Abstract

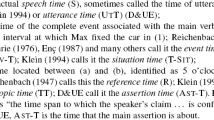

In the present paper, inspired by María J. Arche’s work, “The construction of viewpoint aspect: the imperfective revisited” (2013, this issue), I add several pieces of evidence in favor of her proposal that viewpoint aspect does not alter the fundamental situation aspect properties of predicates. Namely, I discuss the temporal interpretations in Capeverdean, a Portuguese-based Creole language for which the salient opposition in the domain of viewpoint aspect is not between the imperfective and the perfective, but rather between the Progressive and the Perfect, here taken as semantically complex categories that involve certain temporal characteristics; crucially, imperfectivity is one of the features of the Progressive and a perfective viewpoint is part of the semantic complexity of the Perfect. I also discuss the role of for-time durational adverbials when combined with the perfective and propose that, in their presence, the relevant final boundary when telic predicates are at stake is not the culmination of the event, but rather the final point described by that time-argument. This proposal accounts nicely for the fact that, in these specific contexts, there is no contradiction in having this perfective clause conjoined with the assertion that the underlying telic situation is not completed.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

List of abbreviations: 1sg/1pl—1st person singular/plural, etc.; comp—complementizer; hab—habitual; impf—imperfect; neg—negation; pft—perfect; poss—possessive; prep—preposition; pres—present; prog—progressive; pst—past; tma—temporal morpheme (this is used in some cases for preverbal ta, which has a complex aspectual and modal function for Capeverdean preverbal).

Hallman (2009b), among others, has discussed several diagnostics to distinguish dynamic events combined with the progressive from stative situations: their interaction with agent-oriented modifiers (eventive sentences in the progressive support them, states do not) or their behaviour in pseudocleft constructions (eventive sentences in the progressive cannot occur in them, but states can).

Rothstein (2004), among others, has defended that, when achievements seem to occur in the progressive, what really happens is that there is a shift from an achievement-type event to an accomplishment-type event. Crucially, even if this proposal is right, this is an operation between telic events, not a type of de-telecization.

There are two other postverbal morphemes, -du and -da, which occur in passives, but I will not discuss them here, since passive constructions are out of the scope of this paper.

Demirdache and Uribe-Etxebarria (2007, 2014, this issue) incorporate (im)perfective aspect within their model, on the assumption that the ordering relation holding between the AST-T and the EV-T (which aspect serves to specify) can be established via anaphora. They argue that when temporal anaphora involves coreference, the resulting viewpoint will be perfective, and when temporal anaphora involves binding, the resulting viewpoint will be imperfective. I leave the consequences of this for future research.

I do not consider here the label REF-T for the external arguments of TP and of AspP, and go straight to the fact that, in this case, these reference times correspond, respectively, to the Utterance Time and to the Assertion Time.

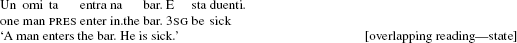

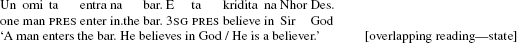

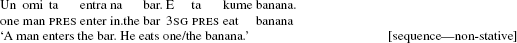

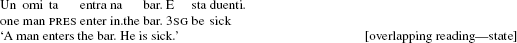

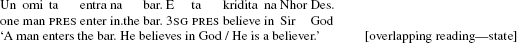

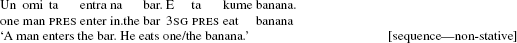

For the discussion of some stative properties of predicates like kridita na Nhor Des ‘believe in God’, see Pratas (2012), where, among other features, their temporal reading in a narrative has been tested. The line of reasoning behind this diagnostics goes as follows: eventive predicates advance the reference time in a narrative, whereas stative predicates do not (Kamp and Reyle 1993). Thus, we obtain the following contrast:

-

(i)

-

(ii)

-

(iii)

I am grateful to Peter Hallman (p.c.) for the suggestion of this test.

A final note on this is about the gloss pres (and not hab) for the morpheme ta in these cases: in Capeverdean, only in narratives may the present tense have a non-generalizing interpretation. (See Smith 2003 for a discussion on the various aspectual entities and tense in different discourse modes in English; I argue that some of these effects also hold in Capeverdean.)

-

(i)

Hallman (2009a:30) argues that “lexical telicity does not manifest itself as a completion entailment except in connection with a completiveness operator, a null counterpart to the progressive morpheme in English. This analysis is essentially the inverse of the more common approach […] that takes the progressive operator to remove a completion entailment inherent in its base, but is supported by the interaction of proportionality and aspect […]”

The less natural combination of specific situation types with each of these morphemes—for instance, states whose descriptions involve the copulas e and sta (be individual-level and be stage level, respectively) do not combine with the Null Perfect, and these and some other states do not combine with sata—is not unexpected; these restrictions have been attested for other languages and have been subject to intense debate, but I will not concentrate on them here.

