Abstract

Purpose

Following colorectal cancer diagnosis and anti-cancer therapy, declines in cardiorespiratory fitness and body composition lead to significant increases in morbidity and mortality. There is increasing interest within the field of exercise oncology surrounding potential strategies to remediate these adverse outcomes. This study compared 4 weeks of moderate-intensity exercise (MIE) and high-intensity exercise (HIE) training on peak oxygen consumption (V̇O2peak) and body composition in colorectal cancer survivors.

Methods

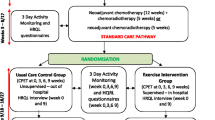

Forty seven post-treatment colorectal cancer survivors (HIE = 27 months post-treatment; MIE = 38 months post-treatment) were randomised to either HIE [85–95 % peak heart rate (HRpeak)] or MIE (70 % HRpeak) in equivalence with current physical activity guidelines and completed 12 training sessions over 4 weeks.

Results

HIE was superior to MIE in improving absolute (p = 0.016) and relative (p = 0.021) V̇O2peak. Absolute (+0.28 L.min−1, p < 0.001) and relative (+3.5 ml.kg−1.min−1, p < 0.001) V̇O2 peak were increased in the HIE group but not the MIE group following training. HIE led to significant increases in lean mass (+0.72 kg, p = 0.002) and decreases in fat mass (−0.74 kg, p < 0.001) and fat percentage (−1.0 %, p < 0.001), whereas no changes were observed for the MIE group. There were no severe adverse events.

Conclusions

In response to short-term training, HIE is a safe, feasible and efficacious intervention that offers clinically meaningful improvements in cardiorespiratory fitness and body composition for colorectal cancer survivors.

Implications for Cancer Survivors

HIE appears to offer superior improvements in cardiorespiratory fitness and body composition in comparison to current physical activity recommendations for colorectal cancer survivors and therefore may be an effective clinical utility following treatment.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Ferlay J, Soerjomataram I, Dikshit R, Eser S, Mathers C, Rebelo M, et al. Cancer incidence and mortality worldwide: sources, methods and major patterns in GLOBOCAN 2012. Int J Cancer J Int Cancer. 2015;136(5):E359–86. doi:10.1002/ijc.29210.

Jones LW, Peppercorn J. Exercise research: early promise warrants further investment. Lancet Oncol. 2010;11(5):408–10. doi:10.1016/S1470-2045(10)70094-2.

Lakoski SG, Eves ND, Douglas PS, Jones LW. Exercise rehabilitation in patients with cancer. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 2012;9(5):288–96. doi:10.1038/nrclinonc.2012.27.

Lakoski SG, Willis BL, Barlow CE, et al. Midlife cardiorespiratory fitness, incident cancer, and survival after cancer in men: The Cooper Center longitudinal study. JAMA Oncol. 2015. doi:10.1001/jamaoncol.2015.0226.

Zhang P, Sui X, Hand GA, Hebert JR, Blair SN. Association of changes in fitness and body composition with cancer mortality in men. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2014;46(7):1366–74. doi:10.1249/mss.0000000000000225.

Farrell SW, Finley CE, McAuley PA, Frierson GM. Cardiorespiratory fitness, different measures of adiposity, and total cancer mortality in women. Obesity (Silver Spring, Md). 2011;19(11):2261–7. doi:10.1038/oby.2010.345.

Schmid D, Leitzmann MF. Cardiorespiratory fitness as predictor of cancer mortality: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Ann Oncol : Off J Eur Soc Med Oncol / ESMO. 2015;26(2):272–8. doi:10.1093/annonc/mdu250.

West MA, Lythgoe D, Barben CP, Noble L, Kemp GJ, Jack S, et al. Cardiopulmonary exercise variables are associated with postoperative morbidity after major colonic surgery: a prospective blinded observational study. Br J Anaesth. 2014;112(4):665–71. doi:10.1093/bja/aet408.

West MA, Parry MG, Lythgoe D, Barben CP, Kemp GJ, Grocott MP, et al. Cardiopulmonary exercise testing for the prediction of morbidity risk after rectal cancer surgery. Br J Surg. 2014;101(9):1166–72. doi:10.1002/bjs.9551.

West MA, Loughney L, Barben CP, Sripadam R, Kemp GJ, Grocott MP, et al. The effects of neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy on physical fitness and morbidity in rectal cancer surgery patients. Eur J Surg Oncol : J Eur Soc Surg Oncol Br Assoc Surg Oncol. 2014;40(11):1421–8. doi:10.1016/j.ejso.2014.03.021.

