Abstract

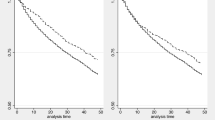

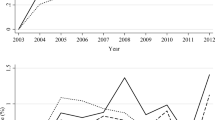

Research has recently emphasized that the non-survival of entrepreneurial firms can be disaggregated into distinct exit routes such as merger and acquisition (M&A), voluntary closure, and failure. Firm performance is an alleged determinant of exit route. However, there is a lack of evidence linking exit routes to their previous growth performance. We contribute to this gap by analyzing a cohort of incorporated firms in Japan and find some puzzles for the standard view. Our empirical analysis suggests that sales growth generally reduces the probability of exit by merger, voluntary liquidation, and also bankruptcy. However, the relationship is U-shaped—such that rapid growth actually increases the probability of exit. More generally, each of the three exit routes can occur all across the growth rate distribution. Large firms are more likely to exit via merger or bankruptcy, while small firms are more likely to exit via voluntary liquidation.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

The literature has even invented the concept of an “involuntary exit strategy,” although we doubt that something truly strategic can also be involuntary.

Given the scope of this paper, however, we do not investigate the determinants of startup size, but take startup size as given, and focus on post-entry growth and exit routes.

To be fair, this idea has been hinted at in the previous literature, e.g. Wennberg and DeTienne (2014, p9): “the type of exit routes available and the willingness to exit may differ significantly between lifestyle entrepreneurs and growth entrepreneurs.”

Moreover, we have another advantage to use COSMOS2 that firms’ status can be traced after firms’ relocation. In contrast, firms’ relocation is often regarded as exit from a region and entry into another region in government statistics, partly because the surveys are done by prefecture.

The credit investigation company asks the managers about the numbers for total annual sales, number of employees, profits etc., although the managers do not necessarily disclose the exact amount. So, the investigators usually attempt to obtain such information by a number of means, for example, by asking whether the number is same as the previous year. This explains why the number for sales is sometimes identical to the previous year (i.e. change of zero yen from one year to the next), and why we have a likely over-representation of annual growth rates of sales of exactly zero.

Note that the earliest years are not included in the regressions because these observations are lost due to the inclusion of lagged growth as independent variable.

For discussion of advantages of a discrete-time survival model, see Wiklund et al. (2010).

Regarding the effect size: Table 3 column (2) shows that if lagged growth increases by one standard deviation, then the change in the odds of exit via voluntary liquidation (compared to the benchmark case of survival) is 0.052 x (exp(−0.359) = 0.0363.

See Haans et al. (2016) for critical issues in theorizing and testing of quadratic relationships.

There is no clear cut-off point to distinguish between small and large firms because the firm size distribution in our sample is a continuous and approximately lognormal distribution (see Figure A1 in the Appendix). Therefore, we distinguish between small and large size subsamples by referring to the median size.

This effect is only found in the specification without quadratic terms for the second lag of growth. When quadratic terms are added, the coefficient is no longer statistically significant.

One potential drawback, however, of this alternative independent variable is that growth is measured over different growth periods across firms (e.g. time from startup to exit could be 2 years for one firm, and 6 years for another), and averaging over periods of different lengths could introduce bias. This could make it problematic to compare firms whose growth unfolds over different timescales (e.g. if rapid growth is harder to sustain over longer periods). This possible measurement error should be kept in mind.

References

Ahlers, G. K., Cumming, D., Günther, C., & Schweizer, D. (2015). Signaling in equity crowdfunding. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 39, 955–980.

Almus, M. (2004). The shadow of death - an empirical analysis of the pre-exit performance of new German firms. Small Business Economics, 23, 189–201.

Arora, A., & Nandkumar, A. (2011). Cash-out or flameout! Opportunity cost and entrepreneurial strategy: theory, and evidence from the information security industry. Management Science, 57, 1844–1860.

