA-21 as novel biomarker for diagnosing human cancers. Tumour Biol: J Int Soc Oncodevelop Biol Med 36(3):1993–2005. doi:10.1007/S13277-014-2806-Z

Heller G, Weinzierl M, Noll C, Babinsky V, Ziegler B, Altenberger C, Minichsdorfer C, Lang G, Döme B, End-Pfützenreuter A, Arns BM, Grin Y, Klepetko W, Zielinski C, Zöchbauer-Müller S (2012) Genome-wide miRNA expression profiling identifies miR-9-3 and miR-193a as targets for DNA methylation in non-small cell lung cancers. Clin Cancer Res: Off J Am Assoc Cancer Res 18(6):1619–1629. doi:10.1158/1078-0432.Ccr-11-2450

Poy MN, Eliasson L, Krutzfeldt J, Kuwajima S, Ma X, MacDonald PE, Pfeffer S, Tuschl T, Rajewsky N, Rorsman P, Stoffel M (2004) A pancreatic islet-specific microRNA regulates insulin secretion. Nature 432(7014):226–230. doi:10.1038/Nature03076

Yan JW, Lin JS, He XX (2014) The emerging role of miR-375 in cancer. Int J Cancer 135 (5):1011–1018. doi:10.1002/ijc.28563

Weissferdt A, Lin H, Woods D, Tang X, Fujimoto J, Wistuba II, Moran CA (2012) HER family receptor and ligand status in thymic carcinoma. Lung Cancer 77(3):515–521. doi:10.1016/J.Lungcan.2012.05.108

Pan CC, Chen PCH, Wang LS, Lee JY, Chiang H (2003) Expression of apoptosis-related markers and HER-2/neu in thymic epithelial tumours. Histopathology 43(2):165–172

Zhang Y, Du Z, Zhang M (2016) Biomarker development in MET-targeted therapy. Oncotarget 7(24):37370–37389 doi:10.18632/Oncotarget.8276

Awad MM, Oxnard GR, Jackman DM, Savukoski DO, Hall D, Shivdasani P, Heng JC, Dahlberg SE, Janne PA, Verma S, Christensen J, Hammerman PS, Sholl LM (2016) MET exon 14 mutations in non-small-cell lung cancer are associated with advanced age and stage-dependent MET genomic amplification and c-MET overexpression. J Clin Oncol: Off J Am Soc Clin Oncol 34(7):721–730. doi:10.1200/Jco.2015.63.4600

Xu K, Liu P, Wei W (2014) mTOR signaling in tumorigenesis. Biochimica Et Biophysica Acta 1846(2):638–654. doi:10.1016/J.Bbcan.2014.10.007

Cimpean AM, Ceausu R, Encica S, Gaje PN, Ribatti D, Raica M (2011) Platelet-derived growth factor and platelet-derived growth factor receptor-alpha expression in the normal human thymus and thymoma. Int J Exp Pathol 92(5):340–344. doi:10.1111/J.1365-2613.2011.00777.X

Meister M, Kahl P, Muley T, Morresi-Hauf A, Sebening C, Kern MA, Breinig M, Schnabel P, Dienemann H, Schirmacher P, Rieker RJ (2009) Expression and mutational status of PDGFR in thymic tumours. Anticancer Res 29(10):4057–4061

Ströbel P, Bargou R, Wolff A, Spitzer D, Manegold C, Dimitrakopoulou-Strauss A, Strauss L, Sauer C, Mayer F, Hohenberger P, Marx A (2010) Sunitinib in metastatic thymic carcinomas: laboratory findings and initial clinical experience. Br J Cancer 103(2):196–200. doi:10.1038/Sj.Bjc.6605740

Pagano M, Sierra NM, Panebianco M, Rossi G, Gnoni R, Bisagni G, Boni C (2014) Sorafenib efficacy in thymic carcinomas seems not to require c-KIT or PDGFR-alpha mutations. Anticancer Res 34(9):5105–5110

Witkiewicz AK, Knudsen KE, Dicker AP, Knudsen ES (2011) The meaning of p16(Ink4a) expression in tumors: functional significance, clinical associations and future developments. Cell Cycle 10(15):2497–2503