West MA, Loughney L, Lythgoe D, Barben CP, Adams VL, Bimson WE, et al. The effect of neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy on whole-body physical fitness and skeletal muscle mitochondrial oxidative phosphorylation in vivo in locally advanced rectal cancer patients—an observational pilot study. PLoS One. 2014;9(12), e111526. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0111526.

Fearon K, Arends J, Baracos V. Understanding the mechanisms and treatment options in cancer cachexia. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 2013;10(2):90–9. doi:10.1038/nrclinonc.2012.209.

Aoyagi T, Terracina KP, Raza A, Matsubara H, Takabe K. Cancer cachexia, mechanism and treatment. World J Gastrointest Oncol. 2015;7(4):17–29. doi:10.4251/wjgo.v7.i4.17.

Fearon K, Strasser F, Anker SD, Bosaeus I, Bruera E, Fainsinger RL, et al. Definition and classification of cancer cachexia: an international consensus. Lancet Oncol. 2011;12(5):489–95. doi:10.1016/S1470-2045(10)70218-7.

Thoresen L, Frykholm G, Lydersen S, Ulveland H, Baracos V, Prado CMM, et al. Nutritional status, cachexia and survival in patients with advanced colorectal carcinoma. Different assessment criteria for nutritional status provide unequal results. Clin Nutr. 2013;32(1):65–72. doi:10.1016/j.clnu.2012.05.009.

Prado CM, Lieffers JR, McCargar LJ, Reiman T, Sawyer MB, Martin L, et al. Prevalence and clinical implications of sarcopenic obesity in patients with solid tumours of the respiratory and gastrointestinal tracts: a population-based study. Lancet Oncol. 2008;9(7):629–35. doi:10.1016/s1470-2045(08)70153-0.

Alves CR, da Cunha TF, da Paixao NA, Brum PC. Aerobic exercise training as therapy for cardiac and cancer cachexia. Life Sci. 2015;125:9–14. doi:10.1016/j.lfs.2014.11.029.

Weston KS, Wisloff U, Coombes JS. High-intensity interval training in patients with lifestyle-induced cardiometabolic disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Br J Sports Med. 2013. doi:10.1136/bjsports-2013-092576.

Sellar CM, Bell GJ, Haennel RG, Au HJ, Chua N, Courneya KS. Feasibility and efficacy of a 12-week supervised exercise intervention for colorectal cancer survivors. Appl Physiol Nutr Meta. 2014;39(6):715–23. doi:10.1139/apnm-2013-0367.

Hawkes AL, Chambers SK, Pakenham KI, Patrao TA, Baade PD, Lynch BM, et al. Effects of a telephone-delivered multiple health behavior change intervention (CanChange) on health and behavioral outcomes in survivors of colorectal cancer: a randomized controlled trial. J Clin Oncol : Off J Am Soc Clin Oncol. 2013;31(18):2313–21. doi:10.1200/jco.2012.45.5873.

Lynch BM, Baade P, Fritschi L, Leggett B, Owen N, Pakenham K, et al. Modes of presentation and pathways to diagnosis of colorectal cancer in Queensland. Med J Aust. 2007;186(6):288–91.

American College of Sports Medicine. ACSM’s guidelines for exercise testing and prescription. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2014.

Wasserman K, Hansen J, Sue D, Casaburi R, Whipp B. Principles of exercise testing and interpretation: including pathophysiology and clinical applications. Philadelphia: Wolters Kluwer Health/Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2012.

Borg GAV. Psychophysical bases of perceived exertion. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 1982;14(5):377–81. doi:10.1249/00005768-198205000-00012.

Godin G, Shephard RJ. A simple method to assess exercise behavior in the community. Can J Appl Sport Sci J Can Sci Appl Sport. 1985;10(3):141–6.

Miller DJ. Comparison of activity levels using the Caltrac accelerometer and five questionnaires. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 1994;26(3):376–82.

Rauh M, Hovell MF, Hofstetter CR, Sallis JF, Gleghorn A. Reliability and validity of self-reported physical activity in Latinos. Int J Epidemiol. 1992;21(5):966–71. doi:10.1093/ije/21.5.966.

Schmitz KH, Courneya KS, Matthews C, Demark-Wahnefried W, Galvao DA, Pinto BM, et al. American College of Sports Medicine roundtable on exercise guidelines for cancer survivors. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2010;42(7):1409–26. doi:10.1249/MSS.0b013e3181e0c112.

Buffart LM, Galvao DA, Brug J, Chinapaw MJ, Newton RU. Evidence-based physical activity guidelines for cancer survivors: current guidelines, knowledge gaps and future research directions. Cancer Treat Rev. 2014;40(2):327–40. doi:10.1016/j.ctrv.2013.06.007.

