Abstract

There is growing evidence on the effect of face mask use in controlling the spread of COVID-19. However, few studies have examined the effect of local face mask policies on the pandemic. In this study, we developed a dynamic compartmental model of COVID-19 transmission in New York City (NYC), which was the epicenter of the COVID-19 pandemic in the USA. We used data on daily and cumulative COVID-19 infections and deaths from the NYC Department of Health and Mental Hygiene to calibrate and validate our model. We then used the model to assess the effect of the executive order on face mask use on infections and deaths due to COVID-19 in NYC. Our results showed that the executive order on face mask use was estimated to avert 99,517 (95% CIs 72,723–126,312) COVID-19 infections and 7978 (5692–10,265) deaths in NYC. If the executive order was implemented 1 week earlier (on April 10), the averted infections and deaths would be 111,475 (81,593–141,356) and 9017 (6446–11,589), respectively. If the executive order was implemented 2 weeks earlier (on April 3 when the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention recommended face mask use), the averted infections and deaths would be 128,598 (94,373–162,824) and 10,515 (7540–13,489), respectively. Our study provides public health practitioners and policymakers with evidence on the importance of implementing face mask policies in local areas as early as possible to control the spread of COVID-19 and reduce mortality.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The 2019 novel coronavirus (SARS-CoV-2, which causes the disease COVID-19) has been spreading at an alarming rate in the USA and globally [1, 2]. In the USA, New York City (NYC) was the epicenter of the pandemic and has the highest mortality rate among all the major cities. As of August 25, 2020, more than 230,000 cases of COVID-19 have been confirmed in NYC, resulting in over 23,000 deaths [3]. As the largest and most densely populated city in the USA, NYC faces incomparable challenges in the social distancing needed to contain the spread of the virus [4, 5].

On April 3, 2020, the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) recommended “wearing cloth face coverings in public settings where other social distancing measures are difficult to maintain (e.g., grocery stores and pharmacies) especially in areas of significant community-based transmission” [6]. Although face mask use by the general public has been recommended in many countries to reduce COVID-19 transmissions [7,8,9,10] it was for the first time being recommended in the USA. There is growing evidence that face masks can protect the wearer from being infected by respiratory diseases or infecting others [11,11,13]. On April 17, 2020, an executive order was implemented that requires all residents over the age of 2 years in New York to wear masks or face coverings when they are in public and social distancing is impossible [14]. However, it is unclear how this executive order would affect the spread of COVID-19 in NYC.

This study aims to use a dynamic compartmental model to estimate the effect of the executive order on face mask use on COVID-19 infections and deaths. We used COVID-19 data in NYC and the best available evidence to inform model parameters. We estimated the averted numbers of infections and deaths due to the executive order on face mask use. We also studied what would happen if the executive order was implemented earlier. Findings from this study will provide policymakers with important information on the effect of face mask related policies in NYC and other parts of the USA.

Methods

Data Sources

We obtained the NYC COVID-19 data from the NYC Department of Health and Mental Hygiene (DOHMH) [3]. Our data included the number of daily and cumulative confirmed cases and deaths from February 29 to June 7, 2020 (Table S1). We intentionally chose the last day of evaluation to be June 7, a day before NYC initiated its first phase of reopening, as social distancing is likely to change after June 7. We estimated the disease progression and individual behavioral parameters from the literature (Table S2).

Model Formulation and Assumptions

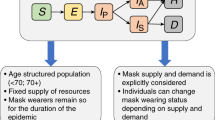

We developed a dynamic compartmental model to describe the transmission of COVID-19 in NYC. The model was based on a model framework we have recently published [15,16,17,18,19]. Figure 1 shows the structure of our model. Specifically, the NYC population was divided into nine compartments, including susceptible individuals (S), latent individuals (E), asymptomatic infections (A, infected individuals without symptoms), undiagnosed infections with mild/moderate (I1) and severe/critical symptoms (I2), diagnosed infections with mild/moderate (T1) or severe/critical symptoms (T2), recovered (R), and deceased (D) cases. Susceptible individuals could be infected by contacts with latent, asymptomatic, and undiagnosed infections with mild/moderate and severe/critical symptoms in public settings (e.g., public transportation, supermarkets, and offices) and households (home or other private settings) with a probability Λ (the force of infection) (a detailed description of Λ was provided in the Supplementary Appendix).

