Abstract

Purpose

Drug-induced liver injuries (DILI) comprise a significant proportion of adverse drug reactions leading to hospitalizations and death. One frequent DILI is granulomatous inflammation from exposure to harmful metabolites that activate inflammatory pathways of immune cells of the liver, which may act as a barrier to isolate the irritating stimulus and limit tissue damage.

Methods

Paralleling the accumulation of CFZ precipitates in the liver, granulomatous inflammation was studied to gain insight into its effect on liver structure and function. A structural analog that does not precipitate within macrophages was also studied using micro-analytical approaches. Depleting macrophages was used to inhibit granuloma formation and assess its effect on drug bioaccumulation and toxicity.

Results

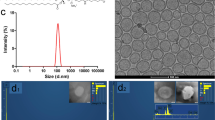

Granuloma-associated macrophages showed a distinct phenotype, differentiating them from non-granuloma macrophages. Granulomas were induced by insoluble CFZ cargo, but not by the more soluble analog, pointing to precipitation being a factor driving granulomatous inflammation. Granuloma-associated macrophages showed increased activation of lysosomal master-regulator transcription factor EB (TFEB). Inhibiting granuloma formation increased hepatic necrosis and systemic toxicity in CFZ-treated animals.

Conclusions

Granuloma-associated macrophages are a specialized cell population equipped to actively sequester and stabilize cytotoxic chemotherapeutic agents. Thus, drug-induced granulomas may function as drug sequestering “organoids” –an induced, specialized sub-compartment– to limit tissue damage.

Similar content being viewed by others

Abbreviations

- ADR:

-

Adverse Drug Reaction

- CFZ:

-

Clofazimine

- CLDI:

-

Crystal-Like Drug Inclusion

- DILI:

-

Drug-induced liver injury

- IL-1RA:

-

Interleukin-1 Receptor Antagonist

- LAMP1:

-

Lysosomal Associated Membrane Protein 1

- LC3:

-

Microtubule-associated protein 1A/1B-light chain 3

- TFEB:

-

Transcription Factor EB

- TLR9:

-

Toll-Like Receptor 9

- TUNEL:

-

Terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase (TdT) dUTP Nick-End Labeling

References

Greenberg AS, Obin MS. Obesity and the role of adipose tissue in inflammation and metabolism. Am J Clin Nutr. 2006;83(2):461S–5S.

Monteiro R, Azevedo I. Chronic inflammation in obesity and the metabolic syndrome. Mediat Inflamm. 2010;2010:1–10.

Crusz SM, Balkwill FR. Inflammation and cancer: advances and new agents. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 2015;12(10):584–96.

Coussens LM, Werb Z. Inflammation and cancer. Nature. 2002;420(6917):860–7.

Coash M, Forouhar F, Wu CH, Wu GY. Granulomatous liver diseases: a review. J Formos Med Assoc. 2012;111(1):3–13.

Brito T, Franco MF. Granulomatous inflammation. Rev Inst Med Trop Sao Paulo. 1994;36:185–92.

Zumla A, James DG. Granulomatous infections: etiology and classification. Clin Infect Dis. 1996;23(1):146–58.

Bhat RM, Prakash C. Leprosy: An overview of pathophysiology. Int Perspect Infect Dis. 2012;2012:6.

Silva Miranda M, Breiman A, Allain S, Deknuydt F, Altare F. The tuberculous granuloma: an unsuccessful host Defence mechanism providing a safety shelter for the Bacteria? Clin Dev Immunol. 2012;2012:14.

Freeman HJ. Granuloma-positive Crohn’s disease. Can J Gastroenterol. 2007;21(9):583–7.

Henry L, Wagner B, Faulkner MK, Slater DN, Ansell ID. Metal deposition in post-surgical granulomas of the urinary tract. Histopathology. 1993;22(5):457–65.

Culver EL, Watkins J, Westbrook RH. Granulomas of the liver. Clin Liver Dis. 2016;7(4):92–6.

Espiritu CR, Kim TS, Levine RA. Granulomatous hepatitis associated with sulfadimethoxine hypersensitivity. JAMA. 1967;202(10):985–8.

Bramlet DA, Posalaky Z, Olson R. Granulomatous hepatitis as a manifestation of quinidine hypersensitivity. Arch Intern Med. 1980;140(3):395–7.

Nguyen-Lefebvre AT, Horuzsko A. Kupffer cell metabolism and function. J Enzymol Metab. 2015;1(1).

Milosevic N, Schawalder H, Maier P. Kupffer cell-mediated differential down-regulation of cytochrome P450 metabolism in rat hepatocytes. Eur J Pharmacol. 1999;368(1):75–87.

Ding H, Tong J, Wu SC, Yin DK, Yuan XF, Wu JY, et al. Modulation of Kupffer cells on hepatic drug metabolism. World J Gastroenterol. 2004;10(9):1325–8.

Laskin DL. Parenchymal and nonparenchymal cell interactions in hepatotoxicity. Adv Exp Med Biol. 1991;283:499–505.

