Abstract

Objective

Develop efficient and accurate screening tools to identify elevated levels of depressive or somatization symptoms, which can adversely affect functional status outcomes.

Methods

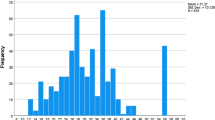

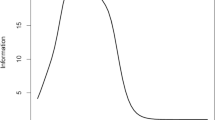

We conducted a secondary analysis of prospectively collected depressive and somatization symptoms (Symptom Checklist 90-Revised) data from 10,920 patients receiving outpatient physical therapy for a variety of neuromusculoskeletal diagnoses. Item response theory methods were used to analyze data, with particular emphasis on differential item functioning among groups of patients, and to identify potential screening items. Screening item accuracy for identifying patients with elevated symptoms was assessed with receiver-operating characteristic analyses.

Results

Seven items for depressive and 10 items for somatization symptoms represented unidimensional scales. Differential item functioning was negligible for demographic and clinical variables known to affect functional status outcomes. Items providing maximum information at the 88th percentile for depressive and 77th percentile for somatization scales accurately dichotomized patients into elevated versus not elevated symptom levels.

Conclusions

Lack of differential item functioning suggested depressive and somatization screening could be useful in routine clinical practice and allowed the development of single-item screens that accurately identified patients with elevated depressive or somatization symptoms. Item response theory-based single-item screens may facilitate evaluation and management of heterogeneous populations receiving outpatient physical therapy.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Dionne, C. E., Le Sage, N., Franche, R. L., Dorval, M., Bombardier, C., & Deyo, R. A. (2011). Five questions predicted long-term, severe, back-related functional limitations: Evidence from three large prospective studies. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology, 64(1), 54–66.

Pincus, T., Burton, A. K., Vogel, S., & Field, A. P. (2002). A systematic review of psychological factors as predictors of chronicity/disability in prospective cohorts of low back pain. Spine, 27(5), E109–E120.

Deutscher, D., Horn, S. D., Dickstein, R., Hart, D. L., Smout, R. J., Gutvirtz, M., et al. (2009). Associations between treatment processes, patient characteristics, and outcomes in outpatient physical therapy practice. Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation, 90, 1349–1363.

Haggman, S., Maher, C. G., & Refshauge, K. M. (2004). Screening for symptoms of depression by physical therapists managing low back pain. Physical Therapy, 84(12), 1157–1166.

Mannion AF, Junge A, Taimela S, Muntener M, Lorenzo K, Dvorak J. Active therapy for chronic low back pain: part 3. Factors influencing self-rated disability and its change following therapy. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2001 Apr 15;26(8):920–929.

Hart, D. L., Werneke, M. W., George, S. Z., Matheson, J. W., Wang, Y. C., Cook, K. F., et al. (2009). Screening for elevated levels of fear-avoidance beliefs regarding work or physical activities in people receiving outpatient therapy. Physical Therapy, 89(8), 770–785.

Bair, M. J., Robinson, R. L., Katon, W., & Kroenke, K. (2003). Depression and pain comorbidity: A literature review. Archives of Internal Medicine, 163(20), 2433–2445.

McWilliams, L. A., Cox, B. J., & Enns, M. W. (2003). Mood and anxiety disorders associated with chronic pain: An examination in a nationally representative sample. Pain, 106(1–2), 127–133.

Hilty, D. M., Bourgeois, J. A., Chang, C. H., & Servis, M. E. (2001). Somatization disorder. Current Treatment Options in Neurology, 3(4), 305–320.

Allen, L. A., Woolfolk, R. L., Escobar, J. I., Gara, M. A., & Hamer, R. M. (2006). Cognitive-behavioral therapy for somatization disorder: A randomized controlled trial. Archives of Internal Medicine, 166(14), 1512–1518.

Janca, A., Isaac, M., & Ventouras, J. (2006). Towards better understanding and management of somatoform disorders. International Review of Psychiatry, 18(1), 5–12.

Dionne, C. E. (2005). Psychological distress confirmed as predictor of long-term back-related functional limitations in primary care settings. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology, 58(7), 714–718.

Dionne, C. E., Koepsell, T. D., Von Korff, M., Deyo, R. A., Barlow, W. E., & Checkoway, H. (1997). Predicting long-term functional limitations among back pain patients in primary care settings. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology, 50(1), 31–43.

Derogatis, L. R., & Melisaratos, N. (1983). The Brief Symptom Inventory: An introductory report. Psychological Medicine, 13(3), 595–605.

