Abstract

Objectives

If offending were simply displaced following (often spatially) focused crime reduction initiatives, the continued expenditure of resources on this approach to crime reduction would be pointless. The aims of this article were to: critically appraise the current body of displacement research; identify gaps in understanding; articulate an agenda for future research; and to consider the implications of the accumulated findings for practitioners, evaluators, and policy makers.

Methods

First, we review existing criminological theory regarding crime displacement and the alternative perspective—that crime prevention activity might generate a diffusion of crime control benefits. Second, we review the empirical research, focusing in particular on the findings of existing systematic reviews. Third, we consider the types of displacement that might occur and the methodological approaches employed to study them.

Results

Theoretical and empirical research suggests that displacement is far from inevitable and that a diffusion of crime control benefit is at least as likely. However, some forms of displacement have not been adequately studied.

Conclusion

Existing research suggests that successful crime reduction interventions often have a positive impact on crime that extends beyond the direct recipients of a particular project. However, current understanding of crime displacement and how benefits might diffuse remains incomplete. Consequently, to inform an agenda for future research, we derive a typology of methodological issues associated with studying displacement, along with suggestions as to how they might be addressed.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Support for the notion that crime will simply relocate in the aftermath of situational focused crime prevention initiatives is collectively absent in the research literature. On the contrary, over 30 years of research evidence on this topic, referred to as crime displacement, suggests that crime relocates in only a minority of instances. More commonly, it has been found that the opposite, a diffusion of crime reduction benefits in nearby areas not targeted by interventions, occurs at a rate that is about equal to observations of displacement (Guerette and Bowers 2009). The tendency of crime to behave in this way has now been repeatedly observed in an assortment of studies which include a controlled trial for which the study of displacement was the focus of the study (Weisburd et al. 2006) and a series of systematic and meta-analytic reviews of studies for which displacement was examined as a possible side effect of intervention (Guerette and Bowers 2009; Braga, et al. 2012; Telep et al. 2014), including a recent National Police Improvement Agency (NPIA)-funded systematic review (Bowers et al. 2010 2011) of the extent to which geographically focused police initiatives displace crime.

Despite this clear and repetitive finding, there remain limitations in how the existing research informs understanding of the potential varieties of crime displacement. Indeed, most evaluations of crime prevention efforts conducted historically were not cognizant of the issue of displacement (or that the reverse was possible) nor were they designed to detect such side effects. We know the most about geographic displacement, but other forms of displacement (and diffusion) are comparatively less studied and understood. The majority of the research on geographical crime displacement research has focused on proximal displacement patterns and, accordingly, we know much less about intermediate or distal crime movement. We have very few ethnographic studies of how offender behavior might change following the implementation of crime reduction interventions, and we continue to be limited by the short follow-up time periods typically used in evaluations of crime prevention initiatives.

So what does this mean for those who are concerned with crime reduction, if the scientific understanding of displacement remains incomplete? These limitations should promote caution, but they should not be used as justification for doing nothing about crime. Instead, the accumulated research evidence on displacement should be used to help refine thinking about the nature of offending, serve to illuminate remaining frontiers of crime (dis)placement research, help make research designs suitable for detecting displacement integral to future evaluations of crime prevention efforts, equip policymakers with an evidence-based understanding of crime patterns, and guide practitioners in the administration of informed and effective crime prevention initiatives.

The aim of this article is to lay the foundations for this thinking through an appraisal of the current body of research on crime displacement and a discussion of its implications for the future. What follows is informed by our analysis of a set of studies identified as part of a NPIA-funded Campbell collaboration review of the extent to which geographically focused police interventions displace crime (Bowers et al. 2011), and our systematic reviews of the extent to which situational crime prevention interventions displace crime (Guerette and Bowers 2009; Johnson et al. 2012).

The paper is organized in four parts. In the first, we discuss the theoretical basis for expecting crime displacement in its various forms and why it is equally logical to expect the reverse—a diffusion of crime control benefits (see Clarke and Weisburd 1994). In the second part, we review the evidence base in terms of the types of displacement considered and highlight gaps in knowledge. This is followed by the presentation of a typology of methodological issues associated with estimating the extent to which displacement may or may not occur and how these might be resolved. In the final section, we consider the implications of the accumulated findings for practitioners, evaluators, and policy makers.

The theoretical basis for (not) expecting crime displacement

Consciously or otherwise, offenders make a number of choices both when preparing for and when committing crime. The crime has to take place at a particular location, at a particular time, using specific tools (where appropriate), against a specific target, and with a desired outcome of a particular type. Independent of offender motivation, crime events can always be described in these terms. In some cases, an offender might choose to offend even if the presenting conditions make such action difficult or risky. However, our understanding of human nature suggests that typically the probability with which a crime will occur depends on the person–situation interaction. The offender as decision maker will weigh up whether a risk is worth taking or not. Such decision making may be heuristic in nature, and will likely be bounded insofar as the offender will not be in possession of complete and accurate information regarding any particular situation, and their decision making will be influenced by their experience and the outcome of previous choices made. These are the essential premises of the rational choice perspective (e.g., Cornish & Clarke 1987).

From this perspective, if offenders do evaluate (however briefly) the risks and rewards they perceive to be associated with a crime, it follows that, by manipulating these perceptions, crime can be made more or less likely to occur. This is the guiding principle of the situational approach to crime prevention (Clarke 1983). Hence, by hardening targets, reducing the rewards associated with criminal activity, by securing locations, removing or disallowing the tools for crime, or by discouraging unlawful behavior either provoked or permitted by a particular setting, crime may be prevented (so the theory goes).

But if such activity is successful, what happens in its wake? This is the question with which the displacement literature is concerned. Assuming that offender motivation remains unchanged by such action, it is plausible that, in being denied one opportunity, a motivated offender will simply target another. Alternative opportunities might be found in other geographical locations (spatial displacement), at other times (temporal displacement), or for other targets (target displacement). They may be made possible through the use of methods or tools not previously employed (tactical displacement), or an offender may focus on a different outcome, such as committing theft against the person rather than a burglary (crime type displacement). These five types of displacement were first defined by Hesseling (1994). Barr and Pease (1990) suggested a sixth, noting that, for example, the arrest of an offender might not lead to crime reduction if the opportunities for crime remain unaffected by intervention. For example, those offenders that are not arrested may easily exploit the opportunities that their incarcerated counterparts would otherwise have taken advantage of. Theoretically, this could occur, for example, in the event that a drug dealer is arrested, but the market for illegal drugs, and the opportunities to sell them, remain unaffected.

As noted, there has been considerable research investigating the extent to which displacement is likely to happen, both from a theoretical viewpoint and an empirical one. While theories of criminality (those that say there is a criminal ‘disposition’ for example) predict that displacement is an inevitable outcome of crime prevention (e.g., Yochelson and Samenow 1976).

Theoretically, it is often argued that it would be difficult to imagine that all crime reduction would lead to displacement. There will be situations where, by denying offenders an easy target, they merely give up on a finding a ‘replacement’, and there are many examples of where the evidence indicates that this is the case. To illustrate using a thought experiment, Nick Tilley asks whether crime would increase if all existing security measures were removed. The logical answer is yes, and the logical corollary is that by adding such measures the reverse must be true. The degree to which displacement is likely depends on a number of factors. This includes how invested an offender is in committing a crime, the degree to which the extra effort of finding and exploiting an alternative is worthwhile (it might not be for petty theft for example) and the degree to which offenders know of other potential situations that they can manipulate. To illustrate, in interviews with burglars, Bennett and Wright (1984) found that when prevented from committing an offence, less than half of the offenders (43 % in their sample) reported that they would seek out alternative opportunities. In fact, some reported that being thwarted in their efforts was perceived as signalling bad luck, which actively encouraged them to desist from engaging in crime at all that day.

