Abstract

The article concerns the return of education in Italy, assessed through labour market participation and occupation of people born in the cohort 1954–1958. The changes in time are analysed in the years 1993–2009, that is since the transition from school to work has been definitely ended (35–40 age group) until before retirement (50–55 age group). We will show that the relationship between education and employment is rather complex, varies over time and space, and features significant gender-based differences. In terms of employability and occupation, the advantage of a high level of education is relatively greater for those who occupy a more disadvantaged position in the labour market (women and those who live in the least dynamic areas of Italy).

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

There is an entire branch of sociology related to social mobility studies, which analyses the relationship between education, occupation and position in the social stratification system. This, however, is a different perspective from the one referred to in this article, even in the case of studies in which class mobility intersects with career mobility (Blossfeld and Hofmeister 2006; Blossfeld et al. 2006. Regarding Italy, see Schizzerotto 2002). While economics generally applies the neoclassical model to educational choices, sociological studies focus on studying whether and to what extent education contributes to determining an individual’s position in the social structure.

The National Institute of Statistics.

The sample size has changed considerably over time, going from 801,000 individuals in 1993 to 807,000 in 2004, eventually dropping to 660,000 in 2009.

This is clearly a simplification. What the three theories have in common is an emphasis on the value of education for the purpose of sorting individuals into different jobs. In other respects, there are some significant differences between them. For example, the theory of signals considers the characteristics of the labour supply and gives education an informative value, in the sense that it signals an individual’s abilities, competences and skills. Instead, the theory of job competition refers to the labour demand and states that in certain situations (such as when few good jobs are available or there is high unemployment) high educational qualifications can increase a worker’s chances of being selected. Finally, the theory of credentialism states that there is an unequal distribution of resources and that this conditions the educational choices made by subjects. Furthermore, social class exerts power in controlling access to certain professions and favouring some groups.

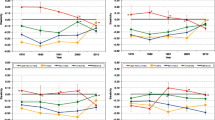

As income is not used as a dependent variable in this study, the option of applying the models of regression generally used in this type of research has been excluded. Another reason not to use them is that it would have to be assumed that the relationships studied are in some way “typical”—in general linear or a function that can be made linear. This assumption is false in our case, as the relationships that will be discussed change depending on the context analysed (see, for example, Fig. 1).

The period effect should still be included, especially with regard to the economic crisis of 2008–2009, along with the cohort effect connected to the different times at which subjects with different educational qualifications enter the labour market. The first effect was checked: the consequences of the crisis that hit Italy were yet to be felt in the last years considered. The situation of the cohort effect is more complicated, as 15 years or more can elapse between those with an elementary school diploma and graduates entering the labour market. Unfortunately, retrospective data are missing, but subjects born 10 years later—in the period 1964–1968—have a greater general propensity to look for employment. Nevertheless, much of this variation can be attributed to the increase in schooling and it follows that by examining de facto education all or most of the cohort effect is also checked.

The classification used here is CITP-88. The codes introduced in successive years and present in the microdata files (CP2001 and CP2011) do not vary in terms of general structure. The classifications of professions drawn up by Istat in Italy (with nine large groups) and by ISCO internationally (with 10 groups) coincide almost completely. The only difference is that Istat groups together ISCO values 6 and 7, which are respectively defined as: skilled agricultural and fishery workers, and craft and related trades workers.

The large group “armed forces” has been eliminated both for its scarceness (0.8 %) and because an extremely diverse range of skills are needed to carry out the tasks in the different jobs, to the extent that it is impossible to arrange them inside the classification used. Nevertheless, they have not been eliminated, but inserted into the median occupation for the educational qualification in question.

In concrete terms, the geographical areas considered include the following regions: North-West (Piedmont, Lombardy and Liguria), the Third Italy (Trentino Alto-Adige, Veneto and Friuli Venezia Giulia, Emilia-Romagna, Tuscany, Umbria and Marche), Lazio and the Adriatic Coast (Abruzzo, Molise, Puglia and Basilicata) and the South and the Islands (Campania, Calabria, Sicily and Sardinia).

1995 was chosen as it provided the first reliable data on the subject, while the last statistics available were from 2009.

The Italian reform aimed at increasing the retirement age to 65 for men and 60 for women has only shown its initial effects in recent years.

