Abstract

Background

The Tobacco, Alcohol, Prescription Medication, and Other Substance use (TAPS) tool is a combined two-part screening and brief assessment developed for adult primary care patients. The tool’s first-stage screening component (TAPS-1) consists of four items asking about past 12-month use for four substance categories, with response options of never, less than monthly, monthly, weekly, and daily or almost daily.

Objective

To validate the TAPS-1 in primary care patients.

Design

Participants completed the TAPS tool in self- and interviewer-administered formats, in random order. In this secondary analysis, the TAPS-1 was evaluated against DSM-5 substance use disorder (SUD) criteria to determine optimal cut-points for identifying unhealthy substance use at three severity levels (problem use, mild SUD, and moderate-to-severe SUD).

Participants

Two thousand adult patients at five primary care sites.

Main Measures

DSM-5 SUD criteria were determined via the modified Composite International Diagnostic Interview. Oral fluid was used as a biomarker of recent drug use.

Key Results

Optimal frequency-of-use cut-points on the self-administered TAPS-1 for identifying SUDs were ≥ monthly use for tobacco and alcohol (sensitivity = 0.92 and 0.71, specificity = 0.80 and 0.85, AUC = 0.86 and 0.78, respectively) and any reported use for illicit drugs and prescription medication misuse (sensitivity = 0.93 and 0.89, specificity = 0.85 and 0.91, AUC = 0.89 and 0.90, respectively). The performance of the interviewer-administered format was similar. When administered first, the self-administered format yielded higher disclosure rates for past 12-month alcohol use, illicit drug use, and prescription medication misuse. Frequency of use alone did not provide sufficient information to discriminate between gradations of substance use problem severity. Among those who denied drug use on the TAPS-1, less than 4% had a drug-positive biomarker.

Conclusions

The TAPS-1 can identify unhealthy substance use in primary care patients with a high level of accuracy, and may have utility in primary care for rapid triage.

Similar content being viewed by others

INTRODUCTION

Tobacco,1 alcohol,2 illicit drugs,3 , 4 and non-medical prescription medication use5 contribute substantially to morbidity, mortality, and societal costs. Recent efforts have focused on identifying and addressing unhealthy substance use (the spectrum ranging from any drug use or alcohol consumption above guideline-recommended levels, through more severe substance use disorder [SUDs]) in primary care.6 , 7

There are many reasons for clinicians to identify unhealthy substance use in their patients, including formulating differential diagnoses of psychiatric and medical disorders that can be mimicked or worsened by substance use, informing preventive care, and avoiding potentially serious medication interactions.8 Screening for unhealthy substance use can initiate a broader conversation about behavioral health, and provides an opportunity to deliver prevention messages to those who screen negative. For those who screen positive, there is good evidence supporting the effectiveness of brief counseling for tobacco9 and alcohol.10 The evidence for illicit drugs is more equivocal, with some randomized studies showing promising results11 – 13 and others showing no effects in primary care patients.14 , 15

For patients with SUDs, interventions can be delivered in primary care or via referral to a specialist. There are Food and Drug Administration (FDA)-approved medications for treating SUDs for tobacco (nicotine replacement therapy, bupropion, varenicline), alcohol (acamprosate, disulfiram, naltrexone), and opioids (buprenorphine, methadone, naltrexone). Opioid overdose has reached epidemic levels in the United States,16 , 17 and primary care clinicians are uniquely suited to identify opioid risks and prevent overdose death. Many individuals may access primary care before they seek specialty addiction treatment. Thus, primary care offers an opportunity to identify opioid use disorders early in their progression, facilitate treatment, and reduce overdose risk (e.g., by providing education and naloxone to patients and their families).