Derogatis, L. R., Lipman, R. S., & Covi, L. (1973). SCL-90: An outpatient psychiatric rating scale–preliminary report. Psychopharmacology Bulletin, 9(1), 13–28.

Deutscher, D., Hart, D. L., Dickstein, R., Horn, S. D., & Gutvirtz, M. (2008). Implementing an integrated electronic outcomes and electronic health record process to create a foundation for clinical practice improvement. Physical Therapy, 88(2), 270–285.

van der Linden, W., & Hambleton, R. K. (Eds.). (1997). Handbook of modern item response theory. New York, NY: Springer.

DeSalvo, K. B., Fisher, W. P., Tran, K., Bloser, N., Merrill, W., & Peabody, J. (2006). Assessing measurement properties of two single-item general health measures. Quality of Life Research, 15(2), 191–201.

Millsap, R. E., & Everson, H. T. (1993). Methodology review: Statistical approaches for assessing measurement bias. Applied Psychological Measurement, 17, 287–334.

Lord, F. M. (1980). Applications of item response theory to practical testing problems. Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Swinkels, I. C., Hart, D. L., Deutscher, D., van den Bosch, W. J., Dekker, J., de Bakker, D. H., et al. (2008). Comparing patient characteristics and treatment processes in patients receiving physical therapy in the United States, Israel and the Netherlands. Cross sectional analyses of data from three clinical databases. BMC Health Services Research, 8(1), 163.

Hart, D. L., Wang, Y. C., Stratford, P. W., & Mioduski, J. E. (2008). Computerized adaptive test for patients with knee impairments produced valid and responsive measures of function. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology, 61(11), 1113–1124.

Hart, D. L., Wang, Y. C., Stratford, P. W., & Mioduski, J. E. (2008). Computerized adaptive test for patients with foot or ankle impairments produced valid and responsive measures of function. Quality of Life Research, 17(8), 1081–1091.

Hart, D. L., Werneke, M. W., Wang, Y. C., Stratford, P. W., & Mioduski, J. E. (2010). Computerized adaptive test for patients with lumbar spine impairments produced valid and responsive measures of function. Spine, 35(24), 2157–2164.

Rossignol, M., Arsenault, B., Dionne, C. E., Poitras, S., Tousignant, M., & Truchon, M., et al. (2006). Clinic on Low-Back Pain in Interdisciplinary Practice (CLIP) Guidelines. In MPH Do (Ed.), Montreal, Canada: Agence de la sante et de services sociaux de Montreal.

Derogatis, L. R., Rickels, K., & Rock, A. F. (1976). The SCL-90 and the MMPI: A step in the validation of a new self-report scale. British Journal of Psychiatry, 128, 280–289.

Hyphantis, T., Tomenson, B., Paika, V., Almyroudi, A., Pappa, C., Tsifetaki, N., et al. (2009). Somatization is associated with physical health-related quality of life independent of anxiety and depression in cancer, glaucoma and rheumatological disorders. Quality of Life Research, 18(8), 1029–1042.

Von Korff, M., Le Resche, L., & Dworkin, S. F. (1993). First onset of common pain symptoms: A prospective study of depression as a risk factor. Pain, 55(2), 251–258.

Bernstein, I. H., Jaremko, M. E., & Hinkley, B. S. (1994). On the utility of the SCL-90-R with low-back pain patients. Spine (Phila Pa 1976), 19(1), 42–48.

Cassisi, J. E., Sypert, G. W., Lagana, L., Friedman, E. M., & Robinson, M. E. (1993). Pain, disability, and psychological functioning in chronic low back pain subgroups: Myofascial versus herniated disc syndrome. Neurosurgery, 33(3), 379–385. (discussion 85–86).

Hambleton, R. K., Swaminathan, H., & Rogers, H. J. (1991). Fundamentals of item response theory. Newbury Park, CA: Sage.

Hays, R. D., Morales, L. S., & Reise, S. P. (2000). Item response theory and health outcomes measurement in the 21st century. Medical Care, 38(9 Suppl), II28–II42.

Muthén, L. K., & Muthén, B. O. (2006). Mplus user’s guide (4th ed.). Los Angeles, CA: Muthén & Muthén.

Bjorner, J. B., Kosinski, M., & Ware, J. E., Jr. (2003). The feasibility of applying item response theory to measures of migraine impact: A re-analysis of three clinical studies. Quality of Life Research, 12(8), 887–902.

Fliege, H., Becker, J., Walter, O. B., Bjorner, J. B., Klapp, B. F., & Rose, M. (2005). Development of a computer-adaptive test for depression (D-CAT). Quality of Life Research, 14(10), 2277–2291.

