Abstract

The research investigated the prevalence of nonsuicidal self-injury (NSSI) during the COVID-19 outbreak and identified the psychosocial risk factors among junior high school students in Taiwan. Cross-sectional design was applied and 1,060 participants (Mage = 14.66, SD = 0.86 years) were recruited into the study. The prevalence of NSSI was found to be 40.9% (95% confidence interval, 37.9%-43.9%) during the COVID-19 outbreak. The results suggested that the self-injurers group were mostly female, and scored significantly higher in neuroticism, depression, impulsivity, alexithymia, virtual social support, dissatisfaction with academic performance, and lower in subjective wellbeing, self-esteem, actual social support, and family function than the non-injurers group. In addition, high neuroticism, low self-esteem, high virtual social support, high impulsivity, and high alexithymia were independently predictive in the logistic regression analysis. The principal results of this study suggested that NSSI was extremely prevalent among adolescents during the COVID-19 outbreak, and in particularly, personality and virtual environment risk factors and enhancing self-esteem should be the focus of NSSI preventive strategies when targeting this age population. Our results provide a reference towards designing NSSI prevention programs geared toward the high school population during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The outbreak of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) has a considerable effect on human life including psychological impacts (Asmundson & Taylor, 2020) and mental health problems such as post-traumatic stress, anxiety, depressive symptoms, insomnia, denial, anger, fear as well as grief-related symptoms (Torales et al., 2020; Guessoum et al., 2020; Rajkumar, 2020; Duan et al., 2020). The pandemic has also worsened existing mental health problems (Golberstein et al., 2020), and brought many challenges to the health care system (Bouali et al., 2020; Ilesanmi & Afolabi, 2020). After the world economic crisis in 2008, the impact of recession had a great effect on self-harming behaviors (Hawton et al., 2016). Consequently, it can be assumed that there may also be an upsurge of self-injurious behavior in youth as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic (Fegert et al., 2020). Many researches target the prevention of the disease from the transmission end (Hanscom et al., 2020; Tipaldi et al., 2020). However, to our knowledge, there is no research investigating the effect on nonsuicidal self-injury (NSSI) during COVID-19 outbreak. NSSI has become a major public health concern among adolescents. Defined as the deliberate destruction of body tissue without intent to die, NSSI is often viewed with social disproval and distinguished from behavior whose harmful consequences are unintended (Nock & Favazza, 2009). NSSI has become a growing health problem worldwide. The lifetime prevalence of NSSI was as high as 17.2% among adolescents and 13.4% among young adults (Swannell et al., 2014). Similar prevalence were found across countries ((Giletta et al., 2012; Plener et al., 2009). Moreover, NSSI is a common problem among adolescents and a prominent risk factor for later suicidality (Asarnow et al., 2011; Guan et al., 2012). The DSM-5 emphasized the behavior by including NSSI disorder as a “condition requiring further study” (American Psychiatric Association, 2013). Therefore, it is important to examine the prevalence and psychosocial risk factors associated with the development and maintenance of NSSI, in order to take necessary preventive actions during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Numerous empirical studies have investigated the associations between NSSI and psychosocial risk factors in adolescents (Baetens et al., 2014; Fox et al., 2015; Hankin & Abela, 2011; Martin et al., 2016; Tuisku et al., 2014). A number of models pertaining to NSSI have been proposed, including Nock’s (2009) integrated theoretical model. According to the integrated theoretical model, NSSI is maintained by intrapersonal or interpersonal vulnerability factors through reinforcement processes to regulate affective experiences and social situations (Nock, 2009). This study incorporated the integrated theoretical model as a conceptual framework for understanding psychosocial risk factors for NSSI in adolescents during the COVID-19 outbreak. Intrapersonal and interpersonal vulnerability factors were included to examine NSSI risk factors. In this study, intrapersonal factors included neuroticism, self-esteem, alexithymia, impulsivity, depression, and subjective well-being. Interpersonal factors included family function, actual social support, virtual social support, and dissatisfaction with academic performance. Previous studies have also pointed out that higher levels of neuroticism (Allroggen et al., 2014; Brown, 2009; Kiekens et al., 2015; Mullins-Sweatt et al., 2013), greater impulsivity (Claes & Muehlenkamp, 2013; Hamza et al., 2015), higher levels of depression (Hankin & Abela, 2011; Klonsky et al., 2003; Muehlenkamp & Gutierrez, 2007; Ross & Heath, 2002), greater alexithymia (Cerutti et al., 2018; Garisch & Wilson, 2015; Gatta et al., 2016; Howe-Martin et al., 2012; Lambert and De Man, 2007; Laukkanen et al., 2013; Lüdtke et al., 2016), lower levels of self-esteem (Cawood & Huprich, 2011; Garisch & Wilson, 2015), and lower levels of subjective well-being (Vansteenkiste & Ryan, 2013) were associated with NSSI. In addition, past research also revealed intrapersonal factors, including lower levels of actual social support (Andrews et al., 2014), lower levels of family function (Baetens et al., 2014), and dissatisfaction with academic performance (Mortier et al., 2015) were all correlated with NSSI. Furthermore, no research has investigated the association of virtual social support and NSSI. Concerning the quarantine periods during the COVID-19 outbreak, social-distancing may have an important effect on the mental health of adolescents. Adolescents may be more likely to connect and gain support through the internet. Therefore, we want to examine the association between virtual social support and NSSI during the COVID-19 outbreak.