Although there are a growing number of validated substance use screening tools, different tools have unique strengths and weaknesses. Many older substance use screening tools (e.g., the CAGE and AUDIT for alcohol) are limited by their focus on a single substance.18 Other validated tools, such as the World Health Organization (WHO) Alcohol, Smoking and Substance Involvement Screening Test (ASSIST),19 may be too lengthy, given the extreme time demands on primary care providers. Screening tools must be brief, while providing accurate detection. Research indicates that brief instruments can perform surprisingly well in detecting SUDs.8 , 15 , 20 – 22 Single-item screeners querying frequency of use in the past year can accurately identify patients with unhealthy drug8 and alcohol use22 and DSM-IV-defined alcohol or drug dependence.15 A recent study in US Veterans Affairs clinics found that a two-item screener had high sensitivity and specificity (0.92/0.93) for detecting SUD among a sample of veterans (95% male) in primary care.21 However, one limitation of these rapid screeners is that they do not differentiate between illicit drug and prescription medication misuse,8 , 15 , 21 a distinction that may be particularly important in primary care settings.

McNeely and colleagues20 recently reported a two-site validation study of the self-administered Substance Use Brief Screen (SUBS), which asks patients about use of tobacco, binge drinking (4 or more drinks in a day), illicit drug use, and prescription medication misuse. The SUBS was able to detect unhealthy use and SUDs for alcohol and any drugs (sensitivity/specificity for alcohol and any drug SUD = 0.94/0.65 and 0.86/0.82, respectively), but was less sensitive for prescription drug use disorders alone (sensitivity/specificity for SUD = 0.59/0.89).

The Tobacco, Alcohol, Prescription Medication, and Other Substance use (TAPS) tool is a two-step screening and brief assessment tool adapted from the NIDA Quick Screen24 and ASSIST-Lite25 (an abbreviated version of the WHO ASSIST).19 The TAPS tool consists of two parts: a rapid screener (TAPS-1) and a brief assessment (TAPS-2) for those who screen positive on TAPS-1 (e.g., analogous to using the PHQ-2 followed by PHQ-9 for depression screening).23 The TAPS tool, using this two-part approach, was recently validated in primary care by the National Drug Abuse Treatment Clinical Trials Network (NIDA CTN0059).26 The purpose of the present study was to examine the ability of the TAPS-1, as a standalone screener, to identify adult primary care patients with unhealthy substance use.

METHODS

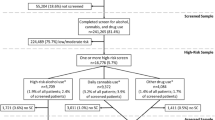

This secondary analysis examined the performance of the TAPS-1 in a geographically diverse sample of 2000 adult primary care patients. Methodological details of the parent study have been reported elsewhere27 and are summarized below.

Design and Setting

Recruitment took place from August 2014 to April 2015 at five primary care clinics in four Eastern US cities: a Federally Qualified Health Center in Baltimore, MD [n = 589]; a public hospital-based clinic in New York, NY [n = 534]; a university-based health center in Richmond, VA [n = 211]; and two private practices in Kannapolis, NC [n = 287 and 379].

Research assistants consecutively approached patients in each clinic’s waiting area and invited them to participate in an anonymous screening for a health study. Patients who agreed met with the research assistant in a private office and completed the TAPS tool in two formats sequentially (self-administered on an iPad, and interviewer-administered), with administration order determined at random. After patients had completed both formats, a battery of reference measures assessing substance use and related problems was administered by the research assistant.

Participants were paid $20 for completing the assessment, after which they were asked to provide an oral fluid sample for a drug test. Participants were paid an additional $10 if they provided the sample. Participants were not told about the oral fluid collection until all self-reported assessments were completed. The study was approved by the institutional review boards (IRBs) of Friends Research Institute and participating academic institutions, with a waiver of written consent, because this would be the only identifiable link to the data. Participants were given an IRB-approved information sheet.

Participants

The study had the following inclusion criteria: 1) adult (age 18 or older) primary care patient, and 2) able to provide informed consent. Participants were excluded if they 1) could not comprehend spoken English, 2) could not operate an iPad due to physical limitations, or 3) had previously enrolled during an earlier visit. Participants were 43.7% male, with 11.7% Hispanic ethnicity. Racial identification was 33.4% white and 55.6% black/African American. The average age was 46.0 years (SD = 14.7). With respect to education, 19.2% had not completed high school, 28.9% had a high school diploma/GED, 21.3% had some college (no degree), 11.2% had an associate’s degree, 14.0% had a bachelor’s degree, and 5.5% had a graduate/professional degree.

