Abstract

The aim of the research presented in this article was to develop a comprehensive model and measurement of marital goals. The aim of Study 1 was to validate the initial model of marital goals according to Schwartz’s model of values (defined as general transsituational goals). The sample consisted of 684 participants (50% female), all of whom were either married or cohabiting couples aged between 25 and 60 years (M = 37.2; SD = 5.3). The obtained results led to a modification of our initial theoretical model. In the final version of the model, we distinguished eight types of marital goals located in a circular way around two basic dimensions that were similar but not identical to those of Schwartz’s model: (1) oneself versus other focus and (2) relationship commitment versus avoidance. We validated the model in Study 2 in another sample of 1268 participants (50% female) with married couples aged between 18 and 86 years (M = 47.2; SD = 16.1). The measurement model was confirmed through a confirmatory factor analysis; the circular structure was confirmed through multidimensional scaling; the validity of the distinguished goals was confirmed through correlational analyses with value priorities, and marital satisfaction.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

The main aim of the research presented in this paper was to develop a model and measurement of marital goals. Marital goals are considered to be one of the factors explaining marital satisfaction (Brunstein et al. 1996; Fitzsimons and Shah 2008; Light and Fitzsimons 2014); however, there is no comprehensive catalog, model or instrument in the literature to measure such goals. In this paper, we fill this gap by developing (1) a circular model of marital goals that was inspired by Schwartz’s model of basic human values (Schwartz et al. 2012), which are defined as general transsituational goals, and (2) a measurement instrument to measure marital goals.

Generally speaking, a goal can be defined as a subjectively-desired state that an individual is attempting to achieve (Kruglanski 1996; Kruglanski et al. 2002) and is therefore considered important (Moskowitz and Grant 2009). Fulfilling a goal is perceived as a positive event leading to positive affect and failing to fulfill a goal is perceived as a negative event leading to negative affect (Lewis 1990). Goals can be differentiated in terms of their concreteness-abstractness, and their importance constitutes a hierarchy: Some goals are individually considered to be more important than others, which is one of the individual differences between people.

Literature describing marriage in the context of the realization of marital goals is limited. Two theories – the Approach-Avoidance Goals Theory (Gable and Impett 2012) and the Self-Image and Compassionate Goals Theory (Canevello and Crocker 2015) focus only on one selected dimension of relationship goals (approach-avoidance and toward others-toward oneself, respectively). The Dynamic Goal Theory, as proposed by Li and Fung (2011), clarifies and analyzes the relationship between marital goals and marital satisfaction. This model differentiates goals for subsequent phases of a relationship from a life-span perspective. However, it does not propose any instrument to measure these goals, and it does not take individual differences in terms of which goals people find important into account. The aim of our research was to bridge this gap and provide a comprehensive model of marital goals and an instrument to measure these goals.

Dimensions of Marital Goals

One of the basic dimensions of marital goals described in the literature is the approach versus avoidance motivation. The concepts of motivation to approach rewards versus motivation to avoid threats is used in many fields of psychological research (Elliot 1997; Higgins 1998). Approaching social goals steers individuals in the direction of possible positive outcomes like intimacy and relationship growth. On the other hand, avoidance of social goals direct individuals away from conflict and rejection. This approach-avoidance distinction has been adopted in research on romantic relationships, including Approach-Avoidance Goals Theory (Gable and Impett 2012) and Attachment Theory (Mikulincer and Shaver 2007).

Another important dimension of marital goals is goals toward others (benevolent goals) versus goals toward oneself (selfish goals; Canevello and Crocker 2015). Benevolent goals (e.g., compassionate goals) are usually selected by people who are more helpful and responsive to others (Crocker and Canevello 2008; Canevello and Crocker 2010). Individuals who value this type of goals are also more confident when it comes to relationships (Canevello et al. 2013), and think that relationships can be improved (Canevello and Crocker 2011). Selfish goals (e.g., self-image goals) are usually chosen by people who feel upset, disoriented, and isolated when it comes to their social interactions (Canevello and Crocker 2015). Individuals with selfish goals support others and respond to others’ needs less frequently (Crocker and Canevello 2008; Canevello and Crocker 2010), which adversely affects their relationship quality.

A model that directly references the significance of marital goals as well as their relation to marital satisfaction is Li and Fung's (2011) Dynamic Goal Theory. The authors describe three categories of marital goals – companionship goals (based on people’s need for belongingness, intimacy and commitment), personal growth goals (including the development of one’s interests, social contacts, the possibility to construct one’s own identity, accepting challenges or building competences) and instrumental goals (also known as the practical side of marriage, like sharing responsibilities, managing finances or raising children). According to Li and Fung (2011), the priority of marital goals changes across the life span. During early adulthood, personal growth goals have the highest priority, whereas instrumental goals are the least important. In middle adulthood, instrumental goals are the most crucial and in late adulthood companionship goals have the highest priority and personal growth goals the lowest. Li and Fung (2011) state that these tendencies show typical human development - in early adulthood personal growth is the most important, in middle adulthood raising a family is the most important and in late adulthood when people’s time for personal growth is limited and their children are all grown up, partners can only enjoy each other’s company.

This model assigns a different category of marital goals to the subsequent developmental periods of adulthood and does not focus on individual differences in what people may find to be important. Moreover, the three groups of goals (instrumental, companionship, and personal growth goals) are quite general and require detailed conceptualization and operationalization in order to be used in research on marital goals and marital satisfaction.