Past studies found that various psychosocial risk factors are related to NSSI. Nevertheless, few studies have encompassed an inclusive examination that integrated psychological and sociological risk factors aimed at a large sample of junior high school students. Moreover, most research were relatively finite for the sake of investigating a small number of psychosocial risk factors, which limits the comprehensiveness in understanding the association between NSSI and related variables. Owing to limited resources and time during the COVID-19 pandemic, educational agencies, mental health organizations, and educational practices may only focus on a maximum of three to four psychosocial risk factors per time in preventive education. This limits the understanding of NSSI. It is essential to incorporate relevant and multiple critical psychosocial risk factors relating to NSSI. Most importantly, as far as we know, this was the first study to examine the prevalence of NSSI and its psychosocial risk factors in a large sample of adolescents during the COVID-19 outbreak. This study aimed to probe at the prevalence of NSSI and its associations with psychological and sociological risk factors in a large sample of adolescents in Taiwan, and the results will be discussed. Through this investigation, we can provide information to educational agencies and mental health organizations geared towards NSSI prevention policies during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Methods

Participants and Procedure

Cross-sectional design was used to construct this study. The data in junior high school students were recruited during March 2 through March 27, 2020. COVID-19 new cases rapidly increased in February, 2020, forcing schools in Taiwan to extend an additional two-week winter break. Junior high schools opened on February 25th. This study recruited 1244 junior high school students in three schools located in northern Taiwan by stratified and cluster sampling methods. 1060 valid surveys were completed (Mage = 14.66, SD = 0.86 years) in total. Invalid questionnaires and those who did not took part in the administration of the surveys were excluded from the data analysis. The response rate is 85.21%.

The present study protocol was reviewed and approved by the institutional review board at the National Taiwan Normal University. Before assessment implementation, completed informed consent forms were obtained from the teachers of the administered classes, the guidance counselor, and the school principals/guidance director. The research team also provided a pre-training session regarding the procedure of the administration to the guidance counselors. Survey administration was conducted in groups during class time. In attempt to fain truthful responses, students were fully informed of the goal, procedure, research ethics and confidentiality. Written informed consent was also obtained from the participants and their guardians. Data analysis was conducted on the participants who provided two sets of informed consent. At the completion of the surveys, participants were informed that individual results and response feedbacks will be given at the end of the semester. The research methodology is presented in Fig. 1.

Measures

The Socio-Demographic Measures

Gender (female = 1 and male = 2), age, and dissatisfaction with academic performance were assessed.

NSSI (You et al., 2012)

Twelve NSSI behaviors were examined in this study. Participants were asked, “In the past year, have you ever engaged in the following behaviors to deliberately injure yourself but without suicidal intent?” All of the twelve NSSI behavior items were rated on a 6-point scale, ranging from 0 “never” to 5 “five times or more”. A dichotomous variable of NSSI status was computed based on the twelve items. A code of “0” was entered when participants endorsed “never” on all items, and “1” when participants reported having engaged in one or more NSSI acts. The internal consistency coefficient in the current study was .86.

Shortened Chinese Version of Five-Factor Inventory_ Neuroticism Subscale (Chen & Piedmont, 1999; Chien et al., 2007)

We assessed neuroticism personality traits by the neuroticism subscale of Shortened Chinese version of Five-Factor Inventory (Chen & Piedmont, 1999; Chien et al., 2007). This inventory has 31 items, selected from the NEO Five-Factor Inventory (Chen & Piedmont, 1999), and showed good reliability and validity among Chinese adolescents (Chien et al., 2007). The neuroticism subscale contains 6 items and the Cronbach’s alpha coefficient was .81 in this study.

The Short-Form of the Impulsivity Scale (Fu et al., 2007; Li et al., 2002)

The impulsivity scale was an adaptation from the Barratt Impulsivity Scale, which included 15-items. The confirmatory factor analysis displayed two subscales: motor impulsiveness and non-planning (Li et al., 2002). Fu et al. (2007) assessed the construct validity of this scale using confirmatory factor analysis and showed a satisfactory construct validity among adolescents. The scale was rated on a 4-point Likert scale, and the Cronbach’s alpha coefficient was .79 in this study.

Depression Anxiety Stress Scale _ Depression Subscale

The current study incorporated the depression subscale of the Chinese version of the Depression Anxiety Stress Scale (DASS; Taouk et al., 2001). The subscale has seven items, and responses were made on a 4-point Likert scale. The DASS displayed satisfactory factor structure and internal consistency (Taouk et al., 2001). In the present study, the depression subscale showed good internal consistency (α = .85).

The Toronto Alexithymia Scale-20 (TAS-20; Bagby et al., 1994; Parker et al., 2003)

We used the TAS-20 to assess the alexithymia (Bagby et al., 1994). TAS-20 is a self-report scale comprising 20 items on a 5-point scale. Good internal consistency, test-retest reliability (Bagby et al., 1994), and factorial validity (Parker et al., 2003) was found in this scale. In this study, the TAS-20 had a Cronbach’s α value of .80.

The Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale (RSES; Rosenberg, 1965)

The RSES was used in the current study to evaluate global self-esteem. This scale contains 10 items, which yields a single overall score for self-esteem and has good reliability and constructs validity (Rosenberg, 1965). The RSES has also been successfully used among adolescents in Taiwan (Chang et al., 2013), and the internal consistency coefficient for this scale was .89.

Chinese Happiness Inventory (CHI; Lu, 2006)

This study used CHI to assess subjective well-being (Lu, 2006), which is a ten item self-report rated on a 4-point scale. Higher scores represented higher levels of happiness. CHI has displayed good reliability and validity among Chinese adolescents (Lu, 2006). The Cronbach’s alpha coefficient was .90 in the current study.

Social Support Scale (Yeh et al., 2008)

This scale contains 16 items that evaluates perceived social support from friends and parents (Yeh et al., 2008). Higher scores represented a greater degree of perceived actual social support. Lin, Wu, You, Chang, Hu, & Xu (2018) revealed good reliability and validity of this scale among adolescents in Taiwan, and the internal consistency coefficient was .90 in the present study.

Virtual Social Support Scale (VSSS; Yeh et al., 2008)

This scale (Yeh et al., 2008) was revised from the Social Support Scale, and assesses perceived social support from those who are acquainted only through the Internet as distinguished from those known in real life. Moreover, Yeh et al. (2008) added two questions to this scale in accordance with the online environment, and the final VSSS has 10 items. Higher scores represented a greater degree of perceived virtual social support. The scale was rated on a 4-point Likert scale, and the Cronbach’s alpha coefficient was .95 in this study.