Bartelsman, E., Scarpetta, S., & Schivardi, F. (2005). Comparative analysis of firm demographics and survival: evidence from micro-level sources in OECD countries. Industrial and Corporate Change, 14, 365–391.

Baù, M., Sieger, P., Eddleston, K. A., & Chirico, F. (2017). Fail but try again? The effects of age, gender, and multiple-owner experience on failed entrepreneurs’ reentry. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 41, 909–941.

Bernard, A. B., Massari, R., Reyes, J. D., & Taglioni, D. (2017). Exporter dynamics, firm size and growth, and partial year effects. American Economic Review, 107, 3211–3228.

Blanchard, P., Huiban, J. P., & Mathieu, C. (2014). The shadow of death model revisited with an application to French firms. Applied Economics, 46, 1883–1893.

Botham, R., & Graves, A. (2011). Regional variations in new firm job creation: the contribution of high growth startups. Local Economy, 26, 95–107.

Brännback, M., Carsrud, A. L., & Kiviluoto, N. (2014). Understanding the myth of high growth firms: the theory of the greater fool. New York, Heidelberg, Dordrecht & London: Springer Science & Business Media. Springer.

Carreira, C., & Teixeira, P. (2011). The shadow of death: analysing the pre-exit productivity of Portuguese manufacturing firms. Small Business Economics, 36, 337–351.

Cefis, E., & Marsili, O. (2005). A matter of life and death: innovation and firm survival. Industrial and Corporate Change, 14, 1167–1192.

Cefis, E., & Marsili, O. (2011). Born to flip. Exit decisions of entrepreneurial firms in high-tech and low-tech industries. Journal of Evolutionary Economics, 2, 473–498.

Cefis, E., & Marsili, O. (2012). Going, going, gone. Exit forms and the innovative capabilities of firms. Research Policy, 41, 795–807.

Coad, A. (2014). Death is not a success: reflections on business exit. International Small Business Journal, 32, 721–732.

Coad, A., Frankish, J., Roberts, R., & Storey, D. (2013). Growth paths and survival chances: an application of Gambler’s ruin theory. Journal of Business Venturing, 28, 615–632.

Coad, A., Frankish, J. S., & Storey, D. J. (2019). Too fast to live? Effects of growth on survival across the growth distribution. Journal of Small Business Management, forthcoming.

Coad, A. (2018). Firm age: a survey. Journal of Evolutionary Economics, 28, 13–43.

de Jong, J. P., & Marsili, O. (2015). Founding a business inspired by close entrepreneurial ties: does it matter for survival? Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 39, 1005–1025.

Dencker, J. C., Gruber, M., & Shah, S. K. (2009). Pre-entry knowledge, learning and the survival of new firms. Organization Science, 20, 516–537.

DeTienne, D. R., & Cardon, M. S. (2012). Impact of founder experience on exit intentions. Small Business Economics, 38, 351–374.

DeTienne, D. R., McKelvie, A., & Chandler, G. N. (2015). Making sense of entrepreneurial exit strategies: a typology and test. Journal of Business Venturing, 30, 255–272.

Diwisch, S., Voithofer, P., & Weiss, C. (2006). The ‘shadow of succession’: a non-parametric matching approach. Mimeo.

Fackler, D., Schnabel, C., & Wagner, J. (2014). Lingering illness or sudden death? Pre-exit employment developments in German establishments. Industrial and Corporate Change, 23, 1121–1140.

Gimeno, J., Folta, T. B., Cooper, A. C., & Woo, C. Y. (1997). Survival of the fittest? Entrepreneurial human capital and the persistence of underperforming firms. Administrative Science Quarterly, 42, 750–783.

Graebner, M. E., & Eisenhardt, K. M. (2004). The seller's side of the story: acquisition as courtship and governance as syndicate in entrepreneurial firms. Administrative Science Quarterly, 49, 366–403.

Griliches, Z., & Regev, H. (1995). Firm productivity in Israeli industry 1979–1988. Journal of Econometrics, 65, 175–203.