Our aim is to create a coherent model of marital goals that can be used in further research on marriage and partnership including the motivation to instigate a relationship, the reasons underlying a breakdown in a relationship, relationship satisfaction, and changes occurring from the perspective of life-span psychology (goal priorities may change with age and with relationship duration). Li and Fung (2011) recognized the realization of marital goals as a significant factor influencing marital satisfaction. In general terms, marital satisfaction is influenced by whether the marriage fulfills the needs, expectations, and goals of the spouses in the marriage (Campbell et al. 2001; Dainton 2000; Fletcher et al. 2000; Kelley and Burgoon 1991; Pinsof and Lebow 2005). In our model, we differentiate between the goal priorities set by married couples and the realization of these goals because these may differently influence marital satisfaction. In the final version of the tool proposed in this article, goal priorities and goal realization are measured separately.

Marital Goals as a Contextualization of Transsituational Goals

The optimal catalog of marital goals should be as universal as possible. Hence, we have chosen the catalog of human values from the Schwartz model (1992; Schwartz et al. 2012) as our starting point. We choose this model because Schwartz defines values in terms of transsituational goals, and because the model has empirical support from a large number of studies all over the world indicating its universality (Sagiv et al. 2017).

According to Schwartz (Schwartz 1992; Schwartz et al. 2012), values are defined as desirable and transsituational goals. The structure of the values (goals) forms a circular motivational continuum that can be divided into smaller or larger units, depending on the research aim. In the current version of this theory (Schwartz et al. 2012; Schwartz et al. 2017), the continuum is divided into 19 more narrowly defined values. Values that are placed adjacently to each other on the circle are compatible and can be pursued in the same behavior, whereas values that are located on the opposite sides of the circle are in conflict and cannot be pursued at the same time. The 19 values and broader groups formed by them are indicated in Fig. 1 and the values are defined in Table 1.

Values model by Schwartz et al. (2017) with different possibilities for the division of the circle and basic dimensions

It is also possible to merge more narrowly defined values into larger categories with a similar underlying motivation. One of the most common groupings is four higher-order values located on the opposite sides of two dimensions: conservation versus openness to change and self-transcendence versus self-enhancement. All values can also be described as being located in the matrix produced by two basic dimensions: personal-focus versus social-focus and growth as well as anxiety-free values versus protection and anxiety-avoidance values (see Fig. 1).

Schwartz’s circular model is considered to contain all possible goals valued by people because it identifies the basic relations between value-goals that create the towards-universal matrix for the values (Schwartz et al. 2012; Sagiv et al. 2017). Therefore, we adopted the classification of values-goals by Schwartz as a starting point to identify the marital goals that can be seen as a contextualization of the general, transsituational goals to the context of marriage or relationship.

Study 1: First Version of the Model and Reconceptualization

Materials and Methods

In the first step, we selected values from Schwartz’s model (Schwartz et al. 2012) that could refer to goals in the marital domain. As discussed above, the main claim in Schwartz’s model is the circular continuum of values, which implies a possibility for various segmentations of the circle. There are several possible divisions of the value circle: into 4, 7, 10, 15 and 19 values; each subsequent option is based on distinguishing a larger number of more narrowly and more precisely defined values (Cieciuch and Schwartz 2012; Davidov et al. 2008; Schwartz 1992; Schwartz et al. 2012). While evaluating the possibility of formulating marital goals based on the value goals from Schwartz’s model (Schwartz et al. 2012), we started with the most detailed catalog of values. We acknowledge that such a procedure would lead to a catalog of goals that differ to the well-known four, 10 or 19 values. However, the differentiated goals should be related to each other in accordance with the basic rules of conflict and similarity between value goals. We identified the following values that cannot easily form the basis of marital goals: social security and universalism (which, by definition, concern a broader societal context), humility and face (with both being very narrowly defined values introduced in the latest revision of the model and located on the border between larger groups of values) and power (because of the difficulties in forming partnership goals in terms of power in a socially acceptable manner; however, the self-enhancement values are represented in the selected values even if the power was not included. We come back to this issue in the Discussion). As a result, a catalog of 11 more narrowly defined values emerged for which we formed a definition of partnership goals with three items as indicators for each goal. It is worth noting that in the 11 selected values, all higher order values were represented. The values from Schwartz’s model (Schwartz et al. 2012), our transformation of these values into marital goals, and the items developed to measure these marital goals by the Marital Goals Questionnaire-Pilot Version are presented in Table 1.

Hypothesis

The goal of Study 1 was to validate the model of marital goals based on Schwartz’s model of values (1992; Schwartz et al. 2012). We therefore assumed that:

