Abstract

The main aim of this paper is to act as a corrective to the comparatively deafening silence of egalitarian political philosophy’s response to the Great Recession. The paper thus provides an accessible analysis of a new strand of empirical research into the causes of the crisis. This new literature, which has largely gone unnoticed by the broader philosophical community, maintains that the main driver of financial instability is income and wealth inequality coupled with income stagnation at the bottom of the income distribution. Building on this empirical research, the paper puts forward six connections between egalitarian political philosophy broadly construed, and the findings of the new literature it surveys. These connections are understood as operating in two directions: that is, they both provide reasons for egalitarians to play a larger role in debates concerning the moral aspects of financial instability, and also offer valuable insights to egalitarians to reorient their position concerning central facets of their arguments.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

While there were some notable exceptions (see for example Dobos et al. 2011), the Great RecessionFootnote 1 has failed to generate widespread interest amongst egalitarianFootnote 2 political philosophers. This is not entirely surprising given the way in which most of the empirical literature elucidated the causal mechanisms that brought the economic system in the US (and, resultantly, much of the rest of the world) to the brink of collapse. Some of the most important themes with which egalitarians are concerned, such as the distribution of socially valuable resources,Footnote 3 did not appear to feature in the reconstructions provided by the empirical literature and presented in the public debate.

The main aim of this paper is to act as a corrective to the aforementioned lack of interest by showing that economic inequality has an important part to play in regard to the causes of the largest economic downturn since the 1930s. In order to do so, the paper provides an accessible analysis of a new strand of empirical research into the causes of the crisis. This new literature, which has largely gone unnoticed by the broader philosophical community, maintains that the main driver of financial instability is income and wealth inequality coupled with the stagnation of real incomeFootnote 4 for low- and middle-income groups. Building on this empirical research, the paper puts forward six connections between egalitarian political philosophy broadly construed, and the findings of the new literature it surveys. These connections are understood as operating in two directions: that is, they both provide reasons for egalitarians to play a larger role in debates concerning the moral aspects of financial instability and also offer egalitarians valuable insights in order to reorient their position concerning central facets of their arguments.

In elucidating the following six connections, the empirical narrative of the paper:

-

1.

reinforces the instrumental case against income and wealth inequality recently investigated by egalitarians (see O’Neill, 2010);

-

2.

provides further evidence of the centrality of the structural (as opposed to interactional) approach to the moral appraisal of economic cooperation;

-

3.

pushes egalitarians to deepen their concern for the relationship between equality of status and consumption choices;

-

4.

regarding the relationship between money and politics, invites a shift away from electoral politics and towards market regulation and the associated phenomena of regulatory capture;

-

5.

provides evidence that the egalitarian approach is important even from a broadly efficiency-friendly perspective; and, relatedly,

-

6.

shows that egalitarian approaches, by focusing on the implications of income and wealth inequality for financial instability, can offer a powerful rejoinder to recent realist critiques by pointing out that excessive levels of income and wealth inequality can potentially lead to losses of legitimacy and civic peace.

The paper proceeds as follows. Section 1 provides a short overview of the most commonly cited explanatory factors of the Great Recession, with a specific focus on the American financial system, which highlights a shared aspect of these explanations: the lack of a long-term perspective on the root causes that have allowed more proximate empirical phenomena within the financial system to act as triggers for the crisis. The principal empirical alternative is then presented. I start with a brief survey of the main indicators of income and wealth inequality coupled with the relative stagnation of low- and middle-income families (Sect. 2). I then move on to explain the connection between economic inequality and financial instability (Sect. 3). In Sects. 4–7 I explore the aforementioned connections between egalitarian political philosophy and the empirical narrative of the crisis presented in the first part of the paper.

The Usual Explanations and What they Fail to Tell Us

Most accounts of the Great Recession have tended to focus on the evolution of financial markets over the past three decades (see Lo 2012; Davies 2010; Muolo and Padilla 2010; Roubini and Mihm 2010; Jickling 2009; Posner 2009; Tett 2009; Morris 2008; Bitner 2008; Shiller 2008). Such accounts standardly recall the following factors: excessive build-up of systemic risk due to securitization; bad lending practices, especially in the real estate market (e.g. predatory lending); financial deregulation; poor oversight of existing regulators; flawed use of risk models and epistemic deficiencies more broadly construed; lack of transparency in financial instruments and markets (e.g. the use of complex derivatives contracts and ‘over the counter’ markets); technological innovation (e.g. computerization of financial markets); capital movement liberalization coupled with the rise of China and the global ‘savings glut’ determined by current account imbalances. If we look for explanations in terms of the organizational structures of large financial institutions and how they relate to the wider economic system we could also add: principal–agent problems in governance structures; flawed short-term systems of incentives for the institutions’ senior management; moral hazard caused by implicit guarantees provided to systemically relevant institutions (i.e. the ‘too big to fail’ problem); rating agencies’, accounting firms’ and financial firms’ multiple conflicts of interest.

A shared feature of these factors pertains to how financial markets have evolved over time. It is not surprising, then, that to the extent that political philosophy has been involved in the discussion, it has been limited to condemning specific practices within the financial system or, at most, to evaluating the broader context in which significant cases of moral hazard were allowed to develop (see Lomasky 2011). However, often evading public scrutiny, especially by those concerned with the moral problems exposed by the crisis, is the matter of situating the financial sector’s evolution in a long-term narrative. That is to say, even accepting that the Great Recession had its proximate causes in the financial system, one is entitled to ask why such evolutions have taken place. What the usual explanations of the crisis fail to provide is an account of the social, economic and political circumstances that led those factors (the proximate causes) to play the part they did in precipitating the crisis.Footnote 5 An alternative long-term structural explanation can be found in the relation, developed recently by a large body of empirical literature, between the income stagnation of low- and middle-income groups coupled with rising levels of inequality.