A further explanation as to why offenders can be expected to desist from crime, rather than displace their activity, can be found in theories of routine activity (e.g. Cohen and Felson 1979) and offender mobility. Offenders are said to encode ‘mental maps’ of their environment (Brantingham and Brantingham 1981), which encapsulate their knowledge of the different spaces they encounter (mostly) during their routine activities. For example, they will likely be aware of the areas around their place of work, their home (‘nodes’), and other places they routinely frequent. Likewise, they will probably become familiar with the paths taken to travel between them. For such areas, they will develop an awareness of the area, including the crime opportunities—their associated risks (including the amount of guardianship) and potential rewards—to be found within them. However, not all offenders will be capable of exploiting all opportunities encountered. Some targets will be suitable for an offender, while others will not. If an offender is denied suitable opportunities to offend in those places of which they are aware, extra effort will be involved in seeking out new opportunities located elsewhere, some of which may be suitable, some of which may not. Not only will this require additional effort, which may be unproductive if suitable replacement targets are not identified, but offenders will experience greater uncertainty regarding the risks and rewards associated with newly identified targets. For this reason, Eck (1993) suggests the familiarity decay hypothesis, which states that the likelihood that an offender will target an opportunity will be inversely related to the distance it is located from their routine activity space(s). According to this theory, if an offender cannot find suitable targets near to known/preferred locations, displacement is less likely to occur.

An alternative perspective on crime displacement focuses on offender motivation and disposition. Through this lens, offenders (or at least some of them) will continue to offend independent of how difficult this might be, because they are pre-disposed to criminal activity. In this case, the only effective way of preventing crime is to address the so-called ‘root’ causes of it, which would involve not manipulating the immediate environment, but by changing, for example, the long-term socialisation and disposition of criminals so that they are no longer motivated to offend. Such thinking suggests a ‘hydraulic’ view of crime for which there will always be a certain amount of crime, the level of which will be a function of those dispositional factors that are hypothesized to influence offender motivation, factors that are independent of changes to the immediate situation.

This view predicts outcomes at one extreme of a continuum of possibilities that would follow the implementation of a successful intervention. However, research—such as that reported by Bennett and Wright (1984)—suggests that many offenders are not so disposed. Other possibilities are that there will be some displacement, but this will not be total displacement and therefore there will be some net benefit to intervention (Guerette and Bowers 2009). Barr and Pease (1990) consider a further perspective, differentiating between malign and benign displacement. The latter occurs where crimes prevented by an intervention are displaced but the overall outcome is more attractive than the alternative. Examples would include instances of crime switch where increases are observed in one type of crime that is perceived to be less serious than the type of crime prevented (e.g., offenders switch from burglary to shop theft). Malign displacement, on the other hand, would be said to have occurred if an intervention led to a change in crime patterns that are worse than before.

In contrast to the above thinking, Weisburd and Telp (2012) provide a contemporary view as to why crime should not displace at all. They do so by discussing the fact that empirical research on spatial patterns of crime suggests that crime is coupled to places. That is, while some places (where places may refer to units of analysis as discrete as street segments, or even smaller units of analysis such as intersections or individual addresses) experience little or no crime, others experience a disproportionate amount, and do so consistently over time. Leaving the precise theoretical explanation for this coupling aside for a moment, what such findings suggest is that the characteristics of places influence the level of crime at them. And, consequently, that if crime is prevented at particular locations, there is no reason to expect offenders to relocate their activity to other nearby locations unless those (alternative) locations share the same characteristics as the places where crime has been reduced. In this way, criminal activity may be resistant to displacement.

Considering why some places may experience much crime, Brantingham and Brantingham (1993) describe two types of crime hotspot: attractors and generators. The conceptual distinction between the two is that one attracts offenders to a particular area because the conditions there are perceived to be favorable for crime (e.g., locations with check cashing facilities), while the other generates crime (e.g., railway stations) because of the opportunities created by the volume of people (some of whom will be offenders) passing through them. Crime is expected to be high at crime generators as offenders simply take advantage of serendipitous opportunities encountered. Given the unplanned nature of such offending, there is no theoretical reason to expect crime to be displaced from such hotspots if interventions successfully suppress crime at those locations. In the case of crime attractors, if it is the specific characteristics of the location that attracts offenders to them, then theoretically there should be few (if any) other locations that are equally attractive to offenders. In which case, the removal of opportunities (perceived or otherwise) at such locations should not logically always lead to displacement.

In a landmark paper, Clarke and Weisburd (1994) presented a still further possibility—that interventions could actually reduce the risk of crime to targets not directly subject to intervention, such as those located nearby. They termed this possibility a diffusion of crime control benefit, though it is sometimes referred to as other things, such as the free rider effect. Clarke and Weisburd articulated two mechanisms through which such benefits might occur; discouragement and deterrence. Deterrence occurs when an offender is uncertain about the increased risk of offending (e.g.. overestimates the ‘reach’ of an intervention), whereas discouragement happens when changing target would involve extra effort or reduced reward (for recent advances, see Weisburd and Telp 2012).

From a theoretical viewpoint, it is also entirely feasible that interventions may simultaneously lead to both a diffusion of benefits and displacement. For example, as a result of a burglary reduction intervention, offenders might avoid an area of housing beyond that which actually received the intervention, but discover that vehicle crime in the same area represents a suitable alternative that they are capable of exploiting and target opportunities encountered. Such complexity means that it is not necessarily simple to measure the unintended consequences of intervention. However, this should not prevent attempts to do so. In the next section. we consider existing reviews on the topic, before discussing how future research might add to the evidence base.

Prior reviews of crime displacement

Various reviews have been conducted to investigate the degree to which displacement and diffusion occur. These have identified empirical evidence reported in primary evaluations and drawn conclusions using different techniques of evidence synthesis. The results of the early reviews, conducted in the 1990s (Barr and Pease 1990; Eck 1993; Hesseling 1994), suggested that displacement was far from inevitable and was often not apparent from the empirical data. The reviews also suggested that where displacement was detected it was not sufficient to rule out an overall positive effect of intervention. For example, in the study by Eck (1993), only 9 % of the 33 studies reviewed suggested a substantial amount of potential displacement. In 40 % of the cases reviewed by Hesseling (1994), no potential displacement was reported, and, for some of the studies, a potential diffusion of benefits was observed.

Criticisms of the earlier reviews are that they did not employ systematic search methods and hence their findings may be biased, and they typically employed a vote counting methodology of one form or another, simply counting, for example, the number of studies that showed significant positive or negative effects. As noted elsewhere (e.g., Petticrew 2006), one problem with the latter is that they do not formally take advantage of the cumulative body of evidence and typically rely on statistical significance as the threshold for counting votes, ignoring the size of the effects observed (and their variance). Consequently, such approaches can lead to errors of inference and a poor understanding of the size of effects observed. In contrast, meta-analytic techniques explicitly model effect sizes and their variance. This not only enhances understanding of the variation in effect sizes but increases statistical power, thereby reducing Type II statistical error (accepting the null hypothesis when it is in fact false).