Brief Family Function Questionnaire (Chang et al., 2017; Ren et al., 2018)

We used the Brief Family Function Questionnaire to assess family function (Ren et al., 2018), which is a 22 item self-report questionnaire rated on a 5-point Likert scale. This questionnaire includes eight aspects of family functioning, labeled as family cohesion, problem solving, role responsibility, independence, communication, affective responsiveness, family conflict, and emotional involvement. This questionnaire has showed good reliability and validity among adolescents in Taiwan (Chang et al., 2017). The family conflict and emotional involvement subscales were reversed scored, and higher scores indicated healthier family functioning. The internal consistency coefficient for the total scale was .92 in the current study.

Statistical Analysis

SPSS version 18.0 for Windows was used to analyze the data, and the significance level was set at .05. The prevalence for NSSI was calculated. The association between NSSI in the groups and psychosocial risk factors were examined by t-test and χ2 test. Significant factors were further selected and included in the forward logistic regression analysis to examine their associations with NSSI among adolescents.

Results

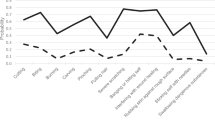

The outbreak of COVID-19 has worsened existing mental health problems, and NSSI is a common problem among adolescents. This study examined the prevalence of NSSI during the COVID-19 outbreak and discovered that the prevalence of NSSI among sample of 1060 adolescents was 40.9% (95% confidence interval, 37.9%–43.9%), and girls reported significantly higher rates of NSSI than did boys. Among self-injurers, 34.2% (n = 145) reported using only one method, and 65.8% (n = 279) reported using multiple methods. Additionally, 18.1% (n = 78) of self-injurers engaged in NSSI only once, and the remaining 81.9% (n = 354) performed NSSI twice or more. Among participants who engage in NSSI, self-cutting was the most prevalent method (21.6%, n = 229), followed by skin scratching (18.0%, n = 190), hair pulling (16.4%, n = 173), biting (14.0%, n = 148), banging the head or other parts of the body against the wall (12.4%, n = 131), carving words or symbols using sharp objects on the skin that leads to bleeding (11.7%, n = 124), punching (9.9%, n = 105), inserting objects to the nail or skin (8.1%, n = 86), erasing skin (7.2%, n = 76), burning (4.1%, n = 43), and dripping acid onto skin (1.2%, n = 13). Scrubbing skin using bleach or cleaner (1.0%, n = 11) was the least prevalent method of NSSI during the COVID-19 pandemic.

In order to take necessary preventive actions to NSSI during the COVID-19 pandemic, this study also examined the association between NSSI and psychosocial risk factors by t-test and χ2 test. Significant factors were further selected and included in the forward logistic regression analysis to explore multiple critical psychosocial risk factors among adolescents. The results in Table 1 showed that all demographic, psychological, and sociological characteristics were significantly different between the self-injurers and non-injurers groups. Participants in the self-injurers group reported higher levels of neuroticism, impulsivity, depression, alexithymia, virtual social support, and dissatisfaction with academic performance, and lower levels of subjective well-being, family function, actual social support, and self-esteem.

Table 2 showed that high neuroticism, high impulsivity, high alexithymia, low self-esteem, and high virtual social support were associated with NSSI in the forward logistic regression analysis. However, gender, depression, subjective well-being, actual social support, family function, and dissatisfaction with academic performance were not related to NSSI in the forward logistic regression analysis. We put each factor into the logistic regression analysis separately, and the result showed that depression (Wald. coeff. = 109.208, p < .001), subjective well-being (Wald. coeff. = 86.722, p < .001), family function (Wald. coeff. = 44.246, p < .001), dissatisfaction with academic performance (Wald. coeff. = 12.794, p < .001), actual social support (Wald. coeff. = 11.477, p < .01), and being female (Wald. coeff. = 10.963, p < .01) were capable of predicting NSSI independently and significantly, but was not able to significantly predict NSSI when other psychosocial risk factors were put into the forward logistic regression analyses. In brief, neuroticism was the first variable to enter the regression model, followed by self-esteem and virtual social support.

Discussion

This study aims to uncover and examine the prevalence of NSSI and related psychosocial risk factors among junior high school students in Taiwan during the COVID-19 outbreak. Overall, the results indicated a 40.9% NSSI prevalence among the participants. The prevalence in our study was increasingly higher than those found in previous researches regarding adolescent samples. For example, Barrocas et al. (2012) indicated 12.7% of ninth-graders engaged in NSSI. You et al. (2011) examined 6374 secondary school students and found a prevalence of 15%; Muehlenkamp et al. (2012) conducted a systematic review of 52 empirical studies and found an average lifetime estimate of 18% for NSSI. Giletta et al. (2012) found 24% of 1862 cross-country adolescents; Claes et al. (2014) assessed 532 high school students and indicated 26.5% of adolescents engaged in NSSI. Zetterqvist et al. (2013) found 35.6% among 3060 Swedish adolescents aged 15–17 years old conducted NSSI. In Taiwan, COVID-19 cases rapidly exploded from February 2020, which resulted in a two-week postponement of the second school semester. Schools started on February 25th and data was gathered during March 2 through March 27, 2020. The extended winter vacation may bring about several psychological stress due to the COVID-19 outbreak. Anxiety, lack of peer contact, and reduced opportunities for stress regulation may be the main concern/affect during COVID-19 among adolescents. Additional challenges may arise to adolescents with trauma experiences and for those who have existing mental health problems (Fegert et al., 2020). COVID-19 brings various aspects of change and stress to adolescents and their families. In order to cope with stress associated with COVID-19, junior high school students may engage in NSSI to regulate negative emotions. The COVID-19 pandemic is still ongoing and affects multiple aspects of daily life. With regard to a high prevalence of NSSI, it is necessary for educational agencies and mental health organization to develop intervention strategies.

Among intrapersonal risk factors, this study found that neuroticism was positively associated with NSSI. This finding corresponds with the findings of previous researches (Allroggen et al., 2014; Brown, 2009; Kiekens et al., 2015; Mullins-Sweatt et al., 2013). Furthermore, this study also found that neuroticism had the greatest influence on NSSI among other intrapersonal and interpersonal categories in the logistic regression model. Neuroticism individuals have the tendency to experience negative emotions, such as anxiety, anger, and depressed mood (Brown, 2009). They may perceive more stress, interpret situations as more threatening and view minor frustrations as more hopelessly difficult (Hettema et al., 2006; Penley & Tomaka, 2002). NSSI is likely to be engaged as a way to cope or tolerate negative feelings. Individuals with high neuroticism tend to be more sensitive to COVID-19-related stress and interpret the situation as more difficult to deal with, increasing the chance of NSSI to regulate negative feelings, which increases the risk of NSSI.

