Abstract

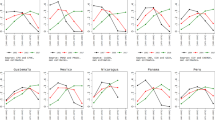

The aim of this paper is to analyse dynamically the three indicators of poverty and social exclusion covered by the EU2020 poverty target, while focusing on state dependence and feedback effects. We are interested in learning the extent to which the fact of being at risk of poverty, severe material deprivation or low work intensity in a given year is related to having the same status one year on, and whether being at risk in one domain in one year is a predictor of being at risk in one of the other domains in subsequent years. Our results are based on data from the EU-SILC for eight countries and indicate that the three social indicators of the EU2020 strategy capture different aspects of economic hardship in the majority of European countries analysed. We show that the three phenomena are affected by a considerable degree of genuine state dependence, but there is weak evidence for one-year lagged feedback effects—apart from in Hungary and Poland, where feedback loops between the three segments are to be found. Mostly, interrelationships occur at the same point in time via current effects, initial conditions and correlated unobserved heterogeneity. In terms of policy implications, our results suggest that the three phenomena should be addressed by different interventions while it is expected that spill-over effects across time will be marginal.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

For the detailed methodology of the composite and the three sub-indicators see http://ec.europa.eu/social/BlobServlet?docId=10421&langId=en.

See Pemberton et al. (2013) for a comprehensive review of the qualitative aspects of poverty persistence.

Oxley et al. (2000) contains further evidence in a comparative analysis of six countries on how the probability of exiting poverty falls with previous experiences.

See a brief discussion of the persistent material deprivation indicator from the ‘Social Situation Monitor’ at http://ec.europa.eu/social/main.jsp?catId=1050&intPageId=1997&langId=en.

Eurostat has only recently decided to include private pension plans as part of household income.

Using the same approach as other authors, missing values in the different deprivation items or activities are treated as no deprivation (see D’Ambrosio 2013).

Note the impossibility of adding controls relative to the labour market attachment of household members, as the low work intensity indicator (its initial condition and lagged value) captures part of this information.

The Nordic countries and the Netherlands have a sub-sampling procedure according to which they collect the variables of main activity status throughout the preceding year only for selected respondents aged 16+ in the sampled households, so the household work intensity variable cannot be calculated, as we do not have the information on other adults in those sampled households.

The only exception is the UK, which starts the panel with one rotational group less than the other countries.

The number of waves would have been too small for countries such as Bulgaria, Malta or Romania since they did not start their participation in the EU-SILC from the beginning.

Each point on the graphs presented in Sect. 4 shows the average across years (and not the average of annual rates).

We use this definition to proxy state dependence. Instead, Eurostat defines persistent poverty as the share of persons with an equivalised disposable income below the at-risk-of-poverty threshold in the current year and in at least two of the preceding three years. See http://epp.eurostat.ec.europa.eu/portal/page/portal/structural_indicators/documents/sc031_-_At_persistant_risk_of_poverty.

See Jenkins and Van Kerm (2014) for an in-depth analysis of the near-linear relationship between the current poverty rate and the persistent poverty rate (using the EU standard definition) with data from the EU-SILC.

The notation draws heavily on Ayllón (2015). See the same reference for a review of the previous literature that has used a similar model.

Note that such a panel structure makes it nearly impossible to include higher-order dynamics.

See Skrondal and Rabe-Hesketh (2014) for a recent review of the different strategies that have dealt with the initial conditions problem.

The full models with all the coefficients are available from the authors upon request and from the Web Appendix in www.saraayllon.eu.

For the sake of robustness, we ran another model, where the equation for severe material deprivation was the first one and that for poverty the second. This meant that, instead of capturing the effect of current material deprivation on poverty, we obtained the effect of current poverty on severe material deprivation. This model ensured that if a time bias relative to the reference period for poverty and material deprivation exists, no future values of material deprivation would enter as explanatory variable in the poverty equation. The results are very similar to those presented, with two main exceptions: we found a positive effect of current poverty on material deprivation in Italy, while the effect of lagged poverty on material deprivation in Poland was not found (we would like to thank Alessio Fusco (LISER) and Iva Tasseva (ISER) for suggesting this model structure to us).