Flow chart of COVID-19 transmission model in New York City. The total population is divided into nine compartments: susceptible individuals (S), latent individuals (E), asymptomatic infections (A), undiagnosed infections with mild/moderate (I1) and severe/critical symptoms (I2), diagnosed infections with mild/moderate (T1) and severe/critical symptoms (T2), recovered (R), and deceased (D) cases. The force of infection is denoted as Λ, which involves two transmission patterns: public settings (e.g., public transportation, supermarkets, and offices) and households. The model includes three control measures: handwashing, social distancing, and face mask use. More details on Λ are provided in the Supplementary Appendix. The average incubation period is 1/k1, and the probability that an individual is asymptomatic is ρ. Infectious individuals with mild/moderate and severe/critical symptoms are diagnosed and treated at the rates of α1 and α2, respectively. We assume that these diagnosed individuals are isolated strictly and could not further infect others. Undiagnosed and diagnosed mild/moderate cases progress to the severe/critical stage at the rates of k2 and k3, respectively. Asymptomatic infections and undiagnosed mild/moderate cases are assumed to recover naturally at the rate of γ0. Diagnosed mild/moderate and severe/critical cases will recover at the rates of γ1 and γ2, respectively. Undiagnosed and diagnosed severe/critical cases will die due to the disease at the rates of μ1 and μ2, respectively

Latent individuals’ progress to the infectious compartment with mild/moderate symptoms or asymptomatic compartment at a rate of k1, and the probability that an individual is asymptomatic is ρ. Infectious individuals with mild/moderate and severe/critical symptoms are diagnosed and treated at the rates α1 and α2, respectively. We assumed these diagnosed individuals were isolated strictly and could not further infect others. Undiagnosed and diagnosed mild/moderate cases progress to the severe/critical stage at the rates of k2 and k3, respectively. Asymptomatic infections and undiagnosed mild/moderate cases are assumed to recover naturally at the rate of γ0. Diagnosed mild/moderate and severe/critical cases will recover at the rates of γ1 and γ2, respectively. Undiagnosed and diagnosed severe/critical cases will die due to the disease at the rates of μ1 and μ2, respectively.

The CDC recommended face mask use by the general public on April 3, 2 weeks before the executive order on face mask use was implemented on April 17 in New York [14]. In the baseline analysis, we assumed that the proportion of face mask use by the general public increased from 0% on April 3 to 100% on April 17 when the executive order was implemented. While the executive order has been enforced to some degree, it is possible that some people may not follow the order. Thus, we varied the proportion of face mask use in the sensitivity analysis to examine the robustness of our results with regards to this parameter. We also assumed that the baseline effectiveness of face mask in preventing COVID-19 infection or infecting others is 85% (95% CI, 66–93%) based on a recent meta-analysis on the effectiveness of face masks for COVID-19 [13]. Since there are a variety of face masks (from cloth masks to surgical masks), which may increase the uncertainty in face mask effectiveness, we varied the face mask effectiveness from 0 to 100% in our sensitivity analysis (Fig. 3).

Model Calibration

We calibrated the model using data on daily and cumulative confirmed infections and deaths and estimated parameters using a nonlinear least-squares method. The unknown parameters (Table S2) were sampled within their ranges by the Latin hypercube sampling method and repeated 1000 times. For every simulation, we calculated the sum of square errors between the model output and data and selected the top 10% with the least square errors to generate 95% confidence intervals. The detailed calibration procedure is provided in the Supplementary Appendix. All analyses and simulations were performed in MATLAB R 2019b.

Construction of Scenarios

We constructed four scenarios: (1) the status quo for which the executive order on face mask use was implemented on April 17 (baseline scenario) and three hypothetical scenarios, including (2) no face mask use; (3) the executive Order was implemented 1 week earlier on April 10; and (4) the executive order was implemented 2 weeks earlier on April 3, the same day the CDC started recommending face mask use by the general public. We considered the two hypothetical scenarios in which the executive order was implemented 1 and 2 weeks earlier because we assumed that the initiation time of the face mask executive order by a state government should not be earlier than the release of the CDC’s recommendation on face mask use. We simulated the epidemic trend of infections and deaths in the above four scenarios and plotted them for scenarios (1) and (2) in Fig. 2. We also calculated the number of averted infections and deaths from February 29 to June 7 for scenarios (1), (3). and (4), compared with scenario (2).

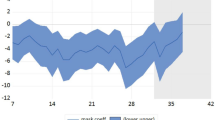

Model calibration based on reported confirmed COVID-19 (a) cases and (b) deaths in New York City. Two scenarios are plotted: (1) the status quo (blue lines) of executive order on face mask use implemented on April 17 after April 3 when the CDC began to recommend face mask use (baseline scenario) and (2) the hypothetical scenario without face mask use (solid black lines)

Sensitivity Analysis

We performed sensitivity analyses on the effectiveness of face masks and proportion of face mask use and estimated how they would affect the number of averted infections and deaths.