This study showed NSSI was negatively associated with self-esteem, which is consistent with past studies (Cawood & Huprich, 2011; Lundh et al., 2007; Tatnell et al., 2014). NSSI may also serve the function of self- punishment (Klonsky, 2007; Nock, 2009). Self-criticism, conceptually similar to low self-esteem, is consistently associated to NSSI (Glassman et al., 2007; Swannell et al. 2012). Compared to indirect forms of self-injury, NSSI individuals showed more self-criticism (Germain & Hooley, 2012). On the contrary, people who are high on self-esteem may be less likely to conduct NSSI. Self-esteem is defined as one’s general sense of his or her value or worth (Rosenberg, 1979), and may be hypothesized to act as a mediator in the relationship between several factors and NSSI (Cawood & Huprich, 2011). Past empirical studies have shown that social support significantly predicted one’s level of self-esteem (Hoffman et al., 1988; Kong & You, 2013). However, the decrease of interaction and social support during the COVID-19 quarantine may affect adolescents’ self-esteem.

NSSI is positively related to impulsivity and alexithymia, which corresponds with the results of past studies (Claes & Muehlenkamp, 2013; Crowell et al., 2012; Cawood & Huprich, 2011; Norman & Borrill, 2015). Individuals with high impulsive may act rashly when experiencing negative emotions in order to gain immediate relief from distress without considering negative consequences of their behavior (lack of premeditation) and tend to quit when faced with frustration or boredom (lack of perseverance) (Glenn & Klonsky, 2010; Lynam et al., 2011; Mullins-Sweatt et al., 2013). NSSI serves as an effective way to regulate aversive emotions (Klonsky & Glenn, 2009, Nock & Prinstein, 2004), therefore, impulsive individuals may be at risk for NSSI (Hamza et al., 2015). On the other hand, adolescents who are high on alexithymia tend to have difficulties regulating and expressing their emotion. Adolescents with high impulsivity may be more likely to engage in NSSI during the COVID-19 outbreak, especially when exposed to negative feelings, experience stress and lack of opportunities for stress regulation, in order to gain immediate relief without considering the consequences. Likewise, adolescents with high alexithymia may engage in NSSI in order to regulate their feelings.

Among interpersonal risk factors, virtual social support is the only risk factor that was able to predict NSSI in the logistic regression model, which contradicts previous research (Lin et al., 2017). With the global use of the Internet, there is an increasing use of online services to get in touch with peers. Social relations were disrupted during the COVID-19 outbreak. Social distancing triggered isolation and aggravated mental problems. The Internet might ease social interaction (Guessoum et al., 2020; Zalite & Zvirbule, 2020), and online social connections is important for mental health outcomes during the COVID-19 quarantine (Pancani et al., 2020) However, excessive media consumption during times of crisis may be a concern for depression, elevated stress, anxiety and psychological distress (Garfin et al., 2020; Keles et al., 2020). Ellis et al. (2020) found that adolescents’ stress during COVID-19 was related to more loneliness and more depression, especially for adolescents who spend more time on social media. Therefore, virtual social support may be related to excessive use of the internet, which aggravates mental problems and trigger NSSI.

The present study found that depression and dissatisfaction with academic performance were significantly higher, actual social support, subjective well-being and family function were significantly lower in the NSSI group compared to the non-NSSI group, which corresponded with prior studies on NSSI (Barrocas et al., 2015; Kiekens et al., 2016; Vansteenkiste & Ryan, 2013; Andrews et al., 2014; Baetens et al., 2014). However, in the forward logistic regression analyses, these factors were unable to significantly predict NSSI when entered after other risk factors. Moreover, this study also added each factor separately into the logistic regression analysis, and found that depression (Wald. coeff. = 109.208, p < .001), subjective well-being (Wald. coeff. = 86.722, p < .001), family function (Wald. coeff. = 44.246, p < .001), dissatisfaction with academic performance (Wald. coeff. = 12.794, p < .001), actual social support (Wald. coeff. = 11.477, p < .01), and being female (Wald. coeff. = 10.963, p < .01) were all able to independently and significantly predict NSSI, but was unable to significantly predict NSSI when other psychosocial risk factors were added into the logistic regression analyses. It is probable that the relationship is mediated by other psychosocial risk factors. Possible mediating factors need to be examined in future studies. Comprehensively, the main feature of this study falls on the incorporation of multiple psychosocial risk factors associated with NSSI during the COVID-19 outbreak.

Despite the significance of our findings, the following limitations should be noted. First, recruiting only junior high school students may limit the generalizability of results, and findings may not be applicable to all NSSI students of similar age who did not attend school due to the pandemic. Second, no causal relationships could be determined due to the cross-sectional nature of the study design. Furthermore, all information was acquired from self-report questionnaires. The reliability of the results depended heavily on the honesty of participants and that they have a clear understanding of the meaning of questions. Response bias may exist. Future work using multiple-method assessments may provide a richer and more thorough understanding of NSSI.

Conclusion

The COVID-19 pandemic influenced people’s lives to a great extent, leading to psychological reactions and mental health problems. NSSI appears to be an important problem for adolescents. As far as we know, this was the first study to investigate the prevalence of NSSI and examined the associations between NSSI and several psychosocial risk factors among junior high school students during the COVID-19 outbreak. This study found that the prevalence of NSSI among junior high school students in Taiwan was extremely high during the COVID-19 outbreak. Furthermore, this study also indicated that a majority of students in the self-injurers group was female, and showed significantly higher scores in neuroticism, impulsivity, depression, alexithymia, virtual social support, dissatisfaction with academic performance, and lower scores in self-esteem, subjective well-being, actual social support, and family function than the non-injurers group. More importantly, high neuroticism, high impulsivity, high alexithymia, high virtual social support and low self-esteem were all independently predictive in the forward logistic regression analysis. Neuroticism was the first variable to be entered into the regression model, followed by self-esteem and virtual social support. The limitations of this study were the recruitment of solely junior high school students and having a cross-sectional research design. However, the results can serve as a guideline for mental health organizations and educational agencies to create policies and designs suitable to NSSI prevention programs geared toward the junior high school population during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Data Availability

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Allroggen, M., Kleinrahm, R., Rau, T. A. D., Weninger, L., Ludolph, A. G., & Plener, P. L. (2014). Nonsuicidal self-injury and its relation to personality traits in medical students. The Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease., 202(4), 300–304. https://doi.org/10.1097/NMD.0000000000000122.

