Abstract

The present paper examines the wage effects of continuous training programs using individual-level data from the German Socio Economic Panel (GSOEP). In order to account for selectivity in training participation we estimate average treatment effects (ATE and ATT) of general and firm-specific continuous training programs using several state-of-the-art propensity score matching (PSM) estimators. Additionally, we also apply a combined matching difference-in-differences (MDiD) estimator to account for unobserved individual characteristics (e.g. motivation, ability). While the estimated ATE and ATT for general training are significant ranging between about 4 and 7.5%, the corresponding wage effects of firm-specific training are mostly insignificant. Using the more appropriate MDiD estimator, however, we find a more precise and highly significant wage effect of about 5–6%, though only for general training and not for firm-specific training. These results are consistent with standard human capital theory insofar as general training is associated with larger wage increases than firm-specific training. Furthermore, we conclude that firms may intend to use specific training to adjust to new job requirements, while career-relevant changes may be conditioned to general training.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

The terms ‘training’ and ‘continuous training’ are used synonymously in this paper. By continuous training we mean the individual’s participation in job-related courses and seminars. These courses and seminars are either conducted internally (i.e. within the firm) or outside by external institutions and providers. Some examples of possible training measures are language courses, courses for improving technical skills, and computer courses.

Sometimes the estimated wage effects of continuous training appear to be quite unrealistic with respect to magnitude ranging from −62.5 to 52.9% (see e.g. Budria and Pereira 2004).

See Loewenstein and Spletzer (1999) for an analogous approach using data from the National Longitudinal Survey of the Youth (NLSY).

However, we use the data of the least recent training course in one of our robustness checks in Sect. 4.

We use the natural logarithm of this income and exclude responses below 600 Euros to avoid implausible information in our sample of full-time employed males.

The results remain unchanged when using educational degree instead of years of schooling.

In the standard Mincer wage function, log wages is regressed on education and job experience (original and squared observations). The Mincer wage function is based upon the schooling function that assumes an exponential relation between wages and the years of schooling. For further details, see Mincer (1974), Chiswick (2003), and Heckman et al. (2006).

We use tenure instead of total working experience. The reason for this proceeding is that experience cannot directly be observed in our data. We would have to approximate experience by individual’s age minus years of schooling minus 6 (the age at which children usually start schooling in Germany), which is a relatively imprecise measure of effective working experience.

In our analysis, we use kernel weights to account for the closeness in outcomes of participants and non-participants.

Re-weighting is necessary if the group of the treated individuals is larger than the group of controls due to oversampling of treated individuals. As this is not the case in our GSOEP data, we do not re-weight the sample.

The question of whether all or almost all individuals in the control group are used depends on the choice of the kernel function (Calienedo and Kopeinig 2006).

This bias does not completely diminish because due to unobserved characteristics training participants and non-participants are selected groups earning different wages, even in the absence of continuous training programs.

We performed robustness checks on that. See Sect. 4 for details.

The effects of the sector and regional dummies are not displayed in the Appendix. They are available from the authors upon request. Both sets of dummies show mostly insignificant coefficients.

The fact that we observe relatively volatile wage effects of our measures for continuous training (and schooling), while the coefficients for our control variables remain quite stable in different model specifications, may not solely indicate an omitted variables bias. It can also be viewed as an indication for a selectivity bias.

HS is a dummy variable, which equals one when the individual executes high-skilled white collar work or managerial activities. The variable SK equals one if the individual executes skilled blue or white collar work. The reference category is US which is equal to one if the individual executes unskilled blue or white collar work.

The variable we use to get this information is the same as in the 2004 questionnaire. See Sect. 2 for details. We again regard individuals as participants in continuous training when they stated to have participated in professionally oriented courses.

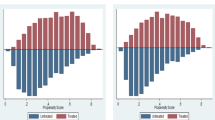

Plotting the density of the propensity score distribution reveals that the treated and control individuals differ. Especially in the higher propensity scores we have a quite substantial amount of treated observations but relatively few controls. Nevertheless, we can assure common support.

The matched non-participants are drawn by performing the nearest neighbour matching as before (four nearest neighbours, replacement) for our three variables of interest.

Alternatively, one may argue that differences in prosperity between firms affect their motivation to provide general or firm-specific training. Specifically, general training may be more likely to be offered by prosperous firms (e.g. as a kind of bonus), while firm-specific training may be offered by firms regardless whether they prosper or not. As a consequence, prosper firms offering general training may be more likely to pay higher wages than less prosper firms, which tend to offer firm-specific training. Although we are not able to explicitly control for establishment prosperity, we address this issue indirectly by controlling for firm size and regional affiliation.