We also tested a third combination, which involves two expressions marking a clearly perfective/closed interpretation of dynamic predicates: dja ka for activities and accomplishments, dja for achievements. These are not included here for two reasons: (i) the main point in our study, and also in the present paper, is to show the behaviour of children regarding the bare forms of predicates as opposed to the progressive; (ii) these expressions are more complex than the temporal morphemes: dja is more similar to an adverbial and dja ka involves a form of the aspectual auxiliary kaba ‘finish’; thus, it is not clear whether the comparison would be useful for our purposes.

Since there is no morphological marking for (non)finiteness in the language, these results can perhaps feed some future discussion about the true essence of (non)finiteness.

Smith (1991:107) also points out that, when we have a perfective aspect (and the examples that she presents include no durational adverbials), it is natural to infer that the telic event has been completed, since we are given no information to the contrary.

References

Arche, María J. 2006. Individuals in time. Tense, aspect and the individual/stage distinction. Amsterdam/Philadelphia: John Benjamins.

Arche, María J. 2013. The construction of viewpoint aspect: The imperfective revisited. Natural Language & Linguistic Theory doi:10.1007/s11049-013-9209-5.

Bach, Emmon. 1986. The algebra of events. Linguistics and Philosophy 9: 5–16.

Bertinetto, Pier M. 1994. Statives, progressives and habituals. Linguistics 32: 391–423.

Bonomi, Andrea. 1997. The Progressive and the structure of events. Journal of Semantics 14: 173–205.

Borer, Hagit. 2005. Structuring sense. Vol. II. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Comrie, Bernard. 1976. Aspect: An introduction to the study of verbal aspect and related problems. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Deen, Kamil Ud. 1997. The interpretation of RIs in English. Is eventivity a factor? Ms. UCLA.

Demirdache, Hamida, and Myriam Uribe-Etxebarría. 2000. The primitives of temporal relations. In Step by step: Essays on minimalist syntax in honor of Howard Lasnik, ed. R. Martin, 157–186. Cambridge: MIT Press.

Demirdache, Hamida, and Myriam Uribe-Etxebarría. 2004. The syntax of time adverbs. In The syntax of time, eds. Jacqueline Guéron, and Jacqueline Lecarme, 217–234. Cambridge: MIT Press.

Demirdache, Hamida, and Myriam Uribe-Etxebarría. 2007. The syntax of time arguments. Lingua 117: 330–366.

Demirdache, Hamida, and Myriam Uribe-Etxebarría. 2014. Aspect and temporal anaphora. Natural Language & Linguistic Theory. doi:10.1007/s11049-014-9231-2.

Denison, David. 1993. English historical syntax. London/New York: Longman.

Dowty, David. 1979. Word meaning and Montague Grammar. Dordrecht: Reidel.

Ferreira, Marcelo. 2005. Event quantification and plurality. PhD. Dissertation, MIT.

Grice, Herbert. 1975. Logic and conversation. In Syntax and semantics 3: Speech acts, eds. P. Cole, and J. L. Morgan, 41–58. San Diego: Academic Press.

Hallman, Peter. 2009a. Proportions in time: Interactions of quantification and aspect. Natural Language Semantics 17.1: 29–61.

Hallman, Peter. 2009b. Instants and intervals in the event/state distinction. Ms. UCLA.

Hallman, Peter. 2013. Past tense is stative. Ms. University of Vienna.

Hoekstra, Teun, and Nina Hyams. 1998. Aspects of root infinitives. Lingua 106: 81–112.

Hoffmann, Thomas. 1966. Past tense replacement and the English modal auxiliary system. In Harvard computation laboratory report NSF-17. Cambridge: Harvard University.

Hyams, Nina. 2007a. Aspectual effects on interpretation in early grammar. Language Acquisition 14.3: 231–268.

Hyams, Nina. 2007b. Aspectual effects on interpretation in early grammar. Language Acquisition 14: 3.

Hyams, Nina. 2009. Missing subjects in early child language. In Handbook of language acquisition theory in generative grammar, eds. J. De Villiers, and T. Roeper. Dordrecht: Kluwer.

Kamp Hans, and Uwe Reyle. 1993. From discourse to logic. Dordrecht: Kluwer.

Klein, Wolfgang. 1994. Time in language. London: Routledge.