American Psychiatric Association. (2013). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (5th ed.). Author.

Andrews, T., Martin, G., Hasking, P., & Page, A. (2014). Predictors of onset for non-suicidal self-injury within school-based sample of adolescent. Prevention Science, 15, 850–859. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11121-013-0412-8.

Asarnow, J. R., Porta, G., Spirito, A., Emslie, G., Clarke, G., Wagner, K. D., Vitiello, B., Keller, M., Birmaher, B., McCracken, J., Mayes, T., Berk, M., & Brent, D. A. (2011). Suicide attempts and nonsuicidal self-injury in the treatment of resistant depression in adolescents: Findings from the TORDIA study. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 50(8), 772–781. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaac.2011.04.003.

Asmundson, G. J. G., & Taylor, S. (2020). Coronaphobia: Fear and the 2019-nCoV outbreak. Journal of Anxiety Disorders, 70, 102196. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.janxdis.2020.102196.

Baetens, I., Claes, L., Onghena, P., Grietens, H., Van Leeuwen, K., Peters, C., Wiersema, J. R., & Griffith, J. W. (2014). Non-suicidal self-injury in adolescence: A longitudinal study of the relationship between NSSI, psychological distress and perceived parenting. Journal of Adolescence, 37(6), 817–826. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.adolescence.2014.05.010.

Bagby, R. M., Parker, J. D. A., & Taylor, G. J. (1994). The twenty-item Toronto alexithymia scale: I. Item selection and cross-validation of the factor structure. Journal of Psychosomatic Research, 38, 23–32. https://doi.org/10.1016/0022-3999(94)90005-1.

Barrocas, A. L., Hankin, B. L., Young, J. F., & Abela, J. R. (2012). Rates of nonsuicidal self-injury in youth: Age, sex, and behavioral methods in a community sample. Pediatrics, 130(1), 39–45. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2011-2094.

Barrocas, A. L., Giletta, M., Hankin, B. L., Prinstein, M. J., & Abela, J. R. Z. (2015). Nonsuicidal self-injury in adolescence: Longitudinal course, trajectories, and intrapersonal predictors. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 43(2), 369–380. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10802-014-9895-4.

Brown, S. A. (2009). Personality and non-suicidal deliberate self-harm: Trait differences among a non-clinical population. Psychiatry Research, 169, 28–32. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2008.06.005.

Bouali, H., Okereke, M., Adebisi, Y. A., & Lucero-Prisno, D. E. I. I. I. (2020). Impact of COVID-19 on pharmacy education., 2, 92–95. https://doi.org/10.28991/SciMedJ-2020-02-SI-8.

Cawood, C. D., & Huprich, S. K. (2011). Late adolescent nonsuicidal self-injury: The roles of coping style, self-esteem, and personality pathology. Journal of Personality Disorders., 25(6), 765–781. https://doi.org/10.1521/pedi.2011.25.6.765.

Cerutti, R., Zuffiano, A., & Spensieri, V. (2018). The role of difficulty in identifying and describing feelings in non-suicidal self-injury behavior (NSSI): Associations with perceived attachment quality, stressful life events, and suicidal ideation. Frontiers in Psychology, 9, 318. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2018.00318.

Chang, F. C., Lee, C. M., Chiu, C. H., Hsi, W. Y., Huang, T. F., & Pan, Y. C. (2013). Relationships among cyberbullying, school bullying, and mental health in Taiwanese adolescents. Journal of School Health, 83, 454–462. https://doi.org/10.1111/josh.12050.

Chang, Y. H., Lin, M. P., Hong, F. Y., Hu, W. H., & Wu, Y. W. (2017). Family function, depressive mood and Internet addiction among senior high school students. Bulletin of Educational Psychology, 48(4), 531–550.

Chen, M. C., & Piedmont, R. L. (1999). Development and validation of the NEO-PI-R for a Taiwanese sample. In T. Sugiman, M. Karasawa, J. H. Liu, & C. Ward (Eds.), Progress in Asian social psychology (Vol. 2, pp. 105–119). Kyoyook-Kwahak-Sa.

Chien, L. L., Ko, H. C., & Wu, J. Y. (2007). The five-factor model of personality and depressive symptoms: One-year follow-up. Personality and Individual Differences, 43, 1013–1023. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2007.02.022.

Claes, L., Luyckx, K., & Bijttebier, P. (2014). Non-suicidal self-injury in adolescents: Prevalence and associations with identity formation above and beyond depression. Personality and Individual Differences, 61–62, 101–104. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2013.12.019.

Claes, L., & Muehlenkamp, J. (2013). The relationship between the UPPS-P impulsivity dimensions and nonsuicidal self-injury characteristics in male and female high-school students. Psychiatry Journal, 2013, 1–5. https://doi.org/10.1155/2013/654847.

Crowell, S. E., Beauchaine, T. P., Hsiao, R. C., Vasilev, C. A., Yaptangco, M., Linehan, M. M., & McCauley, E. (2012). Differentiating adolescent self-injury from adolescent depression: Possible implications for borderline personality development. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 40, 45–57. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10802-011-9578-3.

Duan, L., Shao, X., Wang, Y., Huang, Y., Miao, J., Yang, X., & Zhu, G. (2020). An investigation of mental health status of children and adolescents in China during the outbreak of COVID-19. Journal of Affective Disorders, 275, 112–118. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2020.06.029.