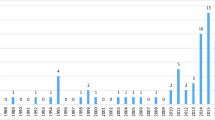

Several new reviews that employ systematic search criteria and meta-analytic (and other) techniques have been undertaken in the last few years, and these have concentrated on two broad types of intervention; situational crime prevention and geographically focused policing initiatives. Guerette and Bowers (2009) reported results from a systematic review of displacement and diffusion associated with situational interventions. In this case, findings from 102 primary evaluations were considered. A summary of the findings reported by the original study authors suggested that potential displacement was identified in 26 % of the cases where it was measured, and, interestingly, that a diffusion of benefit was found in a similar number of the tests (27 %). These findings were supported by a quantitative analysis conducted using data for the 13 studies for which relevant data were available. The measure of effect size used was the weighted displacement quotient (Bowers and Johnson 2003), which is a single metric that quantifies the size of changes observed in a nearby catchment area relative to those observed in the associated treatment area (and a suitable control area). This suggested that, when displacement did occur, it was only partial, and a diffusion of benefit was a slightly more likely outcome. An updated systematic review of displacement associated with SCP interventions was conducted by Johnson et al. (2012). In this study, the authors computed effect sizes similar to those used in a typical Campbell Collaboration review (see the discussion of odds ratios below), and very similar results emerged; that is, a diffusion of benefit was just as likely to be observed as spatial displacement.

Three further reviews have focused on displacement/diffusion associated with geographically focused policing initiatives. With NPIA funding, Bowers et al. (2011) undertook a systematic review for which this was the primary focus of the study, and examined the evidence associated with interventions such as directed patrol, police crackdown, problem-oriented policing, broken window approaches, civil remedies, and police-led environmental improvement. Where data permitted, they calculated (odds ratio) effect sizes for both the treatment site and surrounding catchment areas (data were available for 16 primary evaluations) into which crime would be most likely to displace geographically. One complication identified in this study was that, in some studies, more than one effect size could be computed for the same treatment or catchment area. For example, in some primary evaluations, changes were reported for more than one control area, or for a different period of time. Including all effect sizes in the analysis would violate the assumption of independence (a requirement of most statistical tests), and so a novel permutation approach was employed to estimate the overall mean effects of intervention. The overall results of their meta-analysis were consistent with those for situational crime prevention interventions; as a group, geographically focused policing interventions appear to be generally effective at reducing crime and a diffusion of crime control benefit appears to be at least as likely as displacement. Interestingly, a moderator analysis suggested that a diffusion of benefit was most likely where problem-oriented policing initiatives were implemented, where crime was reduced in the treatment areas (which might be interpreted as an indicator of implementation success), or where interventions were evaluated using designs that reduced the most threats to internal validity (randomized control designs).

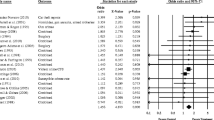

In their study, Braga et al. (2012) undertook an up-to-date review of police-led efforts to control crime in hotspots. In this case, the primary focus of the review was the direct impact on crime (i.e. the focus was not on crime displacement) of interventions such as directed patrol, heightened traffic enforcement, aggressive disorder enforcement, and problem-oriented policing. However, analyses were also presented regarding the extent to which such interventions were associated with crime displacement or a diffusion of crime control benefit. In addition to an overall significant crime-reductive effect of intervention, the meta-analysis suggested a small but significant diffusion of benefit for the 13 studies for which data were available. As found in the Bowers et al. study, successful crime reduction and a diffusion of crime control benefits appeared to be particularly characteristic of POP schemes (see Table 1). In the most recent review (also reported in this issue of the journal), Telep et al. (2014) examined the extent to which crime is displaced, or benefits diffused, for geographically focused police interventions that are implemented in medium-large sized areas. Their findings are consistent with those shown in Table 1.

Present methodological limitations

Quantifying effects

As discussed, spatial displacement has received the most attention in the literature, so we start by considering how this is estimated and discuss some of the associated issues. The typical approach taken is to observe changes over time (usually pre- and post-intervention) in a treatment area, a surrounding catchment area, and a suitable control or control areas. This is the most basic study design capable of detecting changes in the spatial distribution of crime following intervention. In our systematic reviews (Bowers et al. 2011; Johnson et al. 2012) of displacement, the effect size computed was the odds ratio,Footnote 1 and for each study identified, we computed one odds ratio to estimate the treatment effect and a second to estimate the extent to which spatial displacement or a diffusion of crime control benefits might have occurred.

In the case of area-based interventions, the odds ratio is computed using only four numbers, these being the counts of crime in the treatment (or a catchment area if estimating the extent of spatial displacement) and a suitable control area before and after intervention. The odds computed refers to the ratio of the likelihood of a crime occurring in an area of interest before intervention to that afterwards, and the odds ratio is the ratio of these odds for the treatment (or catchment area) and the control area. In the event that the rate of crime (per unit time) departs from the counterfactual (i.e. assuming no effect of treatment), the odds ratio will differ from one. The statistical significance of the odds ratioFootnote 2 can easily be derived by computing the standard error of the estimate (e.g., see Lipsey and Wilson 2001) and then calculating an associated p-value.

Table 1 shows the overall mean effect sizes for three of the meta-analytic studies discussed above (Bowers et al. 2011; Johnson et al. 2012; Braga et al. 2012). It is evident that, for each of the reviews, it appears to be the case that a diffusion of crime control benefits was at least as likely as spatial displacement. Moreover, that this was consistently the case for those primary studies of the highest methodological adequacy (i.e. that employed a randomized control design). It is worth noting, however, that the estimates are not entirely independent as some of the same studies were included in each of the three reviews. The reason for this is that, whilst the three reviews had slightly different foci, some of the primary evaluation studies were included in more than one of them.

As discussed above, one advantage of meta-analysis is that it increases statistical power. By comparing the effects of intervention in a treatment area and a catchment area independently, however, it is possible that, if the effect is not limited to the treatment area, researchers may fail to detect the overall effect of intervention. That is, even if the effects observed in the treatment or catchment area fail to reach statistical significance, the overall effect (if there is one) in the two areas combined might do so. If, as predicted by theory (Clarke and Weisburd 1994), offenders are probably not affected by the exact boundaries that delineate a treatment and catchment area, it seems reasonable to ask why the evaluator should be? Thus, we suggest that, as well as examining changes in the risk of crime in the two types of areas independently, evaluators might also seek to estimate the net effect of intervention across the two.

This could be achieved using the odds ratio approach discussed above, or using an alternative method proposed by Eck and Johnson in Clarke and Eck (2003, step 45), the aim of which is to estimate the total net effect of intervention, expressed as formula (1).

where

- TNE:

-

is the total net effect

- TRTt :

-

is the count of crime in the treatment area during time period t

- CTRLt :

-

is the count of crime in the comparison area during time period t

- CTCHt :

-

is the count of crime in a catchment area during time period t

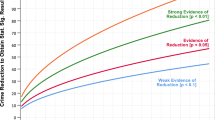

This provides an estimate of the actual amount of crimes prevented by an intervention, which is rather easier to understand than a change in odds. The estimates are also standardized which makes them suitable for inclusion in meta-analytic studies. In addition to computing a point estimate of the net effect, confidence intervals can easily be derived using a non-parametric bootstrapping approach (for a discussion, see Bowers et al. 2010). However, the estimation of such net effects should be applied with some caution. For example, changing the size of the catchment area could influence estimates quite considerably (see Openshaw 1984). Too small a catchment area may produce a conservative estimate by overlooking changes that occur further away from the treatment area. For such reasons, we suggest that where net effects are estimated—unless there is a good reason not to do so—the evaluators should conduct a sensitivity analysis to examine if and how estimates vary for different (sizes of) catchment areas.

