Abstract

Many scholars have argued that primary elections are an important factor in the polarization of the American Congress. Yet little research measures change in the policy preferences of primary electorates to evaluate the connection directly. We create the first explicit measures of the preferences of primary voters over the last 60 years using a Bayesian item-response theory model. Although the overall distribution of population preferences has changed little, the preferences of primary voters are now much more related to the party of the primary that they attend. We show that liberals are much more likely to turn out in Democratic primaries and conservatives are much more likely to turn out in Republican primaries. We estimate that the divergence of primary from general electorates is six times larger in 2012 than in 1958 owing to this “primary sorting”. This trend began with the emergence of the Southern Republicans. As the Republican party became viable, conservative Southerners switched to Republican primaries leading to a leftward shift in Democratic primary electorates. Nationwide, primary sorting began sometime after it began in the South. We speculate that Southern realignment played a clarifying role that contributed to subsequent sorting of primary electorates nationwide.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

McKee and Hayes (2009) considers primary elections from 1988 to 2008, finding that the electorate has polarized in the South in terms of self-identified liberalism and conservatism, as well as race. Our time series begins in 1958 and we measure preferences using responses to questions about policy.

Party sorting in most scholarship is defined as the increasing correspondence between party identification, as measured by survey responses, and ideology. We define a behavioral analog of party sorting called primary sorting that is the increasing correspondence between the party primary that an individual chooses to vote in and their ideology.

This is consistent with Erikson et al. (1993, pp. 17–20), who find little correlation between ideology and partisanship across states, averaging over the 1976–1988 period.

We assume that primary voters are at least partially expressive in their behavior. Fully strategic primary voters might have nominated the best candidate for the general election, even if they had more extreme preferences (e.g., Aranson and Ordeshook 1972; Coleman 1971). We also note that causality might have operated in the opposite direction, from Congress to the composition of primary electorates.

This rightward move was not without consequences, however, particularly the loss of the moderate Republican foothold in the northeast (Reiter and Stonecash 2011).

Hill and Tausanovitch (2015) show in an Appendix that when these responses are assumed to be comparable for only short lengths of time, the results are similar.

The model itself is similar to Poole and Rosenthal ’s (2000) W-NOMINATE or Clinton et al. ’s (2004) IDEAL. An important difference is that the multinomial link function allows the model to use all of the response categories to inform the respondents’ latent ideology, which is valuable for many of the survey questions that have more than two responses. “Don’t know” responses are set as missing values.

For example, “We find that a lot of people don’t pay much attention to primary elections. Do you remember whether or not you voted in the primary election for congressman this year?” (1958) or “Your state held a primary election on (DATE). Did you vote in that election, or were you unable to do so?” (1980).

Turnout in congressional primaries was asked in 1958, 1964, 1966 and 1978, with questions about presidential pimaries in other years. Primary participation was not asked of half of the 1972 sample and 172 cases of the 1992 sample who were given the form 2 questionnaire in those years. We limit analysis to form 1 respondents.

The records from 1978 are validated to administrative records with party of primary the party of registration for the validated voter, question numbers V781411 and V781401.

In “Appendix”, we explore whether sorting among primary voters is greater than sorting among partisan identifiers, finding some evidence in support of greater sorting of primary voters.

To estimate, we calculate the rate of primary participation by (across-year) ideology decile from 1958, then sample primary voters at random from 2012 respondents given their ideology decile and the 1958 rate of primary participation and assign them to a party primary based on their 2012 party identification. We apply this sampling strategy at each posterior iteration, calculate the party medians, and present the posterior median and credible interval of the distance between medians in the figure, which captures both uncertainty in respondent ideology and sampling variability in simulated turnout.

To estimate, we calculate the rate of participation in each party primary in each (across-year) decile of ideology in 1958, then sample a counterfactual party primary for each 2012 respondent given their ideology decile and the 1958 rate of participation in each primary. We then used observed 2012 primary turnout to describe the primary voters. We sample party primary at each posterior iteration, calculate the party medians, and present the posterior median and credible interval of the distance between medians in the figure.

