Abstract

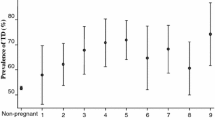

The negative health consequences of tobacco use are well documented. Some research finds women receiving abortions are at increased risk of subsequent tobacco use. This literature has methodological problems, most importantly, inappropriate comparison groups. This study uses data from the Turnaway Study, a longitudinal study of women who all sought, but did not all receive, abortions at 30 facilities across the United States. Participants included women presenting just before an abortion facility’s gestational age limit who received abortions (Near Limit Abortion Group, n = 452), just after the gestational limit who were denied abortions (Turnaways, n = 231), and who received first trimester abortions (First Trimester Abortion Group, n = 273). This study examined the association between receiving versus being denied an abortion and subsequent tobacco use over 2-years. Trajectories of tobacco use over 2 years were compared using multivariate mixed effects regression. Women receiving abortion maintained their level of tobacco use over 2 years. Women denied abortion initially had lower levels of tobacco use than women receiving abortion, but increased their tobacco use from 1 week through 12–18 months post-abortion seeking and then decreased their use by 2 years post-abortion seeking. Baseline parity modified these associations. Receiving an abortion was not associated with an increase in tobacco use over time. Overall, women who carry unwanted pregnancies to term appear to demonstrate similar cessation and resumption patterns to other pregnant women.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

USDHHS. (2001). Women and smoking: A report of the surgeon general. Atlanta, GA: Office on Smoking and Health.

Blizzard, L., Ponsonby, A. L., Dwyer, T., et al. (2003). Parental smoking and infant respiratory infection: How important is not smoking in the same room with the baby? American Journal of Public Health, 93(3), 482–488.

Ladomenou, F., Kafatos, A., & Galanakis, E. (2009). Environmental tobacco smoke exposure as a risk factor for infections in infancy. Acta Paediatrica, 98(7), 1137–1141.

Liebrechts-Akkerman, G., Lao, O., Liu, F., et al. (2011). Postnatal parental smoking: An important risk factor for SIDS. European Journal of Pediatrics, 170(10), 1281–1291.

Tong, V. T., Jones, J. R., Dietz, P. M., et al. (2009). Trends in smoking before, during, and after pregnancy: Pregnancy Risk Assessment Monitoring System (PRAMS), United States, 31 sites, 2000–2005. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, 58(SS04), 1–29.

Lelong, N., Kaminski, M., Saurel-Cubizolles, M. J., et al. (2001). Postpartum return to smoking among usual smokers who quit during pregnancy. The European Journal of Public Health, 11(3), 334–339.

Kahn, R. S., Certain, L., & Whitaker, R. C. (2002). A reexamination of smoking before, during, and after pregnancy. American Journal of Public Health, 92(11), 1801–1808.

Carmichael, S. L., & Ahluwalia, I. B. (2000). Correlates of postpartum smoking relapse: Results from the Pregnancy Risk Assessment Monitoring System (PRAMS). American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 19(3), 193–196.

Colman, G. J., & Joyce, T. (2003). Trends in smoking before, during, and after pregnancy in ten states. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 24(1), 29–35.

Fingerhut, L. A., Kleinman, J. C., & Kendrick, J. S. (1990). Smoking before, during, and after pregnancy. American Journal of Public Health, 80(5), 541–544.

Solomon, L., & Quinn, V. (2004). Spontaneous quitting: Self-initiated smoking cessation in early pregnancy. Nicotine & Tobacco Research, 6(Suppl 2), S203–S216.

Park, E. R., Chang, Y., Quinn, V., et al. (2009). The association of depressive, anxiety, and stress symptoms and postpartum relapse to smoking: A longitudinal study. Nicotine & Tobacco Research, 11(6), 707–714. doi:10.1093/ntr/ntp053.

Allen, A. M., Prince, C. B., & Dietz, P. M. (2009). Postpartum depressive symptoms and smoking relapse. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 36(1), 9–12.

O’Campo, P., Faden, R. R., Brown, H., et al. (1992). The impact of pregnancy on women’s prenatal and postpartum smoking behavior. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 8(1), 8–13.

Coleman, P. K., Maxey, C. D., Spence, M., et al. (2009). Predictors and correlates of abortion in the fragile families and well-being study: Paternal behavior, substance use, and partner violence. International Journal of Mental Health and Addiction, 7, 405–422.