Spatial patterns

Rarely have studies examined more nuanced changes in spatial patterns of crime post intervention than have already been discussed, but a few have. For example, some studies (Johnson et al. 2001; Bowers et al. 2003) have examined how rates of crime have changed following the implementation of situational crime prevention interventions across a series of mutually exclusive catchment areas that surround a treatment area. In the two studies considered, a diffusion of crime control benefit was (most) evident in the areas immediately adjacent to the treatment areas, with the effect decaying with increased distance. This finding is not only consistent with the rational choice perspective and theories of offender mobility, but also has practical implications. For example, if it is possible to estimate the distance over which a diffusion of crime control benefit is most likely, resources can be deployed so as to maximize this impact more cost effectively. However, findings such as these are scarce and hence it is unclear as to whether they are typical, for what types of crime they are observed, and if they vary across locations or interventions. Thus, more research with analytic designs sensitive to these issues is necessary if we are to truly understand the (side) effects of intervention.

In addition to displacing to locations near to treatment areas, where it does so, crime may be displaced or benefits diffused within treatment areas or to areas considerably further away. For example, in their evaluation of a large-scale operation (Operation Achorage), Ratcliffe et al. (2002) looked at how the point-pattern of crime events changed post-intervention within their study area. Their results suggested that, within the large region of intervention studied, crime had reduced overall, but the pattern of crime within the area had remained the same. The lack of re-distribution of the point pattern suggested that there had been no internal displacement of the crime problem.

Such analysis (see also Bowers et al. 2003) provides a better understanding of the effects of intervention that might inform policy or tactical decision-making. Like the studies discussed above, the analytic design employed in this study allowed for a more subtle test of how the spatial distribution of crime changed post-intervention. However, most studies are simply not designed to detect such changes, but if research is to influence crime reduction practice, they will need to be.

As alluded to above, the likelihood of crime occurrence may also be affected at locations that are neither within a treatment area, nor near to it. Considering offender mobility, spatial econometric studies of offender spatial decision making (e.g., Bernasco and Nieuwbeerta 2005; Bernasco and Block 2009; Johnson and Summers 2014) suggest that, all other things being equal, offenders prefer to commit offenses close to their home location, even for extreme events such as riots (Baudains et al. 2013). Moreover, the analysis of offender crime series suggests that, for acquisitive crimes at least, most offenses are committed near to each other (e.g., Johnson 2009). Such findings suggest that—consistent with the principle of least effort (Zipf 1949)—offending is typically local and patchy (see Johnson 2014), and hence that, if deterred from committing crimes at one location, offenders are most likely to offend at other areas nearby rather than searching for new opportunities further afield.

However, when prevented from committing crime at preferred locations, (at least some) offenders may choose to do so at other locations within their routine activity spaces. For example, in his study of offender spatial decision-making, using a spatial econometric model, Bernasco (2010) shows that, all other things being equal, upon release from prison offenders were more likely to commit crimes near to their current home location, but also near to previous home addresses.

Examining such patterns would require a different approach to analysis than is currently taken in evaluation research. Current studies are designed to detect changes in the rate of crime (before and after intervention) in locations proximate to an intervention area. Causality is inferred if any changes observed are coincident with intervention, but not observed in other comparable areas. Given that most changes are (theoretically) anticipated to most likely occur in the areas closest to intervention sites, this is a logical approach. However, if crimes were displaced (or benefits diffused) over a larger area, it would be difficult to detect such effects using such an evaluation design. One problem would involve detecting the “signal” from the “noise” as effects are likely to get “washed out” as the area considered increases (see Weisburd and Green 1995; Bowers and Johnson 2003). Another concerns the attribution of cause and effect, as this will likely be less convincing where changes are observed over large areas unless an intervention were implemented on a large scale.

Two approaches may help to solve this issue. The first would be to examine the spatial distribution of crime for more than two points in time. For example, a formal time series analysis of changes in spatial patterns of crime—in discrete catchment areas around a treatment area—that are coincident with the timing of intervention would allow for an estimation of the spatial extent of any displacement or diffusion of benefits that might occur. One problem with such approaches is that they will be more reliable where the rate of crime per unit time (per area) is relatively large. In many evaluations, crime rates are such that it is necessary for researchers to aggregate data to single before and after periods, or risk Type II statistical error (i.e. failing to reject the null hypothesis when there is actually an effect of intervention). And, consequently, this approach may not be feasible for the evaluation of anything other than large-scale interventions. Moreover, a time series approach such as this will only be convincing where the dosage of intervention varies over time, and data on implementation intensity are captured in a form that is suitable for analysis. For some evaluations, it may not be possible to capture such information, but there will be many interventions for which it is and we encourage researchers to consider this or similar approaches (for an example, see Bowers et al. 2004).

Where an RCT design is employed, some might wonder why it is not possible to simply examine changes in the catchment areas as the process of randomization will lead to equivalent groups. The problem, of course, is that, while the process of randomization will produce equivalence in the treatment groups, this is not the case for any catchment areas that surround it. These cannot be randomly allocated to a treatment or a control group and so there may be systematic differences in these and the areas to which they are compared, which necessitates the need for more complex analytic approaches.

A second, more direct, approach would be to either (1) interview active offenders (or somehow monitor their spatial behavior) to see how an intervention affects their spatial decision making; and/or (2) analyze data for offenses detected by the police to see if and how offender spatial decision making is affected by the timing and location of interventions. The latter might involve focusing on offenders known to offend in treatment areas prior to intervention and then contrasting their spatial patterns of offending before, during and after intervention. To our knowledge, offenders have been interviewed in only two studies to date (Weisburd et al. 2006; Matthews 1990). In the first, which concerned drug dealing and prostitution, offenders reported that they would not commit offenses elsewhere for reasons that included the risks of committing crime in areas perceived to be controlled by other offenders. In the second, street prostitutes reported that they desisted rather than displaced their activity following a crackdown in a London park, as the logical alternative prostitution area was too far and hence no longer worth the effort. Both these findings are consistent with the rationale choice perspective, but no studies of which we are aware have conducted such interviews for interventions that have targeted other types of offenses. Likewise, no studies of which we are aware have examined changes in offender mobility estimated using data for crimes detected by the police.

There are, of course, issues associated with the sampling design used in these kinds of studies. In the first instance, the issue is that since the population of offenders is unknown, there is no sampling frame from which to select offenders. Consequently, the recruitment of offenders would not be in anyway random, and would most likely rely on snowball sampling methods, which would lead to biased samples. In the second case, as most crimes go undetected, those offenders who are detected may not reflect the offender population in general which again can lead to biased samples (but see, Lammers 2014). Of course, these issues can be directed towards any studies involving offenders, and regardless of the identified issues, such studies would be informative and would allow us to see if—at least for the samples considered—whether patterns observed are consistent with the idea that offending may be displaced or benefits diffused over extended distances.