Hu, L. T., & Bentler, P. (1999). Cutoff criteria for fit indices in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling, 6, 1–55.

Tucker, L., & Lewis, C. (1973). A reliability coefficient for maximum likelihood factor analysis. Psychometrika, 38, 1–10.

Browne, M. W., & Cudeck, R. (1993). Alternative ways of assessing model fit. In K. A. Bollen & J. A. Long (Eds.), Testing structural equation models. Newbury Park, CA: Sage Publications.

Cook, K. F., Kallen, M. A., & Amtmann, D. (2009). Having a fit: Impact of number of items and distribution of data on traditional criteria for assessing IRT’s unidimensionality assumption. Quality of Life Research, 18(4), 447–460.

Samejima, F. (1969). Estimation of ability using a response pattern of graded responses. Psycometrika. Monograph 17.

PARSCALE for Windows. v 4.1. Lincolnwood, IL: Scientific Software International.; 2003.

Dodd, B. G., Koch, W. R., & De Ayala, R. J. (1989). Operational characteristics of adaptive testing procedures using the Graded Response Model. Applied Psychological Measurement, 13(2), 129–143.

Thissen, D. (2000). Reliability and measurement precision. In H. Wainer (Ed.), Computerized adaptive testing a primer (2nd ed., pp. 159–184). Wahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Rose, M., Bjorner, J. B., Becker, J., Fries, J. F., & Ware, J. E. (2008). Evaluation of a preliminary physical function item bank supported the expected advantages of the Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System (PROMIS). Journal of Clinical Epidemiology, 61(1), 17–33.

Crane, P. K., Gibbons, L. E., Jolley, L., & van Belle, G. (2006). Differential item functioning analysis with ordinal logistic regression techniques. DIFdetect and difwithpar. Medical Care, 44(11 Suppl 3), S115–S123.

Deutscher, D., Hart, D. L., Crane, P. K., & Dickstein, R. (2010). Cross cultural differences in knee functional status outcomes in a polyglot society represented true disparities not biased by differential item functioning. Physical Therapy, 11(3), 288–303.

Hart, D. L., Deutscher, D., Crane, P. K., & Wang, Y. C. (2009). Differential item functioning was negligible in an adaptive test of functional status for patients with knee impairments who spoke English or Hebrew. Quality of Life Research, 18(8), 1067–1083.

Delitto, A., Erhard, R. E., & Bowling, R. W. (1995). A treatment-based classification approach to low back syndrome: Identifying and staging patients for conservative treatment. Physical Therapy, 75(6), 470–489.

Crane, P. K., Gibbons, L. E., Ocepek-Welikson, K., Cook, K., Cella, D., Narasimhalu, K., et al. (2007). A comparison of three sets of criteria for determining the presence of differential item functioning using ordinal logistic regression. Quality of Life Research, 16 Suppl 1, 69–84.

Stata Statistical Software: Release 9.2. College Station, TX2007.

Hanley, J. A., & McNeil, B. J. (1982). The meaning and use of the area under a receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve. Radiology, 143(1), 29–36.

Choi, B. C. (1998). Slopes of a receiver operating characteristic curve and likelihood ratios for a diagnostic test. American Journal of Epidemiology, 148(11), 1127–1132.

Sackett, D. L., Straus, S. E., Richardson, W. S., Rosenberg, W., & Haynes, R. B. (2000). Evidence-based medicine. How to practice and teach EBM (2nd ed.). New York, NY: Churchill Livingstone.

Dujardin, B., Van den Ende, J., Van Gompel, A., Unger, J. P., & Van der Stuyft, P. (1994). Likelihood ratios: A real improvement for clinical decision making? European Journal of Epidemiology, 10(1), 29–36.

Jaeschke, R., Guyatt, G., & Sackett, D. L. (1994). Users’ guides to the medical literature. III. How to use an article about a diagnostic test. A. Are the results of the study valid? Evidence-based medicine working group. JAMA, 271(5), 389–391.

George, S. Z., & Zeppieri, G. (2009). Physical therapy utilization of graded exposure for patients with low back pain. Journal of Orthopaedic and Sports Physical Therapy, 39(7), 496–505.

Werneke, M. W., & Hart, D. L. (2003). Discriminant validity and relative precision for classifying patients with nonspecific neck and back pain by anatomic pain patterns. Spine, 28(2), 161–166.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Hart, D.L., Werneke, M.W., George, S.Z. et al. Single-item screens identified patients with elevated levels of depressive and somatization symptoms in outpatient physical therapy. Qual Life Res 21, 257–268 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11136-011-9948-x

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11136-011-9948-x