Abstract

This study develops a theory that predicts the lower the degree to which firms’ earnings are correlated with the industry the greater the probability a firm will issue a biased signal of firm performance. The theory provides for causal predictions in our empirical tests in which we examine the probability a firm will be subject to an Accounting and Auditing Enforcement Release (AAER). The empirical findings provide support for the theory, even after controlling for various predictive variables from the literature, indicating the degree of earnings co-movements with the industry is in fact a causal factor in managers decisions to bias earnings reports. We further illustrate that low co-movement firms are less conservative than high co-movement firms, which provides an application of our theory to a broader setting. Overall, we provide both a theory and an empirical validation of the theory helping to discipline the thinking about earnings management and allowing for causal relations to be uncovered.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

Many of these models also incorporate the notion that the market identifies the bias and will price protect accordingly as long as investors are rational and have perfect common knowledge of the manager’s reporting objectives. When these assumptions are relaxed, reporting biases can influence prices in equilibrium (Fischer and Verrecchia 2000).

In essence, \(\tilde {e}\) and \(\tilde {e}\) are bivariate Normal with the mean vector μ and the variance covariance matrix Σ given by

$$\mu =\left[ \begin{array}{c} 0 \\ 0 \end{array}\right] ,\text{ }{\Sigma} =\left[ \begin{array}{ll} \sigma^{2} & \,\rho \sigma \sigma_{E} \\ \rho \sigma \sigma_{E} & \,{\sigma_{E}^{2}} \end{array} \right] . $$Note that β = ρσ/σ E .

We will assume that there is always a firm-specific risk component i.e., \( {\sigma _{u}^{2}}>0\), which implictly places an upper bound on the extent of co-movement β i.e., \(\beta <\bar {\beta }=\sigma /\sigma _{E}\).

Theoretically, R 2 ≈ 1 −\({\sigma _{u}^{2}}/\sigma ^{2}\) \(\equiv \beta ^{2}{\sigma _{E}^{2}}/\sigma ^{2}\).

Inferences are unchanged if we use market level earnings instead of and in addition to industry level earnings. We elect to use industry level co-movements since firms are typically evaluated on an industry basis rather than versus the entire market.

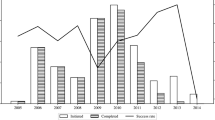

The sample is restricted to this period because of the need for AAER data obtained from Dechow et al. (2011) for our primary tests. We conduct sub-period analyses as robustness tests to ensure the results are consistent over time and there is nothing systematically biasing the results by using the entire sample period in the reported tables.

The larger percentage of AAERs in our sample is a function of the construction of co-movements, which requires significant time-series to calculate. Given the SEC tends to prosecute more high profile cases of earnings management, AAER firms tend to be maintained in our sample, whereas smaller non-AAER firms are eliminated because of variable construction leaving a larger percentage of AAERs.

To ensure that the partitions capture different aspects of the information environment, we correlated the indicator variables used to create the partitions for each variable. In untabulated findings, the highest correlation in terms of magnitude is 0.07 between age and analyst coverage indicating that the variables are capturing quite different aspects of firms’ environments.

The literature has identified problems with the HHI as a measure of competition, including the lack of inclusion of private firms, staleness of codes, and potential endogeneity concerns. See, for example, Karuna (2007), Ali et al. (2014), and Hoberg and Phillips (2010). We elect to use the HHI since it corresponds well to our industry definitions and is available for the entire sample period. Many of the new competition measures are only available since the mid-1990s or for a subset of industries. Furthermore, a number of studies cited concerning the countervailing forces of competition use the HHI, including Aggarwal and Samwick (1999) and Balakrishnan and Cohen (2012), indicating it best aligns with the referenced literature.

Execucomp excludes many of the sample firms, and we do not have access to broader databases like Equilar.

We do note that the coefficient on Ret in both samples is negative, which differs from the results presented in Basu (1997), but is consistent with a number of more recent studies investigating conservatism (see Martin and Rowchowdhury2015 and Banker et al. 2016, among others). In untabulated analysis, we document a similar positive coefficient to Basu (1997) if we limit the sample to the years in Basu (1997) with no change to the inferences on the co-movement subsamples.

The sentiment beta proposed by Glushkov (2006) is essentially the Carhart four-factor model including a sentiment factor from Baker and Wurgler (2006) estimated over rolling 60-month periods, with the coefficient on the sentiment factor capturing how sensitive a firm’s returns are to market wide sentiment (Coulton et al. 2016).

References

Aggarwal, R.K., & Samwick, A.A. (1999). Executive compensation, strategic competition, and relative performance evaluation: Theory and evidence. The Journal of Finance, 54, 1999–2043.

Ahmed, A.S., & Duellman, S. (2007). Accounting conservatism and board of director characteristics: An empirical analysis. Journal of Accounting and Economics, 43, 411–437.