Following the coding in the ANES, the set of states coded as “South” here are Alabama, Arkansas, Delaware, Washington, DC, Florida, Georgia, Kentucky, Louisiana, Maryland, Mississippi, North Carolina, Oklahoma, South Carolina, Tennessee, Texas, Virginia and West Virginia. We choose a broad definition of the South in order to err on the conservative side in our results. If we have included states that rightfully belong in another region, our findings will be weaker as a result.

In “Appendix”, we explore whether sorting among primary voters is greater than sorting among partisan identifiers, by region.

See http://www.voteview.com/Weekly_Constant_Space_DW-NOMINATE_Scores.htm. Accessed February 22, 2016.

References

American National Election Studies. (2014). The American National Election Studies (www.electionstudies.org) Time Series Cumulative Data File [dataset]. Stanford, CA: Stanford University and the University of Michigan [producers and distributors].

Aranson, P. H., & Ordeshook, P. C. (1972). Spatial strategies for sequential elections. In R. G. Niemi & H. F. Weisberg (Eds.), Probability models of collective decision making. Columbus: Charles E. Merrill Publishing Co.

Black, E., & Black, M. (2009). The rise of southern Republicans. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Black, M. (1978). Racial composition of congressional districts and support for federalvoting rights In the American south. Social Science Quarterly, 59(3), 435–450.

Brady, D. W., Han, H., & Pope, J. C. (2007). Primary elections and candidate ideology: Out of step with the primary electorate? Legislative Studies Quarterly, 32(1), 79–105.

Bullock, W., & Clinton, J. D. (2011). More a molehill than a mountain: The effects of the blanket primary on elected officials behavior from California. The Journal of Politics, 73(03), 915–930.

Carmines, E. G., & Stimson, J. A. (1980). The two faces of issue voting. American Political Science Review, 74(01), 78–91.

Carmines, E. G., & Stimson, J. A. (1989). Issue evolution: Race and the transformation of American politics. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Clinton, J., Jackman, S., & Rivers, D. (2004). The statistical analysis of roll call data. American Political Science Review, 98(02), 355–370.

Coleman, J. S. (1971). Internal processes governing party positions in elections. Public Choice, 11, 35–60.

Erikson, R. S., Wright, G. C., & McIver, J. P. (1993). Statehouse democracy: Public opinion and policy in the American states. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Fiorina, M. P., & Abrams, S. J. (2008). Political polarization in the American public. Annual Review of Political Science, 11, 563–588.

Fiorina, M. P., & Abrams, S. J. (2012). Disconnect: The breakdown of representation in American politics. Julian J. Rothbaum Distinguished Lecture Series. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press.

Fiorina, M. P., Abrams, S. A., & Pope, J. C. (2008). Polarization in the American public: Misconceptions and misreadings. The Journal of Politics, 70(02), 556–560.

Fiorina, M. P., Abrams, S. J., & Pope, J. (2005). Culture war?. New York: Pearson Longman.

Gerber, A. S., Huber, G. A., & Washington, E. (2010). Party affiliation, partisanship, and political beliefs: A field experiment. American Political Science Review, 104(4), 720–744.

Han, H., & Brady, D. W. (2007). A delayed return to historical norms: Congressional party polarization after the Second World War. British Journal of Political Science, 37(03), 505–531.

Hetherington, M. J. (2009). Review article: Putting polarization in perspective. British Journal of Political Science, 39(02), 413–448.

Hill, S. J. (2015). Institution of nomination and the policy ideology of primary electorates. Quarterly Journal of Political Science, 10(4), 461–487.

Hill, S. J., & Tausanovitch, C. (2015). A disconnect in representation? Comparison of trends in congressional and public polarization. The Journal of Politics, 77(4), 1058–1075.

Hirano, S., Snyder, J. M, Jr., Ansolabehere, S., & Hansen, J. M. (2010). Primary elections and partisan polarization in the US Congress. Quarterly Journal of Political Science, 5, 169–191.

Hood, M. V., Kidd, Q., & Morris, I. L. (2001). The key issue: Constituency effects and southern senators’ roll-call voting on civil rights. Legislative Studies Quarterly, 26(4), 599–621.

Jacobson, G. C. (2003). Partisan polarization in presidential support: The electoral connection. Congress & the Presidency: A Journal of Capital Studies, 30(1), 1–36.