Crime Switch

Few studies have examined precise patterns regarding how the spatial distribution of (the same type of) crime changes post-intervention, but fewer still have examined changes in the distribution of other types of crime. Crime switch displacement is said to occur where reductions in one type of crime are accompanied by increases in another. One challenge in conducting such analysis is that different types of crime are not directly comparable. In the simplest sense, some crimes are more serious than others. From this perspective, one desirable outcome of an intervention might be to reduce one type of crime even this leads to an increase in another. If the former is more serious than the latter this would be an example of benign displacement (see above and Barr and Pease 1990). Leaving issues of intended outcomes aside, where crimes are not equivalent in scale or severity, quantitative analyses should be presented with caution so as not to suggest that they are. For example, one might estimate that an intervention prevented 100 burglaries but that this led to an estimated increase in 100 incidents of (say) pocket picking. In such a case, the change should be documented in a transparent way, but the researchers might seek to qualify the changes so that it does not appear that the positive intended effect of intervention was simply cancelled out by crime switch displacement.

Addressing such issues is complicated, and a number of approaches might be taken to tackle them. Here, we discuss one. First, for transparency and to allow the reader to review the portfolio of outcomes, we suggest that effects should be estimated for each crime type independently using traditional approaches with which readers will be familiar. Second, we suggest that consideration is given to economic approaches that seek to monetize the costs of crime (e.g., Farrell et al. 2004; Manning 2013). For instance, in the UK (e.g., Brand and Price (2000) have provided estimates of the costs of crime, both for those costs that can be readily identified and quantified (e.g., the value of property stolen) and those that are intangible (e.g., emotional and psychological costs). While imperfect, the use of such costs provides one way of converting effect sizes for different crimes to a common metric, thereby facilitating their comparison. For example, the estimated cost to society for 100 burglaries prevented can be contrasted with the cost to society of 100 incidents of pocket picking. Thus, converting effect sizes such as the net effect discussed above to monetized costs would provide one way of estimating the extent of crime switch displacement (or how serious the crime switch might be), as well as providing another lens through which to estimate the benefits of intervention more generally.

Temporal displacement

As discussed, criminal activity can also be displaced in time. For example, where interventions are operational during certain times of the day, days of the week, or weeks of the year, crime might be suppressed during their period of operation, but, where offender motivations are unchanged, crimes may be committed at other times with increased frequency. The analysis of such changes in crime patterns requires analysis of changes in the timing of offenses. Guerette and Bowers (2009) found that only 5% of the studies they identified explored the possibility of temporal displacement.

A number of different approaches could be taken to examine this issue and should be tailored to the specific research question of interest (is one considering hourly, daily, or weekly patterns, etc.). One approach, which uses a non-parametric permutation method to examine changes in the hourly distribution of crime, was introduced by Kurland et al. (2014). In their study, football matches were seen as analogous to an intervention that was hypothesized to increase crime. As football matches are episodic, in their study, Kurland et al. (2014) contrasted the rate of crime per hour of the day in the area that surrounded the stadium of interest on match days with the rate in the same area on comparable non-match days. The research showed that the hourly distribution of violent crime—summarized using an empirical cumulative distribution function (see Fig. 1)—differed on the two types of days, increasing in the hours just before the start of and during football matches on match (but not non-match) days. The statistical significance of any differences observed is trivial to compute and so a similar approach could be used in evaluation research more generally and could be used to look at other intervals of time.

Empirical Cumulative Distribution Function showing the fraction of violent offenses that occurred up to each hour of the day for match and non-match days (adapted from Kurland et al. 2013)

One issue with detecting changes in the timing of offences—at least using police recorded crime data—concerns the accuracy with which the time of offenses is recorded. This varies across crime types and evaluators should be cognizant of this. For crimes such as robbery, the victim will be aware of when the offense occurred as they will have been confronted by an offender at the time of the offense. For crimes such as burglary, however, victims are often absent at the time of an offense, sometimes for a period of days (burglars preferring to target unoccupied homes, e.g., Rengert and Waslichick 2000). Where this is the case, it will be difficult to establish precisely when an offense occurred. This would limit the accuracy or validity of any analysis of changes in the temporal pattern of crime conducted. For many types of crime, this will not be an issue, but for those where it is, care should be taken when interpreting results.

Target switch

Target switch is said to occur if those in receipt of intervention enjoy a reduction in crime risk whilst those who do not experience an elevation in the probability of victimization. Theoretically, this is most likely to occur (or be detected) where those who receive treatment differ systematically in observable ways to those who do not. In their review of situational crime prevention interventions, Guerette and Bowers (2009) found that only 14% of the examinations within studies assessed this form of displacement. The fact that previous studies have not typically examined this is no reason for future studies not to do so and consequently we consider this type of displacement briefly here.

In methodological terms, there are number of issues associated with estimating the extent to which such displacement may occur (or that benefits might diffuse to other targets). For example, over what geographical space and time should one look for target switch displacement?

Where those that do and do not receive treatment differ in identifiable ways, it may be possible to examine changes in crime risk for these two groups, or subsets of them. For example, where the two groups co-occur in a geographical area of intervention, analysis could usefully focus on the changes in risk to the two groups within this area. A detailed study of this was done for one burglary reduction scheme in Liverpool, UK. It demonstrated that in the particular case, benefits were enjoyed by both those properties that were directly targeted by intervention and those that were not but that were nearby. This is an example of diffusion of benefit to non-treated targets (Bowers et al. 2003). Where other forms of displacement or a diffusion of crime control benefit are detected, analyses of target switch might also be extended along the relevant dimension (s) – for example, in other nearby locations. Again, such analysis would provide a more comprehensive understanding of how the indirect effects of intervention influence crime risk. There is, of course, little value in examining this type of displacement (or diffusion) where there are no theoretical reasons for expecting it, so any analysis should start with a consideration of what is plausible.

Tactical switch

Tactical switch occurs where offenders, prevented from committing offenses in a particular way, commit the same crimes using different methods. Tactical switch may be subtle or may reflect a very different modus operandi. Regardless, the detection of this form of displacement requires an analysis of how crimes are committed and whether this typically changes post-intervention. Quantitative analyses of this form of displacement are rare. In their review, Guerette and Bowers (2009) found 49 examinations within studies that had considered this issue, but concluded that the evaluations were generally inadequately designed to allow a reliable estimate of the extent to which this did in fact occur. One exception is Bowers et al. (2004), who used a time-series design to examine if the point of entry used to commit burglaries in a treatment area changed following an intervention that restricted access to the rear of targeted households. Their analysis suggested that it did, with their being an increase in the frequency with which offenders gained access via the front of the property, or used other entry points. Interestingly, however, this effect was not observed immediately. Moreover, in the aggregate, crime reduced substantially in the same area, indicating that displacement can co-occur with net reductions (large in this case) in the same geographical area in the same period of time.

What is the onset and how long do effects persist?

With the exception of the study just discussed, a further unexplored issue in the literature concerns the timing of crime displacement or a diffusion of crime control benefits (where it occurs). As studies typically compare changes in rates of crime before and after intervention, studies have not typically explored if there is a temporal pattern to their occurrence. For example, crime control benefits (or displacement) may be observed immediately, or may materialize gradually. Similarly, effects may occur initially but fade over time. Furthermore, the two types of side-effect could co-occur with, for example, there being an initial diffusion of crime control benefits followed by crime displacement (or vice versa). More complicated regimes are, of course, possible. The detection of such effects would require the use of time series analyses designed specifically to detect them. More generally, the sustainability of the effect of crime prevention is a neglected topic in the evaluation literature. An exception of the latter can be found in Bowers et al. (2008), who use survival analysis to examine the impact of a situational crime prevention intervention and the duration of the effect observed.