Ali, A., Klasa, S., & Yeung, E. (2014). Industry competition and corporate disclosure policy. Journal of Accounting and Economics, 58, 240–264.

Ang, A., Chen, J., & Xing, Y. (2006). Downside risk. Review of Financial Studies, 19, 1191–1239.

Baker, M., & Wurgler, J. (2006). Investor sentiment and the cross-section of stock returns. The Journal of Finance, 61, 1645–1680.

Balakrishnan, K., & Cohen, D.A. (2012). Product market competition and financial accounting misreporting. Working paper, University of Pennsylvania.

Ball, R. (2013). Accounting informs investors and earnings management is rife: Two questionable beliefs. Accounting Horizons, 27, 847–853.

Banker, R.D., Basu, S., Byzalov, D., & Chen, J.Y.S. (2016). The confounding effect of cost stickiness on conservatism estimates. Journal of Accounting and Economics, 61, 203–220.

Basu, S. (1997). The conservatism principle and the asymmetric timeliness of earnings. Journal of Accounting and Economics, 24, 3–37.

Beaver, W., Kettler, P., & Scholes, M. (1970). The association between market determined and accounting determined risk measures. The Accounting Review, 45, 654–682.

Beyer, A. (2009). Capital market prices, management forecasts, and earnings management. The Accounting Review, 84, 1713–1747.

Beyer, A., Cohen, D.A., Lys, T.Z., & Walther, B.R. (2010). The financial reporting environment: Review of the recent literature. Journal of Accounting and Economics, 50, 296–343.

Beyer, A., Guttman, I., & Marinovic, I. (2014). Earnings management and earnings quality Theory and evidence. Working paper, Stanford University.

Bradshaw, M., Richardson, S., & Sloan, R. (2006). The relation between corporate financing activities, analysts’ forecasts, and stock returns. Journal of Accounting and Economics, 42, 53–85.

Brennan, M., & Subrahmanyam, A. (1995). Investment analysis and price formation in securities markets. Journal of Financial Economics, 38, 361–381.

Brown, N., & Kimbrough, M.D. (2011). Intangible investment and the importance of firm-specific factors in the determination of earnings. Review of Accounting Studies, 16, 539–573.

Coulton, J.J., Dinh, T., & Jackson, A.B. (2016). The impact of sentiment on price discovery. Accounting & Finance, 56, 669–694.

Cunat, V., & Guadalupe, M. (2005). How does product market competition shapre incentive contracts? Journal of the European Economic Association, 3, 1058–1082.

De Angelis, D., & Grinstein, Y. (2015). Perfromance terms in CEO compensation contracts. Review of Finance, 19, 619–651.

De Franco, G., Kothari, S. P., & Verdi, R. S. (2011). The benefits of financial statement comparability. Journal of Accounting Research, 49, 895–931.

Dechow, P., Ge, W., & Schrand, C. (2010). Understanding earnings quality: a review of the proxies, their determinants and their consequences. Journal of Accounting and Economics, 50, 344– 401.

Dechow, P.M., Ge, W., Larson, C.R., & Sloan, R.G. (2011). Predicting material accounting misstatements. Contemporary Accounting Research, 28, 17–82.

Dye, R.A., & Sridhar, S.S. (2004). Reliability-relevance trade-offs and the efficiency of aggregation. Journal of Accounting Research, 42, 51–88.

Fama, E.F. (1980). Agency problems and the theory of the firm. Journal of Political Economy, 88, 288–307.

Fink, J., Fink, K.E., Grullon, G., & Weston, J.P. (2010). What drove the increase in idiosyncratic volatility during the internet boom. Journal of Financial and Quantitative Analysis, 45, 1253–1278.

Fischer, P.E., & Verrecchia, R.E. (2000). Reporting bias. The Accounting Review, 75, 229–245.

Forsyth, J., Teoh, S.H., & Zhang, Y. (2007). Misvaluation, CEO equity-based compensation and corporate governance. Working paper, Pepperdine University.

Francis, J., LaFond, R., Olsson, P.M., & Schipper, K. (2004). Costs of equity and earnings attributes. The Accounting Review, 79, 967–1010.

Gerakos, J., & Kovrijnykh, A. (2013). Performance shocks and misreporting. Journal of Accounting and Economics, 56, 57–72.

Giroud, X., & Mueller, H.M. (2010). Does corporate governance matter in competitive industries? Journal of Financial Economics, 95, 312–331.

Graham, J., Harvey, C., & Rajgopal, S. (2005). The economic implications of corporate financial reporting. Journal of Accounting and Economics, 40, 3–73.

Glushkov, D. (2006). Sentiment beta. Working paper, University of Pennsylvania.

Gong, G., Li, L.Y., & Zhou, L. (2013). Earnings non-synchronicity and voluntary disclosure. Contemporary Accounting Research, 30, 1560–4589.

