Abstract

The importance of land use in affecting a range of ecosystem services (ES) provided from rural landscapes is increasingly recognised, creating an imperative for tools to assist in managing impacts of land use on ES provision. Many stakeholders, at a range of scales, are involved, including policy makers and implementers, land users and people receiving the services. Here, we develop a new and comprehensive typology of ES maps by expanding the basic stock-flow-receptor concept to create a set of map categories that embraces requirements for management of ES provision. We then use this typology as a framework for assessment of approaches to mapping ES. Most approaches have considered natural capital stocks of few services, at large scales (>1,000 km2) and coarse resolution (>100 m2). Emphasis has been on areas of ES generation, with little attention to flows, limiting the extent to which reception of services, interactions amongst services, and impacts on different stakeholders are considered. Most approaches focused on a bounded watershed or administrative unit, with little attention to landscape evolution, or to the definition of system boundaries that encompass flows from source to reception for different services. Although uncertainty is inherent in both input data and the services that are mapped, this is rarely acknowledged, quantified or presented. These features of current mapping approaches constrain their usefulness for informing the management of ES provision from rural landscapes. Key areas for future development are (1) maps at scales and resolutions that connect field scale management options to local landscape impacts; (2) mapping flows, and defining landscape boundaries, that include complete pathways, from source to reception; (3) calculating and presenting information on synergies and trade-offs amongst services; and (4) incorporating stakeholder knowledge and perspectives in the generation and interpretation of maps to bound and communicate uncertainty and improve their legitimacy.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Ecosystem services (ES) are the benefits that people derive from ecosystems (MA 2005) and it is becoming widely recognised that rural land use affects the provision of a range of ES, generated and received by different stakeholders, creating concerns about the balance of their supply and demand (Crossman et al. 2013). Whilst an ES approach has now been widely accepted as a useful framework to guide policy (Fisher et al. 2008) the concept has yet to be structurally integrated within environmental planning and management (Cowling et al. 2008a; Daily et al. 2009; Groot et al. 2010). There is an increasingly important imperative to close the implementation gap between theory and practice (Cook and Spray 2012).

Changes to ES provision globally, are strongly associated with change in land use, particularly the widespread conversion of natural ecosystems to agroecosystems (Bruinsma 2003; MA 2005). Much of the opportunity for improving ES provision now rests in specifically managing farmland, forests and woodland. Often, changes on the ground are made by farmers, acting autonomously or in circumstances where their decisions are influenced by policy, either through regulations or incentives, particularly payments for environmental services (PES) and certification schemes (Wynne-Jones 2013). Given the requirement for interdisciplinary and participatory approaches envisioned by an ES approach (Cowling et al. 2008b), maps provide an intuitive, visual means of communicating information amongst stakeholders. For an ES approach to influence rural land use, there is a need for mapping tools that operate at scales fine enough to incorporate impacts of alternative land management options at field and farm scales on the livelihoods of land users, at the same time as showing impacts on ES that can manifest at larger landscape scales. This cross-scale integration is a minimum requirement for enabling land users to take into consideration the broad spectrum of ES potentially affected by their management decisions, as well as for guiding the implementation of agri-environmental policy at the scale at which land use change occurs. Tools that map ES provision need to represent where services are generated and how they then flow across landscapes to where they are received Reviews of mapping tools and approaches to date have either focussed only on their supply (Martinez-Harms and Balvanera 2012), on the indicators used to map services (Egoh et al. 2012) or with a view to standardising methods and models used or how they are reported (Seppelta et al. 2012; Crossman et al. 2013).

In policy contexts, where different agencies have responsibility for different land uses (e.g. forestry and agriculture) and ES (e.g. water regulation, biodiversity conservation and production), the mapping of ES could facilitate the cross-sector collaboration required for joined up decision making at the range of scales necessary to manage ES provision (Groot et al. 2010; Pettit et al. 2011). This is increasingly acknowledged, and a number of studies have suggested the need for more spatially explicit ES typologies (see Boumans and Costanza 2007; Fisher et al. 2009) but methods for doing this based on mapping of ES flows are still in their infancy (Morse-Jones et al. 2011).