Results

Under the status quo, the estimated number of COVID-19 infections and deaths from February 29 to June 7 were 195,617 (95% CIs 151,580–239,653) and 17,322 (13,144–21,501), which were well consistent with reported data, as shown in Fig. 2. In the absence of face mask use, the estimated number of infections and deaths would be 295,134 (224,459–365,809) and 25,301 (18,845–31,756), respectively (Table 1), indicating 99,517 (72,723–126,312) infections and 7,978 (5,692–10,265) deaths would have been averted through face mask use.

If the executive order was implemented 1 week earlier on April 10, the estimated number of infections and deaths were 183,659 (142,710–224,608) and 16,284 (12,389–20,178), respectively (Table 1), suggesting that 111,475 (81,593–141,356) infections and 9017 (6446–11,589) deaths would be averted compared with no face mask use. If the executive order was implemented 2 weeks earlier on April 3, the same day as the CDC started recommending face mask use, 128,598 (94,373–162,824) infections and 10,515 (7540–13,489) deaths would have been averted.

The sensitivity analysis (Fig. 3) showed that when applied to the status quo, if the effectiveness of a face mask is 50%, the executive order would have averted 73,757 (53,663–93,850) infections and 5852 (4157–7547) deaths. Even if the effectiveness of face mask was as low as 20%, the executive order would still avert 37,206 (26,944–47,468) infections and 2916 (2062–3771) deaths. If the effectiveness of a face mask is 50% but the proportion of face mask use decreased to 75%, the executive order would have averted 60,678 (44,071–77,285) infections and 4792 (3398–6186) deaths. If the proportion of face mask use further decreased to 50%, the executive order would have averted 44,632 (32,346–56,917) infections and 3506 (2481–4531) deaths. This suggests that even with reduced effectiveness and use rate, the executive order on face mask use would prevent a large number of COVID-19 infections and deaths.

Discussion

This study assessed the effect of an executive order on face mask use on the spread of COVID-19 in NYC. We estimated that the executive order implemented on April 17 would avert approximately 100,000 infections and 8000 deaths in NYC, compared with no face mask use. Findings from our study are consistent with those reported in another recent study that modeled the impact of face mask use [20]. If the executive order was implemented a week earlier, it would avert 10,000 additional infections and 1000 additional deaths. This powerful effect would come at a minimal financial cost, particularly compared with some contact reduction measures such as closing restaurants or other social venues.

Our findings suggest that increasing face mask use would significantly reduce the spread of COVID-19 in NYC. This finding is consistent with a recent study in Wuhan, China, which demonstrated that high face mask use was necessary to prevent a second major outbreak in the city after the lifting of the metropolitan-wide quarantine [21]. Face mask use by the general public is further supported by similar practices in Singapore and Hong Kong where the governments have required their residents to wear masks in public settings and the changing position of the World Health Organization and the CDC to recommend mass population use of face masks [7, 9, 22,23,24,25]. More importantly, a large proportion of transmission may occur from individuals infected by COVID-19 but showing no specific signs of symptoms, and face mask use by the general public may prevent these asymptomatic individuals from spreading the virus [26]. Ensuring face mask use by the general public is necessary to maximize the chances of curbing the pandemic and reducing the number of COVID-19-related hospitalizations and deaths.

Widespread face mask use by the general public faces a number of challenges. First, a change in perceptions related to face mask use requires time and effort. An online survey conducted in May, 2020, showed that about 78% of survey participants wore a face mask in public and participants in those states with an executive order on face mask use were more likely to wear face masks [27]. This is a substantial improvement from the previous unwillingness and ambivalence of using a face mask, but the usage level is still lower than other countries such as South Korea (89%) [28]. Second, there is a face mask shortage in NYC and across the USA in general, which has led to the prioritization of face masks for healthcare workers and those in direct contact with infected individuals. To cope with the shortage, the CDC has recommended the use of homemade cloth face coverings in public settings and areas of significant community-based transmission [6]. Although homemade face coverings may not be as effective as face masks, it will likely still have some effectiveness in transmission prevention. Our sensitivity analysis showed that even with a 20% efficacy, the executive order on face mask use would still avert about 37,000 infections and 3000 deaths in NYC.