Recall that Spain and Poland were the countries where the difference between the probability of being poor according to past low work intensity status was the smallest in Fig. 3c.

References

Alessie, R., Hochguertel, S., & Van Soest, A. (2004). Ownership of stocks and mutual funds: A panel data analysis. The Review of Economics and Statistics, 86(3), 783–796.

Amuedo-Dorantes, C., & Serrano-Padial, R. (2010). Labour market flexibility and poverty dynamics: Evidence from Spain. Labour Economics, 17(4), 632–642.

Arulampalam, W., Booth, A., & Taylor, M. (2000). Unemployment persistence. Oxford Economic Papers, 52(1), 24–50.

Arulampalam, W., Gregg, P., & Gregory, M. (2001). Unemployment scarring. Economic Journal, 111(475), 577–584.

Atkinson, T., Cantillon, B., Marlier, E., & Nolan, B. (2002). Social indicators: The EU and social exclusion. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Ayllón, S. (2013). Understanding poverty persistence in Spain. SERIES Journal of the Spanish Economic Association, 42(2), 201–233.

Ayllón, S. (2014). From stata to aML. Stata Journal, 14(2), 342–362.

Ayllón, S. (2015). Youth poverty, employment and leaving the parental home in Europe. Review of Income and Wealth, 61(4), 651–676.

Berthoud, R., & Bryan, M. (2011). Income, deprivation and poverty: A longitudinal analysis. Journal of Social Policy, 40(1), 135–156.

Biewen, M. (2004). Measuring state dependence in individual poverty status. Are there feedback effects to employment decisions and household composition? IZA discussion papers 1138, Institute for the Study of Labor (IZA).

Biewen, M. (2009). Measuring state dependence in individual poverty histories when there is feedback to employment status and household composition. Journal of Applied Econometrics, 24(7), 1095–1116.

Biewen, M., & Steffes, S. (2010). Unemployment persistence: Is there evidence for stigma effects? Economics Letters, 106(3), 188–190.

Boarini, R., & D’Ercole, M. M. (2006). Measures of material deprivation in OECD countries. Discussion paper, OECD Social, Employment and migration working paper series 37.

Cappellari, L., & Jenkins, S. P. (2004). Modelling low income transitions. Journal of Applied Econometrics, 19(5), 593–610.

Chamberlain, G. (1984). Panel data. In Z. Griliches & M. Intriligator (Eds.), Handbook of econometrics (Vol. 2, pp. 1247–1318). Amsterdam: North Holland.

Chzhen, Y. (2014). Child poverty and material deprivation in the European Union during the great recession. Innocenti working paper 2014-06, UNICEF Office of Research, Florence.

Copeland, P., & Daly, M. (2012). Varieties of poverty reduction: Inserting the poverty and social exclusion target into Europe 2020. Journal of European Social Policy, 22(3), 273–287.

Corluy, V., & Vandenbroucke, F. (2013). Individual employment, household employment and the risk of poverty in the EU. Methodologies and working papers, Eurostat, Luxembourg.

Corluy, V., & Vandenbroucke, F. (2014). Individual employment, household employment, and risk of poverty in the European Union. A decomposition analysis. In B. Cantillon & F. Vandenbroucke (Eds.), Reconciling work and poverty reduction: How successful are European welfare states?. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

D’Ambrosio, C. (2013). The indicators of intertemporal material deprivation: A proposal and an application to EU countries. ImPRovE discussion paper no. 13/08, Herman Deleeck Centre for Social Policy, Antwerp.

Devicienti, F., & Poggi, A. (2011). Poverty and social exclusion: Two sides of the same coin or dynamically interrelated processes? Applied Economics, 43(25), 3549–3571.

Dewilde, C. L. (2004). The multidimensional measurement of poverty in Belgium and Britain: A categorical approach. Social Indicators Research, 68(3), 331–369.

European Commission. (2006). Portfolio of indicators for the monitoring of the European strategy for social protection and social inclusion. Brussels: DG Employment and Social Affairs.