It is accepted that the correct statistic for ordinal variables is the median, which has been used in Table 4. By using this measure of central tendency, one could, however, make comparisons that would be too imprecise, as even small movements can cause changes in the level of occupation. This problem is eliminated by using the arithmetic mean. In this way, it is assumed that the different levels are “layered” in proportional terms. The approximation is acceptable in this case, as some extremely similar values are compared.

On the basis of the main study of a panel in the Italian labour market, there is a low level of individual mobility, as shown by the average number of episodes of use (Schizzerotto 2002).

In terms of occupation, these advantages are not necessarily accompanied by an economic benefit.

The data for those aged 35–40 can be obtained from Table 4, excluding the unemployed in the recalculation of fractions, while the table is not shown for those aged 50–55.

Ibidem.

References

AlmaLaurea: Condizione occupazionale dei laureati. XVI Indagine 2013. Consorzio Interuniversitario AlmaLaurea, Bologna (2014)

Ammermueller, A., Kuckulenz, A., Zwick, T.: Aggregate unemployment decreases individual returns to education. Econ. Educ. Rev. 28, 217–226 (2009)

Autor, D.H., Dor, D.: The growth of low-skill service jobs and the polarization of the US Labor Market. Am. Econ. Rev. 103(5), 1553–1597 (2013)

Bagnasco, A.: Tre Italie: la problematica territoriale dello sviluppo italiano. il Mulino, Bologna (1977)

Ballarino, G., Scherer, S.: More investment—less returns? Changing returns to education in Italy across three decades. Stato e Mercato 99, 359–388 (2013)

Becker, G.: Human Capital: A Theoretical and Empirical Analysis, with Special Reference to Education. National Bureau of Economic Research, New York (1964)

Berton, F., Richiardi, M., Sacchi, S.: Flex-insecurity. Perché in Italia la flessibilità diventa precarietà. il Mulino, Bologna (2009)

Blanchflower, D.G., Oswald, A.J.: An Introduction to the Wage Curve. J. Econ. Perspect. 9(3), 153–167 (1995)

Blossfeld, H.P., Hofmeister, H.: Globalization, Uncertainty and Women’s Careers. An International Comparison. Edward Elgar, Cheltenham (2006)

Blossfeld, H.P., Mills, M., Bernardi, F.: Globalization, Uncertainty and Men’s Careers. An International Comparison. Edward Elgar, Cheltenham (2006)

Blundell, R., Dearden, L., Sianesi, B.: Estimating the Returns to Education: Models, Methods and Results. CEEDP 16 (2001)

Brandolini, A., Cipollone, P., Viviano, E.: Does the ILO definition capture all unemployment? Temi di discussione del Servizio Studi Banca d’Italia 529 (2004)

Brynjolfsson, E., McAfee, A.: Race Against the Machine. Digital Frontier Press, Lexington (2011)

Calmfors, L., Driffill, J.: Bargaining structure, corporatism and macroeconomic performance. Econ. Policy 3(6), 13–62 (1988)

Card, D.: The causal effect of education on earnings. In: Ashenfelter, O., Card, D. (eds.) Handbook of Labor Economics, vol. 3, pp. 1801–1863. North-Holland, New York (1999)

Checchi, D.: Istruzione e mercato. Per una analisi economica della formazione scolastica. il Mulino, Bologna (1999)

Collins, R.: Functional and conflict theories of education stratification. Am. Sociol. Rev. 36(6), 1002–1019 (1971)

Dickson, M., Smith, S.: What determines the return to education: an extra year or a hurdle cleared? Econ. Educ. Rev. 30, 1167–1176 (2011)

Franzini, M., Raitano, M.: Wage Gaps and Human Capital: Looking for an Explanation. paper presented at the Fifth ECINEQ Conference, Bari, 22-24 July 2013 (2013)

Goos, M., Manning, A., Salomons, A.: Job polarization in Europe. Am. Econ. Rev. 99(2), 58–63 (2009)

Hall, P.A., Soskice, D. (eds.): Varieties of Capitalism: The Institutional Foundations of Comparative Advantage. Oxford University, Oxford (2001)

Harmon, C., Oosterbeek, H., Walker, I.: The returns to education: microeconomics. J. Econ. Surv. 17(2), 115–156 (2003)

Heckman, J.J.: Sample selection bias as a specification error. Econometrica 47(1), 153–161 (1979)

Heckman, J.J., Lochner, L.J., Todd, P.E.: Fifty years of mincer earnings regressions. IZA Discussion Paper Series 775 (2003)