The Fact(s) of Rising Inequality

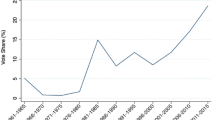

In most Western economies (and particularly that of the US), income and wealth inequality have been on the rise since the 1970s. The latter trend has been coupled with income stagnation for those in the middle and at the bottom of the income distribution (see Piketty 2014; Hager 2014). In order to gain a clearer picture of the magnitude of these phenomena, let us firstly consider income distribution. Professional economists often use the proportion of total income going to the top decile of the income distribution as a proxy for income inequality. According to Emmanuel Saez (2013), the top decile’s share of total income has been steadily increasing over the last forty years (see also Piketty and Saez 2003). In 2007 the top 10% in the US was enjoying the same share of total income as just before 1929—a proportion that is considered historically very high. Today, even accounting for the recent crisis, it is roughly 50% of total income. Professional economists and political scientists also refer to the Gini coefficient, a statistical technique that measures the dispersion between values in a frequency distribution, as a proxy for income distribution. When applied to income levels the Gini coefficient provides a comprehensive approximation of inequality, with 0 denoting perfect equality (i.e. everyone has the same income) and 1 expressing perfect inequality (i.e. only one person has all the income). The evolution of the Gini coefficient in the case of the US illuminates, once again, a relatively clear trajectory. According to the Bureau of Labor Statistics, the US’s Gini coefficient has changed from 0.385 to 0.470 over the last forty years. Though this may appear to be an insignificant variation, it should be borne in mind that the Gini coefficient is a very ‘dense’ tool to measure income inequality; most of the values the index can take are not, strictly speaking, economically or politically plausible.

Similar conclusions can be reached concerning wealth distribution. Let us consider wealth distribution in the US just before the financial crisis in 2007. According to Edward N. Wolff (2010), those in the bottom 40% of the wealth distribution controlled only 0.2% of total wealth, whereas the top 1% controlled 34.6%. Calculating the proportion controlled by the top 10% gives the staggering figure of 73.1% of total wealth. In the US, wealth inequality is even greater than income inequality. This is of course to be expected: wealth is always (historically) more concentrated than income, and in the absence of strong social mobility, four decades of increasing income inequality tends to reinforce wealth disparities over time (see Piketty 2014).

Finally, consider some of the data on income stagnation. Income inequality can be generated (conceptually) even in a society in which everyone is getting substantially richer. But in the case of the US in the last forty years or so, rising inequality has been coupled with a relative stagnation of the incomes of those towards the middle and bottom of the income distribution. Particularly striking is the disparity in the rise in real income for those in the bottom fifth of the income distribution (roughly 6%) compared with those in the top quintile (roughly 80%).Footnote 6 This trend has not been significantly affected by the recent crisis, nor by the earlier dot-com bubble, with the top 1% of the income distribution capturing 86.1% of real-income growth between 1993 and 2012 (Saez 2013). Whatever else these trends show, they allow us to see that the increases in income and wealth inequality constitute some of the most important structural changes in the US economy during the late twentieth and early twenty-first centuries.

The Inequality–Crisis Connection

The aforementioned trends are relatively clear. What remains to be seen is how economic divergence can create financial instability, and it is this to which I now turn. My analysis here builds on a growing literature that explores this link (Bazillier and Héricourt 2014; van Treeck 2014; Perugini et al. 2013; Wisman 2013; Holt and Greenwood 2012; Kumhof 2012; Maestri and Roventini 2012; Stockhammer 2012; Galbraith 2012; Atkinson and Morelli 2011; Lysandrou 2011).

The first way in which the connection between economic divergence and financial instability can be understood is by examining how inequality and stagnation trends help to generate demand for credit. When incomes at the bottom and middle of the income distribution are stagnating, goods often cannot be obtained with direct payments drawing on income; thus, access to credit is necessary in order for consumption (broadly defined) to be kept at stable levels (Wisman 2013). The prime example here is the housing market. When middle and low incomes stagnate, purchasing a house using income and savings becomes more difficult, and thus credit becomes increasingly important to achieve home ownership (see also Froud et al. 2010). In concrete terms, this demand (coupled with the demand for ‘durables’ such as cars, and the rising costs of college education) has shifted household debt in the US economy from 48% of GDP in the early 1980s to around 100% of GDP before the crisis (Milanovic 2009), at an estimated total value of $12.5 trillion in 2009 (Federal Reserve Bank of New York 2013). The idea that rising private debt will eventually lead to financial-market fragility is no cliché, but is widely accepted as credible (Rajan 2010; Reinhart and Rogoff 2009; Minsky 1986; Kindleberger and Aliber 2005 [1978]).

Secondly, income and wealth inequality also affect the demand for financial instruments, putting pressure on the financial system to innovate and diversify in order to allocate the surplus capital to be invested (Roemer 2012, p. 294; Galbraith 2012; Milanovic 2009). From a broadly Keynesian perspective (one in which individuals do not spend a fixed portion of their income independently of their income level and the general economic situation), those at the top of the income and wealth distribution tend to be comparatively less prone to consumption (i.e. they consume less as a proportion of their available resources). Thus, as income and wealth accumulate, the portion that is used for the purposes of consumption diminishes. While it is clear that the dynamics sketched here take time to come to bear on financial markets and eventually on the real economy, there is evidence that the long-term macroeconomic effects of a shock concerning relative incomes ‘increases credit demand at the bottom of the income distribution due to a consumption smoothing motive … [and at] the same time … it increases credit supply at the top of the income distribution due to a wealth accumulation motive’ (Kumhof 2012, pp. 5–6).

To this point the empirical analysis presented here has concentrated on consumption patterns and how they affect private debt accumulation. The analysis would not, however, be complete without commenting on the political context in which credit supply takes place. Some of the empirical analyses connecting inequality and income stagnation to private debt accumulation highlight the importance of institutional factors (Fitoussi and Saraceno 2010). Credit supply is clearly affected by the institutional context in which financial actors operate, and is profoundly shaped by government regulation and intervention. An important aspect of the institutional context affecting the supply of credit is the general trend in financial deregulation, which allows financial institutions to expand the supply of credit through financial innovation. By financial deregulation we can think of a regime of free international capital mobility coupled with decreased supervision by national regulators of major financial institutions. Examples include allowing traditional banks to invest deposits in speculative activities, permitting over-the-counter markets for derivatives and other complex financial instruments, and lowering capital requirements or weakening them by allowing the use of risk-weighted capital. In the same way, the supply of credit has also been shaped by direct government intervention affecting the housing finance market (particularly the implicit and explicit guarantees and incentives provided by the US federal government through the Federal Housing Administration, and the host of government-sponsored enterprises such as Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac) (Acharya et al. 2011).

In sum, the greater income and wealth inequality in the US over the past four decades has created a large divergence in economic holdings and income and wealth stagnation for those who are placed in the middle and at the bottom of the income and wealth distribution. In order to keep consumption levels stable, recourse to credit has rapidly increased, fuelled in part by the savings of those at the top of the income and wealth distribution, and encouraged by an institutional context favourable to the expansion of the credit supply.