European Commission. (2009). Portfolio of indicators for the monitoring of the European strategy for social protection and social inclusion—2009 update. Brussels: DG of Employment, Social Affairs and Equal Opportunities.

European Commission. (2010). Europe 2020. A European strategy for smart, sustainable and inclusive growth. Brussels: Communication from the Commission COM(2010)2020.

European Commission. (2013). Social Europe. Current challenges and the way forward. Annual Report of the Social Protection Committee 2012. Brussels: EU Commission Working Document, Publications Office of the European Union.

European Commission. (2014). Taking stock of the Europe 2020 strategy for smart, sustainable and inclusive growth. Communication from the Commission to the European Parliament, the Council, the European Economic and Social Committee and the Committee of the Regions. Brussels: Communication from the Commission COM(2014) 130 final.

Eurostat. (2012). 3 % of EU citizens were at risk of poverty or social exclusion in 2010, Statistics in Focus 9/2012. Luxembourg: European Statistical Office.

Figari, F. (2012). Cross-national differences in determinants of multiple deprivation in Europe. Journal of Economic Inequality, 10(3), 397–418.

Fusco, A., Guio, A.-C., & Marlier, E. (2010). Characterising the income poor and the materially deprived in European countries. In A. B. Atkinson & E. Marlier (Eds.), Income and living conditions in Europe. Luxembourg: Publications Office of the European Union.

Fusco, A., & Islam, N. (2012). Understanding the drivers of low income transitions in Luxembourg. Research on Economic Inequality, 20, 367–391.

Goedemé, T. (2013). How much confidence can we have in EU-SILC? Complex sample designs and the standard error of the Europe 2020 poverty indicators. Social Indicators Research, 110(1), 89–110.

Guio, A.-C. (2009). What can be learned from deprivation indicators in Europe? Eurostat methodologies and working papers, Eurostat, Luxembourg.

Guio, A.-C., & Marlier, E. (2013). Alternative vs. current indicators of material deprivation at EU level: What differences does it make?. ImPRovE working paper series 13/07, Herman Deleeck Centre for Social Policy–University of Antwerp, Antwerp.

Guio, A.-C., Gordon, D., & Marlier, E. (2012). Measuring material deprivation in the EU. Indicators for the whole population and child-specific indicators. Eurostat methodologies and working papers, Eurostat, Office for Official Publications of the European Communities, Luxembourg.

Guio, A.-C., Marlier, E., & Pomati, M. (2014). Evolution of material deprivation over time: The impact of the great recession in EU countries. Paper presented at the 2014 international conference on comparative EU statistics on income and living conditions.

Hartfree, Y., & Collard, S. (2014). Poverty, debt and credit: An expert-led review. Discussion paper, Joseph Rowntree Foundation.

Jenkins, S. P. (2013). On state dependence: A case for two-handed economists. Discussion Paper 77, LASER, Labour and Socio-Economic Research Center.

Jenkins, S. P., & Van Kerm, P. (2014). The relationship between EU indicators of persistent and current poverty. Social Indicators Research, 116(2), 611–638.

Knights, S., Harris, M. N., & Loundes, J. (2002). Dynamic relationships in the Australian labour market: Heterogeneity and state dependence. Economic Record, 78(242), 284–298.

Lillard, L. A., & Panis, C. W. (2003). aML Multilevel Multiprocess Statistical Software (Version 2.0). Los Angeles, CA: EconWare.

Maître, B., Nolan, B., & Whelan, C. T. (2013). A critical evaluation of the EU2020 poverty and social exclusion target: An analysis of the EU-SILC 2009. GINI discussion paper 79, AIAS, Amsterdam.

Marlier, E., Atkinson, T., Cantillon, B., & Nolan, B. (2007). The EU and social inclusion: Facing the challenges. Bristol: Policy Press.

Mroz, T. A., & Savage, T. H. (2006). The long-term effects of youth unemployment. Journal of Human Resources, XLI(2), 259–293.

Muffels, R., & Fouarge, D. (2004). The role of European welfare states in explaining resource deprivation. Social Indicators Research, 68(3), 299–330.