Measures

TAPS-1

The TAPS-1 is the screening component of the TAPS tool, and consists of a single stem question with four items covering frequency of past-12-month use of tobacco, alcohol, and illicit drugs, and non-medical use of prescription medications (Fig. 1). In this study, the TAPS-1 was administered as part of the full TAPS tool26; the focus of the present analysis is exclusively on the TAPS-1.

SUD Criteria

Diagnostic criteria for SUDs were assessed using the modified World Mental Health Composite International Diagnostic Interview (WMH-CIDI)28 items mapping to the SUD criteria in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition (DSM-5).29 Consistent with DSM-5, our scoring dropped the DSM-IV criterion on legal problems and included the item on craving. DSM-5 criteria were assessed separately for tobacco, alcohol, marijuana, cocaine, methamphetamine, heroin, and non-medical use of prescription opioids, sedatives, and stimulants. Because the WMH-CIDI does not include many of the DSM-5 tobacco use disorder criteria, tobacco use disorder was assessed using the language from the WMH-CIDI drug section. To facilitate direct comparison with the categories queried by the TAPS-1, we calculated DSM-5 scores for (a) tobacco, (b) alcohol, (c) any illicit drugs, and (d) any prescription medications used non-medically. We examined unhealthy substance use at sub-diagnostic “problem use” (≥1 DSM-5 criteria), mild SUD (≥2 DSM-5 criteria) and moderate-to-severe SUD (≥4 DSM-5 criteria) thresholds.

Oral Fluid

Oral fluid cheek swab specimens were tested for recent drug use via enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) screening with liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS) confirmation for amphetamines; methamphetamine including ecstasy/MDMA/MDA/MDEA; cocaine/benzoylecgonine; cannabis (THC); opiates (morphine, heroin metabolite, codeine, hydrocodone); oxycodone; methadone; barbiturates; phencyclidine; and benzodiazepines. Oral fluid rather than urine specimens were collected because oral fluid could be more efficiently obtained and shipped, and has been found to have adequate reliability.30 The package insert noted good agreement with gas chromatography–mass spectrometry (GC-MS) results (e.g., benzodiazepines, 88%; opiates, 90%; cocaine, 93%; cannabis, 94%; methamphetamine, 98%). In this analysis, morphine with heroin metabolite was classified as illicit drug-positive; other opiates (including morphine alone) were classified as prescription medications. Methamphetamine/ecstasy/MDMA/MDA were classified as illicit drugs; amphetamines alone were classified as prescription medications. Research assistants collected information about prescription medications that participants reported taking medically as prescribed; oral fluid tests for those medications were not counted as positive. Of the 2000 participants, 1802 (90%) provided an oral fluid sample. Given a short detection window for oral fluid testing (several days), its comparison with self-reporting offers a conservative estimate of non-disclosure by permitting disconfirmation of self-reported abstinence on the TAPS-1.

DATA ANALYSIS

The TAPS-1 was compared against reference standards of problem use, mild SUD, and moderate-to-severe SUD for tobacco, alcohol, illicit drugs, and non-medical use of prescription medications, using receiver operating characteristic (ROC) analysis of the area under the curve (AUC), sensitivity, specificity, positive predictive value (PPV), and negative predictive value (NPV). Optimal cut-points were determined by maximizing sensitivity and specificity as measured by AUC and Youden’s J (sensitivity + specificity − 1), which combines sensitivity and specificity into a single performance index ranging from −1 to 1, with 1 indicating a “perfect” test.31 These measures of test performance were examined for both self- and interviewer-administered formats. We used χ2 tests of independence to compare disclosure rates (i.e., any self-reported past 12-month use) based on format administration order.