Jacobson, G. C. (2012). The electoral origins of polarized politics evidence from the 2010 cooperative congressional election study. American Behavioral Scientist, 56(12), 1612–1630.

Key, V. O. (1949). Southern politics in state and nation. New York: Knopf.

Levendusky, M. (2009a). The partisan sort: How liberals became Democrats and conservatives became Republicans. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Levendusky, M. S. (2009b). The microfoundations of mass polarization. Political Analysis, 17(2), 162–176.

Levendusky, M. S. (2010). Clearer cues, more consistent voters: A benefit of elite polarization. Political Behavior, 32(1), 111–131.

McCarty, N., Poole, K. T., & Rosenthal, H. (2009). Does gerrymandering cause polarization? American Journal of Political Science, 53(3), 666–680.

McCarty, N. M., Poole, K. T., & Rosenthal, H. (2006). Polarized America: The dance of ideology and unequal riches. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

McGhee, E., Masket, S., Shor, B., Rogers, S., & McCarty, N. (2014). A primary cause of partisanship? Nomination systems and legislator ideology. American Journal of Political Science, 58(2), 337–351.

McKee, S. C., & Hayes, D. (2009). Polls and elections: Dixie’s Kingmakers: Stability and change in southern presidential primary electorates. Presidential Studies Quarterly, 39(2), 400–417.

Nivola, P. S., & Brady, D. W. (2007). Red and blue nation? Characteristics and causes of America’s polarized politics (Vol. 1). Washington, DC: Brookings Institution Press.

Norrander, B., & Wendland, J. (2016). Open versus closed primaries and the ideological composition of presidential primary electorates. Electoral Studies, 42, 229–236.

Polsby, N. W. (2005). How Congress evolves: Social bases of institutional change. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Poole, K. T., & Rosenthal, H. (2000). Congress: A political-economic history of roll call voting. Oxford University Press on Demand.

Reiter, H. L., & Stonecash, J. M. (2011). Counter realignment: Political change in the northeastern United States. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Schickler, E. (2016). Racial realignment: the transformation of American liberalism, 1932–1965. Princeton studies in American politics: Historical, international, and comparative perspectives. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Shafer, B. E., & Johnston, R. (2009). The end of Southern exceptionalism: Class, race, and partisan change in the postwar South. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Sides, J. M., Tausanovitch, C., Warshaw, C., & Vavreck, L. (2014). On the representativeness of primary voters. In The Annual Midwestern Political Science Association Conference.

Theriault, S. M. (2006). Party polarization in the US Congress member replacement and member adaptation. Party Politics, 12(4), 483–503.

Thomsen, D. M. (2014). Ideological moderates won’t run: How party fit matters for partisan polarization in Congress. The Journal of Politics, 76(03), 786–797.

Vavreck, L. (2007). The exaggerated effects of advertising on turnout: The dangers of self-reports. Quarterly Journal of Political Science, 2(4), 325–343.

Voteview Blog, The. (2015). Polarization continues through 2015. (December 28).

Acknowledgements

We thank Sara Kerosky for research assistance and Greg Huber, Gary Jacobson, Matt Levendusky, Nolan McCarty, and participants in the 2016 Arizona State University Goldwater Conference for valuable feedback.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Appendix

Appendix

1.1 Validated versus self-reported primary turnout

One concern with our analysis is that our measure of participation in primary elections is self-reported in all cases by one. It is well known that citizens overreport turnout. As a result, our findings may be influenced by respondents who claim to have voted in one of the party primaries but actually did not do so. To evaluate whether this measurement problem affects our conclusions, we use the 1980 version of the ANES, which both asked for self-reports of primary turnout and validated the primary turnout of most respondents using administrative records. We show that patterns of turnout by ideology decile are highly similar regardless of which measure we use.

The sample for this study are the 1608 respondents to the 1980 ANES for whom Hill and Tausanovitch (2015) estimated ideology. We exclude the 595 cases wherein a registration record was not found, as well as the 224 respondents who resided in states without presidential primaries in 1980.