What Kind of Egalitarianism?

Thus far I have used expressions such as ‘egalitarian’, ‘philosophical egalitarianism’ and ‘egalitarian political philosophy’ without providing a clear articulation of their meaning. And, as the liberal egalitarian church is such a broad one (White 2007), it seems particularly necessary to delineate the ‘egalitarian’ label I am employing here. It should be understood as referring to a broad range of approaches in moral and political philosophy that share a concern with status equality and political equality, and with the broader ideal of equal citizenship in which social, economic and political institutions express equal concern and respect for all individuals (Dworkin 1983).

In this picture, we see society as a fair scheme of social cooperation between free and equal citizens (Rawls 1971). The main social, political and economic institutions in society should be ordered according to principles of justice that mandate an equal scheme of basic liberties for all, and all citizens should have access to the means necessary to make use of the rights and liberties formally guaranteed by constitutional provisions (Rawls 1996). Furthermore, an egalitarian political community needs to provide a reasonable justification for how government policies affect its citizens (Eberle 2002). Social, political and economic institutions need to be organized in such a way that the reasonable interests of all members of society are given equal consideration: an ‘egalitarian deliberative constraint’Footnote 7 is at the heart of a conception of political community as a society of equals.

Whilst this vision does not mandate the equal distribution of income and wealth, it assigns great value to political and status equality. Political equality can be defined as the equal opportunity to influence political decision-making (and in particular, key aspects of the regulation of the economy) through broadly democratic deliberative procedures (Cohen 2009). Status equality can be defined as equality before the law and the protection of the basic constitutional liberties coupled with the ability of all citizens to conduct a materially dignified life (see Rawls 1971).

These definitions of political and status equality are parsimonious. They do not require equality of effective influence over political decision-making, or a specific kind of democratic process. Furthermore, they do not require equality in the distribution of socially valuable goods and opportunities, and neither do they specify a particular type of distribution for such goods. In the same way, the justificatory requirement I maintain to be at the heart of the egalitarian vision provides ample space for variations when it comes to the judgement of which policies can realistically be considered to give equal consideration to each citizen’s reasonable interests. Yet, while this conception of egalitarianism is underdetermined from a practical point of view, it does offer some guidance for the real world. It provides a clear sense of what is to be avoided and what we should consider as clear cases of injustice: inherited social hierarchies, overt political domination and immense differences in material possessions in the presence of persistent poverty are unacceptable (see Wolff 2015).

Some versions of egalitarianism—for instance, that which Martin O’Neill (2008) has cogently defined as non-intrinsic egalitarianism—would consider the aforementioned characteristics as part of the defining features of their approach. However, it is fair to say that most, if not all, of the positions that are traditionally considered to be ‘egalitarian’ in contemporary debates (e.g. luck egalitarianism) would likely find space for these ideals in a fuller articulation of their conceptions of persons and society. Following Sen (2009), one can say that egalitarian value commitments are often the result of different grounding strategies, and whilst egalitarians may disagree about which ground will be dominant in explaining the nature of egalitarianism, they will nonetheless accept that many, if not all, of those grounds can play some role in providing a full picture of their views.

What is the status of the connections between the empirical material that this paper has surveyed in Sects. 1–3 and the egalitarian political philosophy that has been elucidated in this section? The six connections that I will highlight below are not to be understood as unidirectional or as having linear implications. Rather, they should be seen as a network of links that allow egalitarians to reflect on the central elements of the Great Recession and at the same time on the status and defensibility of their concerns with income and wealth inequality.

Instrumental Egalitarianism and Structural Fairness

The first grouping of connections (i and ii) buttresses two important themes within egalitarian political philosophy, namely the focus on the effects of economic inequality, and the concentration on structural as opposed to interactional aspects of social and economic cooperation.

Let us begin with the first connection. A substantial and increasing corpus of recent academic literature has drawn attention to the negative effects of high levels of income and wealth inequality on such issues as social trust, mental health, life expectancy and infant mortality, obesity rates, children’s educational performance, teenage births, homicide levels, incarceration rates and social mobility (see Stiglitz 2012; Wilkinson and Pickett 2009). It should be abundantly clear that seeing these social phenomena as problematic does not require an egalitarian starting point. Taken together, however, they reinforce (instrumentally) the egalitarian normative case for controlling the level of income and wealth disparity (O’Neill 2010). What they tell us is that income and wealth inequality can have important negative effects on some of the central welfare indicators and social trends in a modern democratic society. If the results provided by the literature I have surveyed are correct, financial instability should be categorized as one of the central negative effects produced by economic inequality.

What is the relationship between these findings and the broadly egalitarian position I have outlined above? Some would argue that a purely instrumental account of the wrongness of inequality cannot give us the whole story. For one thing, there is a sense of contingency in any instrumental argument that will make many egalitarians uncomfortable. Simply put, a purely instrumental account of the value of equality would be hostage to the social scientific research outlining the consequences of income and wealth differentials. For another thing, some of the ways in which economic inequality can have negative effects are difficult to capture if one accepts a purely instrumental account of the badness of inequality. These effects pertain to how inequality affects the relationship between citizens in terms of their status and political standing, and reflect a background picture of political community as an association among equals. Nonetheless, even accepting that a purely instrumental case for the badness of inequality is incomplete, the fact that such a case does not necessarily rest purely on egalitarian foundations is a morally and politically relevant fact. Morally, it allows egalitarians to construct their concern about the badness of inequality as the focal point of an overlapping consensus between different types of public philosophies. To cite just one example, if the long-term effects of inequality have systematic implications for aggregate welfare, then it should not be difficult to convince utilitarians of its badness. Politically, it allows egalitarians to portray their concern for equality as being about a set of socially important and relatively concrete indicators that are part of persons’ everyday experience.

The second, and related, connection is that egalitarians can provide further evidence of the relevance of their long-standing preoccupation with the structure of social cooperation. Philosophical egalitarianism, at least of the (broadly) Rawlsian variety, can act as a strong corrective to the ways in which the public debate has addressed the ethical aspects of recent economic shocks. Thus far, much of the public discussion of the Great Recession’s ethical aspects has largely focused on memorable events such as Dick Fuld’s vilified congressional hearing, during which the former CEO of the collapsed Lehman Brothers defended his compensation packages (amounting over the years to more than $480 million), or Lloyd Blankfein’s infamous decision to allow Goldman Sachs to sell to its clients assets that the company itself did not believe to be financially sound. One of the main ethical threads running through reactions to these events was the deplorable moral character of those in the financial sector. Whilst the aforementioned reactions are understandable, it seems striking that the most important issues arising from such evidence as we have surveyed do not pertain to the moral pedigree of individual bankers, but to the structure of our social and economic life.