RESULTS

Substance Use Prevalence

Table 1 shows prevalence, based on responses to the modified CIDI, of problem use, mild SUD, and moderate-to-severe SUD. Overall prevalence of DSM-5 SUD (≥2 criteria) was 25% for tobacco, 14% for alcohol, 13% for illicit drugs, and 3.5% for prescription medications. Among those meeting SUD criteria for illicit drugs, 57% met criteria for cannabis, 42% for illicit stimulants (cocaine or methamphetamine), and 25% for heroin (some met criteria for multiple drug classes). Among those meeting SUD criteria for prescription medications, 69% met criteria for opioids, 40% for anxiety or sleep medications, and 11% for stimulants (some met criteria for multiple drug classes).

Performance of the TAPS-1

Table 2 shows the performance of the self-administered TAPS-1 for detecting unhealthy substance use at each severity threshold. For all four substance categories, the optimal cut-point on the TAPS-1 for detecting problem use was any use in the past 12 months (i.e., any response greater than ‘Never’). For detecting any SUD (including mild or moderate-severe SUD), optimal cut-points were monthly use for tobacco and alcohol, and any use for illicit drugs and prescription medications. These cut-points were also optimal for detecting moderate-to-severe SUD.

The analysis identified the same cut-points for the interviewer- and self-administered formats, with similar performance between the two formats (Online Appendix Table 1). However, participants disclosed substance use at higher rates on the self-administered format for all substances except tobacco. The greatest discrepancy was for prescription medication misuse, which was 50% higher on the self-administered than the interviewer-administered format (12% vs. 8%).

Administration Order Effects

For the interviewer-administered TAPS-1, there were no significant differences in past 12-month prevalence of tobacco, alcohol, illicit drug, or prescription medication misuse based on whether the test was delivered before or after the self-administered format (all ps > 0.05). Conversely, for the self-administered format, disclosure rates were significantly higher for every substance category except tobacco when the self-administered format preceded the interviewer-administered format. When the self-administered TAPS-1 was presented before vs. after the interviewer-administered TAPS-1, disclosure rates were higher for alcohol (48% vs. 37%; p <0 .001), illicit drugs (27% vs. 22%; p = .03), and prescription medications (16% vs. 8%; p < 0.001). On the self-administered TAPS-1, analyses stratified by administration order showed small differences in sensitivity/specificity for first vs. second administration for tobacco (0.93/0.81 vs. 0.90/0.79) alcohol (0.73/0.83 vs. 0.69/0.87), illicit drugs (0.91/0.84 vs. 0.95/0.87), and prescription medication misuse (0.86/0.87 vs. 0.93/0.94).

Disclosure Rates vs. Oral Fluid

Oral fluid testing provides a brief detection window of approximately 1–3 days since last drug use. For the interviewer-administered TAPS-1, 3.9% (54/1372) and 3.4% (57/1667) of participants who reported no illicit drug use or prescription medication misuse, respectively, had a positive oral fluid test. For the self-administered TAPS-1, 3.8% (51/1359) and 3.7% (58/1585) had a positive oral fluid test despite reporting no illicit drug use or prescription medication misuse, respectively. However, approximately 10% of the sample refused the oral fluid test, which could be for various reasons (e.g., lack of time, concerns about confidentiality, or lack of candor in self-report).

DISCUSSION

As a screening tool, the TAPS-1 is simple and brief. It asks four direct questions about past 12-month use for all major substance use categories: tobacco, alcohol, illicit drugs, and non-medical use of prescription medications. The TAPS-1 was able to accurately detect problem use and SUDs for broad categories of substance use, and can be used as a standalone tool for quick triage in primary care. When implemented as part of the full TAPS tool, the TAPS-1 branches directly to additional questions in the TAPS-2.26 Although adding the TAPS-2 questions does not appear to provide greater sensitivity for detecting unhealthy use of illicit or prescription substances as broad categories, the TAPS-2 questions fill in more granular details about specific substances used and related problems, which may be important for guiding clinical care.