Among those who self-reported a primary election vote, resided in states holding presidential primaries, and were matched to voter files, 70.8% had validated records of primary turnout. In contrast, 5.8% of those who said they did not vote actually did vote according to the administrative records. Not surprisingly, primary voting is overreported.

Conditional on turning out, few respondents report voting in a different primary than the one reported in the administrative records. Among those who report turning out and have a validated record of voting, only 1.3% of those who claimed to have voted in the Democratic presidential primary were validated as having voted in the Republican primary, while 4.6% of those who claimed to have voted in the Republican presidential primary were validated to have voted in the Democratic primary.

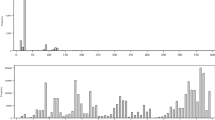

Our measures of the ideology of the primary electorate are very similar results regardless of whether we use validated turnout or self-reports. The median ideology for self-reported Democratic and Republican primary voters in 1980 are \(-\,0.17\) [\(-\,0.29, -\,0.05\)] and 0.35 [0.20, 0.49], 95% credible intervals in brackets. The same values for validated Democratic and Republican primary voters in 1980 are \(-\,0.17\) [\(-\,0.31, -\,0.03\)] and 0.34 [0.16, 0.53]. In Fig. 8, we plot the posterior median rate of turnout in each decile of ideology measured with the administrative records (y-axis) against the same rate measured with self-reports (x-axis). The figure shows that turnout is overreported, but that this overreporting is linear. In other words, each decile of ideology has a roughly equal tendency towards overreporting.

Rates of turnout by decile of ideology 1980. Note: Each point is the rate of primary turnout among that decile of ideology (1 = most liberal 10%, 10 = most conservative 10% in that year) in 1980, with location on the x-axis self-reported and location on the y-axis validated. Limited to cases matched to voter files

The evidence suggests that inferences about primary ideology and polarization are not affected by the use of self-reported turnout, at least in the case of 1980 (Fig. 8).

1.2 Population level distribution of ideology over time

The total height of each bar in Fig. 9 corresponds to the number of all respondents who had an ideology score in that bin (ideology varies from liberal in the negative direction to conservative in the positive direction, with mean zero and unit variance across all years). The grey portion of each bar represents the proportion of respondents at each ideological position who did not vote in any primary. The red portion of each bar represents those who turned out in a Republican primary, and the blue portion those who voted in a Democratic primary. Readers may be surprised to see that the red and blue portions of the distributions are often centered close to one another, particularly in the early years of the ANES. In these early years, the major parties had not yet sorted effectively by policy ideology. Over the second half of the 20th century, voters became more aware of the policy stances of the respective parties, and have demonstrated a slow but consistent tendency to join the party that better matches their policy positions (Levendusky 2009b).

Ideology of Americans and primary voters, 1958–2012. Note: The full histogram represents the policy ideology for all respondents in that year from the American National Election Studies. The interior bar heights represent the distributions of ideology among voters in Democratic (blue) and Republican (red) primaries in that year. Years limited to ANES surveys with primary turnout records. (Color figure online)

1.3 Sorting of primary voters versus partisanship

In Fig. 10, we compare party sorting among primary voters (as in Fig. 6 above) to sorting among partisan identifiers (including leaners) regardless of turnout, by region. In general, the two groups show similar levels of sorting, with primary voters more conservative in both parties historically, but with primary voters becoming more extreme than identifiers in the latest two elections. These differences are small, but the general conclusion is that primary voters are sorting to a greater extent, relative to their 1958 disposition, than party identifiers, in both regions. Particularly in the South relative to 1958 alignment, primary medians have moved more than identifier medians. The fact that primary sorting is even greater than party sorting suggests that party sorting occurred to a greater degree among primary voters. Previous work has not shown that party sorting affected the composition of primaries, or that primary sorting differed by region.

Polarization in primary electorate versus partisanship by region, 1958–2012. Note: Each point represents the distance from the median voter in that party’s primary electorate (closed circles) or among that party’s partisan identifiers in the population (open squares) to the median voter in the general electorate in that year

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Hill, S.J., Tausanovitch, C. Southern realignment, party sorting, and the polarization of American primary electorates, 1958–2012. Public Choice 176, 107–132 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11127-017-0478-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11127-017-0478-0