Zou W, Wolchok JD, Chen L (2016) PD-L1 (B7-H1) and PD-1 pathway blockade for cancer therapy: mechanisms, response biomarkers, and combinations. Sci Transl Med 8(328):328rv324. doi:10.1126/Scitranslmed.Aad7118

Topalian SL, Taube JM, Anders RA, Pardoll DM (2016) Mechanism-driven biomarkers to guide immune checkpoint blockade in cancer therapy. Nat Rev Cancer 16(5):275–287. doi:10.1038/Nrc.2016.36

Chen L, Han X (2015) Anti-PD-1/PD-L1 therapy of human cancer: past, present, and future. J Clin Invest 125(9):3384–3391. doi:10.1172/Jci80011

Padda SK, Riess JW, Schwartz EJ, Tian L, Kohrt HE, Neal JW, West RB, Wakelee HA (2015) Diffuse high intensity PD-L1 staining in thymic epithelial tumors. J Thorac Oncol: Off Publ Int Assoc Study Lung Cancer 10(3):500–508. doi:10.1097/Jto.0000000000000429

Katsuya Y, Fujita Y, Horinouchi H, Ohe Y, Watanabe S, Tsuta K (2015) Immunohistochemical status of PD-L1 in thymoma and thymic carcinoma. Lung Cancer 88(2):154–159. doi:10.1016/J.Lungcan.2015.03.003

Patel SP, Kurzrock R (2015) PD-L1 expression as a predictive biomarker in cancer immunotherapy. Mol Cancer Ther 14(4):847–856. doi:10.1158/1535-7163.Mct-14-0983

Carracedo A, Alimonti A, Pandolfi PP (2011) PTEN level in tumor suppression: how much is too little? Cancer Res 71(3):629–633. doi:10.1158/0008-5472.Can-10-2488

Roh MR, Gupta S, Park KH, Chung KY, Lauss M, Flaherty KT, Jönsson G, Rha SY, Tsao H (2016) Promoter methylation of PTEN is a significant prognostic factor in melanoma survival. J Invest Dermatol 136(5):1002–1011. doi:10.1016/J.Jid.2016.01.024

Ye M, Zhang X, Li N, Zhang Y, Jing P, Chang N, Wu J, Ren X, Zhang J (2016) ALK and ROS1 as targeted therapy paradigms and clinical implications to overcome crizotinib resistance. Oncotarget 7(11):12289–12304. doi:10.18632/Oncotarget.6935

Acknowledgments

Open access funding provided by Medical University of Vienna. We are very grateful to Prof. Alexander Marx, Medical University Mannheim/Heidelberg, for reviewing the histology of several cases included in this study. Furthermore, we are thankful to Dr. Ulrike Setinek, Otto Wagner Spital Vienna, for supplying two thymoma specimens.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Supplementary Fig. S1

Overall survival of patients with thymic carcinomas with a normal or mutated (= mutated and/or deleted) CDKN2A gene (PDF 119 kb)

Supplementary Fig. S2

Overall survival of patients with thymic carcinomas with a normal or mutated (= mutated and/or deleted) TP53 gene (PDF 123 kb)

Supplementary Fig. S3

PDGFRA immunohistochemistry with low expression in a type A thymoma (a) and high expression in a thymic carcinoma (b). Original magnification x400(PDF 2457 kb)

Supplementary Fig. S4

PD-L1 immunohistochemistry with absent expression in a type A thymoma (a) and expression in a thymic carcinoma (b). Original magnification x400(PDF 1990 kb)

Supplementary Fig. S5

Overall survival of patients with thymic carcinomas negative or positive for PD-L1 protein expession (PDF 122 kb)

Supplementary Fig. S6

Overall survival of patients with thymic carcinomas negative or positive for p16INK4A protein expession (PDF 88 kb)

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Enkner, F., Pichlhöfer, B., Zaharie, A.T. et al. Molecular Profiling of Thymoma and Thymic Carcinoma: Genetic Differences and Potential Novel Therapeutic Targets. Pathol. Oncol. Res. 23, 551–564 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12253-016-0144-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12253-016-0144-8