Both self- and interviewer-administered formats were able to detect unhealthy substance use at various severity thresholds, with test performance falling in the acceptable to excellent range. A noteworthy difference between the two formats is that disclosure rates for prescription medication misuse were 50% higher with the self-administered format. However, this advantage in disclosure was seen only when this format was administered prior to the interviewer-administered TAPS-1, and this ordering had slightly lower sensitivity and specificity for illicit drugs and prescription medication misuse (perhaps because the reference standard itself was interviewer-administered). It is possible that participants were more reluctant to disclose substance use in a face-to-face interview than on a computer tablet,32 but that having the interviewer-administered questions first primed participants to subsequently reduce their level of candor. Another possibility is that interviewers clarified misunderstandings that could lead to false positives, and participants remembered these clarifications when taking the self-administered format. For the interviewer-administered TAPS, interviewers read the questions verbatim but were allowed to provide a brief clarification and explanation if requested. For both formats, participants responded under confidential research conditions, with the knowledge that the results would not enter their medical record. It is not known how patients’ willingness to disclose substance use might change under real-world practice conditions.

This study adds to a growing body of literature supporting the use of brief screening tools for identifying unhealthy substance use, and builds upon prior research demonstrating the validity of even single-item substance use questionnaires in primary care.8 , 15 , 20 , 22 What is unique to the TAPS-1 is that it screens for four substance categories, is validated for both interviewer- and self-administered formats, may be administered as a standalone screener or paired with a brief assessment (TAPS-2), and has high sensitivity and specificity for identifying unhealthy use of illicit drugs and prescription medications. This last feature is particularly important given the current opioid epidemic and high rates of overdose deaths related to prescription opioid use across the US.

This study demonstrated the validity of the TAPS-1 in both interviewer- and self-administered formats. Either format can be used in practice. An advantage of the self-administered version may be slightly higher disclosure of substance use (particularly prescription medication misuse), low staff burden, and the potential for seamless integration of screening results into the electronic medical record. Ultimately, the choice of which format to deploy will depend on workflow considerations that are to some extent unique to each primary care practice. However, given its brevity (typically <1 min), we recommend that the TAPS-1 be incorporated into routinized screening protocols whenever possible, with subsequent assessment and intervention by providers as needed.

As evidenced by different optimal cut-points, the TAPS-1 had some utility in discriminating between sub-diagnostic problem use and SUD for tobacco and alcohol, but the same cut-points optimally identified unhealthy use of illicit drugs and prescription medications at all severity thresholds examined. Hence, although the TAPS-1 is likely to be an excellent tool for initial triage in primary care, frequency of use alone does not provide sufficient information to accurately discriminate between gradations of severity. As with any brief screener, it is important to ask follow-up questions to better inform diagnoses and treatment plans. While some practices may choose to use the TAPS-1 as a standalone screening tool for initial triage, it is recommended that screening be followed by a more detailed assessment when unhealthy substance use is identified. For this reason, it was originally intended that a positive TAPS-1 screen would be followed by the corresponding TAPS-2 questions (which cover more recent use of specific substances and problems) to better inform clinical care for patients with unhealthy substance use.

Strengths of this study include the large sample, evaluation of both interviewer- and self-administered formats with randomized order, and inclusion of a drug use biomarker. This was a diverse sample with white, African American, and Hispanic participants recruited from five primary care sites across the Eastern United States. However, the extent to which findings may be generalized to other US regions or other countries is unknown. The TAPS-1 and reference standard measures were asked by the same interviewers. We determined unhealthy substance use via a structured interview with items mapping to DSM-5 criteria. This is the appropriate standard, but remains an imperfect way of capturing a complex and nuanced phenomenon. The TAPS-1 groups marijuana with illicit drugs; however, several states have decriminalized or even legalized recreational marijuana use. Finally, findings may not generalize to settings where disclosure of substance use carries potential consequences (e.g., criminal justice).