To put it a different way, our normative evaluations of bankers and financial institutions have, so far, mostly been driven by what some have called an interactional view of fairness (James 2012). On this view, we can essentially isolate the moral features of an action or agent and then judge them against our intuitive understanding of what is morally sound behaviour. For example, we have the intuition that individuals should not be rewarded for failure and that negative externalities should be internalized by economic actors. This seems to explain the outrage generated by bankers walking away with large compensation packages from collapsing or collapsed companies, but also the deeply negative views of the public support (e.g. the bailouts supported by taxpayers) received by several financial firms in the wake of the crisis.

Clearly, these judgements have a place within the moral narrative of the Great Recession. At the same time, given the explanation of the crisis I have sketched above, they do not tell the full story. If we take the crisis to be the result of long-term trends connected to rising inequality of income and wealth in the wider economy coupled with income stagnation for middle- and low-income households, the interactional normative benchmark will not be able to provide us with a complete moral evaluation of the economic system that generated the crisis in the first place. In other words, the interactional benchmark will simply be unable to shed light on why, for example, the financial system and its actors, from individuals to institutions, had the opportunity and the means to behave in the way that they did. The point is not to detract from the view that these agents could and should have acted differently, but rather to point out that they acted within a framework that was not necessarily simply of their own making.

The aforementioned points are, in many ways, at the heart of the Rawlsian edifice. Rawls (1971) famously argued that the primary subject of justice is the basic structure of society, namely the set of basic social and political institutions that make social cooperation possible. One reason to focus on the basic structure is that it has a deep form of impact on persons’ life prospects (that is, on how they will fare over the course of their lives) (Rawls 1971, pp. 3–7). A second reason is that it is difficult to fully judge the fairness of local agreements and individual transactions unless we know the general background conditions in which such agreements and transactions have taken place (see Rawls 1996, p. 267).

The more straightforward way in which the latter ideas apply to the context of the Great Recession is in the notion that, by concentrating on specific agents and actions, we are effectively missing out on the broader picture of how we have chosen to organize economic cooperation. And yet, following from the empirical material surveyed above, it is not far-fetched to claim that it is the structure of economic cooperation, rather than the behaviour of individual financial actors, that had the most profound effects on the genesis of the crisis. A second way in which Rawls’s insistence on the importance of the basic structure is relevant is that it allows us to grasp more fully the circumstances in which specific economic agents were placed and thus gain a more nuanced understanding of their behaviour.

Over the past few decades, egalitarians have tried to broaden their case against economic inequality (by citing what are often non-egalitarian arguments linked to the consequences of inequality) and to press home the point that one should concentrate on the structural aspects of social and political phenomena instead of singling out individual transactions and specific forms of behaviour in the economic sphere. The egalitarian approach could strengthen its appeal if it expanded its examples of severe negative effects caused by economic inequality to include the seismic economic events of 2007–08—the greatest downturn of the last sixty years which brought the world economy to the brink of collapse. In the same way, the egalitarian approach would be strengthened if it was able to provide a more encompassing moral narrative of individual failures and financial crimes highlighted by the Great Recession—a narrative that, hopefully, could plough a middle course between the uncharitable public lynching of individuals and the absolutory talk that insists that when all are guilty, no one can be blamed.

Status and Political Equality

The second set of connections (iii and iv) serves the purpose of reorienting some of the well-known egalitarian concerns regarding the effects of economic inequality on, on the one hand, equality of status and self-respect, and on the other, political equality. The empirical material surveyed above suggests that egalitarians should pay more attention to the effects of economic inequality on consumption choices given that they are often used to express status relationships. In the same way, egalitarians should attend more closely to the relationship between money and market regulation instead of concentrating on the effects of income and wealth inequalities on electoral processes: regulatory capture is the larger evil and provides the clearest example of how social and political domination can be exercised in a deeply unequal society.

Let me start by illustrating the third connection. It suggests that a broadly egalitarian political philosophy should pay more attention to the relationship between equality of status and aggregate consumption choices. According to most egalitarians, excessive differences in income and wealth can produce a sense of diminished self-respect for those who have less (Scanlon 2003), and may generate what Rawls calls excusable envy (1999 [1971], p. 468). Large economic inequalities tend to undermine citizens’ perception of themselves as equals before the law; they engender a sense of inevitability about one’s less favourable social and economic position; and can constantly remind the less well-off of the disparity in lifestyles and opportunities available to the different income groups in society (Tomlin 2008). However, while these reasons are well-understood aspects of the tension between economic inequality and equality of status, the links between the latter and consumption choices have not, so far, received the same level of attention. Yet my analysis suggests that the relationship between equality of status and economic inequality is central, and not simply (as many have claimed) in assessing the implications of large differences in material holdings for individual self-respect and ultimately well-being. Economic inequality, by affecting equality of status, may also affect the trends that pertain to the accumulation of private debt through consumption (and thus, following the empirical analysis presented above, the very stability of the economic system).

To be sure, substantiating the latter claim would require a much closer inspection of our normative attitudes towards consumption choices (Claasen 2014). Clearly, to see equality of status as completely defined by material possessions suggests an unattractive picture of social life as a zero-sum game (Schor 1998). However, we cannot simply discount the fact that most consumption choices are relational in character and are connected to the type of standing that individuals perceive themselves to have in society. This is for at least two reasons. First, the very idea of a decent standard of living is impossible to define without referencing the wider social and economic context (Lichtenberg 1996). Whatever is demanded by equality of status, materially speaking, it certainly requires citizens to lead dignified lives. However, to lead a dignified life clearly requires access to a set of material goods, and in turn, what is part of this set is bound to be affected by context, and more specifically, by what others in society ‘own’.