(1) The measurement of each value-based goal is internally consistent. This hypothesis was tested by Cronbach’s alpha for the scales presented in Table 1. (2) The goals form a circle in a manner similar to the configuration of values in Schwartz’s model (1992; Schwartz et al. 2012). We allowed for the possibility of goals adjacent to each other (e.g., hedonism and stimulation) to be joined, but we expected that the order of the goals would follow the basic rules of compatibility and conflict between goals, and that goals formulated based on opposing values would be located on opposite sides of the circle (e.g., stimulation and safety) according to the circle of values presented in Fig. 1. This hypothesis was tested by using multidimensional scaling (MDS; Cieciuch 2017) on the 11 scales listed in Table 1, and on all items listed in Table 1. MDS is a statistical technique for presenting the similarities or dissimilarities between objects in a graph. The analyzed objects are presented as points in the figure, and the similarities between objects are presented as distances between these points. The more similar the objects are, the closer to each other they appear in the figure. The locations of the points and clusters and the relationships and distances between clusters can be interpreted by the researcher as revealing underlying dimensions that explain the observed similarities and dissimilarities (Cieciuch 2017). We used this analytical approach for the following reasons: Firstly, MDS is a standard analysis of values in Schwartz’s research tradition (Schwartz 1992; Schwartz et al. 2012). Secondly, MDS is especially useful for circular models where other analytical techniques such as exploratory factor analysis are not appropriate because of the expected intercorrelations between variables. Thirdly, MDS enables presenting the structure both at the scale and item levels.

Participants and Procedure

In the study, N = 684 people (50% of them women) participated, from married and cohabiting couples (heterosexual) aged between 25 and 60 years (Mage = 37.2; SDage = 5.3). The study was conducted in Poland and Polish people participated in the study. The participants were recruited by trained students who received course credit for conducting the study. The subjects were given a set of questionnaires, which they submitted to the researchers after completion. Data are available upon request from the authors.

To measure marital goals, we used the Marital Goals-Pilot Version Questionnaire. Participants assessed the extent to which they agreed with each item listed in Table 1 on a 5-point Likert scale (ranging from 1 = I completely disagree to 5 = I completely agree). Each scale consisted of three items. We centered the scales, which is a typical procedure for the analysis of values (Schwartz 1992; Schwartz and Cieciuch 2016) and other circular models (Strus and Cieciuch 2017). Centering the scales is the subtraction of the mean of all items from the score of a given scale.

Results

Hypothesis Validation

The Cronbach’s alphas for the scales were as follows: achievement = .77, benevolence-caring = .61, benevolence-dependability = .73, self-direction–action = .67, self-direction-thought = .76, stimulation = .77, hedonism = .71, tradition = .78, conformity-rules = .71, conformity-interpersonal = .71, and security-personal = .63. These indicators may be deemed sufficient since Cronbach’s alpha depends on the number of items and all the scales consist of three items—which is a relatively low number.

The multidimensional scaling of 11 scales is presented in Fig. 2a (Stress-1 = .16).

The proposed reconceptualization and restructuring of marital goals (Fig. 3a) and Multidimensional scaling of selected items (Fig. 3b) from the Marital Goals-Pilot Version Questionnaire (abbreviations explained in Table 1; the number next to the abbreviations is consistent with the number in the questionnaire and Table 1)

Most scales were located as predicted. The goals related to stimulation (ST), hedonism (HE), and self-direction thought (SDT) were located next to each other, forming an area of openness to change, while conservation, composed of conformity-rules (COR), conformity-interpersonal (COI), and tradition (TR), were located on the opposite side. Between goals of conservation and openness to change, benevolence-caring/benevolence-dependability (BEC/BED) belonging to self-transcendence was positioned on one side and achievement (AC) belonging to self-enhancement on the other. However, two important misplacements can be observed: (1) self-direction action (SDA) was located in the area of self-enhancement on the side of conservation, and (2) security (SE) was located in the area of self-transcendence on the side of openness to change instead of conservation (misplaced values are presented in red loops in Fig. 2a). In sum, SE and SDA swapped places. Had they not done so, it could be assumed that Hypothesis 2 would be confirmed. Since the replacement occurred, two conclusions are possible: First, it could be claimed that Hypothesis 2 was partially confirmed, with an indication of the elements that contradict it. The second possibility would be a revision of theoretical assumptions including an in-depth data analysis. We chose the second option, assuming that the small incongruences between the results and the assumptions may be an empirical suggestion for how to improve the theoretical model.

Previous analyses on the scales demonstrated their internal consistency (satisfactory Cronbach’s alpha), though their structure did not fully meet the theoretical expectations. In light of these inconsistencies, we conducted an analysis at the item level to more closely observe the relationships between marital goals (their structure), which ultimately led us to reconceptualize the model.

Reanalysis of the Results at the Item Level

Since the goals in each item were formulated in positive terms, we centered the items in the same way we centered the scales in the previous analysis - by subtracting the mean of items from each item (Schwartz et al. 2012; Schwartz and Cieciuch 2016). Figure 2b shows the MDS of all items, with the items forming one scale indicated inside the loops.

The results presented in Fig. 2 together with the item content analysis from Table 1 leads to the following conclusions: First, items belonging to one goal-measuring scale cluster next to each other, which further supports the internal consistency of the scales. Simultaneously, however, the proximity between the items of neighboring scales suggests a difficulty in distinguishing between them and, therefore, their convergence. Here, SE and BED are an example. Second, the unexpected positioning of SE was confirmed and even reinforced – the SE items align themselves near the HE items, even though they are positioned opposite each other in Schwartz’s model of values. Safety, as an abstract goal that means avoiding danger and attempting to always be safe, is a value from the conservation group. It seems, however, that in the context of a concrete relationship, it is part of a simply good and satisfying relationship with a partner, which is closely linked to goals formed based on the BED/BEC value and even HE, understood as having a good time with one’s partner. Third, the goals formulated based on the SDA value are so autonomy-reinforcing that they basically imply a lack of an actual relationship with one’s partner. This lack, in turn, is connected to AC, in which marriage is a goal that is necessary to realize personal achievements and is located near the marital goals concerned not with relationships but with rules (COR).