Courneya KS, Friedenreich CM, Quinney HA, Fields ALA, Jones LW, Fairey AS. A randomized trial of exercise and quality of life in colorectal cancer survivors. Eur J Cancer Care. 2003;12(4):347–57. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2354.2003.00437.x.

Pinto BM, Papandonatos GD, Goldstein MG, Marcus BH, Farrell N. Home-based physical activity intervention for colorectal cancer survivors. Psycho-Oncology. 2013;22(1):54–64. doi:10.1002/pon.2047.

Cramer H, Lauche R, Klose P, Dobos G, Langhorst J. A systematic review and meta-analysis of exercise interventions for colorectal cancer patients. Eur J Cancer Care (Engl). 2014;23(1):3–14. doi:10.1111/ecc.12093.

Halliwill JR, Sieck DC, Romero SA, Buck TM, Ely MR. Blood pressure regulation X: what happens when the muscle pump is lost? Post-exercise hypotension and syncope. Eur J Appl Physiol. 2014;114(3):561–78. doi:10.1007/s00421-013-2761-1.

Brito Ade F, de Oliveira CV, Santos Mdo S, Santos AC. High-intensity exercise promotes postexercise hypotension greater than moderate intensity in elderly hypertensive individuals. Clin Physiol Funct Imaging. 2014;34(2):126–32. doi:10.1111/cpf.12074.

Jordan J, Shannon JR, Black BK, Ali Y, Farley M, Costa F, et al. The pressor response to water drinking in humans: a sympathetic reflex? Circulation. 2000;101(5):504–9.

Endo MY, Kajimoto C, Yamada M, Miura A, Hayashi N, Koga S, et al. Acute effect of oral water intake during exercise on post-exercise hypotension. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2012;66(11):1208–13. doi:10.1038/ejcn.2012.139.

de Oliveira EP, Burini RC, Jeukendrup A. Gastrointestinal complaints during exercise: prevalence, etiology, and nutritional recommendations. Sports Med. 2014;44 Suppl 1:79–85. doi:10.1007/s40279-014-0153-2.

Bourke L, Thompson G, Gibson DJ, Daley A, Crank H, Adam I, et al. Pragmatic lifestyle intervention in patients recovering from colon cancer: a randomized controlled pilot study. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2011;92(5):749–55. doi:10.1016/j.apmr.2010.12.020.

Jones LW, Liang Y, Pituskin EN, Battaglini CL, Scott JM, Hornsby WE, et al. Effect of exercise training on peak oxygen consumption in patients with cancer: a meta-analysis. Oncologist. 2011;16(1):112–20. doi:10.1634/theoncologist.2010-0197.

Allgayer H, Nicolaus S, Schreiber S. Decreased interleukin-1 receptor antagonist response following moderate exercise in patients with colorectal carcinoma after primary treatment. Cancer Detect Prev. 2004;28(3):208–13. doi:10.1016/j.cdp.2004.02.001.

Allgayer H, Owen RW, Nair J, Spiegelhalder B, Streit J, Reichel C, et al. Short-term moderate exercise programs reduce oxidative DNA damage as determined by high-performance liquid chromatography-electrospray ionization-mass spectrometry in patients with colorectal carcinoma following primary treatment. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2008;43(8):971–8. doi:10.1080/00365520701766111.

Lee DH, Kim JY, Lee MK, Lee C, Min JH, Jeong DH, et al. Effects of a 12-week home-based exercise program on the level of physical activity, insulin, and cytokines in colorectal cancer survivors: a pilot study. Support Care Cancer. 2013;21(9):2537–45. doi:10.1007/s00520-013-1822-7.

Strasser B, Steindorf K, Wiskemann J, Ulrich CM. Impact of resistance training in cancer survivors: a meta-analysis. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2013;45(11):2080–90. doi:10.1249/MSS.0b013e31829a3b63.

Buchheit M, Laursen PB. High-intensity interval training, solutions to the programming puzzle. Part I: cardiopulmonary emphasis. Sports Med (Auckland, NZ). 2013;43(5):313–38. doi:10.1007/s40279-013-0029-x.

Buchheit M, Laursen PB. High-intensity interval training, solutions to the programming puzzle. Part II: anaerobic energy, neuromuscular load and practical applications. Sports Med (Auckland, NZ). 2013;43(10):927–54. doi:10.1007/s40279-013-0066-5.