Second, at least in advanced capitalist economies, an increasing number of goods have positional aspects (Hirsch 1995 [1976]; Franck 2013).Footnote 8 Moreover, goods with positional aspects include several that affect people’s basic opportunities in social life, such as housing and, relatedly, access to secondary and tertiary education. In this picture, relational consumption choices can have a defensive purpose (Warren 2003). As I have said above, we tend to find the idea of social life as a zero-sum game morally unattractive. The basic problem is envy: we find envy morally distasteful,Footnote 9 and yet envy is precisely what seems to be involved in seeing gains (as defined by material possessions) that occur to others as losses to ourselves. Thus, in much of the classical literature on this theme (Rawls’s (1999 [1971]) and Gauthier’s (1987) work are the clearest examples here), the focus has been on how to define envy and then find a way to filter it out from political principles (Heath 2006). The basic reasoning seems to be that pernicious forms of ‘natural attitudes’ should not be allowed to influence public choices. Envy, much like cruelty, is an antisocial form of human emotion which no moral philosophy should give weight to, no matter how deeply and pervasively felt it happens to be (Heath 2006). Not only is envy ethically pernicious, no sincere form of community seems possible (or no community that recognizably strives for some form of political unity) if public policies are allowed to reflect it.Footnote 10

However, the problem with positional goods is precisely that, by definition, gains for others are losses to oneself with respect to the goods in question. Thus, when such goods grow in number and their role in determining people's life prospects becomes more important, a certain dose of ‘concern’ (for lack of a better word) for how others are faring seems justified.Footnote 11 A different way of putting the latter point is that, given the positional character of many basic goods and opportunities in social life, it is hard to classify those who are worried about other people’s resources and consumption as irrational and/or ethically pernicious. To resent others for what they have independent of how that affects us (other than by making us envious) is antisocial and irrational. But there is nothing antisocial or irrational in being concerned with what others have if that deeply affects what we can aspire to when it comes to basic goods and opportunities (Heath 2006). Am I claiming that subjective losses to well-being (as a result of positional competition) are sufficient grounds for egalitarian concern and public regulation?Footnote 12 Some clearly believe that they are. The losses in aggregate welfare stemming from positional competition are significant and this should be enough to justify policies such as, for example, targeted consumption taxes (Frank 2010). My claim is, however, more modest. The point I wish to make is that persons can have morally respectable reasons to participate in positional competition—and a recognition of these reasons does not require us to accept antisocial or irrational motives.

The fourth connection serves the purpose of reorienting the long-standing concern for equal political standing which animates much egalitarian political philosophy. More specifically, the egalitarian concern with the effects of money on politics needs to be more clearly oriented towards understanding the specific phenomena of regulatory captureFootnote 13 that shape key aspects of market regulation.

According to most egalitarian approaches, inequalities of wealth and income can have detrimental effects on the political process (Scanlon 2003; Beitz 2001; Rawls 2001; O’Neill 2008). More specifically, large imbalances in wealth and income can come to limit the range of available options for those who have less. Following Scanlon (2003; see also Rawls 2001), we can say that the wealthy can come to exercise an undue level of control over the outcomes of decision-making that affect the entire population. From the allocation of resources to public education to the extent of protection offered by the welfare state, the voice of the rich is often heard more loudly than the voice of the poor. Second, there is what Charles Beitz (2001) among others has called procedural unfairness. The latter refers to the conditions under which the deliberative and competitive processes that lead to decision-making take place. To use a familiar example, political campaigns in which private contributions can be unlimited will often disproportionately favour the election of officials closely aligned with the political agenda of well-off citizens (Cohen 2009, Chapter 8). Third, money can act as an agenda-setter because the ‘voice’ of those who are able to invest significant financial resources in political campaigns will tend to be associated with a higher likelihood of political success (Bartels 2008). Fourth, money can be an important way of creating support for one’s views in the public sphere and to lobby the legislative process (Christiano 2012, p. 247).

At the same time, a large part of the empirical literature on the causes of the crisis has focused on the deregulation of the financial system. As we have seen, many of the analyses within this paper’s broad framework point out that shocks to relative income affect demand for credit and for financial instruments, but that private debt accumulation cannot be fully explained in the absence of institutional factors that are favourable to the expansion of the credit supply. The question, then, is whether we can trace the decisions affecting those institutions favourable to the expansion of the credit supply to the concentration of resources at the top. This is a central tenet of some of the most powerful analyses of regulatory capture by the financial system (Canova 2009; Johnson and Kwak 2010; Kwak 2014). According to Simon Johnson and James Kwak, there is a long-standing and pervasive historical relationship between the financial sector and the political process, one in which the ‘political influence of Wall Street helped create the laissez-faire environment in which the big banks became bigger and riskier, until by 2008 the threat of their failure could hold the rest of the economy hostage’ (Johnson and Kwak 2010, p. 18). The point of paying more attention to regulatory capture is not to ask political philosophers to become political scientists. Rather, the basic idea is that the concern with equal political standing that animates much contemporary egalitarianism can be less abstractly and more powerfully articulated and illustrated if one attends to the structural relationships between private agents and their regulators in key economic sectors, rather than (simply stated) as referring to campaign financing and electoral processes broadly understood.

Efficiency and Ideal Theory

The last grouping of connections (v and vi) highlights the ways in which egalitarians can gain from the alternative analysis of the crisis that I have presented. Lack of concern for economic efficiency and the excessive moralization of political life have often been depicted as two of the least attractive features of egalitarian political philosophy. And yet the recent financial crisis, and the evidence that explains its causes in terms of the outcome of sustained economic inequality, may suggest that these concerns are overblown. The profound and lasting effects of the crisis on output and employment suggest a more nuanced view of the so-called trade-off between equality and efficiency. In a similar way, the crisis has dented the perceived legitimacy of the economic system as a whole and has thus reinforced the link between economic inequality and the (in)stability of political institutions.

Let me start with egalitarianism’s putative hostility towards efficiency. The empirical material we have surveyed in Sects. 1–3 tells us that increased economic divergence does not simply represent one of the morally problematic outcomes of the evolution of the US economic system over time, but one of the very causes of the crisis itself. This being so, egalitarian political philosophy could play a more extensive role in the analysis of modern economic systems. Its concerns need not be limited to the analysis of the fact of inequality from a moral point of view, but can be extended to the implications of such inequality and how they bear on economic stability. Put differently, a concern for economic inequality, at least in the context of a modern financialized economy, can be depicted as coextensive with a concern for the very functioning of the economic system, not simply the analysis of its moral features or properties. This, in the first instance, would allow egalitarians to deflect some of the typical concerns raised about their view of market capitalism. One particularly worrisome complaint is that being an egalitarian entails accepting a specific answer to what Okun (1975) famously called the trade-off between equality and efficiency—namely that we should sacrifice efficiency for the sake of equality.