Our study has several limitations and practical simplifying assumptions. First, we assumed a homogenous use of face masks among the general population. In reality, people with symptoms are more likely to wear a face mask, whereas people with no symptoms are less likely to wear a face mask. Second, the model did not identify people who are specifically at high risk, such as people living in a population-dense area and people who are in close contact with infected individuals. Third, we did not model COVID-19 infections and deaths across different racial/ethnic groups due to the lack of such granular data over the study period. Lastly, the effectiveness of face mask varies considerably across different types of masks. To account for parameter uncertainty, we estimated the effectiveness of face mask based on a most recent meta-analysis and performed sensitivity analyses on the key model parameters [13].

Conclusions

Our study indicates that the executive order on face mask use may play an important role in mitigating the burden of COVID-19 in NYC. The earlier the executive order was implemented, the more infections and deaths would be averted. This will help policymakers make more informed decisions on whether and when policies on face mask use should be implemented across the country.

Data Availability

The COVID-19 data used in this modeling study can be found in the Supplementary Document and the NYC Department of Health and Mental Hygiene website: https://www1.nyc.gov/site/doh/covid/covid-19-main.

References

Omer SB, Malani P, del Rio C. The COVID-19 pandemic in the US: a clinical update. JAMA. 2020;323(18):1767–68.

Sohrabi C, Alsafi Z, O’Neill N, et al. World Health Organization declares global emergency: a review of the 2019 novel coronavirus (COVID-19). Int J Surg. 2020;76:71–6.

New York City Department of Health and Mental Hygiene. COVID-19: DATA. Accessed April 13, 2020. https://www1.nyc.gov/site/doh/covid/covid-19-data.page

Tanne JH. Covid-19: New York City deaths pass 1000 as Trump tells Americans to distance for 30 days. BMJ. 2020;369:m1333.

Wadhera RK, Wadhera P, Gaba P, et al. Variation in COVID-19 hospitalizations and deaths across New York City boroughs. JAMA. 2020;323(21):2192–95.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Considerations for Wearing Masks. Accessed April 16, 2020. https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/prevent-getting-sick/cloth-face-cover.html

Feng S, Shen C, Xia N, Song W, Fan M, Cowling BJ. Rational use of face masks in the COVID-19 pandemic. Lancet Respir Med. 2020;8(5):434–6.

Wang CJ, Ng CY, Brook RH. Response to COVID-19 in Taiwan: big data analytics, new technology, and proactive testing. JAMA. 2020;323(14):1341–2.

Cheng VC, Wong S-C, Chuang VW, et al. The role of community-wide wearing of face mask for control of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) epidemic due to SARS-CoV-2. J Infect. 2020;81(1):107–14.

Zhang L, Tao Y, Shen M, Fairley CK, Guo Y. Can self-imposed prevention measures mitigate the COVID-19 epidemic? PLOS' Medicine. 17(7):e1003240.

MacIntyre CR, Cauchemez S, Dwyer DE, et al. Face mask use and control of respiratory virus transmission in households. Emerg Infect Dis. 2009;15(2):233–41.

Lai ACK, Poon CKM, Cheung ACT. Effectiveness of facemasks to reduce exposure hazards for airborne infections among general populations. J R Soc Interface. 2012;9(70):938–48.

Chu DK, Akl EA, Duda S, et al. Physical distancing, face masks, and eye protection to prevent person-to-person transmission of SARS-CoV-2 and COVID-19: a systematic review and meta-analysis. The Lancet. 2020;395(10242):1973–87.

New York State Department. No. 202.79: Continuing temporary suspension and modification of laws relating to the disaster emergency. 2020. https://www.governor.ny.gov/news/no-20279-continuing-temporary-suspension-and-modification-laws-relating-disaster-emergency. Accessed 16 Apr 2020.

Shen M, Peng Z, Xiao Y, Zhang L. Modeling the Epidemic Trend of the 2019 Novel Coronavirus Outbreak in China. The Innovation. 2020;1(3).

Shen M, Peng Z, Guo Y, Rong L, Li Y, Xiao Y, Zhuang G, Zhang L, (2020) Assessing the effects of metropolitan-wide quarantine on the spread of COVID-19 in public space and households. International Journal of Infectious Diseases 96:503–505.

Bai L, Lu H, Hu H, et al. Evaluation of Work Resumption Strategies after COVID-19 Reopening in the Chinese City of Shenzhen: A Mathematical Modeling Study. Publ Health. 2020;(in press).

Zhang L, Tao Y, Wang J, Ong JJ, Tang W, Zou M, et al. Early characteristics of the COVID-19 outbreak predict the subsequent epidemic scope. International Journal of Infectious Diseases 2020;97:219–224.