Disclosure of substance use at low levels can identify patients with problem use and SUDs with a high level of accuracy. No screening tool should be considered an end unto itself, but rather a means to triage patients and inform a more detailed clinical assessment. To that end, the TAPS-1 succeeds. The findings from the current study support the use of the TAPS-1 for rapid patient triage.

References

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Smoking-attributable mortality, years of potential life lost, and productivity losses—United States, 2000–2004. Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2008;57(45):1226–28.

Rehm J, Mathers C, Popova S, Thavorncharoensap M, Teerawattananon Y, Patra J. Global burden of disease and injury and economic cost attributable to alcohol use and alcohol-use disorders. Lancet. 2009;373:2223–33.

Degenhardt L, Whiteford HA, Ferrari AJ, et al. Global burden of disease attributable to illicit drug use and dependence: findings from the Global Burden of Disease Study 2010. Lancet. 2013;382:1564–74.

Degenhardt L, Hall W. Extent of illicit drug use and dependence, and their contribution to the global burden of disease. Lancet. 2012;379:55–70.

Birnbaum HG, White AG, Schiller M, Waldman T, Cleveland JM, Roland CL. Societal costs of prescription opioid abuse, dependence, and misuse in the United States. Pain Med. 2011;12:657–67.

McLellan AT, Woodworth AM. The Affordable Care Act and treatment for "substance use disorders:" implications of ending segregated behavioral healthcare. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2014;46:541–5.

Buck JA. The looming expansion and transformation of public substance abuse treatment under the Affordable Care Act. Health Aff. 2011;30:1402–10.

Smith PC, Schmidt SM, Allensworth-Davies D, Saitz R. A single-question screening test for drug use in primary care. Arch Intern Med. 2010;170:1155–60.

U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Final recommendation statement: tobacco smoking cessation in adults, including pregnant women: behavioral and pharmacotherapy interventions. 2015. Available at: http://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/page/document/recommendationstatementfinal/tobacco-use-in-adults-and-pregnant-women-counseling-and-interventions. Accessed 12 April 2017.

Moyer VA. Screening and behavioral counseling interventions in primary care to reduce alcohol misuse: U.S. preventive services task force recommendation statement. Ann Intern Med. 2013;159:210–8.

Bernstein J, Bernstein E, Tassiopoulos K, Heeren T, Levenson S, Hingson R. Brief motivational intervention at a clinic visit reduces cocaine and heroin use. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2005;77:49–59.

Humeniuk R, Ali R, Babor T, et al. A randomized controlled trial of a brief intervention for illicit drugs linked to the alcohol, smoking and substance involvement screening test (ASSIST) in clients recruited from primary health-care settings in four countries. Addiction. 2012;107:957–66.

Gelberg L, Andersen RM, Afifi AA, et al. Project QUIT (Quit Using Drugs Intervention Trial): a randomized controlled trial of a primary care-based multi-component brief intervention to reduce risky drug use. Addiction. 2015;110:1777–90.

Roy-Byrne P, Bumgardner K, Krupski A, et al. Brief intervention for problem drug use in safety-net primary care settings: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2014;312:492–501.

Saitz R, Cheng DM, Allensworth-Davies D, Winter MR, Smith PC. The ability of single screening questions for unhealthy alcohol and other drug use to identify substance dependence in primary care. J Stud Alcohol Drugs. 2014;75:153–7.

Dart RC, Severtson SG, Bucher-Bartelson B. Trends in opioid analgesic abuse and mortality in the United States. N Engl J Med. 2015;372:1573–4.

Rudd RA, Aleshire N, Zibbell JE, Gladden RM. Increases in drug and opioid overdose deaths—United States, 2000–2014. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2016;64:1378–82.

Pilowsky DJ, Wu LT. Screening for alcohol and drug use disorders among adults in primary care: a review. Subst Abuse Rehabil. 2012;3:25–34.