Following Le Grand (1990), a well-established reply to the latter accusation has been to point out that the conflict between equity (here understood as a measure of equality) and efficiency is, at best, a conceptual confusion. If by efficiency we refer to the way in which we pursue several socially valuable objectives at the same time, then it is what we can call a second-order value: efficiency often describes how we pursue what we deem to be socially valuable not something we deem socially valuable per se. If we accept this understanding of efficiency, then there cannot be a trade-off between efficiency and equity. However, even if we reject Le Grand’s argument, the recent financial crisis has highlighted something important about the (putative) trade-off between equality and efficiency. If the link between economic inequality and financial instability is robust, then the trade-off may, in the end, be far less (empirically) acute than many have thought. More broadly, being egalitarians may not require us to lose sight of the value of economic efficiency or the relevance of aggregate welfare. On the contrary, it may be the case that, at least with regard to the current distribution of resources in several Western economies, paying attention to efficiency and aggregate welfare requires us to use criteria of institutional evaluation that are concerned with relative economic standing. In other words, we may need to pay attention to equality for the sake of efficiency.

Of course, the latter will depend upon which definition of efficiency we draw upon and for what purpose (Buchanan 1985). For example, using the traditional Pareto criterion to argue in favour of the reduction of income and wealth dispersion is clearly a conceptual non sequitur. If financial instability is the long-term result of inequalities in wealth and income, and assuming that at least some reduction of economic inequality would be necessary to tame this structural connection, it is unlikely that everyone would be better off as a result.Footnote 14 However, an argument for a more egalitarian society being attuned to a concern for efficiency could be formulated by using the weaker (and usually much more realistic) Kaldor–Hicks criterion. To be sure, it would be a highly speculative exercise to counterfactually prove that, other things being equal, a less unequal economic system is more efficient as per the Kaldor–Hicks criterion. Nonetheless, it is far from inconceivable that the counterfactual question about comparative efficiency could be answered in favour of a more egalitarian distribution of income and wealth given the extensive losses of output and employment that generally follow in the wake of banking crises and financial distress.

Relatedly, the sixth connection is that egalitarian political philosophers can call attention to how their concerns for relative economic standing need not be grounded solely in reasons that pertain to ideal theory. In recent years, political philosophers have been increasingly preoccupied with methodological questions related to the development of normative principles. One way to frame this debate is to see it as a discussion pertaining to the relative merits of ideal and non-ideal theorizing. The distinction between ideal and non-ideal theorizing is, however, a multifaceted one.Footnote 15 By ideal theory we can refer to those theories that presuppose full compliance with the content of the principles for which the theory argues. In this picture, a non-ideal theory would then refer to a theory that works under the assumption of partial compliance. A second sense in which a theory can be ‘ideal’ is by aiming to describe some form of perfectly just state of affairs. Here, a non-ideal theory would instead concentrate on transitional aspects of political morality – that is, on providing guidance to make incremental (normative) progress possible without necessarily trying to define what a perfectly just society looks like. Finally, a theory can be ideal because its prescriptions are utopian in the sense that they reject the idea that facts about human psychology and political reality can act as constraints on the content of basic political principles. In this final sense of the term, a non-ideal theory is simply a kind of theory that allows (at least some) political circumstances to influence the content of its prescriptions.

The recent debate between so-called liberals and so-called realists has also highlighted a fourth sense in which mainstream political philosophy fails to be political in the right way (see for example Horton 2010; Rossi and Sleat 2014). Egalitarian liberalism, it is often said, is tantamount to an artificial moralization of political life, one that simply fails to attend to a proper political morality and the nature of politics itself. One of the favourite targets of these complaints is the concern for justice and equality. However, if the evidence I have surveyed is sound, the concern for equality is not simply about the correct understanding of justice in ideal theory, but can be translated into a concern for stability and legitimacy.Footnote 16 An economic system that is characterized by significant economic inequality may lead to recurrent financial instability. In turn, the losses of output and employment that are associated with these episodes of financial instability will put pressure on the support that ordinary citizens need to provide to their social and political institutions, and which is necessary for the ongoing process of social cooperation to continue peacefully over time. In other words, the concern regarding the levels of material equality that are prevalent in a democratic society cannot simply be depicted as idealistic fantasy superimposed on real politics from the ivory tower of academic debate. If civic peace and legitimation are central to a more realistic understanding of political life, then a concern with the level of material differences in a modern financialized economy may simply be something that we are required to develop. Of course, the latter point will not necessarily settle the debate between egalitarians and realists: egalitarians may still care about equality and see stability and legitimacy as merely having derivative status as by-products of a more equal society. Realists may still see the value of equality as merely instrumental. Nonetheless, it would highlight that the potential for reconciliation is higher than what may have initially been thought.

Conclusion

The overall aim of this paper has been both reconstructive and explorative. I have attempted to highlight the link between a specific account of the Great Recession that is increasingly gaining purchase in the empirical literature, and philosophical egalitarianism. Elucidating these connections should lead us, I hope, to ask different questions about the economic and political context that preceded one of the worst economic shocks since the 1920s.

Notes

A recession is usually defined as a generalized decline in economic activity leading to a fall in GDP for two or more consecutive quarters (i.e. six months). The Great Recession can be defined as the recession that started in December 2007 within the US economic system and subsequently spread to the rest of the world.

The expression ‘socially valuable resources’ is employed here as a placeholder that is meant to encompass all currencies of distributive justice.

Real income can be defined as nominal income adjusted for inflation.

Some may object that at least one of the factors I have cited above can be considered a long-term explanation, in that the global savings glut can be seen as the result of a long-term shift in economic power from West to East (see Ross 2010). Be that as it may, the explanation remains unconvincing. Given that many Western economies could access capital more cheaply because of the so-called savings glut, it seems an unhelpful way of differentiating the US from other countries (see Roemer 2012).

The data is from Wisman (2013). The other quintiles have witnessed the following income growth: second quintile, 15.8 per cent; middle quintile, 21 per cent; fourth quintile, 29.5 per cent.

I borrow this expression from Scheffler (2015), p. 25.

Positional goods are goods ‘the absolute value of which, to their possessors, depends on those possessors’ place in the distribution of the good—on their relative standing with respect to the good in question’: Brighouse and Swift (2006), p. 474.