Reconceptualization of the Model

Our starting point was formulating the marital goals based on the most narrowly defined values from Schwartz’s model, grouped into four higher-order values: conservation, openness to change, self-transcendence and self-enhancement. However, the above results suggest that (1) the items for marital goals form slightly different groups than we expected based on Schwartz’s model of values (Schwartz et al. 2012) and (2) the other motivational dimensions differentiated in Schwartz’s (Schwartz et al. 2012) model seem to better organize the item placement than the higher-order values, namely slightly reinterpreted social-focus versus personal-focus, which is similar to the goals toward others versus goals toward oneself proposed by Canevello and Crocker (2015) and protection versus growth, which is similar to avoidance versus approach goals in relationships (Gable and Impett 2012). We label the first dimension oneself versus other focus and the second dimension relationship commitment versus avoidance in order to better capture the relationship content of these dimensions that can be treated as a kind of contextualization of the universal goals from the Schwartz’s model to the content of marriage and relationship.

Applying these two dimensions leads to the formation of four groups of values. Considering the positioning of the items (Fig. 2) and their content (Table 1), we selected items that form groups that are (1) cohesive in terms of content, (2) located next to those with a similar underlying motivation (3) and located opposite to those with a conflicting motivation based on these two distinguished dimensions. In Fig. 3a, we propose selecting the items from the MDS performed on all items and combining the selected items for the new scales. Figure 3b presents the MDS of the selected items only.

Discussion and Summary of the Model Reconceptualization

The obtained results suggested a need to verify our initial theoretical assumptions and led us to formulate eight types of marital goals forming a circle in two dimensions similar but not identical to those from Schwartz’s model (Schwartz et al. 2012). The reconceptualized model is presented in Fig. 4.

Marital goals can therefore be categorized according to two dimensions: a oneself versus other focus, and relationship commitment versus avoidance. The first dimension serves as a basic distinction between the superiority of an individual and his or her needs versus the superiority of the goals and needs of the partner or marriage. It is similar to those described in the literature as goals toward oneself versus goals toward others (for example, as self-image and compassionate goals by Canevello and Crocker 2015).

The second dimension is a basic focus on closeness in the relationship versus closeness avoidance, resulting in the formulation of goals that are based on closeness and enhancing closeness versus formulation of goals in the service of closeness avoidance. This dimension is similar to those described in the Attachment Theory (Mikulincer and Shaver 2007) as well as Approach-Avoidance Goals Theory (Gable and Impett 2012).

These two dimensions make it possible to differentiate four groups of marital goals or, in more detail, eight goals located on the circle formed by these dimensions, as presented in Fig. 4 and described in Table 2.

The model presented in Fig. 4 and the items for measuring the differentiated marital goals were developed based on the analysis of the data obtained. Thus, there is a risk that these are a data-based model and measurement and that they will not be replicable with other data. Therefore, we validated the model in another independent study (Study 2).

Study 2: Model Validation

The goals of Study 2 were as follows: 1) To verify the importance of marital goals model presented in Fig. 4 by using the Marital Goals Questionnaire-Final Version (items from Table 2). We expected to confirm the measurement model in a confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) and the circular structure in MDS, as outlined in Study 1. 2) To verify the model presented in Fig. 4 in terms of the realization of marital goals. To that end, the items were reformulated in accordance with marital goal fulfillment. We expected the confirmation of the measurement model in a CFA and the circular structure in MDS. 3) To verify the external validity of the measured marital goals.

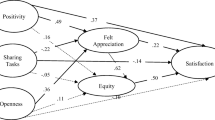

We expected the following for the verification of external validity: (3a) A relationship between goal importance (rather than realization) and the value preferences from Schwartz’s model, such that higher-order values would be most strongly related to their respective marital goals. In particular, we expected that the stable relationship and mutual support goals would be positively correlated with self-transcendence and negatively with self-enhancement values; conversely, the instrumental benefits and personal autonomy protection goals were expected to be positively correlated with self-enhancement and negatively with self-transcendence values; the personal growth and varied lifestyle goals were expected to be positively correlated with openness to change and negatively with conservation values; conversely, the submitting to norms and submitting to the partner goals were expected to be positively correlated with conservation and negatively with openness to change values. (3b) A relationship between goal realization (rather than importance) and marital satisfaction, and in particular, we expected that realizing the goals of relationship commitment (located on the right site on the Fig. 4) would be positively correlated with marital satisfaction and that fulfilling the goals of relationship avoidance (located on the left side on the Fig. 4) would be negatively correlated with marital satisfaction.

Materials and Methods

Participants

There were N = 1266 participants (50% female), who were married (heterosexual) and aged between 18 and 86 years (M = 47.2; SD = 16.1). The study was conducted in Poland. The respondents were recruited by trained students who received course credit for conducting the study. The procedure was the same as in Study 1 and the subjects were given a set of paper questionnaires, which they returned to the researchers after completion. Data are available upon request from the authors.