Ellis, W. E., Dumas, T. M., & Forbes, L. M. (2020). Physically isolated but socially connected: Psychological adjustment and stress among adolescents during the initial COVID-19 crisis. Canadian Journal of Behavioural Science / Revue canadienne des sciences du comportement, 52(3), 177–187. https://doi.org/10.1037/cbs0000215.

Fegert, J. M., Vitiello, B., Plener, P. L., & Clemens, V. (2020). Challenges and burden of the coronavirus 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic for child and adolescent mental health: A narrative review to highlight clinical and research needs in the acute phase and the long return to normality. Child and Adolescent Psychiatry and Mental Health, 14, 20. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13034-020-00329-3.

Fox, K. R., Franklin, J. C., Ribeiro, J. D., Kleiman, E. M., Bentley, K. H., & Nock, M. K. (2015). Meta-analysis of risk factors for nonsuicidal self-injury. Clinical Psychology Review, 42, 156–167. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2015.09.002.

Fu, A. T., Ko, H. C., Wu, J. Y., Cherng, B. L., & Cheng, C. P. (2007). Impulsivity and expectancy in risk for alcohol use: Comparing male and female college students in Taiwan. Addictive Behaviors, 32, 1887–1896. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.addbeh.2007.01.003.

Garfin, D. R., Silver, R. C., & Holman, E. A. (2020). The novel coronavirus (COVID-2019) outbreak: Amplification of public health consequences by media exposure. Health Psychology, 39(5), 355–357. https://doi.org/10.1037/hea0000875.

Garisch, J. A., & Wilson, M. S. (2015). Prevalence, correlates, and prospective predictors of non-suicidal self-injury among New Zealand adolescents: Cross-sectional and longitudinal survey data. Child and Adolescent Psychiatry Mental Health, 9, 28. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13034-015-0055-6.

Gatta, M., Dal Santo, F., Rago, A., Spoto, A., & Battistella, P. A. (2016). Alexithymia, impulsiveness, and psychopathology in nonsuicidal self-injured adolescents. Neuropsychiatric Disease and Treatment, 12, 2307–2317. https://doi.org/10.2147/NDT.S106433.

Germain, S. A., & Hooley, J. M. (2012). Direct and indirect forms of non-suicidal self-injury: Evidence for a distinction. Psychiatry Research, 197(1–2), 78–84. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2011.12.050.

Giletta, M., Scholte, R. H., Engels, R. C., Ciairano, S., & Prinstein, M. J. (2012). Adolescent non-suicidal self-injury: A cross-national study of community samples from Italy, the Netherlands and the United States. Psychiatry Research, 197(1), 66–72. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2012.02.009.

Glassman, L. H., Weierich, M. R., Hooley, J. M., & Deliberto, T.L.& Nock, M.K. (2007). Child maltreatment, non-suicidal self-injury, and the mediating role of self-criticism. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 45(10), 2483–2490. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.brat.2007.04.002.

Glenn, C. R., & Klonsky, E. D. (2010). A multimethod analysis of impulsivity in nonsuicidal self-injury. Personality Disorders: Theory, Research, and Treatment, 1, 67–75. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0017427.

Golberstein, E., Wen, H., & Miller, B. F. (2020). Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) and mental health for children and adolescents. JAMA Pediatrics, 174(9), 819–820. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapediatrics.2020.1456.

Guan, K., Fox, K. R., & Prinstein, M. J. (2012). Nonsuicidal self-injury as a time-invariant predictor of adolescent suicide ideation and attempts in a diverse community sample. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 80(5), 842–849. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0029429.

Guessoum, S. B., Lachal, J., Radjack, R., Carretier, E., Minassian, S., Benoit, L., & Moro, M. R. (2020). Adolescent psychiatric disorders during the COVID-19 pandemic and lockdown. Psychiatry Research, 291, 113264. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2020.113264.

Hamza, C. A., Willoughby, T., & Heffer, T. (2015). Impulsivity and nonsuicidal self-injury: A review and meta-analysis. Clinical Psychology Review, 38, 13–24. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2015.02.010.

Hankin, B. L., & Abela, J. R. Z. (2011). Nonsuicidal self-injury in adolescence: Prospective rates and risk factors in a 2 ½year longitudinal study. Psychiatry Research, 186(1), 65–70. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2010.07.056.

Hanscom, D., Clawson, D. R., Porges, S. W., Bunnage, R., Aria, L., Lederman, S., Taylor, J., & Carter, C. S. (2020). Polyvagal and global cytokine theory of safety and threat Covid-19 - plan B. SciMedicine Journal, 2, 9–27. https://doi.org/10.28991/SciMedJ-2020-02-SI-2.

Hawton, K., Bergen, H., Geulayov, G., Waters, K., Ness, J., Cooper, J., & Kapur, N. (2016). Impact of the recent recession on self-harm: Longitudinal ecological and patient-level investigation from the multicentre study of self-harm in England. Journal of Affective Disorders, 191, 132–138. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2015.11.001.

Hettema, J. M., Neale, M. C., Myers, J. M., Prescott, C. A., & Kendler, K. S. (2006). A population-based twin study of the relationship between neuroticism and internalizing disorders. The American Journal of Psychiatry, 163(5), 857–864. https://doi.org/10.1176/ajp.2006.163.5.857.

Hoffman, M. A., Ushpiz, V., & Levy-Shiff, R. (1988). Social support and self-esteem in adolescence. Journal of Youth and Adolesence, 17(4), 307–316.

Howe-Martin, L. S., Murrell, A. R., & Guarnaccia, C. A. (2012). Repetitive nonsuicidal self-injury as experiential avoidance among a community sample of adolescents. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 68(7), 809–829. https://doi.org/10.1002/jclp.21868.

Ilesanmi, O., & Afolabi, A. (2020). Time to move from vertical to horizontal approach in our COVID-19 response in Nigeria. Scimedicine Journal, 2, 28–29. https://doi.org/10.28991/SciMedJ-2020-02-SI-3.

Keles, B., McCrae, N., & Grealish, A. (2020). A systematic review: The influence of social media on depression, anxiety and psychological distress in adolescents. International Journal of Adolescence and Youth, 25(1), 79–93. https://doi.org/10.1080/02673843.2019.1590851.