Heinle, M.S., & Verrecchia, R.E. (2016). Bias and the commitment to disclosure. Management Science, 62, 2859–2870.

Hoberg, G., & Phillips, G. (2010). Real and financial industy booms and busts. The Journal of Finance, 65, 45–86.

Hong, H., Lim, T., & Stein, J. (2000). Bad news travels slowly: size, analyst coverage, and the profitability of momentum strategies. The Journal of Finance, 55, 265–295.

Ittner, C.D., Lambert, R.A., & Larcker, D.F. (2003). The structure and performance consequences of equity grants to employees of new economy firms. Journal of Accounting and Economics, 34, 89–127.

Karuna, C. (2007). Industry product market competition and managerial incentives. Journal of Accounting and Economics, 43, 275–297.

LaFond, R., & Watts, R. (2008). The information role of conservatism. The Accounting Review, 83, 447–478.

Martin, X., & Rowchowdhury, S. (2015). Do financial market developments influence accounting practices? Credit default swaps and borrowers reporting conservatism. Journal of Accounting and Economics, 59, 80–104.

Richardson, S.A., Sloan, R.G., Soliman, M.T., & Tuna, I. (2005). Accrual reliability, earnings persistence and stock prices. Journal of Accounting and Economics, 39, 437–485.

Shleifer, A., & Vishny, R.W. (1997). A survey of corporate governance. The Journal of Finance, 52, 737–783.

Strobl, G. (2013). Earnings management and the cost of capital. Journal of Accounting Research, 51, 449–473.

Watts, R.L. (2003). Conservatism in accounting Part I: Explanations and implications. Accounting Horizons, 17, 207–221.

Yu, F. (2008). Analyst coverage and earnings management. Journal of Financial Economics, 88, 245–271.

Zakolyukina, A.A. (2014). Measure of intentional manipulation: a structural approach. Working paper, University of Chicago.

Acknowledgements

We gratefully acknowledge comments from two anonymous reviewers, Jeremy Bertomeu, Philip Brown, Greg Clinch, Asher Curtis, Peter Easton (editor), Weili Ge, Phil Quinn, Phil Stocken, Gunter Strobl, Dan Taylor, Steve Taylor, Irene Tuttici, Terry Walter, Anne Wyatt, Teri Yohn, and seminar participants at University of Melbourne, University of Otago, Rice University, UNSW Australia, University of Queensland, and Victoria University of Wellington, 2013 AAA Annual Conference, 2014 AAA FARS Section Meeting, 2014 AFAANZ Annual Conference, and 2014 University of Technology Sydney Summer Research Symposium. All errors remain our own responsibility. This paper was previously titled “Sentiment, Earnings Co-Movements and Earnings Manipulation.”

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Appendix 1: Proof of Proposition 1

Appendix 1: Proof of Proposition 1

Proof

Note that

With \(\lambda _{x}=\frac {\alpha _{r}}{c},\)

The optimal reporting bias is given by Eq. 5:

Our interestis to sign \(\frac {db(x,s)}{d\beta }:\)

Differentiating Eq. 9with respect to β,

Notingthat \(\sigma ^{2}-\beta ^{2}{\sigma _{E}^{2}}={\sigma _{u}^{2}}>0\)(where \({\sigma _{u}^{2}}\),the firm-specific risk component is always positive by assumption—see footnote 3), the coefficient of d α r /d β is positive.With 0 < α r < 1,the term\(2\beta \sigma ^{2}\left (1-\alpha _{r}\right ) \)is positive if β > 0, and it mustbe that \(\frac { d\alpha _{r}}{d\beta }<0\), whichyields \(\frac {db(x,s)}{d\beta }<0\). The term\(2\beta \sigma ^{2}\left (1-\alpha _{r}\right ) \)is negative if β < 0, in which case it mustbe that \(\frac {d\alpha _{r}}{d\beta }>0\), which yields\(\frac {db(x,s)}{d\beta }>0\). Combining these twoeffects, it can be seen that \(\frac {d\alpha _{r}}{d\left \vert \beta \right \vert }<0\),and therefore \(\frac {db(x,s)}{d\left \vert \beta \right \vert }<0\),i.e., the reporting bias is decreasing in the magnitude of the earnings co-movement. It can also be seenthat \(\frac {d\alpha _{r}}{d{\sigma _{u}^{2}}} >0\)and \(\frac {db(x,s)}{d{\sigma _{u}^{2}}}>0\). □

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Jackson, A.B., Rountree, B.R. & Sivaramakrishnan, K. Earnings co-movements and earnings manipulation. Rev Account Stud 22, 1340–1365 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11142-017-9411-5

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11142-017-9411-5

Keywords

- Accounting and auditing enforcement releases

- Accounting theory

- Earnings co-movements

- Earnings management

- Market earnings