Analytically, a time series approach could be used to examine the onset of effects by modeling the influence of an independent variable that indicated the time since the inception of an intervention. Theoretically, this would allow the researcher to detect if effects were immediate, or if they increased or decreased over time. Of course, effects may be non-linear and so researchers may want to use quadratic or polynomial forms in their equations.

A different approach might be used to examine how long effects persist. For example, for interventions that are temporary (e.g., police patrols) and can be introduced and then removed, an ABAB experimental design could be used to test the duration of treatment effects and any associated side effects. Such designs involve turning the intervention on and off in the treatment group (s) and observing the effects. By expanding the interval between pulses of the “treatment”, the longevity of the effect can be estimated (experimentally). However, such experimental methods will not be appropriate for all types of intervention (for a discussion of other methodological approaches, see Ekblom and Pease 1995).

What the current evidence base means for crime reduction efforts

Despite the shortcomings of existing crime displacement research, there is much that can be used to guide those who are concerned with crime reduction. Whether this be the criminologist who wishes to understand better the nature of offending, government leaders who wish to develop meaningful policies and programs, practitioners responsible for implementing them, or evaluators seeking to determine their full impact. As science is cumulative, at any given time those who must rely on scientific evidence, regardless of discipline or research focus, must do so with understanding of its evolutionary nature. Because of this, research-informed decision making must always be based on the best current available evidence. The scientific understanding of crime displacement offers no exception.

For future research, the opportunities to improve understanding of displacement are numerous but some seem more pressing than others. Much more needs to be known about the other forms of displacement such as tactical, target, and temporal. While these varieties have been understudied compared to geographic and offense, there is some indication that they may occur at greater rates. In one systematic review it was found that temporal displacement was examined in only 5 % of the inspections across studies yet was observed to occur 36 % of the time (Guerette and Bowers 2009). Similarly, target displacement was examined in only 14 % of the inspections but was observed to have taken place 33 % of the time. These proportions are much greater than for geographic displacement which was observed in only 23 % of examinations. Future research should also focus on detecting more distal crime movement as most studies have looked for displacement in the area immediately surrounding targeted areas. This may be most feasible with ethnographic research designs which track known offenders during and after intervention activities.

For evaluators of crime prevention initiatives the clear message of existing displacement research is that the possibility of crime movement and its better part, diffusions of crime control benefits, is very real. This has direct consequences for understandings of overall program impacts and because of this, future evaluations of relevant crime prevention initiatives should utilize research designs which account for the possible presence of displacement or diffusion effects as a fundamental requisite. Failure to do so leaves much to be known about true program impact and opens the door for criticism and dismissiveness of well-intended efforts. Just one example of the now integral aspect of displacement and diffusion determinations in evaluation design, is highlighted by the U.S. Department of Justice’s, CrimeSolutions.gov evaluation review protocol which gauges evaluations on their ability to reveal and account for displacement or diffusion effects in determination of overall program impact.

There is also opportunity for researchers and evaluators to improve on the methods to detect and measure crime displacement. The majority of research that has assessed for the presence of displacement and diffusion effects considered changes in treatment, catchment and control areas independently of one another. But in order to better understand the “net effect” of individual crime reduction initiatives, observed reductions in crime in target areas must be weighed against observed changes in catchment and control areas. This allows for a more complete and concise determination of overall program effects which will be more useful for not only those involved in specific projects but also for those who seek to replicate those initiatives in their own jurisdiction.

Moreover, one observation from the NPIA-funded systematic review (and others) is that it was not possible to include many studies in the meta-analysis. This was because many study authors did not report standardized test statistics that were suitable for statistical synthesis, or simply reported insufficient information. Thus, more consideration needs to be given to the use and reporting of standardized metrics in primary evaluations. This may require even more thought in studies that consider displacement as well as the intended outcomes of interventions.

Additionally, most current measurements of crime displacement can only suggest that there is evidence consistent with either the presence or absence of crime movement. This is because the ability to attribute causality regarding crime increases in nearby target areas where reductions were observed remains mostly unaccounted for in most research designs. This does require an extra level of complexity but it is not unattainable. One way to do this entails the use of four distinct areas to evaluate both crime reduction impact and any subsequent crime movement. The fourth area would be a catchment area around the control area to compare against observations in the catchment area around the target area which is intended to measure the presence of geographic displacement. A few studies have utilized the use of a control catchment area and while doing so has not been found to produce overall different results (see Bowers et al. 2011), it does seem to produce smaller mean effect sizes of interventions which may be more accurate and may provide a stronger basis for causality of any observed displacement or diffusion effects.

A related area for improvement involves how potential displacement areas are selected. Most existing research allocated the circumference zone around the targeted areas to detect any crime movement. It is likely, however, that any displaced crime will not move into that circumference area equally but may only exhibit itself in one portion within that circumference, or not it all. Future evaluations should apply some logical criteria informed by crime pattern theories to determine areas that may be more suitable for displacement or diffusion to occur rather than treating the surrounding environment as homogeneous in crime opportunity structure (see Eck 1993) and accessibility.

Extending from this, much more exploration is needed to understand the factors which contribute to the presence of displacement and diffusion effects. Crime opportunity theory suggests that whether or not displacement occurs will be determined by three primary factors: offender motivation, offender familiarity, and crime opportunity (Cornish 1994; Cornish and Clarke 1987; Eck 1993; Gabor 1990; for synthesis, see Guerette 2009). In part, these theories posit that offenders with high motivation and high familiarity of offending skill sets who are situated among other suitable crime opportunities which fulfill their needs and desires will be more likely to displace their crime behavior following prevention activities than those with low motivation and familiarity. The scientific effort to utilize these theories in the application of crime displacement research, however, remains inductive. To date there have been few, if any, deductive examinations of displacement tendencies which formally test these theoretical propositions.

For policy makers the available crime displacement research offers a firm basis for formulating meaningful policies and programs designed to reduce crime. This is why the NPIA commissioned the Bowers et al. 2011 review, and the Campbell collaboration continue to encourage further reviews involving the measurement of displacement. Prevailing findings give policy makers credible evidence to stave off criticism from those who might argue that place-based programs and practices will do little else than to displace crime. There is more to support the notion that the opposite is true even with the collective caveats reported here. There remains no collective scientific evidence that displacement happens as easily and universally as critics frequently claim. The available research also offers to educate policy makers on the incremental nature of crime reduction practice. Recognizing at the forefront that there are no “silver bullets” in crime reduction allows policy makers to temper expectations and outline realistic policy and program goals. It should also prompt government leaders to build in evaluation components to programs and policies in order to determine impacts.

For practitioners, it is equally important to be aware of the research evidence in order to stem criticism of prevention activities from community members. At the same time practitioners should be mindful of the possibility for displacement when formulating their crime prevention plans and ensure that tactics used are based upon a sound and complete understanding of the crime problem they are trying to address. Incomplete analyses of the problem or narrowly focused police crack downs are more likely to experience displacement effects (Bowers et al. 2011, 2010). Recognizing possibilities for displacement also allows practitioners to anticipate its occurrence and build in appropriate responses to the overall strategy at the outset.