Kiekens, G., Bruffaerts, R., Nock, M. K., Van de Ven, M., Witteman, C., Mortier, P., Demyttenaere, K., & Claes, L. (2015). Non-suicidal self-injury among Dutch and Belgian adolescents: Personality, stress and coping. European Psychiatry, 30(6), 743–749. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eurpsy.2015.06.007.

Kiekens, G., Claes, L., Demyttenaere, K., Auerbach, R. P., Green, J. G., Kessler, R. C., Mortier, P., Nock, M. K., & Bruffaerts, R. (2016). Lifetime and 12-month non-suicidal self-injury and academic performance in college freshmen. Suicide & Life-Threatening Behavior, 46(5), 563–576. https://doi.org/10.1111/sltb.12237.

Klonsky, E. D., Oltmanns, T. F., & Turkheimer, E. (2003). Deliberate self-harm in a nonclinical population: Prevalence and psychological correlates. The American Journal of Psychiatry, 160, 1501–1508. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ajp.160.8.1501.

Klonsky, E. D. (2007). The functions of deliberate self-injury: A review of the evidence. Clinical Psychology Review, 27(2), 226–239. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2006.08.002.

Klonsky, E. D., & Glenn, C. R. (2009). Assessing the functions of non-suicidal self-injury: Psychometric properties of the inventory of statements about self-injury (ISAS). Journal of Psychopathology and Behavioral Assessment, 31(3), 215–219. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10862-008-9107-z.

Kong, F., & You, X. (2013). Loneliness and self-esteem as mediators between social support and life satisfaction in late adolescence. Social Indicators Research, 110, 271–279. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-011-9930-6.

Lambert, A., & de Man, A.F. (2007). Alexithymia, depression, and self-mutilation in adolescent girls. North American Journal of Psychology, 9, 555–566

Laukkanen, E., Rissanen, M., Tolmunen, T., Kylmä, J., & Hintikka, J. (2013). Adolescent self-cutting elsewhere than on the arms reveals more serious psychiatric symptoms. European Child & Adolescent Psychiatry., 22(8), 501–510. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00787-013-0390-1.

Li, C. H., Ko, H. C., Weng, L. J., Liau, L. C., & Lu, R. B. (2002). The development of an impulsiveness scale: Psychometric properties and relation to antisocial personality disorder. Chinese Journal of Psychology., 44, 109–119.

Lin, M. P., You, J., Ren, Y., Wu, J. Y. W., Hu, W. H., Yen, C. F., & Zhang, X. (2017). Prevalence of nonsuicidal self-injury and its risk and protective factors among adolescents in Taiwan. Psychiatry Research, 225, 119–127. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2017.05.028.

Lin, M. P., Wu, J. Y. W., You, J., Chang, K. M., Hu, W. H., & Xu, S. (2018). Association between online and offline social support and Internet addiction in a representative sample of senior high school students in Taiwan: the mediating role of self-esteem. Computers in Human Behavior, 84, 1–7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2018.02.007.

Lüdtke, J., In-Albon, T., Michel, C., & Schmid, M. (2016). Predictors for DSM-5 nonsuicidal self-injury in female adolescent inpatients: The role of childhood maltreatment, alexithymia, and dissociation. Psychiatry Research, 239, 346–352. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2016.02.026.

Lundh, L., Karim, J., & Quilish, E. (2007). Deliberate self-harm in 15-year-old adolescents: A pilot study with a modified version of the non-suicidal self-injury inventory. Scandinavian Journal of Psychology, 48, 33–41. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9450.2007.00567.x.

Lynam, D. R., Miller, J. D., Miller, D. J., Bornovalova, M. A., & Lejuez, C. W. (2011). Testing the relations between impulsivity-related traits, suicidality, and nonsuicidal self-injury: A test of the incremental validity of the UPPS model. Personality Disorders, 2, 151–160. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0019978.

Lu, L. (2006). "Cultural fit": individual and societal discrepancies in values, beliefs, and subjective well-being. Journal of Social Psychology, 146(2), 203–221. https://doi.org/10.3200/SOCP.146.2.203-221.

Martin, J., Bureau, J.-F., Yurkowski, K., Fournier, T. R., Lafontaine, M.-F., & Cloutier, P. (2016). Family-based risk factors for non-suicidal self-injury: Considering influence of maltreatment, adverse family life experiences, and parent-child relational risk. Journal of Adolescence, 49, 170–180. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.adolescence.2016.03.015.

Mortier, P., Demyttenaere, K., Auerbach, R. P., Green, J. G., Kessler, R. C., Kiekens, G., Nock, M. K., & Bruffaerts, R. (2015). The impact of lifetime suicidality on academic performance in college freshmen. Journal of Affective Disorders, 186, 254–260. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2015.07.030.

Muehlenkamp, J. J., & Gutierrez, P. M. (2007). Risk for suicide attempts among adolescents who engage in non-suicidal self-injury. Archives of Suicide, 11(1), 69–82. https://doi.org/10.1080/13811110600992902.

Muehlenkamp, J. J., Claes, L., Havertape, L., & Plener, P. L. (2012). International prevalence of adolescent non-suicidal self-injury and deliberate self-harm. Child and Adolescent Psychiatry and Mental Health, 6(10), 1–9. https://doi.org/10.1186/1753-2000-6-10.

Mullins-Sweatt, S. N., Lengel, G. J., & Grant, D. M. (2013). Non-suicidal self-injury: The contribution of general personality functioning. Personality and Mental Health, 7, 56–68. https://doi.org/10.1002/pmh.1211.

Nock, M. K. (2009). Why do people hurt themselves?: New insights into the nature and functions of self-injury. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 18(2), 78–83. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8721.2009.01613.x.

Nock, M. K., & Prinstein, M. J. (2004). A functional approach to the assessment of self-mutilative behavior. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 72(5), 885–890. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-006X.72.5.885.

Nock, M. K., & Favazza, A. R. (2009). Nonsuicidal self-injury: Definition and classification. In M. K. Nock (Ed.), Understanding nonsuicidal self-injury: Origins, assessment, and treatment (pp. 9–18). American Psychological Association.