Hoffmann, E.: International statistical comparisons of occupational and social structures: problems, possibilities and the role of isco-88. www.ilo.org/public/english/bureau/stat/isco/press1.htm (2004). Accessed 12 Feb 2015

Istat: La rilevazione sulle forze di lavoro: contenuti, metodologie, organizzazione. Istat, Roma (2006)

Istat: Forze di lavoro, Media 2006. Istat, Roma (2007)

Istat: Forze di lavoro, Media 2009. Istat, Roma (2010)

Istat: L’Italia in 150 anni, sommario di statistiche storiche. Cap. 10 Mercato del lavoro. Istat, Roma (2011)

Istat: La classificazione delle professioni. Istat, Roma (2013)

Jackson, J.F.L., O’Callaghan, E.M.: The Glass Ceiling Effect: A Misunderstood Form of Discrimination [Annotated Bibliography]. Institute on Race and Ethnicity, University of Wisconsin System, Milwaukee (2007)

Jackson, J.F.L., O’Callaghan, E.M.: What do we know about glass ceiling effects? A taxonomy and critical review to inform higher Education research. Res. High. Educ. 50(5), 460–482 (2009)

King, A.G.: Occupational choice, risk aversion, and wealth. Ind. Labor Relat. Rev. 27(4), 586–596 (1974)

Livi Bacci, M.: Avanti giovani, alla riscossa. Come uscire dalla crisi giovanile in Italia. il Mulino, Bologna (2008)

Lovaglio, P.G., Verzillo, S.: Heterogeneous economic returns to higher education: evidence from Italy. Qual. Quant. (2015). doi:10.1007/s11135

McGoldrick, K.: Do woman receive compensating wages for earnings uncertainty? South. Econ. J. 62(1), 210–222 (1995)

Mincer, J.: Schooling, Experience and Earnings. National Bureau of Economic Research, New York (1974)

OECD: Education at a Glance 2013: OECD Indicators. OECD Publishing, Paris (2013)

Oreopoulos, P., von Wachter, T., Heisz, A.: The short- and long-term career effects of graduating in a recession: hysteresis and heterogeneity in the market for college graduates. IZA Discussion Papers. 3578 (2008)

Reyneri, E.: Sociologia del mercato del lavoro. I. Il mercato del lavoro tra famiglia e welfare. Bologna, il Mulino (2005)

Schizzerotto, A.: (a cura di): Vite ineguali. Disuguaglianze e corsi di vita nell’Italia contemporanea. il Mulino, Bologna (2002)

Spence, M.: Job market signalling. Q. J. Econ. 87, 355–379 (1975)

Thurow, L.: Generating Inequalities. Basic Book, New York (1975)

Traxler, F., Blaschke, S., Kittel, B.: National Labour Relations in Internationalized Markets. A Comparative Study of Institutions. Oxford University Press, Oxford (2001)

Trigilia, C.: Sviluppo senza autonomia: effetti perversi delle politiche nel Mezzogiorno. il Mulino, Bologna (1992)

Triventi, M.: The gender wage gap and its institutional context: a comparative analysis of European graduates. Work Employ. Soc. 27(4), 563–580 (2013)

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Appendix: Coding of educational qualifications (ISCED classification)

Appendix: Coding of educational qualifications (ISCED classification)

The ISCED classifications have changed significantly over the years. Here we only show the main categories with the relative groupings.

-

(a)

Elementary school diploma;

-

(b)

Middle school diploma;

-

(c)

Professional school diploma (4–5 years). Professional qualification (2–3. does not allow entry to university). Art institute qualification (I cycle). Secondary school diploma in education (short cycle). Other qualification or diploma;

-

(d)

5-year high school diploma. Allows entry to university.

-

(e)

Degree or university diploma including

-

Economic/social economic–statistical, political–social, legal;

-

Humanities literary, linguistic, teaching, psychological, physical education, fine arts;

-

Engineering engineering, architecture;

-

Scientific scientific, chemical–pharmaceutical, geo-biological, Agrarian;

-

Medical medicine;

-

General other degree or university diploma.

-

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Scappini, E., Trentini, M. Education and employment in Italy of the cohort of adults born in 1954–1958: an analysis from 1993 to 2009. Qual Quant 50, 1611–1631 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11135-015-0223-z

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11135-015-0223-z