Method

In this study, the Marital Goals Questionnaire-Final Version was used. The first part concerns the importance of the eight marital goals from Fig. 4, using items from Table 2, and the second part concerns the realization of the goals in the marriage of the respondents. In the first part of the study, the respondents expressed their agreement with each item on a 5-point Likert scale (ranging from 1 = I completely disagree to 5 = I completely agree). In the second part, the respondents assessed their agreement with statements describing the realization of goals in their marriage (items are presented in Table 5). They gave their answers on a 5-point Likert scale (ranging from 1 = definitely no to 5 = definitely yes).

Values were measured by the Portrait Value Questionnaire—Revised (PVQ-RR; Schwartz 2017), developed to measure the 19 values in the refined version of Schwartz’s theory. The questionnaire consists of 57 items describing different people according to what is important to them. Respondents indicated how similar the person described in an item was to themselves, using a 6-point scale (from 1 = not like me at all to 6 = very much like me).

Marital satisfaction was measured using the QMI (Quality Marriage Index) by Norton (1983). The questionnaire consists of 6 items describing global marital satisfaction. Respondents indicate how satisfying their relationship is, using a 7-point scale (from 1 = I definitely do not agree to 7 = I definitely agree).

Results

Table 3 presents the descriptive statistics and Cronbach’s alpha for the scales from both parts of the Marital Goals Questionnaire-Final Version.

The internal stability measured by Cronbach’s alpha is satisfactory - bearing in mind the fact that each scale consists of only three items. The scale distribution is close to normal, apart from the stable relationship and mutual support dimensions, which received somewhat extreme assessments.

Measurement model

The measurement model was tested for eight latent variables for goal importance, each loaded by three items. A separate model was tested for goal realization. We applied the target CFA because of the assumption concerning intercorrelations between scales as a result of the circular structure. Both models (for marital goal importance and marital goals realization) fit the data very well. The goal importance model obtained the following fit indices: CFI = .985, RMSEA = .031 [.026–.036], SRMR = .013 (and for the multigroup CFA across gender subsamples: CFI = .981, RMSEA = .028 [.023–.033], SRMR = .030). The goal realization model obtained the following fit indices: CFI = .981, RMSEA = .038 [.033–.043], SRMR = .012 (and for the multigroup CFA across gender subsamples: CFI = .979, RMSEA = .031 [.027–.036], SRMR = .027).

The item loadings in the goal importance model are presented in Table 4, and the item loadings in the goal realization model are presented in Table 5.

The measurement models fit the data well. The only exception (apart from a few cross loadings) is the unification of the stable relationship and mutual support dimensions. It is not contradictory to the theoretical model because these two scales are expected to be located close to each other as they are two aspects of the marital goals defined in terms of high social focus and high relationship commitment.

Circular structure

The MDS of the importance of the eight goals is presented in Fig. 5, and goal realization is presented in Fig. 6.

External validity

In Table 6, the correlations between goal importance/goal realization with higher-order values, and relationship satisfaction are presented. The correlations are followed by Z-scores (Lee and Preacher 2013; Steiger 1980) representing the significance of the difference between correlations for goal importance with the external variable (higher-order values and relationship satisfaction) and goals realization with these variables.

The correlations presented in Table 6 leads to the following conclusions:

-

1)

All expectations regarding positive correlations (rectangle with solid lines in Table 6) and negative correlations (rectangles with the dotted line in Table 6) between marital goal importance and preferences for higher-order values were confirmed. In particular, the stable relationship and mutual support dimensions are positively correlated with self-transcendence and negatively with self-enhancement; conversely, the instrumental benefits and personal autonomy protection dimensions are positively correlated with self-enhancement and negatively with self-transcendence. The personal growth and varied lifestyle dimensions are positively correlated with openness to change and negatively with conservation; conversely, the submitting to norms and submitting to the partner dimensions are positively correlated with conservation and negatively with openness to change.

-

2)

All of the significant differences between (a) goal importance with higher-order values correlations and (b) goal realization with higher-order values correlations were in the hypothesized direction: The larger correlations were between goals importance and higher order values.

-

3)

All expectations regarding positive correlations (rectangle with solid lines in Table 6) and negative correlations (rectangles with the dotted line in Table 6) between marital goals realization and relationship satisfaction were confirmed. In particular, realizing goals related to relationship commitment (presented on the right side in Fig. 4) was positively correlated with relationship satisfaction, while realizing goals related to relationship avoidance (presented on the right side in Fig. 4) was negatively correlated with relationship satisfaction.

-

4)

All significant differences between (a) goal importance with relationship satisfaction correlations and (b) goal realization with relationship satisfaction correlations were in the hypothesized direction: The larger correlations were between goals realization and relationship satisfaction.

Discussion

We presented two studies aimed at developing a model of marital goals, referencing both the hierarchy of the importance of goals for each partner and the goals realized in the current relationship. The model was inspired by Schwartz’s (Schwartz 1992; Schwartz et al. 2012) value model, which defines values in terms of transsituational goals. We translated the abstract goals from the value model into marital goals and developed a model with eight categories of goals that form a circular structure such that similar goals are adjacent to each other and opposing goals are on the opposite sides of the circle. The measurement model of the questionnaire fit the data well, the structural model of the circular arrangement of the goal types was conformed, as well as the theoretically predicted relations between goals (importance and realization) with value-preferences and relationship satisfaction.