Zhang L, Tao Y, Zhuang G, Fairley CK. Characteristics Analysis and Implications on the COVID-19 Reopening of Victoria, Australia. The Innovation 2020;1(3):100049.

Ngonghala CN, Iboi E, Eikenberry S, et al. Mathematical assessment of the impact of non-pharmaceutical interventions on curtailing the 2019 novel Coronavirus. Math Biosci. 2020;325:108364.

Zhang L, Shen M, Ma X, et al. What is required to prevent a second major outbreak of the novel coronavirus COVID-19 upon lifting quarantine in Wuhan City, China. The Innovation. 2020;1(1):100006.

Greenhalgh T, Schmid MB, Czypionka T, Bassler D, Gruer L. Face masks for the public during the covid-19 crisis. BMJ. 2020;369:m1435.

Tan A. COVID-19: Reusable masks will be given out to S’pore residents from 5 to 12 April. MSN. 2020. https://www.msn.com/en-sg/news/singapore/covid-19-reusable-masks-will-be-given-out-to-spore-residents-from-5-to-12-april/ar-BB127rN0

Lyu W, Wehby GL. Community use of face masks and COVID-19: evidence from a natural experiment of state mandates in the US: study examines impact on COVID-19 growth rates associated with state government mandates requiring face mask use in public. Health Aff (Millwood). 2020;39(8):1419–25.

Hartley DM, Perencevich EN. Public health interventions for COVID-19: emerging evidence and implications for an evolving public health crisis. Jama. 2020;323(19):1908–9.

Bai Y, Yao L, Wei T, Tian F, Jin DY, Chen L, et al. Presumed asymptomatic carrier transmission of COVID-19. Jama. 2020;323(14):1406–7.

Huprikar S, Ludolph T. Are americans wearing face masks. PREMISE. 2020. https://www.premise.com/are-americans-wearing-face-masks/. Accessed 16 Apr 2020.

So W. Comparison of face mask use before and after the COVID-19 outbreak in South Korea. Statista. 2020. https://www.statista.com/statistics/1103501/south-korea-mask-use-before-after-covid-19

Funding

This work was supported, in part, by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (81950410639 (L. Zhang), 11801435 (M. Shen), 11631012 (Y. Xiao), 11971375 (J. Zu)); Outstanding Young Scholars Support Program (3111500001 (L. Zhang)); Xi’an Jiaotong University Basic Research and Profession Grant (xtr022019003 (L. Zhang), xzy032020032 (L. Zhang)) and Xi’an Jiaotong University Young Scholar Support Grant (YX6J004 (L. Zhang)); Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation (20200344 (L. Zhang)); China Postdoctoral Science Foundation (2018M631134, 2020T130095ZX); the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities (xjh012019055, xzy032020026, xzy032020027); Natural Science Basic Research Program of Shaanxi Province (2019JQ-187, 2019JM-273); Xi’an Special Science and Technology Projects on Prevention and Treatment of Novel Coronavirus Penumonia Emergency (20200005YX005); Science Foundation for COVID-19 of Xi’an Jiaotong University Health Science Center and Qinnong Bank (2008124); Zhejiang University special scientific research fund for COVID-19 prevention and control (2020XGZX056). Y. Guo was supported by Career Development Fellowships of the Australian National Health and Medical Research Council (numbers APP1107107 and APP1163693). L. Rong was supported by National Science Foundation (DMS-1950254). A. Zebrowski and B.G. Carr was supported by the National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute of the National Institutes of Health (R01HL141841-01). Y. Li was supported by the National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute of the National Institutes of Health (R01HL141427). The contents of this paper are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of the funding institutions.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Y.L. and L.Z. conceived and designed the study. M.S. and J.Z. analyzed the data. M.S. and J.Z. carried out the analysis and performed numerical simulations. C.F., J.A.P., B.F., B.L., S.S.Y., E.C., G.L., Y.G., L.R., Y.X., G.Z. A.Z., and B.C. contributed to the validation and interpretation of the results. All the authors contributed to the writing the paper and critical revision of the first draft and approved the final manuscript for submission.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Ethics Approval and Consent to Participate

This study used only publicly available secondary data so ethics approval is not required.

Consent for Publication

Not applicable.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

ESM 1

(DOCX 302 kb)

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Shen, M., Zu, J., Fairley, C.K. et al. Effects of New York’s Executive Order on Face Mask Use on COVID-19 Infections and Mortality: A Modeling Study. J Urban Health 98, 197–204 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11524-021-00517-2

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11524-021-00517-2