Summary and conclusion

This article sought to synthesize the existing knowledgebase regarding crime movement; that is, the tendency of crime prevention initiatives to displace crime or diffuse crime reduction benefits. In doing so it outlined the theoretical rationale for why displacement would not be expected and reported on findings of recent systematic reviews, such as the Bowers et al. (2011) NPIA-funded review, which assessed for displacement effects in the evaluation of crime prevention schemes. Much progress has been made in displacement research over the last 30 years. While naysayers have long argued against the feasibility of preventing crime through opportunity reduction on the basis that crime will simply relocate, there now exists more scientific evidence negating these claims than there is in support. Theories of crime, as opposed to those of criminality, help to explain why crime displacement is not universal. Because crime opportunity is concentrated across time and place and offenders perceive these differential opportunity structures, it is understandable why crime does not simply “move around the corner” in the aftermath of focused prevention efforts.

The article also assessed the limitations of methods which have historically and recently been used to assess crime (dis)placement. As seems to be true in most research domains, our ability to develop better understanding of the crime displacement phenomenon is hampered more by our abilities as researchers to adequately measure and detect crime movement than it is by lack of imagination. Yet, given these limitations, there do seem to be some opportunities for the use of other existing research designs which could be relied upon to further understandings of crime movement in its various forms, in the near term. For instance, in Table 2 several possibilities are presented. These include the common pre-post and time series designs focusing on other displacement varieties, in addition to prospects for the use of point pattern, space-time, economic, and survival analyses. There are also varieties of crime (dis) placement which would be best understood through the use of qualitative or ethnographic methods. It is worth mentioning that whilst the most appropriate methods might differ for the distinct forms of displacement, it would be useful to consider the ease with which new effect sizes could be converted to a common metric, as this should help to facilitate the meta-analysis process.

Finally, the last section of the article considered the implications that existing displacement research offers not only for future researchers and evaluators of crime prevention initiatives but also for policymakers and crime prevention practitioners. In terms of the latter, it seems appropriate to also discuss displacement research as it relates to the broader evidence-based policy movement and the more recently coined term, translational criminology. If the purpose of evidence-based policymaking is to utilize scientific understanding in the formulation of effective crime prevention policy, then it is plausible that understanding of crime movement holds relevance. Certainly, it seems so for those policies which are directed toward the reduction of crime. Ignoring what we know and don't know about crime (dis)placement undermines the ability to formulate prevention initiatives that are likely to work. As such, failing to account for displacement and diffusion effects runs contrary to the very purpose of evidence-based policy and practice. It is partly because of this that we argue here that assessments of displacement and diffusion should become integral to all future evaluations of crime prevention outcomes.

The question then becomes whether or not the current body of knowledge regarding crime movement is sufficient enough to guide policy and practice. If that answer is yes, which we contend it is, then we can formulate and implement meaningful initiatives which substantively reduce the harms of crime with little chance of making things worse, or simply moving them around. Alternatively, if the current scientific body of understanding regarding crime movement is still too premature, then policymakers and crime prevention practitioners are left without a basis to predict when displacement is likely to occur and how to avoid it. They may also underestimate the true impact of their efforts should the likelihood of diffusion of benefits occur. Considering this, the benefits of utilizing displacement research in the formulation of evidence-based crime prevention policy seems to outweigh the potential costs. Whatever the outcome of future displacement research which may rely on refined research methods, it seems unlikely that the overall findings of existing research will be overturned. In that case, future refinements in methodology and measurement will only enhance our current understanding of crime (dis)placement and better equip those who are engaged in crime reduction efforts.

Notes

One issue with using this approach concerns the extent to which the parametric assumptions on which the method is based are reasonable (see Farrington et al. 2007). For instance, a key assumption is that the data generating process is a Poisson process. This may be reasonable for studies for which the unit of analysis is a person, but may not be for those for which the unit of analysis is a place (Marchant 2005; Farrington et al. 2007; Johnson 2009). The consequence of this is that the estimated standard errors and hence confidence intervals may be underestimated. For this reason, scholars (e.g. Farrington et al. 2007; Weisburd et al. 2008; Bowers et al. 2011) have typically multiplied the standard error by an inflation factor (often two) when calculating confidence intervals, which leads to a more conservative test. However, it is still possible that the true effect size will not be captured by the intervals derived, and hence when interpreting such findings, readers are advised to focus more on the general trends observed, their magnitude, and the overall conclusions that these might sensibly lead to rather than getting too caught up in the more absolute issue of statistical significance.

References

Barr, R., & Pease, K. (1990). Crime Placement, Displacement and Deflection. In Crime and Justice: A Review of Research, eds. Michael Tonry and N. Morris, Vol. 12. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Baudains, P., Braithwaite, A., & Johnson, S. D. (2013). Target Choice During Extreme Events: A Discrete Spatial Choice Model of the 2011 London Riots. Criminology, 51(2), 251–285.

Bennett, T., & Wright, T. (1984). Burglars on burglary: prevention and the offender. Aldershot, UK: Gower.

Bernasco, W. (2010). A Sentimental Journey To Crime: Effects of Residential History on Crime Location Choice. Criminology, 48, 389–416.

Bernasco, W., & Nieuwbeerta, P. (2005). How Do Residential Burglars Select Target Areas?: A New Approach to the Analysis of Criminal Location Choice. British Journal of Criminology, 45, 296–315.

Bernasco, W., & Block, R. (2009). Where Offenders Choose to Attack: A Discrete Choice Model of Robberies in Chicago. Criminology, 47, 93–130.

Bowers, K., & Johnson, S. (2003). Measuring the Geographical Displacement and Diffusion of Benefit Effects of Crime Prevention Activity. Journal of Quantitative Criminology, 193, 275–301.

Bowers, K. J., & Johnson, S. D. (2008). Evaluating crime prevention: the potential of using individual-level matched control designs. Policing, 2(2), 218–225.

Bowers, K. J., Johnson, S. D., & Hirschfield, A. F. G. (2003). Pushing Back the Boundaries: New Techniques for Assessing the Impact of Burglary Schemes. Home Office Online report 24/03. London: Home Office.

Bowers, K. J., Johnson, S. D., & Hirschfield, A. F. (2004). Closing off opportunities for crime: an evaluation of alley-gating. European Journal on Criminal Policy and Research, 10(4), 285–308.

Bowers, Kate, Shane Johnson, Rob T. Guerette, Lucia Summers, and Suzanne Poynton. (2010). “Systematic Review of the Empirical Evidence of Spatial Displacement and Diffusion of Benefit among Geographically Focused Policing Initiatives.” Report submitted to the Center for Evidence Based Crime Policy at George Mason University and the National Policing Improvement Agency (UK).

Bowers, K., Johnson, S., Guerette, R. T., Summers, L., & Poynton, S. (2011). Spatial Displacement and Diffusion of Benefits among Geographically Focused Policing Initiatives: A Meta-Analytical Review. Journal of Experimental Criminology, 7(4), 347–374.

Braga, A. A., Papachristos, A. V., & Hureau, D. M. (2012). The effects of hot spots policing on crime: An updated systematic review and meta-analysis. Justice Quarterly, (ahead-of-print), 1–31.

Brand, S., & Price, R. (2000). The Economic and Social Costs of Crime. Home Office Research Study 217. London: Home Office.

Brantingham, P. L., & Brantingham, P. J. (1981). Notes on the geometry of crime. In Brantingham, P. L., & Brantingham, P. J. (Eds.) Environmental Criminology. Beverly Hills: Sage.