And some would point out, even irrational: see Morgan-Knapp (2014).

Here I follow Freye (2016).

Or alternatively, the elimination of the effects on life prospects of positional goods.

I would like to thank one of the reviewers for pressing me on this point.

Regulatory capture refers to the relationship between private agents and their regulators. It can be dictated by several mechanisms such as: (a) political campaign financing; (b) ex-ante revolving doors (moving from a private sector post to the sector’s regulatory agency); (c) ex-post revolving doors (moving from a regulator to a private sector agent regulated by it); and (d) epistemic dependence (private firms acting as the primary source of information for the regulator). See Dal Bó (2006).

For a discussion of the moral aspects of the Pareto criterion see Hausman and McPherson (2006).

The general thread of the argument follows from Jubb (2015).

References

Acharya, Viral V., et al. 2011. Guaranteed to fail: Fannie Mae, Freddie Mac, and the debacle of mortgage finance. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Anderson, Elizabeth. 1999. What is the point of equality? Ethics 109: 287–337.

Atkinson, A. B., and Salvatore Morelli. 2011. Economic crises and inequality. UNDP Human Development Research Paper 2011/06. http://hdr.undp.org/sites/default/files/hdrp_2011_06.pdf. Accessed April 2014.

Bartels, Larry M. 2008. Unequal democracy: The political economy of the new gilded age. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Bazillier, Rémi, and Jérôme Héricourt. 2014. The circular relationship between inequality, leverage, and financial crises: Intertwined mechanisms and competing evidence. CEPII Working Paper 2014–22. http://cepii.fr/PDF_PUB/wp/2014/wp2014-22.pdf. Accessed April 2015.

Beitz, Charles R. 2001. Does global inequality matter? Metaphilosophy 32: 95–112.

Bitner, Richard. 2008. Confessions of a subprime lender: An insider’s tale of greed, fraud and ignorance. New York, NY: Wiley.

Brighouse, Harry, and Adam Swift. 2006. Equality, priority, and positional goods. Ethics 116: 471–497.

Buchanan, Allen. 1985. Ethics, efficiency, and the market. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

Canova, Timothy A. 2009. Financial market failure as a crisis in the rule of law: From market fundamentalism to a new Keynesian regulatory model. NSUWorks. http://nsuworks.nova.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1020&context=law_facarticles. Accessed April 2014.

Christiano, Thomas. 2012. Money in politics. In The Oxford handbook of political philosophy, ed. David Estlund, 241–257. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Claassen, Rutger. 2014. The status struggle: A recognition-based interpretation of the positional economy. Philosophy and Social Criticism 34: 1021–1049.

Cohen, Joshua. 2009. Philosophy, politics, democracy: Selected essays. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Dal Bó, Ernesto. 2006. Regulatory capture: A review. Oxford Review of Economic Policy 22: 203–225.

Davies, Howard. 2010. The financial crisis: Who is to blame?. Cambridge: Polity Press.

Dobos, Ned, Christian Barry, and Thomas Pogge (eds.). 2011. Global financial crisis: The ethical issues. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

Dworkin, Ronald. 1983. Comment on Narveson: In defense of equality. Social Philosophy and Policy 1: 24–40.

Eberle, Christopher. 2002. Religious conviction in liberal politics. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Federal Reserve Bank of New York. 2013. Quarterly report on household debt and credit.

Fitoussi, Jean-Paul, and Francesco Saraceno. 2010. Inequality and macroeconomic performance. OFCE/Sciences Po 2010-13. https://www.ofce.sciences-po.fr/pdf/dtravail/WP2010-13.pdf. Accessed April 2014.

Franck, Robert H. 2013. Falling behind: How rising inequality harms the middle class. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press.

Frank, Thomas H. 2010. Luxury fever: Weighing the costs of excess. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Freye, Harrison. 2016. The relation of envy to distributive justice. Social Theory and Practice 42: 501–524.

Froud, Julie, et al. 2010. Escaping the tyranny of earned income? The failure of finance as social innovation. New Political Economy 15: 147–164.

Galbraith, James K. 2012. Inequality and instability: A study of the world economy just before the great crisis. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Gauthier, 1987. Morals by agreement. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Hager, Sandy Brian. 2014. What happened to the bondholding class? Public debt, power and the top 1%. New Political Economy 19: 155–182.

Hausman, Daniel M., and Michael S. McPherson. 2006. Economic analysis, moral philosophy, and public policy. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Heath, Joseph. 2006. Envy and efficiency. Revue de Philosophie Economique 14: 1–27.

Hirsch, Fred. 1995 [1976]. Social limits to growth, rev. edn. London: Routledge.

Holt, Richard P. F., and Daphne T. Greenwood. 2012. Negative trickle-down and the financial crisis of 2008. Journal of Economic Issues 46: 363–370.

Horton, John. 2010. Realism, liberal moralism, and a political theory of modus vivendi. European Journal of Political Theory 9: 431–448.

James, Aaron. 2012. Fairness in practice: A social contract for a global economy. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Jickling, Mark. 2009. Causes of the financial crisis. Cornell University ILR School. http://digitalcommons.ilr.cornell.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1605&context=key_workplace. Accessed March 2014.

Johnson, Simon, and James Kwak. 2010. 13 bankers: The Wall Street takeover and the next financial meltdown. New York, NY: Pantheon Books.

Jubb, Robert. 2015. The real value of equality. Journal of Politics 77: 679–691.

Kindleberger, Charles P., and Robert Z. Aliber. 1986 [1978]. Manias, panics and crashes: A history of financial crises, 5th edn. Hoboken, NJ: Wiley.

Kumhof, Michael et al. 2012. Income inequality and current account imbalances. IMF Working Paper WP/12/08. https://www.imf.org/external/pubs/ft/wp/2012/wp1208.pdf. Accessed May 2014.

Kwak, James. 2014. Cultural capture and the financial crisis. In Preventing regulatory capture: Special interest influence and how to limit it, ed. Daniel Carpenter, and David A. Moss. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Le Grand, Julian. 1990. Equity versus efficiency: The elusive trade-off. Ethics 100: 554–568.

Lichtenberg, Judith. 1996. Consuming because others consume. Social Theory and Practice 22: 273–297.

Lo, Andrew W. 2012. Reading about the financial crisis: A 21-book review. Journal of Economic Literature 50: 151–178.