Marital goals are organized by two dimensions: oneself versus other focus and relationship commitment versus avoidance. The dimension oneself versus other focus corresponds to the personal- versus social-focus dimensions of Schwarz’s circular model. The goals of the oneself focus refer to using the relationship for self-realization (individualistic categories, emphasis on “me”); the goals of the other focus refer to the individual’s care for the well-being of the relationship and the partner (collective categories, emphasis on “us”). This dimension is similar to that from the theory by Canevello and Crocker (2015) describing partnership goals as placed on the dimension: toward others (compassionate goals) - toward oneself (self-image goals).

The second dimension, relationship avoidance versus relationship commitment, may be interpreted in terms of the fear (avoidance) of entering a relationship versus entering a relationship with trust and a sense of safety. It is analogous but not identical to the protection versus growth dimension of values in the Schwartz (Schwartz 1992, Schwartz et al. 2012) model. It may be similar to the approach-avoidance relationship goals described by Gable and Impett (2012). According to this dimension, using relationships to realize instrumental benefits (e.g., career development) or to meet social and/or familial expectations may be based on fear and cause the avoidance of closeness in a relationship. Submitting to the partner and preserving individual autonomy can be two sides of the same coin, (that is - real closeness avoidance) and they may differ in terms of a oneself versus other focus. Individuals who have difficulties with closeness are afraid to lose their autonomy and are overprotective of it, fearing their partner’s influence and trying to safeguard themselves against what in their mind is the dangerous influence of another person on their life (Bartholomew et al. 2001). The second type of relationship fear response is symbiosis and withdrawal, based on blurring one’s boundaries and submitting to the partner in a romantic relationship, which can only be considered a superficial closeness. Both overly rigid boundaries in a relationship (an excessive drive toward autonomy) and a lack of boundaries (excessive concession and adjustment) indicate the same problem – the inability to build actual closeness based on flexible boundaries between partners (Bengtson et al. 2005).

An authentic closeness and a lack of fear in a relationship with a partner means preserving personal identity, avoiding dependency on one’s partner, paying attention to the partner’s needs and freely submitting to his or her influence. It involves becoming to be without fear of experiencing closeness without losing one’s sense of self. According to this premise, the relationship commitment dimension encompasses goals belonging to the stable relationship group (safety in a relationship), personal growth for both partners, mutual support and trust and a varied lifestyle (shared enjoyment and openness to experiencing new things).

The dimension relationship avoidance versus relationship commitment in our model resembles the dimensions of anxiety versus avoidance described in the research on adult attachment - where relationship avoidance would be related to anxiety dimension of attachment while relationship commitment would be negatively related to avoidance dimension (see review by Mikulincer and Shaver 2007). Some research shows that people who are high on attachment anxiety in their marriage want to pursue goals that focus on avoiding negative outcomes (e.g. conflict, losing a partner) and increasing intimacy with their partner (Impett and Gordon 2010; Impett et al. 2008; Impett and Peplau 2002). The goal of the attachment system is to maintain the feeling of security and this is true of both approaching and avoiding strategies. Attachment can be seen as a pattern of behavioral, emotional, and cognitive elements describing the relation to the partner. Personal expectations regarding the partner in a marriage or relationship may be an important component of this pattern and our model described these expectations - marital goals in a comprehensive way. Marital goals can be seen as rooted in the early experiences that shape attachment styles, however at the same time are cognitively available to people and can be a point of departure in interventions aimed at improving the relationship.

Both the similarity of marital goals between partners and the realization of these goals can be crucial for the explanation of marital satisfaction in future research. According to many studies, partners in a relationship are more similar in terms of personality, interests, and gender roles than randomly formed couples (Gonzaga et al. 2007; Houts et al. 1996; Merikangas 1982). Most studies support the hypothesis that similarities in terms of qualities (especially personal qualities) are related to marriage satisfaction (Gaunt 2006; Luo and Klohnen 2005). Though some studies support the complementarity hypothesis that marriage satisfaction occurs when partners differ from each other (Luo et al. 2008). The model proposed in this research enables the study of similarity in terms of marital goals importance as well as realization, which is a significant factor that also influences marital satisfaction. In the same way that the ability of an individual to fulfill high priority goals is vital for personal well-being (Ostermann et al. 2017; Sortheix and Schwartz 2017), meeting relationship goals by each of the partners is key to attaining marriage satisfaction.

This study is not free from limitations. We proposed a model with eight marital goals located in the circular space shaped by two basic dimensions. However, future research may also propose other goals. According to the claims of our model, other goals should be possible to locate within the circular space (e.g., power goals, Simpson et al. 2015). According to our model, one could expect that power goals may be an aspect of instrumental benefits, built on the self-enhancement values from Schwartz’s model (Schwartz et al. 2012) where power values belongs. However, such considerations still need empirical verification. The study was self-reported and was conducted in a Polish sample. Further research should be conducted with respect to other cultures as well. Moreover, the study focused on current marital goals and did not consider their dynamic nature. If further research is conducted, analyzing marital goals in a longitudinal framework would be effective. Marital goals are formed in pairs, so the interdependency and dyadic nature of the data also has to be considered in future research.

References

Bartholomew, K., Kwong, M. J., & Hart, S. D. (2001). Attachment. In W. J. Livesley (Ed.), Handbook of personality disorders: Theory, research, and treatment (pp. 196–230). New York: The Guilford Press.

Bengtson, V. L., Acock, A. C., Allen, K. R., Dilworth-Anderson, P., & Klein, D. M. (2005). Sourcebook of family theory and research. Sage Publications.