Roberts, S. C., Avalos, L. A., Sinkford, D., et al. (2012). Alcohol, tobacco and drug use as reasons for abortion. Alcohol and Alcoholism, 47(6), 640–648. doi:10.1093/alcalc/ags095.

Kullander, S., & Kallen, B. (1971). A prospective study of smoking and pregnancy. Acta Obstetricia et Gynecologica Scandinavica, 50, 83–94.

Coleman, P. K., Reardon, D. C., & Cougle, J. R. (2005). Substance use among pregnant women in the context of previous reproductive loss and desire for current pregnancy. British Journal of Health Psychology, 10(Pt 2), 255–268.

Pedersen, W. (2007). Childbirth, abortion and subsequent substance use in young women: A population-based longitudinal study. Addiction, 102(12), 1971–1978.

Olsson, C. A., Horwill, E., Moore, E., et al. (2014). Social and emotional adjustment following early pregnancy in young Australian women: A comparison of those who terminate, miscarry, or complete pregnancy. Journal of Adolescent Health, 54(6), 698–703.

Coleman, P. K., Reardon, D. C., Rue, V. M., et al. (2002). A history of induced abortion in relation to substance use during subsequent pregnancies carried to term. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology, 187(6), 1673–1678.

Reardon, D. C., Coleman, P. K., & Cougle, J. R. (2004). Substance use associated with unintended pregnancy outcomes in the National Longitudinal Survey of Youth. The American Journal of Drug and Alcohol Abuse, 30(2), 369–383.

Dingle, K., Alati, R., Clavarino, A., et al. (2008). Pregnancy loss and psychiatric disorders in young women: An Australian birth cohort study. The British Journal of Psychiatry, 193(6), 455–460.

Upadhyay, U. D., Weitz, T. A., Jones, R. K., et al. (2013). Denial of abortion because of provider gestational age limits in the United States. American Journal of Public Health. doi:10.2105/AJPH.2013.301378.

Rocca, C., Kimport, K., Gould, H., et al. (2013). Women’s emotional responses to unintended pregnancy, abortion and being denied an abortion in the United States. Perspectives on Sexual and Reproductive Health, 45(3), 122–131.

Dobkin, L., Gould, H., Barar, R., et al. (2014). Implementing a prospective study of women seeking abortion in the United States: Understanding and overcoming barriers to recruitment. Women’s Health Issues, 24(1), e115–e123.

Pazol, K., Zane, S., Parker, W. Y., et al. (2011). Abortion surveillance—United States, 2007. MMWR, 60(1), 1–42.

Gould, H., Perrucci, A., Barar, R., et al. (2012). Patient education and emotional support practices in abortion care facilities in the United States. Women’s Health Issues, 22(4), e359–e364.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2008). Smoking prevalence among women of reproductive age—United States, 2006. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, 57(31), 849–852.

Altfeld, S., Handler, A., Burton, D., et al. (1997). Wantedness of pregnancy and prenatal health behaviors. Women and Health, 26(4), 29–43.

Gipson, J. D., Koenig, M. A., & Hindin, M. J. (2008). The effects of unintended pregnancy on infant, child, and parental health: A review of the literature. Studies in Family Planning, 39(1), 18–38.

Little, R. J. A., & Rubin, D. B. (2002). Statistical analysis with missing data (2nd ed.). Hoboken, NJ: Wiley.

Morton, L. M., Cahill, J., & Hartge, P. (2006). Reporting participation in epidemiologic studies: A survey of practice. American Journal of Epidemiology, 163(3), 197–203.

Galea, S., & Tracy, M. (2007). Participation rates in epidemiologic studies. Annals of Epidemiology, 17(9), 643–653.

Acknowledgments

Components of this study were funded by the Wallace Alexander Gerbode Foundation, the William and Flora Hewlett Foundation, the David and Lucile Packard Foundation, and an anonymous foundation. The authors thank Rana Barar, Heather Gould and Sandy Stonesifer for study coordination and management; Janine Carpenter, Undine Darney, Ivette Gomez, Selena Phipps, Claire Schreiber and Danielle Sinkford for conducting interviews; Michaela Ferrari and Elisette Weiss for project support; and Jay Fraser, John Neuhaus, and Caitlin Gerdts for database and statistical assistance. Preliminary findings from this study were presented at the American Public Health Association Conference in San Francisco, CA in October 2012.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Roberts, S.C.M., Foster, D.G. Receiving Versus Being Denied an Abortion and Subsequent Tobacco Use. Matern Child Health J 19, 438–446 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10995-014-1515-y

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10995-014-1515-y