Brantingham, P. L., & Brantingham, P. J. (1993). Environment, routine and situation: toward a pattern theory of crime. Advances in Criminological Theory, 5, 259–294.

Clarke, Ronald. V. (1983) Situational crime prevention: Its theoretical basis and practical scope. In Tonry, M. & Morris, N. (Eds.), Crime and Justice: An Annual Review of Research, vol. 4. Chicago: University of Chicago Press

Clarke, R. V., & Eck, J. (2003).Become a problem solving crimeanalyst in 55 small steps. http://www.popcenter.org/library

Clarke, R. V., & Weisburd, D. (1994). Diffusion of Crime Control Benefits: Observations on the Reverse of Displacement. In Crime Prevention Studies, ed. Ronald V. Clarke, Vol. 2. Monsey: Criminal Justice Press.

Cohen, L., & Felson, M. (1979). Social change and crime rate trends: a routine activity approach. American SociologicalReview, 44, 588–608.

Cornish, D. B., & Clarke, R. V. (1987). Understanding Crime Displacement: An Application of Rational Choice Theory. Criminology, 254, 933–947.

Cornish, D. B. (1994). “The Procedural Analysis of Offending and its Relevance for Situational Prevention”. in Crime Prevention Studies, Vol. 3, ed. R.V.. Clarke, Monsey: Criminal Justice Press.

Eck, J. E. (1993). The Threat of Crime Displacement. Criminal Justice Abstracts, 253, 527–546.

Ekblom, P., & Pease, K. (1995). Evaluating crime prevention. Crime and Justice, 585–662.

Farrell, G., Bowers, K., & Johnson, S. D. (2004). Cost-benefit analysis for crime science: making cost-benefit analysis useful through a portfolio of outcomes. In M. J. Smith & N. Tilley (Eds.), Crime Science. Cullompton: Willan.

Farrington, D. P., Gill, M., Waples, S. J., & Argomaniz, J. (2007). The effects ofclosed-circuit television on crime: meta-analysis of an English national quasiexperimentalmulti-site evaluation. Journal of Experimental Criminology, 3, 21–38.

Gabor, T. (1990). Crime Displacement and Situational Prevention: Toward the Development of Some Principles. Canadian Journal of Criminology, 32(1), 41–73.

Guerette, R. T., & Bowers, K. (2009). Assessing the Extent of Crime Displacement and Diffusion of Benefits: A Review of Situational Crime Prevention Evaluations. Criminology, 47(4).

Guerette, Rob T. (2009). “Analyzing Crime Displacement and Diffusion.” Problem- Solving Tool Guides for Police Series, U.S. Department of Justice, Office of Community Oriented Policing Services, Washington, D.C.

Hesseling, R. (1994). Displacement: A Review of the Empirical Literature. In Crime Prevention Studies, ed. Ronald V. Clarke, Vol. 3. Monsey: Criminal Justice Press.

Johnson, S. D. (2009). Potential uses of computational methods in the evaluation of crime reduction activity. In J. Knuttson & N. Tilley (Eds.), Evaluating crime prevention. New York: Criminal Justice Press.

Johnson, S.D. (2014). How do offenders choose where to offend? Perspectives from animal for aging. Legal and Criminological Psychology, in press.

Johnson, S.D., and Summers, L. (2014). Testing Ecological Theories of Offender Spatial Decision Making using a Discrete Choice Model. Crime & Delinquency, in press.

Johnson, S. D., Bowers, K. J., Young, C. A., & Hirschfield, A. F. G. (2001). Uncovering the True Picture: Evaluating Crime Reduction Initiatives using Disaggregate Crime Data. Crime a Prevention and Community Safety: An International Journal, 3(4), 7–24.

Johnson, S. D., Summers, L., & Pease, K. (2009). Offender as Forager? A Direct Test of the Boost Account of Victimization. Journal of Quantitative Criminology, 25, 181–200.

Johnson, S. D., Bowers, K. J., & Guerrette, R. (2012). Crime Displacement and Diffusion of Benefits: A Review of Situational Crime Prevention Measures. In B. Welsh & D. Farrington (Eds.), The Oxford Handbook of Crime Prevention. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Kurland, J., Johnson, S. D., & Tilley, N. (2014). Offenses around stadiums: a natural experiment on crime attraction and generation. Journal of Research in Crime and Delinquency, 51, 5–28.

Lammers, M. (2014). Are arrested and non-arrested serial offenders different? A test of spatial offending patterns using DNA found at crime scenes. Journal of Research in Crime and Delinquency, 51(2), 143–167.

Lipsey, M. W., & Wilson, D. B. (2001). Practical meta-analysis. Applied Social Research Methods Series, Vol. 49. Thousand Oaks: Sage.

Manning, M., Smith, C., & Homel, R. (2013). Valuing developmental crime prevention. Criminology & Public Policy, 12(2), 305–332.

Marchant, P. (2005). What works? A critical note on the evaluation of crime reduction initiatives.Crime Prevention and Community Safety, 7, 7–13.

Matthews, R. (1990). Developing more effective strategies for curbing prostitution. Security Journal, 1(3), 182–187.

Openshaw, S. (1984). The modifiable areal unit problem. Concepts and Techniques in Modern Geography, 38, 41.

Petticrew, M., & Roberts, H. (2006). Systematic reviews in the social sciences : a practical guide. Oxford: Blackwell.

Ratcliffe, Jerry H. (2002) Burglary reduction and the myth of displacement. Trends and Issues in Crime and Criminal Justice, Paper 232, August 2002.

Rengert, G. F. & Waslichick, J. (2000). Suburban burglary: a timeand a place foreverything. Springfield, IL: Charles Thomas.

Telep, Cody W., David Weisburd, Charlotte E. Gill, Zoe Vitter, Doron Teichman (2014). Displacement of Crime and Diffusion of Crime Control Benefits in Large-Scale Geographic Areas: A Systematic Review. Journal of Experimental Criminology (in press).

Weisburd, D., Wyckoff, L., Ready, J., Eck, J., Hinkle, J. C., & Gajewski, F. (2006). Does Crime Just Move Around the Corner? A Controlled Study of Spatial Displacement and Diffusion of Crime Control Benefits. Criminology, 443, 549–591.

Weisburd, D., & Green, L. (1995). Measuring Immediate Spatial Displacement: Methodological Issues and Problems. In Crime and Place. Crime Prevention Studies, eds. John Eck and David Weisburd, Vol. 4. Monsey: Criminal Justice Press.

Weisburd, D., and Telp, C. (2012). Spatial displacement and diffusion of crime control benefits revisited: New evidence on why crime doesn’t just move around the corner. In N. Tilley and Farrell, G. (Eds.). The Reasoning Criminologist: Essays in honour of Ronald V Clarke. London: Routledge

Weisburd D., Telep, C. Hinkle, J., & Eck, J. (2008). The efects ofproblem-orientedpolicing oncrime anddisorder. Oslo: Campbell Collaboration.

Yochelson, S., & Samenow, S. (1976). The Criminal Personality, Vol 1, A Profile for change. New York: Jason Aronson.

Zipf, G. K. (1949). Human Behaviour and the Principle of Least Effort. Oxford: Addison-Wesley.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License which permits any use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and the source are credited.

About this article

Cite this article

Johnson, S.D., Guerette, R.T. & Bowers, K. Crime displacement: what we know, what we don’t know, and what it means for crime reduction. J Exp Criminol 10, 549–571 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11292-014-9209-4

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11292-014-9209-4