Haans, R. F., Pieters, C., & He, Z. L. (2016). Thinking about U: theorizing and testing U-and inverted U-shaped relationships in strategy research. Strategic Management Journal, 37, 1177–1195.

Harada, N. (2007). Which firms exit and why? An analysis of small firm exits in Japan. Small Business Economics, 29, 401–414.

Harhoff, D., Stahl, K., & Woywode, M. (1998). Legal form, growth and exit of west German firms—empirical results for manufacturing, construction, trade and service industries. Journal of Industrial Economics, 46, 453–488.

Headd, B. (2003). Redefining business success: distinguishing between closure and failure. Small Business Economics, 21, 51–61.

Honjo, Y. (2015). Why are entrepreneurship levels so low in Japan? Japan and the World Economy, 36, 88–101.

Honjo, Y., & Nagaoka, S. (2018). Initial public offering and financing of biotechnology start-ups: evidence from Japan. Research Policy, 47, 180–193.

Ito, T. (2011). Reform of financial supervisory and regulatory regimes: what has been achieved and what is still missing. International Economic Journal, 25, 553–569.

Jovanovic, B. (1982). Selection and the evolution of industry. Econometrica, 50, 649–670.

Kato, M., & Honjo, Y. (2015). Entrepreneurial human capital and the survival of new firms in high-and low-tech sectors. Journal of Evolutionary Economics, 25, 925–957.

Kato M, Onishi K, Honjo Y, (2017). Does patenting always help new-firm survival? Discussion paper series no. 159, School of Economics, Kwansei Gakuin University.

Khelil, N. (2016). The many faces of entrepreneurial failure: Insights from an empirical taxonomy. Journal of Business Venturing, 31, 72–94.

Kiyota, K., & Takizawa, M. (2007). The shadow of death: pre-exit performance of firms in Japan. Discussion paper series no.204, Hitotsubashi University.

Klotz, A. C., Hmieleski, K. M., Bradley, B. H., & Busenitz, L. W. (2014). New venture teams: a review of the literature and roadmap for future research. Journal of Management, 40, 226–255.

Koski, H., & Pajarinen, M. (2015). Subsidies, the shadow of death and labor productivity. Journal of Industry, Competition and Trade, 15, 189–204.

Kubo, K., & Saito, T. (2012). The effect of mergers on employment and wages: evidence from Japan. Journal of the Japanese and International Economies, 26, 263–284.

Lansing, P., & Wechselblatt, M. (1983). Doing business in Japan: the importance of the unwritten law. The International Lawyer, 17, 647–660.

Lee, S. H., Peng, M. W., & Barney, J. B. (2007). Bankruptcy law and entrepreneurship development: a real options perspective. Academy of Management Review, 32, 257–272.

Lee, S. H., Yamakawa, Y., Peng, M. W., & Barney, J. B. (2011). How do bankruptcy laws affect entrepreneurship development around the world? Journal of Business Venturing, 26, 505–520.

Le Mens, G., Hannan, M. T., & Polos, L. (2011). Founding conditions, learning, and organizational life chances: age dependence revisited. Administrative Science Quarterly, 56, 95–126.

Levinthal, D. A. (1991). Random walks and organizational mortality. Administrative Science Quarterly, 36, 397–420.

Marlow, S., Mason, C., & Mullen, H. (2011). Advancing understanding of business closure and failure: a critical re-evaluation of the business exit decision. Paper presented at the Institute for Small Business and Entrepreneurship Conference 2011, Sheffield, 9–10 November, 2011.

Mehrotra, V., van Schaik, D., Spronk, J., & Steenbeek, O. W. (2008). Impact of Japanese mergers on shareholder wealth: an analysis of bidder and target companies. Erasmus Research Institute of Management (ERIM) Report Series, ERS-2008-032-F&A.

Miller, C. C., Washburn, N. T., & Glick, W. H. (2013). The myth of firm performance. Organization Science, 24, 948–964.