Norman, H., & Borrill, J. (2015). The relationship between self-harm and alexithymia. Scandinavian Journal of Psychology, 56(4), 405–419. https://doi.org/10.1111/sjop.12217.

Pancani, L., Marinucci, M., Aureli, N., & Riva, P. (2020). Forced social isolation and mental health: A study on 1006 Italians under COVID-19 quarantine. PsyArXiv Preprints. https://doi.org/10.31234/osf.io/uacfj.

Parker, J. D. A., Talor, G. J., & Bagby, R. M. (2003). The 20-item Toronto alexithymia scale III. Reliability and factorial validity in a community population. Journal of Psychosomatic Research, 55, 269–275. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0022-3999(02)00578-0.

Penley, J. A., & Tomaka, J. (2002). Associations among the big five, emotional responses, and coping with acute stress. Personality and Individual Difference, 32, 1215–1228. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0191-8869(01)00087-3.

Plener, P. L., Libal, G., Keller, F., Fegert, J. M., & Muehlenkamp, J. J. (2009). An international comparison of adolescent non-suicidal self-injury (NSSI) and suicide attempts: Germany and the USA. Psychological Medicine, 39(9), 1549–1558. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0033291708005114.

Rajkumar, R. P. (2020). COVID-19 and mental health: A review of the existing literature. Asian Journal of Psychiatry, 52, 102066. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajp.2020.102066.

Ren, Y., Lin, M. P., Liu, Y. H., Zhang, X., Wu, J. Y. W., Hu, W. H., Xu, S., & You, J. (2018). The mediating role of coping strategy in the association between family functioning and nonsuicidal self-injury among Taiwanese adolescents. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 74(7), 1246–1257. https://doi.org/10.1002/jclp.22587.

Rosenberg, M. (1965). Society and the adolescent self-image. Princeton University Press, New Jersey.

Rosenberg, M. (1979). Conceiving the self. Basic Books.

Ross, S., & Heath, N. L. (2002). A study of the frequency of self-mutilation in a community sample of adolescents. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 31, 67–77. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1014089117419.

Swannell, S., Martin, G., Page, A., Hasking, P., Hazell, P., Taylor, A., & Protani, M. (2012). Child maltreatment, subsequent non-suicidal selfinjury and the mediating roles of dissociation, alexithymia and self-blame. Child Abuse & Neglect, 36(7-8), 572–584. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chiabu.2012.05.005.

Swannell, S. V., Martin, G. E., Page, A., Hasking, P., & St John, N. J. (2014). Prevalence of nonsuicidal self-injury in nonclinical samples: Systematic review, meta-analysis and meta-regression. Suicide and Life-threatening Behavior, 44(3), 273–303. https://doi.org/10.1111/sltb.12070.

Tatnell, R., Kelada, L., Hasking, P., & Martin, G. (2014). Longitudinal analysis of adolescent NSSI: The role of intrapersonal and interpersonal factors. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 42, 885–896. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10802-013-9837-6.

Taouk, M., Lovibond, P. F., & Laube, R. (2001). Psychometric properties of a Chinese version of the short depression anxiety stress scales (DASS21). New South Wales Transcultural Mental Health Centre, Cumberland Hospital.

Tipaldi, M. A., Lucertini, E., Orgera, G., Zolovkins, A., Lauirno, F., Ronconi, E., Pisano, A., Salandra, P. C. L., Laghi, A., & Rossi, M. (2020). How to manage the COVID-19 diffusion in the angiography suite: Experiences and results of an Italian interventional radiology unit. SciMedicine Journal, 2, 1–8. https://doi.org/10.28991/SciMedJ-2020-02-SI-1.

Torales, J., Higgins, M. O., Castaldelli-Maia, J. M., & Ventriglio, A. (2020). The outbreak of COVID-19 coronavirus and its impact on global mental health. International Journal of Social Psychiatry, 66(4), 317–320. https://doi.org/10.1177/0020764020915212.

Tuisku, V., Kiviruusu, O., Pelkonen, M., Karlsson, L., Strandholm, T., & Marttunen, M. (2014). Depressed adolescents as young adults—Predictors of suicide attempt and non-suicidal self-injury during an 8-year follow-up. Journal of Affective Disorders, 152, 313–319. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2013.09.031.

Vansteenkiste, M., & Ryan, R. M. (2013). On psychological growth and vulnerability: Basic psychological need satisfaction and need frustration as a unifying principle. Journal of Psychotherapy Integration, 23(3), 263–280. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0032359.

Yeh, Y. C., Ko, H. C., Wu, J. Y. W., & Cheng, C. P. (2008). Gender differences in relationships of actual and virtual social support to internet addiction mediated through depressive symptoms among college students in Taiwan. Cyberpsychology & Behavior, 11, 485–487. https://doi.org/10.1089/cpb.2007.0134.

You, J., Leung, F., & Fu, K. (2012). Exploring the reciprocal relations between nonsuicidal self-injury, negative emotions and relationship problems in Chinese adolescents: A longitudinal cross-lag study. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 40(5), 829–836. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10802-011-9597-0.

You, J., Leung, F., Fu, K., & Lai, C. M. (2011). The prevalence of nonsuicidal self-injury and different subgroups of self-injurers in Chinese adolescents. Archives of Suicide Research, 15(1), 75–86. https://doi.org/10.1080/13811118.2011.540211.

Zalite, G., & Zvirbule, A. (2020). Digital readiness and competitiveness of the EU higher education institutions: The COVID-19 pandemic impact. Emerging Science Journal, 4(4), 297–304. https://doi.org/10.28991/esj-2020-01232.

Zetterqvist, M., Lundh, L. G., Dahlström, Ö., & Svedin, C. G. (2013). Prevalence and function of non-suicidal self-injury (NSSI) in a community sample of adolescents, using suggested DSM-5 criteria for a potential NSSI disorder. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 41, 759–773. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10802-013-9712-5.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Tang, WC., Lin, MP., You, J. et al. Prevalence and psychosocial risk factors of nonsuicidal self-injury among adolescents during the COVID-19 outbreak. Curr Psychol 42, 17270–17279 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-021-01931-0

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-021-01931-0