Mullainathan, S., & Shafir, E. (2013). Scarcity. Why having too little means so much. London: Allen Lane, Penguin Books.

Nolan, B., & Watson, D. (1999). Women and poverty in Ireland. Dublin: Oak Tree Press.

Nolan, B., & Whelan, C. T. (2011a). The EU 2020 poverty target. GINI discussion paper 19, AIAS, Amsterdam.

Nolan, B., & Whelan, C. T. (2011b). Poverty and deprivation in Europe. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Oxley, H., Dang, T.T., & Antolín, P. (2000). Poverty dynamics in six OECD countries. Discussion paper, OECD Economic Studies No. 30, 2000/I.

Pemberton, S., Sutton, E., & Fahmy, E. (2013). A review of the qualitative evidence relating to the experience of poverty and exclusion. Discussion paper, Poverty and social exclusion in the UK—methods series no. 22.

Ravallion, M. (2011). On multidimensional indices of poverty. Policy research working paper 5580, World Bank Development Research Group, Washington, DC.

Sen, A. (1989). Development as capability expansion. Journal of Development Planning, 19, 41–58.

Skrondal, A., & Rabe-Hesketh, S. (2014). Handling initial conditions and endogenous covariates in dynamic/transition models for binary data with unobserved heterogeneity. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society: Series C (Applied Statistics), 63, 211–237.

Smith, J. P. (1999). Healthy bodies and thick wallets: The dual relation between health and economic status. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 13(2), 144–166.

Stewart, M. B. (2007). The interrelated dynamics of unemployment and low-wage employment. Journal of Applied Econometrics, 22(3), 511–531.

Townsend, P. (1979). Poverty in the United Kingdom. A survey of household resources and standards of living. Middlesex: Penguin Books.

Ward, T., & E. Özdemir (2013). Measuring low work intensity—An analysis of the indicator. ImPRove discussion paper no. 13/09, Herman Deleeck Centre for Social Policy, Antwerp.

Whelan, C. T., Layte, R., & Maître, B. (2003). Persistent income poverty and deprivation in the European Union: An analysis of the first three waves of the European community household panel. Journal of Social Policy, 32(1), 1–18.

Whelan, C. T., & Maître, B. (2007). Income, deprivation and economic stress in the enlarged European Union. Social Indicators Research, 83(2), 309–329.

Wooldridge, J. M. (2000). A framework for estimating dynamic, unobserved effects panel data models with possible feedback to future explanatory variables. Economics Letters, 68(3), 245–250.

Wooldridge, J. M. (2005). Simple solutions to the initial conditions problem in dynamic, non linear panel data models with unobserved heterogeneity. Journal of Applied Econometrics, 20(1), 39–54.

Acknowledgments

The research on which this paper is based is financially supported by the European Union’s Seventh Framework Programme (FP7/2012–2016) under Grant agreement No. 290613 (project title: ImPRovE). Sara Ayllón also acknowledges financial support from NEGOTIATE (Horizon 2020, Grant agreement No. 649395) and the Spanish projects ECO2013-46516-C4-1-R and 2014-SGR-1279. We would like to thank Tim Goedemé and Fabienne Montaigne for providing the do-file that helped us construct the low work intensity indicator. We are grateful to Karel Van den Bosch (Herman Deleeck Centre for Social Policy) and participants at the ImPRovE Meeting (Budapest, November 2014), at the SASE 2015 (London, July 2015) and at the SIS 2015 Statistical Conference (Treviso, September 2015) for their useful comments. We also want to thank the editor, Filomena Maggino, and one anonymous reviewer for helping us improving the paper. Any errors or misinterpretations are our own.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Ayllón, S., Gábos, A. The Interrelationships between the Europe 2020 Poverty and Social Exclusion Indicators. Soc Indic Res 130, 1025–1049 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-015-1212-2

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-015-1212-2

Keywords

- Europe 2020 indicators

- Poverty

- Material deprivation

- Low work intensity

- State dependence

- Feedback effects

- EU-SILC