We decided not to use the first training course respondents could name, neither for the analysis nor for the sensitivity check. Here, the individuals are explicitly asked for the most recent or current course and we do not expect to see wage effects from that training, mostly because of the fact that this course may just have been finished or might even last.

References

Abadie A, Imbens GW (2002) Simple and bias-corrected matching estimators. NBER Technical Working Paper No. 0283, Cambridge, MA

Abadie A, Drukker D, Leber Herr J, Imbens GW (2004) Implementing matching estimators for average treatment effects in Stata. Stata J 1:1–18

Acemoglu D, Pischke J-S (1998) Why do firms train? Theory and evidence. Q J Econ 113:79–119

Acemoglu D, Pischke J-S (1999a) Beyond Becker: training in imperfect labour markets. Econ J 109:F112–F142

Acemoglu D, Pischke J-S (1999b) The structure of wages and investment in general training. J Polit Econ 107:539–572

Arulampalam W, Booth A (2001) Learning and earning: do multiple training events pay? A decade of evidence from a cohort of young British men. Economica 68:379–400

Ashenfelter O (1978) Estimating the effect of training program on earnings. Rev Econ Stat 60:47–57

Ashenfelter O, Card D (1985) Using the longitudinal structure of earnings to estimate the effect of training programs. Rev Econ Stat 67:648–660

Becker GS (1962) Investment in human capital: a theoretical analysis. J Polit Econ 70(suppl):9–49

Bishop J (1997) What we know about employer-provided training: a review of the literature. Res Labor Econ 16:19–87

Blundell R, Dearden L, Meghir C (1996) The determinants and effects of work-related training in Britain. Institute of Fiscal Studies, London

Blundell R, Dearden L, Meghir C (1999) Work-related training and earnings. Mimeo, Institute of Fiscal Studies

Blundell R, Costa Dias M (2002) Alternative approaches to evaluation in empirical microeconomics. Portuguese Econ J 1:91–115

Blundell R, Dearden L, Sianesi B (2005) Evaluating the effect of education on earnings: models, methods and results from the National Child Development Survey. J R Stat Soc Ser A 168:473–512

Booth A (1991) Job-related formal training: who receives it and what is it worth? Oxf Bull Econ Stat 53:281–294

Booth A (1993) Private sector training and graduate earnings. Rev Econ Stat 75:164–170

Booth AL, Bryan ML (2005) Testing some predictions of human capital theory: new training evidence from Britain. Rev Econ Stat 87:391–394

Büchel F, Pannenberg M (2004) Berufliche Weiterbildung in West und Ostdeutschland—Teilnehmer, Struktur und individueller Ertrag. Zeitschrift für Arbeitsmarktforschung 37:73–126

Budria S, Pereira PT (2004) On the returns to training in Portugal. IZA Discussion Paper No. 1429, Bonn

Caliendo M, Hujer R (2006) The microeconometric estimation of treatment effects—an overview. J Ger Stat Soc All Stat Arch 90:197–212

Caliendo M, Kopeinig S (2006) Some practical guidance for the implementation of propensity score matching. J Econ Surv (forthcoming)

Cameron AC, Trivedi PK (2005) Microeconometrics: methods and applications. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge

Chiswick BR (2003) Jacob Mincer, experience and the distribution of earnings. Rev Econ Household 1:343–361

Düll H, Bellmann L (1999) Der unterschiedliche Zugang zur betrieblichen Weiterbildung nach Qualifikation und Berufsstatus: Eine Analyse auf der Basis des IAB-Betriebspanels 1997 für West- und Ostdeutschland. Mitteilungen aus der Arbeitsmarkt- und Berufsforschung 32:70–84

Frazis H, Loewenstein M (2003) Re-examining the returns to training: functional form, magnitude, and interpretation. Working Paper 367, Bureau of Labor Statistics

Garloff A, Kuckulenz A (2006) Training, mobility, and wages: specific versus general human capital. Jahrbücher für Nationalökonomie und Statistik 226/1:55–81

Gerfin M (2004) Work-related training and wages: an empirical analysis for male workers in Switzerland. IZA Discussion Paper No. 1078, Bonn

Gerfin M, Leu RE, Nyffeler R (2003) Berufliche Weiterbildung in der Schweiz. Diskussionspapier 03-18, Universität Bern, Volkswirtschaftliches Institut

Goux D, Maurin E (2000) Returns to firm-provided training: Evidence from French worker-firm matched data. Labour Econ 7:1–19

Haisken-DeNew J, Frick J (2005) DTC—Desktop companion to the German Socio Economic Panel (GSOEP), Deutsches Institut für Wirtschaftsforschung, Berlin

Heckman JJ, Ichimura H, Todd PE (1997) Matching as an econometric evaluation estimator: evidence from evaluating a job training program. Rev Econ Stud 64:605–654