Lomasky, Loren E. 2011. Liberty after Lehman brothers. Social Philosophy and Policy 18: 135–165.

Lysandrou, Photis. 2011. Global inequality as one of the root causes of the financial crisis: A suggested explanation. Economy and Society 40: 323–344.

Maestri, Virginia, and Andrea Roventini. 2012. Inequality and macroeconomic factors: A time-series analysis for a set of OECD countries. https://ssrn.com/abstract=2181399. Accessed June 2014.

Milanovic, Branko. 2009. Income inequality and speculative investment by the rich and poor in America led to the financial meltdown. YaleGlobal Online. http://yaleglobal.yale.edu/content/two-views-global-crisis. Accessed May 2014.

Minsky, Hyman P. 1986. Stabilizing an unstable economy, 144. Minsky Archive, Paper: Hyman P.

Morgan-Knapp, Christopher. 2014. Economic envy. Journal of Applied Philosophy 31: 113–126.

Morris, Charles R. 2008. The trillion dollar meltdown: Easy money, high rollers, and the great credit crash. New York, NY: Public Affairs.

Muolo, Paul, and Mathew Padilla. 2010. Chain of blame: How Wall Street caused the mortgage and credit crisis. New York, NY: Wiley.

Okun, Arthur M. 1975. Equality and efficiency: The big tradeoff. Washington, DC: Brookings Institution Press.

O’Neill, Martin. 2008. What should egalitarians believe? Philosophy & Public Affairs 36: 119–156.

O’Neill, Martin. 2010. The facts of inequality. Journal of Moral Philosophy 7: 397–409.

Perugini, Cristiano, Jens Hölscher and Simon Collie. 2013. Inequality, credit expansion and financial crises. MPRA Paper No. 51336. https://mpra.ub.uni-muenchen.de/51336/1/MPRA_paper_51336.pdf. Accessed September 2014.

Piketty, Thomas. 2014. Capital in the 21st century. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Piketty, Thomas, and Emmanuel Saez. 2003. Income inequality in the United States, 1913–1998. Quarterly Journal of Economics 118: 1–40.

Posner, Richard. 2009. A failure of capitalism: The crisis of ’08 and the descent into depression. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Rajan, Raghuram G. 2010. Fault lines: How hidden fractures still threaten the world economy. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Rawls, John. 1971. A theory of justice. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Rawls, John. 1996. Political liberalism, rev ed. New York, NY: Columbia University Press.

Rawls, John. 1999 [1971]. A theory of justice, rev. edn. Cambridge, MA: Belknap Press of Harvard University.

Rawls, John. 2001. Justice as fairness: A restatement. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Reinhart, Carmen M., and Kenneth S. Rogoff. 2009. The aftermath of financial crises. American Economic Review 99: 466–472.

Roemer, John E. 2012. Ideology, social ethos, and the financial crisis. Journal of Ethics 16: 273–303.

Ross, Don. 2010. Should the financial crisis inspire normative revision? Journal of Economic Methodology 17: 399–418.

Rossi, Enzo, and Matt Sleat. 2014. Realism in normative political theory. Philosophy Compass 9: 689–701.

Roubini, Nouriel, and Stephen Mihm. 2010. Crisis economics: A crash course in the future of finance. New York: Penguin.

Saez, Emmanuel. 2013. Striking it richer: The evolution of top incomes in the United States. http://eml.berkeley.edu//~saez/saez-UStopincomes-2012.pdf. Accessed October 2014.

Scanlon, T. M. 2003. The difficulty of tolerance: Essays in political philosophy. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Scheffler, Samuel. 2015. The practice of equality. In Social equality: Essays on what it means to be equals, ed. Carina Fourie, Fabian Schuppert, and Ivo Wallimann-Helmer, 21–44. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Schor, Juliet B. 1998. The overspent American: Why we want what we don’t need. New York, NY: HarperCollins.

Sen, Amartya. 2009. The idea of justice. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Shiller, Robert J. 2008. The subprime solution: How today’s global financial crisis happened and what to do about it. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Stemplowska, Zofia, and Adam Swift. 2012. Ideal and Nonideal Theory. In The Oxford handbook of political philosophy, ed. David Estlund, 373–390. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Stiglitz, Joseph. 2012. The price of inequality. New York, NY: Allen Lane.

Stockhammer, Engelbert. 2012. Rising inequality as a root cause of the present crisis. http://cje.oxfordjournals.org/content/early/2013/11/25/cje.bet052. Accessed March 2014.

Tett, Gillian. 2009. Fool’s gold: How unrestrained greed corrupted a dream, shattered global markets and unleashed a catastrophe. London: Abacus.

Tomlin, Patrick. 2008. Envy, facts and justice: A critique of the treatment of envy in justice as fairness. Res Publica 14: 101–116.

Valentini, Laura. 2012. Ideal versus non-ideal theory: A conceptual map. Philosophy Compass 7: 654–664.

Van Treeck, Till. 2014. Did inequality cause the U.S. financial crisis? Journal of Economic Surveys 28: 421–448.

Warren, Elizabeth. 2003. The two-income trap: Why middle-class mothers and fathers are going broke. New York, NY: Basic Books.

White, Stuart. 2007. Equality. Cambridge: Polity Press.

Wilkinson, Richard, and Kate Pickett. 2009. The spirit level: Why equality is better for everyone. London: Bloomsbury.

Wisman, Jon D. 2013. Wage stagnation, rising inequality and the financial crisis of 2008. Cambridge Journal of Economics 37: 921–945.

Wolff, Edward N. 2010. Recent trends in household wealth in the United States: Rising debt and the middle-class squeeze—an update to 2007. Levy Economic Institute Working Paper 589 (2010). http://www.levyinstitute.org/pubs/wp_589.pdf. Accessed Oct 2014.

Wolff, Jonathan. 2015. Social equality and social inequality. In Social equality: Essays on what it means to be equals, ed. Carina Fourie, Fabian Schuppert, and Ivo Wallimann-Helmer, 209–225. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

I would like to thank Julian Reiss, Ed Hall, Rutger Claassen, Boudewijn de Bruin, Marco Meyer, and Or Raviv, for comments at different stages of the writing process. I would also like to thank the anonymous referees for their very detailed comments on the first submitted version of the paper.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Maffettone, P. Egalitarianism and the Great Recession: A Tale of Missed Connections?. Res Publica 24, 237–256 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11158-016-9349-7

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11158-016-9349-7