Laursen PB, Jenkins DG. The scientific basis for high-intensity interval training: optimising training programmes and maximising performance in highly trained endurance athletes. Sports Med (Auckland, NZ). 2002;32(1):53–73.

Laursen PB, Blanchard MA, Jenkins DG. Acute high-intensity interval training improves Tvent and peak power output in highly trained males. Can J Appl Physiol. 2002;27(4):336–48.

MacDougall JD, Hicks AL, MacDonald JR, McKelvie RS, Green HJ, Smith KM. Muscle performance and enzymatic adaptations to sprint interval training. J Appl Physiol (Bethesda, Md : 1985). 1998;84(6):2138–42.

Gibala MJ, Little JP, MacDonald MJ, Hawley JA. Physiological adaptations to low-volume, high-intensity interval training in health and disease. J Physiol. 2012;590(5):1077–84. doi:10.1113/jphysiol.2011.224725.

Little JP, Safdar A, Bishop D, Tarnopolsky MA, Gibala MJ. An acute bout of high-intensity interval training increases the nuclear abundance of PGC-1alpha and activates mitochondrial biogenesis in human skeletal muscle. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2011;300(6):R1303–10. doi:10.1152/ajpregu.00538.2010.

Gibala MJ, McGee SL, Garnham AP, Howlett KF, Snow RJ, Hargreaves M. Brief intense interval exercise activates AMPK and p38 MAPK signaling and increases the expression of PGC-1alpha in human skeletal muscle. J Appl Physiol (Bethesda, Md : 1985). 2009;106(3):929–34. doi:10.1152/japplphysiol.90880.2008.

Little JP, Safdar A, Wilkin GP, Tarnopolsky MA, Gibala MJ. A practical model of low-volume high-intensity interval training induces mitochondrial biogenesis in human skeletal muscle: potential mechanisms. J Physiol. 2010;588(6):1011–22. doi:10.1113/jphysiol.2009.181743.

Wisløff U, Støylen A, Loennechen JP, Bruvold M, Rognmo Ø, Haram PM, et al. Superior cardiovascular effect of aerobic interval training versus moderate continuous training in heart failure patients: a randomized study. Circulation. 2007;115(24):3086–94. doi:10.1161/circulationaha.106.675041.

Schoenfeld BJ. The mechanisms of muscle hypertrophy and their application to resistance training. J Strength Cond Res / Natl Strength Cond Assoc. 2010;24(10):2857–72. doi:10.1519/JSC.0b013e3181e840f3.

Schoenfeld BJ. Postexercise hypertrophic adaptations: a reexamination of the hormone hypothesis and its applicability to resistance training program design. J Strength Cond Res / Natl Strength Cond Assoc. 2013;27(6):1720–30. doi:10.1519/JSC.0b013e31828ddd53.

Boutcher SH. High-intensity intermittent exercise and fat loss. J Obes. 2011;2011:868305. doi:10.1155/2011/868305.

Jacobs RA, Fluck D, Bonne TC, Burgi S, Christensen PM, Toigo M, et al. Improvements in exercise performance with high-intensity interval training coincide with an increase in skeletal muscle mitochondrial content and function. J Appl Physiol (Bethesda, Md : 1985). 2013;115(6):785–93. doi:10.1152/japplphysiol.00445.2013.

Tjønna AE, Lee SJ, Rognmo Ø, Stølen T, Bye A, Haram PM, et al. Aerobic interval training versus continuous moderate exercise as a treatment for the metabolic syndrome: a pilot study. Circulation. 2008;118(4):346–54. doi:10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.108.772822.

Boyle T, Lynch BM, Courneya KS, Vallance JK. Agreement between accelerometer-assessed and self-reported physical activity and sedentary time in colon cancer survivors. Support Care Cancer : Off J Multinatl Assoc Support Care Cancer. 2015;23(4):1121–6. doi:10.1007/s00520-014-2453-3.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Funding

This study was funded by Queensland Health (Remserv) (project number 2013001802).

Jenkins D, Skinner T, Bolam K, Chambers S, Owens J and Gatford J. (2013–2014). What exercise is the most effective in improving the health of colorectal cancer survivors? Queensland Health (Remserv), AU$19,000

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Statement of human rights

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the Human Ethics Committee of the University of Queensland and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments.

Informed consent

Written and informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Devin, J.L., Sax, A.T., Hughes, G.I. et al. The influence of high-intensity compared with moderate-intensity exercise training on cardiorespiratory fitness and body composition in colorectal cancer survivors: a randomised controlled trial. J Cancer Surviv 10, 467–479 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11764-015-0490-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11764-015-0490-7