Brunstein, J. C., Dangelmayer, G., & Schultheiss, O. C. (1996). Personal goals and social support in close relationships: Effects on relationship mood and marital satisfaction. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 71(5), 1006–1019.

Campbell, L., Simpson, J. A., Kashy, D. A., & Fletcher, G. J. O. (2001). Ideal standards, the self, and flexibility of ideals in close relationships. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 27(4), 447–462. https://doi.org/10.1177/0146167201274006 .

Canevello, A., & Crocker, J. (2010). Creating good relationships: Responsiveness, relationship quality, and interpersonal goals. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 99(1), 78–106. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0018186 .

Canevello, A., & Crocker, J. (2011). Changing relationship growth belief: Intrapersonal and interpersonal consequences of compassionate goals. Personal Relationships, 18(3), 370–391. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1475-6811.2010.01296.x .

Canevello, A., & Crocker, J. (2015). How interpersonal goals shape intrapsychic experiences: Self-image and compassionate goals and feeling uneasy or at ease with others. Social and Personality Psychology Compass, 9(11), 620–629. https://doi.org/10.1111/spc3.12206 .

Canevello, A., Granillo, M. T., & Crocker, J. (2013). Predicting change in relationship insecurity: The roles of compassionate and self-image goals. Personal Relationships, 20(4), 587–618. https://doi.org/10.1111/pere.12002 .

Cieciuch, J. (2017). Multidimensional scaling (MDS). In V. Zeigler-Hill, & T. Shackelford (Eds.), Encyclopedia of Personality and Individual Differences (pp. 1–4). Springer International Publishing AG. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-28099-8_1329-1 .

Cieciuch, J., & Schwartz, S. H. (2012). The number of distinct basic values and their structure assessed by PVQ-40. Journal of Personality Assessment, 94(3), 321–328. https://doi.org/10.1080/00223891.2012.655817 .

Crocker, J., & Canevello, A. (2008). Creating and undermining social support in communal relationships: The role of compassionate and self-image goals. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 95(3), 555–575. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.95.3.555 .

Dainton, M. (2000). Maintenance behaviors, expectations for maintenance, and satisfaction: Linking comparison levels to relational maintenance strategies. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, 17(6), 827–842. https://doi.org/10.1177/0265407500176007 .

Davidov, E., Schmidt, P., & Schwartz, S. H. (2008). Bringing values back in. The adequacy of the European social survey to measure values in 20 countries. Public Opinion Quarterly, 72(3), 420–445. https://doi.org/10.1093/poq/nfn035 .

Elliot, A. J. (1997). Integrating the classic and contemporary approaches to achievement motivation: A hierarchical model of approach and avoidance achievement motivation. In M. Maehr & P. Pintrich (Eds.), Advances in motivation and achievement (pp. 243–279). Greenwich: CT: JAI Press.

Fitzsimons, G. M., & Shah, J. Y. (2008). How goal instrumentality shapes relationship evaluations. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 95(2), 319–337. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.95.2.319 .

Fletcher, G. J. O., Simpson, J. A., & Thomas, G. (2000). Ideals, perceptions, and evaluations in early relationship development. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 79(6), 933–940. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.79.6.933 .

Gable, S. J., & Impett, E. A. (2012). Approach and avoidance motives and close relationships. Social and Personality Psychology Compass, 6(1), 95–108. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1751-9004.2011.00405.x .

Gaunt, R. (2006). Couple similarity and marital satisfaction: Are similar spouses happier? Journal of Personality, 74(5), 1401–1420. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-6494.2006.00414.x .

Gonzaga, G. C., Campos, B., & Bradbury, T. (2007). Similarity, convergence, and relationship satisfaction in dating and married couples. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 93(1), 34–48. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.93.1.34 .

Higgins, E. T. (1998). Promotion and prevention: Regulatory focus as a motivational principle. Advances in Experimental Social Psychology, 30, 1–46. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0065-2601(08)60381-0 .

Houts, R. M., Robins, E., & Huston, T. L. (1996). Compatibility and the development of premarital relationships. Journal of Marriage and Family, 58(1), 7–20. https://doi.org/10.2307/353373 .

Impett, E. A., & Gordon, A. (2010). Why do people sacrifice to approach rewards versus to avoid costs? Insights from attachment theory. Personal Relationships, 17, 299–315. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1475-6811.2010.01277.x .

Impett, E. A., & Peplau, L. A. (2002). Why some women consent to unwanted sex with a dating partner: Insights from attachment theory. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 26, 359–369. https://doi.org/10.1111/1471-6402.t01-1-00075 .

Impett, E. A., Gordon, A., & Strachman, A. (2008). Attachment and daily sexual goals: A study of dating couples. Personal Relationships, 15, 375–390. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1475-6811.2008.00204.x .

Kelley, D. L., & Burgoon, J. K. (1991). Understanding marital satisfaction and couple type as functions of relational expectations. Human Communication Research, 18(1), 40–69. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2958.1991.tb00528.x .

Kruglanski, A. W. (1996). Goals as knowledge structures. In P. M. Gollwitzer & J. A. Bargh (Eds.), The psychology of action (pp. 599–618). New York: Guilford Press.

Kruglanski, A. W., Shah, Y. J., Fishbach, A., Friedman, R., Chun, W. Y., & Sleeth-Keppler, D. (2002). A theory of goal-systems. In M. P. Zanna (Ed.), Advances in experimental social psychology (pp. 331–376). San Diego: Academic Press.