Humeniuk R, Ali R, Babor TF, et al. Validation of the alcohol, smoking and substance involvement screening test (ASSIST). Addiction. 2008;103:1039–47.

McNeely J, Cleland CM, Strauss SM, Palamar JJ, Rotrosen J, Saitz R. Validation of self-administered single-item screening questions (SISQs) for unhealthy alcohol and drug use in primary care patients. J Gen Intern Med. 2015;30:1757–64.

Tiet QQ, Leyva YE, Moos RH, Frayne SM, Osterberg L, Smith B. Screen of drug use: diagnostic accuracy of a new brief tool for primary care. JAMA Intern Med. 2015;175:1371–7.

Smith PC, Schmidt SM, Allensworth-Davies D, Saitz R. Primary care validation of a single-question alcohol screening test. J Gen Intern Med. 2009;24:783–8.

Arroll B, Goodyear-Smith F, Crengle S, et al. Validation of PHQ-2 and PHQ-9 to screen for major depression in the primary care population. Ann Fam Med. 2010;8:348–53.

National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA). Resource guide: screening for drug use in general medical settings. 2016. Available at: https://www.drugabuse.gov/publications/resource-guide-screening-drug-use-in-general-medical-settings/nida-quick-screen. Accessed 12 April 2017.

Ali R, Meena S, Eastwood B, Richards I, Marsden J. Ultra-rapid screening for substance-use disorders: the Alcohol, Smoking and Substance Involvement Screening Test (ASSIST-Lite). Drug Alcohol Depend. 2013;132:352–61.

McNeely J, Wu LT, Subramaniam G, et al. Performance of the tobacco, alcohol, prescription medication, and other substance use (TAPS) tool for substance use screening in primary care patients. Ann Intern Med. 2016;165(10):690–699.

Wu LT, McNeely J, Subramaniam GA, Sharma G, VanVeldhuisen P, Schwartz RP. Design of the NIDA clinical trials network validation study of tobacco, alcohol, prescription medications, and substance use/misuse (TAPS) tool. Contemp Clin Trials. 2016;50:90–97.

World Health Organization. The World Mental Health Composite International Diagnostic Interview. 2015. Available at: http://www.hcp.med.harvard.edu/wmhcidi/index.php. Accessed 12 April 2017.

American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5). 2013. Available at: https://www.psychiatry.org/psychiatrists/practice/dsm/dsm-5. Accessed 12 April 2017.

Bosker WM, Huestis MA. Oral fluid testing for drugs of abuse. Clin Chem. 2009;55(11):1910–1931.

Perkins NJ, Schisterman EF. The inconsistency of "optimal" cutpoints obtained using two criteria based on the receiver operating characteristic curve. Am J Epidemiol. 2006;163:670–5.

Butler SF, Villapiano A, Malinow A. The effect of computer-mediated administration on self-disclosure of problems on the addiction severity index. J Addict Med. 2009;3:194–203.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

GA Subramaniam is an employee of the Center for Clinical Trials Network (CCTN), National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA), which is the funding agency for the National Drug Abuse Treatment Clinical Trials Network; her participation in this publication arises from her role as a project scientist under a cooperative agreement for this study. All other authors declare that they do not have a conflict of interest.

Funding Source

This study was supported by National Institute on Drug Abuse cooperative agreements: 5 U01 DA 013034; U10DA013727 and UG1DA040317; 3UG1DA013035. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institute on Drug Abuse or the National Institutes of Health.

Additional information

Clinical Trial Registration

ClinicalTrials.gov identifier NCT02110693.

Electronic supplementary material

Online Appendix Table 1

(DOCX 13 kb)

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Gryczynski, J., McNeely, J., Wu, LT. et al. Validation of the TAPS-1: A Four-Item Screening Tool to Identify Unhealthy Substance Use in Primary Care. J GEN INTERN MED 32, 990–996 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-017-4079-x

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-017-4079-x