Klein, Wolfgang. 2009. How time is encoded. In The expression of time, eds. Wolfgang Klein and Ping Li, 39–82. Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter.

Lakoff, George. 1966. Stative verbs and adjectives in English. In Harvard computational laboratory report NSF-17. Cambridge: Harvard University.

Landman, Fred. 1992. The progressive. Natural Language Semantics 1: 1–32.

Moens, Marc, and Mark Steedman. 1988. Temporal ontology and temporal reference. Computational Linguistics 14(2): 15–28.

Parsons, Terence. 1990. Events in the semantics of English. Cambridge: MIT Press.

Portner, Paul. 2003. The temporal semantics and modal pragmatics of the perfect. Linguistics and Philosophy 26: 459–510.

Portner, Paul. 2011. Perfect and progressive. In Semantics: An international handbook of natural language meaning, eds. Claudia Maienborn, Klaus von Heusinger, and Paul Portner, 1217–1261. Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter.

Pratas, Fernanda. 2010. States and temporal interpretation in Capeverdean. In Romance languages and linguistic theory 2008—selected papers from ’Going Romance’ Groningen 2008, eds. Reineke Bok-Bennema, Brigitte Kampers-Manhe, and Bart Hollebrandse, 215–231. Amsterdam/Philadelphia: John Benjamins.

Pratas, Fernanda. 2011. Tense and aspect: Interactions in Capeverdean. Ms. Chronos 10, Ashton University. Birmingham, April.

Pratas, Fernanda. 2012. ‘I know the answer’: A perfect state in Capeverdean. In Romance languages and linguistic theory 2010—selected papers from ‘Going Romance 24’, eds. Irene Franco, Sara Lusini, and Andrés Saab, 65–86, Leiden, 2010. Amsterdam/Philadelphia: John Benjamins.

Pratas, Fernanda, and Nina Hyams. 2010. Introduction to the acquisition of finiteness in Capeverdean. In Language acquisition and development—proceedings of GALA 2009, eds. João Costa, Ana Castro, Maria Lobo, and Fernanda Pratas, 378–390. Cambridge: Cambridge Scholars Press.

Rothstein, Susan. 2004. Structuring events: An essay on the semantics of lexical aspect. Oxford: Blackwell.

Smith, Carlota. 1991. The parameter of aspect. Dordrecht: Kluwer.

Smith, Carlota. 2005. Aspectual entities and tense in discourse. Studies in Natural Language and Linguistic Theory 62: 223–238.

Stowell, Timothy A. 1993. Syntax of tense. Ms., University of California, Los Angeles.

Stowell, Timothy A. 2007. Sequence of perfect. In Recent advances in the syntax and semantics of tense, mood and aspect, eds. Louis de Saussure, Jacque Moeschler, and Genoveva Puskas, 123–146. Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter.

Taylor, Barry. 1977. Tense and continuity. Linguistics and Philosophy 1: 199–220.

ter Meulen, Alice. 1995. Representing time in natural language: The dynamic interpretation of tense and aspect. Cambridge: MIT Press.

Torrence, Harold, and Nina Hyams. 2004. On the role of aspect in determining finiteness and temporal interpretation in early grammar. In Proceedings of GALA 2003. Utrecht: LOT.

Verkuyl, Henk. 1999. Events as dividuals: Aspectual composition and event semantics. In Speaking of events, eds. J. Higginbotham, F. Pianesi, and A. Varzi, 169–205. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Vlach, Frank. 1981. The semantics of the progressive. In Syntax and semantics 14: Tense and aspect, ed. P. Tedeschi. New York: Academic Press.

Zagona, Karen. 1990. Times as temporal argument structure. Ms., University of Washington, Seattle.

Acknowledgements

I am deeply grateful to my Capeverdean consultants in Cape Verde and to all the children and child carers in the kindergartens of Cova da Moura, Lisbon. I also want to thank Hamida Demirdache, for our long and enthusiastic discussions on these Capeverdean data, the audiences at Chronos 10, in Birmingham, and at the TMEI conference, in the Azores, both in the Spring of 2011, and, finally, Nina Hyams, for her patience with the revision of my English and for her insightful comments and suggestions. As always, however, all errors are my responsibility. Research for this paper has been partly funded by the project ‘Events and subevents in Capeverdean’ (PTDC/CLE-LIN/103334/2008).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Pratas, F. The Perfective, the Progressive and the (dis)closure of situations: comment on the paper by María J. Arche. Nat Lang Linguist Theory 32, 833–853 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11049-014-9236-x

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11049-014-9236-x