Heckman JJ, Ichimura H, Smith JA, Todd P (1998) Characterizing selection bias using experimental data. Econometrica 65:1017–1098

Heckman JJ, LaLonde RJ, Smith JA (1999) The economics and econometrics of active labor market programs. In: Ashenfelter O, Card D (eds) Handbook of labor economics, vol 3A. Elsevier, Amsterdam, pp 1865–2097

Heckman JJ, Lochner L, Todd PE (2006) Earnings functions, rate of return and treatment effects: The Mincer equation and beyond. In: Hanushek E, Welch F (eds) Handbook of economics and education. Elsevier, North-Holland, Amsterdam, pp 307–458

Jürges H, Schneider K (2006) Dynamische Lohneffekte beruflicher Weiterbildung. In: Weiss M (Hrsg.) Tagungsband des Bildungsökonomischen Ausschusses des Verein für Socialpolitik 2004/2005. Duncker & Humblodt, Berlin

Krueger A, Rouse C (1998) The effect of workplace education on earnings, turnover, and job performance. J Labor Econ 16:61–94

Kuckulenz A, Maier M (2006) Heterogeneous returns to training. Jahrbücher für Nationalökonomie und Statistik 226/1:24–40

Kuckulenz A, Zwick T (2003) The impact of training on earnings—differences between participant groups and training forms. ZEW Discussion Paper No. 03-57, Mannheim

Kuckulenz A, Zwick T (2005) Heterogene Einkommenseffekte betrieblicher Weiterbildung. Die Betriebswirtschaft 65:258–275

Lechner M (1998) Training the East German labor force: microeconometric evaluations of continuous vocational training after unification. Physica, Heidelberg

Leuven E (2004) A review of the wage returns to private sector training. Paper presented at the EC–OECD Seminar on Human Capital and Labour Market Performance: Evidence and Policy Challenges. Brussels, December 8th

Leuven E (2005) The economics of private sector training: a survey of the literature. J Econ Surv 19:91–111

Leuven E, Oosterbeek H (2002) A new approach to estimate the wage returns to work-related training. IZA Discussion Paper No. 526, Bonn

Loewenstein MA, Spletzer JR (1998) Dividing the costs and returns to general training. J Labor Econ 16:142–171

Loewenstein MA, Spletzer JR (1999) General and specific training: evidence and implications. J Hum Res 34:710–733

Lynch L (1992) Private sector training and the earnings of young workers. Am Econ Rev 82:299–312

Mincer J (1974) Schooling, experience, and earnings. National Bureau of Economic Research, New York

Mooney CZ, Duval RD (1993) Bootstrapping: a nonparametric approach to statistical inference. Sage, Newbury Park

Pannenberg M (1997) Financing on-the-job-training: shared investment or promotion based systems? Evidence from Germany. Zeitschrift für Wirtschafts und Sozialwissenschaften 117:525–543

Parent D (1999) Wages and mobility: the impact of employer-provided training. J Labor Econ 17:298–317

Parent D (2003) Employer-supported training in Canada and its impact on mobility and wages. Empir Econ 28:431–459

Pischke J-S (2001) Continuous training in Germany. J Popul Econ 14:523–548

Rosenbaum P, Rubin D (1983) The central role of the propensity score in observational studies for causal effects. Biometrika 70:41–50

Schøne P (2002) Why is the return to training so high? Mimeo, Institute for Social Research, Oslo, Norway

Schøne P (2004) Firm-financed training: firm specific or general skills? Empir Econ 29:885–900

Smith H (1997) Matching with multiple controls to estimate treatment effects in observational studies. Sociol Methodol 27:325–353

Veum JR (1995) Sources of training and their impact on wages. Ind Labor Relat Rev 48:812–826

Acknowledgments

The authors gratefully acknowledge financial support from the German Research Foundation (DFG). In addition, we have benefited a lot from the discussions with Andreas Ammermueller, Todd Bradley, Bernd Fitzenberger, Dietmar Harhoff, Olaf Huebler, Eva Muthmann, and Stephan Lothar Thomsen whose suggestions have been of great value. We are also indebted to Todd Bradley for improving our English. Any remaining errors are, of course, our own.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Appendix

Appendix

Yearly wage development of training participants, non-participants and matched controls. Note The matched non-participants are drawn from the nearest neighbour matching for CT, allowing for replacement and using the four closest matches. Source German Socio Economic Panel (waves 1997–2004), own calculations

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Muehler, G., Beckmann, M. & Schauenberg, B. The returns to continuous training in Germany: new evidence from propensity score matching estimators. RMS 1, 209–235 (2007). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11846-007-0014-6

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11846-007-0014-6

Keywords

- Continuous training

- Wage effect

- Average treatment effect

- Selectivity bias

- Propensity score matching estimators

- Combined matching difference-in-differences estimator