Roberts RA, Ganey PE, Ju C, Kamendulis LM, Rusyn I, Klaunig JE. Role of the Kupffer cell in mediating hepatic toxicity and carcinogenesis. Toxicol Sci. 2007;96(1):2–15.

Kegel V, Pfeiffer E, Burkhardt B, Liu JL, Zeilinger K, Nüssler AK, et al. Subtoxic concentrations of hepatotoxic drugs Lead to Kupffer cell activation in a human in vitro liver model: an approach to study DILI. Mediat Inflamm. 2015;2015:14.

Cholo M, Steel H, Fourie P, Germishuizen W, Anderson R. Clofazimine: current status and future prospects. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2011.

Tyagi S, Ammerman NC, Li SY, Adamson J, Converse PJ, Swanson RV, et al. Clofazimine shortens the duration of the first-line treatment regimen for experimental chemotherapy of tuberculosis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2015;112(3):869–74.

DrugBank. Clofazimine. In. drugbank.ca; 2013.

Yoon GS, Keswani RK, Sud S, Rzeczycki PM, Murashov MD, Koehn TA, et al. Clofazimine biocrystal accumulation in macrophages upregulates interleukin 1 receptor antagonist production to induce a systemic anti-inflammatory state. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2016;60(6):3470–9.

Trexel J, Yoon GS, Keswani RK, McHugh C, Yeomans L, Vitvitsky V, et al. Macrophage-mediated Clofazimine sequestration is accompanied by a shift in host energy metabolism. J Pharm Sci. 2017;106(4):1162–74.

Baik J, Stringer KA, Mane G, Multiscale Distribution RGR. Bioaccumulation analysis of Clofazimine reveals a massive immune system-mediated xenobiotic sequestration response. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2013;57(3):1218–30.

Baik J, Rosania GR. Macrophages sequester Clofazimine in an intracellular liquid crystal-like supramolecular organization. PLoS One. 2012;7(10):e47494.

Yoon G, Sud S, Keswani R, Baik J, Standiford T, Stringer K, et al. Phagocytosed Clofazimine biocrystals can modulate innate immune signaling by inhibiting TNF alpha and boosting IL-1RA secretion. Mol Pharm. 2015;12:2517–27.

Keswani R, Baik J, Yeomans L, Hitzman C, Johnson A, Pawate A, et al. Chemical analysis of drug biocrystals: a role for Counterion transport pathways in intracellular drug disposition. Mol Pharm. 2015;12:2528–36.

Kaluarachchi SI, Fernandopulle BM, Gunawardane BP. Hepatic and haematological adverse reactions associated with the use of multidrug therapy in leprosy--a five year retrospective study. Indian J Lepr. 2001;73(2):121–9.

Singh H, Nel B, Dey V, Tiwari P, Dulhani N. Adverse effects of multi-drug therapy in leprosy, a two years' experience (2006-2008) in tertiary health care Centre in the tribal region of Chhattisgarh state (Bastar, Jagdalpur). Lepr Rev. 2011;82(1):17–24.

Murray PJ, Wynn TA. Protective and pathogenic functions of macrophage subsets. Nat Rev Immunol. 2011;11(11):723–37.

Rzeczycki P, Yoon GS, Keswani RK, Sud S, Stringer KA, Rosania GR. Detecting ordered small molecule drug aggregates in live macrophages: a multi-parameter microscope image data acquisition and analysis strategy. Biomed Opt Express. 2017;8(2):860–72.

Schneider CA, Rasband WS, Eliceiri KW. NIH Image to ImageJ: 25 years of image analysis. Nat Methods. 2012;9(7):671–5.

Lin S, Racz J, Tai M, Brooks K, Rzeczycki P, Heath L, et al. A role for low density lipoprotein receptor-related protein 1 in the cellular uptake of tissue plasminogen activator in the lungs. Pharm Res. 2015:1–11.

Keswani RK, Yoon GS, Sud S, Stringer KA, Rosania GR. A far-red fluorescent probe for flow cytometry and image-based functional studies of xenobiotic sequestering macrophages. Cytometry A. 2015;87(9):855–67.

Min KA, Rajeswaran WG, Oldenbourg R, Harris G, Keswani RK, Chiang M, et al. Massive Bioaccumulation and Self-assembly of Phenazine compounds in live cells. Adv Sci. 2015;2(8).

van Rooijen N, Hendrikx E. Liposomes for specific depletion of macrophages from organs and tissues. In: Weissig V, editor. Liposomes: Humana Press; 2010. p. 189–203.

Murashov MD, LaLone V, Rzeczycki PM, Keswani RK, Yoon GS, Sud S, Rajeswaran W, Larsen S, Stringer KA, Rosania GR. The physicochemical basis of Clofazimine-induced skin pigmentation. J Investig Dermatol 2017.

Keswani R, Yoon G, Sud S, Stringer K, Rosania G. A far-red fluorescent probe for flow cytometric xenobiotic-sequestering cell functional Studies. Cytometry Part A 2015 (Accepted Manuscript).