Lee, I. A., & Preacher, K. J. (2013, September). Calculation for the test of the difference between two dependent correlations with one variable in common [Computer software]. Available from http://quantpsy.org.

Lewis, M. (1990). The development of intentionality and the role of consciousness. Psychological Inquiry, 1(3), 231–247. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15327965pli0103_13 .

Li, T., & Fung, H. (2011). The dynamic goal theory of marital satisfaction. Review of General Psychology, 15(3), 246–254. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0024694 .

Light, A. E., & Fitzsimons, G. M. (2014). Contextualizing marriage as a means and a goal. Psychological Inquiry, 25, 88–94. https://doi.org/10.1080/1047840X.2014.878522 .

Luo, S., & Klohnen, E. C. (2005). Assortative mating and marital quality in newlyweds: A couple-centered approach. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 88(2), 304–326. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.88.2.304 .

Luo, S., Chen, H., Yue, G., Zhang, G., Zhaoyang, R., & Xu, D. (2008). Predicting marital satisfaction from self, partner, and couple characteristics: Is it me, you, or us? Journal of Personality, 76(5), 1231–1266. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-6494.2008.00520.x .

Merikangas, K. R. (1982). Assortative mating for psychiatric disorders and psychological traits. Archives of General Psychiatry, 39(10), 1173–1180. https://doi.org/10.1001/archpsyc.1982.04290100043007 .

Mikulincer, M., & Shaver, P. R. (2007). Attachment in adulthood: Structure, dynamics, and change. New York: Guilford Press.

Moskowitz, G. B., & Grant, H. (2009). The psychology of goals. New York: Guilford Press.

Norton, R. (1983). Measuring marital quality: A critical look at the dependent variable. Journal of Marriage and the Family, 45(1), 141–151. https://doi.org/10.2307/351302 .

Ostermann, M., Huffziger, S., Kleindienst, N., Mata, J., Schmahl, C., Beierlein, C., Bohus, M., & Lyssenko, L. (2017). Realization of personal values predicts mental health and satisfaction with life in a German population. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology, 36(8), 651–674. https://doi.org/10.1521/jscp.2017.36.8.651 .

Pinsof, W. M., & Lebow, J. L. (2005). Family psychology. The art of science. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Sagiv, L., Roccass, S., Cieciuch, J., & Schwartz, S. (2017). Personal values in human life. Nature Human Behaviour, 1, 630–639. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41562-017-0185-3 .

Schwartz, S. H. (1992). Universals in the content and structure of values: Theory and empirical tests in 20 countries. In M. Zanna (Ed.), Advances in experimental social psychology (pp. 1–65). New York: Academic Press.

Schwartz, S. H. (2017). The refined theory of basic values. In S. Roccas & L. Sagiv (Eds.), Values and behavior: Taking a cross-cultural perspective (pp. 51–72). Cham: Springer International Publishing.

Schwartz, S. H., & Cieciuch, J. (2016). Values. In F. T. L. Leong, D. Bartram, F. Cheung, K. F. Geisinger, & D. Iliescu (Eds.), The ITC international handbook of testing and assessment (pp. 106–119). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Schwartz, S. H., Cieciuch, J., Vecchione, M., Davidov, E., Fischer, R., Beierlein, C., Ramos, A., Verkasalo, M., Lönnqvist, J.-E., Demirutku, K., Dirilen-Gumus, O., & Konty, M. (2012). Refining the theory of basic individual values. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 103(4), 663–688. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0029393 .

Schwartz, H. S., Cieciuch, J., Vecchione, M., Torres, C., Dirilem-Gumus, O., & Butenko, T. (2017). Value tradeoffs propel and inhibit behavior: Validating the 19 refined values in four countries. European Journal of Social Psychology, 47(3), 241–258. https://doi.org/10.1002/ejsp.2228 .

Simpson, J. A., Farrell, A. K., Oriña, M. M., & Rothman, A. J. (2015) Power and social influence in relationships. Editors-in-chief: M. Mikulincer and P. R. Shaver, APA Handbook of Personality and Social Psychology: Vol. 3. Interpersonal Relations (pp. 393-420). American Psychological Association.

Sortheix, F. M., & Schwartz, S. H. (2017). Values that underlie and undermine well-being: Variability across countries. European Journal of Personality, 31(2), 187–201. https://doi.org/10.1002/per.2096 .

Steiger, J. H. (1980). Tests for comparing elements of a correlation matrix. Psychological Bulletin, 87, 245–251.

Strus, W., & Cieciuch, J. (2017). Towards a synthesis of personality, temperament, motivation, emotion and mental health models within the Circumplex of personality Metatraits. Journal of Research in Personality, 66, 70–95. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrp.2016.12.002 .

Funding

The work of Anna Czyżkowska was supported by Grants 2014/13/B/HS6/03947 from the Polish National Science Centre. The work of Jan Cieciuch was supported by the University Research Priority Program Social Networks of the University of Zurich.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

On behalf of all authors, the corresponding author states that there is no conflict of interest.

Ethical Approval

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Informed Consent

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Czyżkowska, A., Cieciuch, J. Marital goals: Circular value-based model and measurement. Curr Psychol 41, 3401–3417 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-020-00787-0

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-020-00787-0