Parker, S. C. (2018). The economics of entrepreneurship. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Pe'er, A., Vertinsky, I., & Keil, T. (2016). Growth and survival: the moderating effects of local agglomeration and local market structure. Strategic Management Journal, 37, 541–564.

Peng, M. W., Yamakawa, Y., & Lee, S. H. (2010). Bankruptcy laws and entrepreneur–friendliness. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 34, 517–530.

Ponikvar, N., Kejžar, K. Z., & Peljhan, D. (2018). The role of financial constraints for alternative firm exit modes. Small Business Economics, 51, 85–103.

Porter, M. E., & Sakakibara, M. (2004). Competition in Japan. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 18(1), 27–50.

Ries, E. (2011). The lean startup: how today’s entrepreneurs use continuous innovation to create radically successful businesses. Crown Books.

Schary, M. A. (1991). The probability of exit. RAND Journal of Economics, 22, 339–353.

Sedlacek, P., & Sterk, V. (2017). The growth potential of startups over the business cycle. American Economic Review, 107, 3182–3210.

Shepherd, D., & Wiklund, J. (2009). Are we comparing apples with apples or apples with oranges? Appropriateness of knowledge accumulation across growth studies. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 33, 105–123.

Stinchcombe, A. (1965). Social structure and organizations. In J. March (Ed.), Handbook of organizations (pp. 142–193). Chicago: Rand McNally.

Storey, D. J. (2011). Optimism and chance: The elephants in the entrepreneurship room. International Small Business Journal, 29, 303–321.

Strese, S., Gebhard, P., Feierabend, D., & Brettel, M. (2018). Entrepreneurs' perceived exit performance: conceptualization and scale development. Journal of Business Venturing, 33, 351–370.

Tornqvist L., Vartia P., Vartia Y.O. (1985). How Should Relative Changes Be Measured? American Statistician 39, 43–46.

Villalonga, B., & McGahan, A. M. (2005). The choice among acquisitions, alliances, and divestitures. Strategic Management Journal, 26, 1183–1208.

Wennberg, K., & Anderson, B. S. (2019). Editorial: enhancing quantitative exploratory entrepreneurship research. Journal of Business Venturing, forthcoming.

Wennberg, K., & DeTienne, D. R. (2014). What do we really mean when we talk about ‘exit’? A critical review of research on entrepreneurial exit. International Small Business Journal, 32, 4–16.

Wennberg, K., Wiklund, J., Detienne, D. R., & Cardon, M. S. (2010). Reconceptualizing entrepreneurial exit: divergent exit routes and their drivers. Journal of Business Venturing, 25, 361–375.

Wiklund, J., Baker, T., & Shepherd, D. (2010). The age-effect of financial indicators as buffers against the liability of newness. Journal of Business Venturing, 25, 423–437.

Yamakawa, Y., & Cardon, M. S. (2017). How prior investments of time, money, and employee hires influence time to exit a distressed venture, and the extent to which contingency planning helps. Journal of Business Venturing, 32, 1–17.

Zhou, H., & van der Zwan, P. (2019). Is there a risk of growing fast? The relationship between organic employment growth and firm exit. Industrial and Corporate Change, forthcoming.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to Giulio Bottazzi, Elena Cefis, Masaru Karube, Francesco Lamperti, Sadao Nagaoka, Alessandro Nuvolari, and seminar participants at the Sant’Anna School of Advanced Studies (Pisa, Italy), the Innovation Economics Workshop, Hitotsubashi University (Tokyo, Japan), and University of Bergamo (Bergamo, Italy) for many helpful comments and discussions. Any remaining errors are ours alone.

Funding

Grant-in-Aid for Scientific Research (B) (No. 26285060) and (C) (No.18K01639), Japan Society for the Promotion of Science.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Appendix

Appendix

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Coad, A., Kato, M. Growth paths and routes to exit: 'shadow of death' effects for new firms in Japan. Small Bus Econ 57, 1145–1173 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11187-020-00341-z

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11187-020-00341-z