Zhitomirsky B, Assaraf YG. Lysosomal sequestration of hydrophobic weak base chemotherapeutics triggers lysosomal biogenesis and lysosome-dependent cancer multidrug resistance. Oncotarget. 2015;6(2):1143–56.

Kaufmann AM, Krise JP. Lysosomal sequestration of amine-containing drugs: analysis and therapeutic implications. J Pharm Sci. 2007;96(4):729–46.

Logan R, Kong AC, Axcell E, Krise JP. Amine-containing molecules and the induction of an expanded lysosomal volume phenotype: a structure–activity relationship study. J Pharm Sci. 2014;103(5):1572–80.

Zhitomirsky B, Assaraf YG. Lysosomal accumulation of anticancer drugs triggers lysosomal exocytosis. Oncotarget. 2017;8(28):45117–32.

Andrejewski N, Punnonen E-L, Guhde G, Tanaka Y, Lüllmann-Rauch R, Hartmann D, von Figura K, Saftig P. Normal lysosomal morphology and function in LAMP-1-deficient mice. J Biol Chem 1999;274(18):12692–12701.

Tanida I, Ueno T, Kominami E. LC3 and Autophagy. Methods Mol Biol (Clifton, NJ). 2008;445:77–88.

Sri-Pathmanathan RM, Plumb JA, Fearon KC. Clofazimine alters the energy metabolism and inhibits the growth rate of a human lung-cancer cell line in vitro and in vivo. Int J Cancer. 1994;56(6):900–5.

Stokes WS. Humane endpoints for laboratory animals used in regulatory testing. ILAR J. 2002;43(Suppl_1):S31–8.

Lee WM. Drug-induced hepatotoxicity. N Engl J Med. 2003;349(5):474–85.

Hodgman MJ, Garrard AR. A review of acetaminophen poisoning. Crit Care Clin. 2012;28(4):499–516.

Dunne DW, Jones FM, Doenhoff MJ. The purification, characterization, serological activity and hepatotoxic properties of two cationic glycoproteins (alpha 1 and omega 1) from Schistosoma mansoni eggs. Parasitology. 1991;103(Pt 2):225–36.

Lundy SK, Lukacs NW. Chronic schistosome infection leads to modulation of granuloma formation and systemic immune suppression. Front Immunol. 2013;4:39.

Hams E, Aviello G, Fallon PG. The schistosoma granuloma: friend or foe? Front Immunol. 2013;4:89.

Miller AC Jr, Reid WM. Methyldopa-induced granulomatous hepatitis. JAMA. 1976;235(18):2001–2.

Ishak KG, Kirchner JP, Dhar JK. Granulomas and cholestatic--hepatocellular injury associated with phenylbutazone. Report of two cases. Am J Dig Dis. 1977;22(7):611–7.

Roczniak-Ferguson A, Petit CS, Froehlich F, Qian S, Ky J, Angarola B, et al. The transcription factor TFEB links mTORC1 signaling to transcriptional control of lysosome homeostasis. Sci Signal. 2012;5(228):ra42.

Peña-Llopis S, Vega-Rubin-de-Celis S, Schwartz JC, Wolff NC, TAT T, Zou L, et al. Regulation of TFEB and V-ATPases by mTORC1. EMBO J. 2011;30(16):3242–58.

Giatromanolaki A, Kalamida D, Sivridis E, Karagounis IV, Gatter KC, Harris AL, et al. Increased expression of transcription factor EB (TFEB) is associated with autophagy, migratory phenotype and poor prognosis in non-small cell lung cancer. Lung Cancer. 2015;90(1):98–105.

Perera RM, Stoykova S, Nicolay BN, Ross KN, Fitamant J, Boukhali M, et al. Transcriptional control of autophagy-lysosome function drives pancreatic cancer metabolism. Nature. 2015;524(7565):361–5.

Fang LM, Li B, Guan JJ, Xu HD, Shen GH, Gao QG, et al. Transcription factor EB is involved in autophagy-mediated chemoresistance to doxorubicin in human cancer cells. Acta Pharmacol Sin. 2017;38(9):1305–16.

Acknowledgments and Disclosures

The authors thank Eric Bushong and Mark Ellisman for helping us with electron microscopy analysis done at the National Center for Microscopy and Imaging Research, University of California San Diego. The authors would also like to acknowledge support received from the Upjohn Research Award presented to GRR by the University Of Michigan College Of Pharmacy. This work was supported by NIH grant R01GM078200 to GRR.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

P.R., G.S.Y, J.B., K.A.S. and G.R.R designed the research. P.R., G.S.Y., J.B., E.B., and M.E. conducted the experiments. G.R.R. and K.A.S. contributed new reagents and analytical tools. P.R., G.S.Y and I. B. analyzed the data. P.R., G.S.Y., I.B., K.A.S. and G.R.R. wrote or contributed to the writing of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Rzeczycki, P., Yoon, G.S., Keswani, R.K. et al. An Expandable Mechanopharmaceutical Device (2): Drug Induced Granulomas Maximize the Cargo Sequestering Capacity of Macrophages in the Liver. Pharm Res 36, 3 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11095-018-2541-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11095-018-2541-z