Our present research aims to develop a typology of maps required to inform the management of ES provision from rural landscapes, by expanding the stock-flow-receptor model of Haines-Young and Potschin (2009). The expansion encompasses maps required to evaluate historical, current and future options of ES flows, in relation to the various stakeholders involved. The resulting typology is then used as a framework to assess published approaches to mapping ES in terms of their usefulness for managing ES provision. The results are interpreted in relation to how current approaches to mapping constrain their use for managing ES provision and suggestions are made for future developments to fill these implementation gaps.

Methods

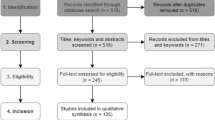

A set of published articles was assembled from an ISI Web of Knowledge search using the search string:(‘spatial’ or ‘mapping’ or ‘spatial modelling’ or ‘visualisation’) and ‘ecosystem services’. Given its prevalence within policy documents and its high profile, the Millennium Ecosystem Assessment (2005), provided the baseline classification of ES and nomenclature that we use in the present assessment. The assessment was confined to articles produced after the publication of the Millennium Ecosystem Assessment, that is, between January 2005 and July 2011 (when the search was processed). The initial search returned 207 articles covering both terrestrial and marine ecosystems. From this list, articles were retained that contained maps that could be used to inform decisions about management of ES generated in rural landscapes, that is, they fell into one of the categories in the ES map typology that was developed (see below). Where appropriate, other maps cited in these articles were also accessed and added to the set evaluated. Where more than one article was linked to the same location, the articles were grouped together as one case (e.g., Egoh et al. 2008, 2009, 2011). This resulted in a final set of 50 cases (Table 1) that were evaluated against the typology and associated dimensions of scale, resolution, number and types of ES, uncertainty and stakeholder engagement.

Map typology and framework for assessment of mapping approaches

A typology of ES maps was created by expanding the stock-flow-receptor model of Haines-Young and Potschin (2009), to encompass an evaluation of historical, current and future options of ES provision, in relation to the various stakeholders involved. The typology was developed by logical expansion of map categories to include the types of map needed to inform management of ES from rural landscapes as shown below. The typology was then applied across the selected set of 50 cases from the literature, to evaluate the relevance of maps produced for planning and managing ES generated in rural areas. The criteria used for evaluation were: the extent to which the maps were useful for local level decision makers determined by appropriate scale and resolution; which ecosystem services were considered; uncertainty; and, the usefulness of the maps for different stakeholders. The typology is fully presented in the results (Fig. 1) but the evaluation criteria and associated terminology used to organise and assess the maps, are further elaborated here.

Typology of mapped output for assessing ecosystem service provision, expanded from the stock-flow-receptor conceptual framework (shaded nodes) developed by Haines-Young and Potschin (2009). Unshaded nodes indicate forms of mapped output, filled arrows show major instances where one form of mapped output is used in the development of another and unfilled arrows show connections between the stock-flow-receptor framework and mapped output

Scale

The concept of a ‘landscape’ scale appears frequently in the ES literature (Schellhorn et al. 2008; Groot et al. 2010) but is often not defined (Jackson et al. 2007). We start from the premise that a landscape is a contiguous land area comprising a number of functional units such as woodlands, arable fields and wetlands, that may have different properties with respect to ES provision. It is a fluid concept that can be applied at a range of scales. Given the uncertainty associated the term ‘landscape’, we explore how the scale used in ES maps and the rationale given for defining system boundaries, enable us to refine our understanding of an operational concept of ‘landscape’ in the context of managing ES provision. We differentiate between three scales at which decision making about ES provision are likely to be made.

Local scale this is the scale at which ground level decisions about change in land use are made. The main actors at this scale are farmers, forest managers or other land users. It encompasses fields and farms up to an immediate landscape scale of 10–1,000 km2 at which ES initially manifest (e.g. sub-catchments or habitat networks), and may be managed, through farmer co-operatives or other collectives covering a contiguous land area. Maps generated at these scales are expected to allow farmers to see their land in a recognisable context and thus require fine resolution datasets.

Regional scale is defined here as the scale between local and national. This is the scale at which many policy decisions relating to ES provision are currently made and is generally over 1,000 km2 but sub-national. The resolution required to support regional decisions is generally quite coarse.

National scale is defined here as the scale at which strategic decisions about ES are made. This encompasses supranational transboundary contexts in some locations (e.g. some major lakes and protected area networks). Assessments at national scale tend to use aggregated national datasets, which are generally very coarse in their spatial resolution.

In practice, different landscape units can be defined for different purposes, such as watersheds, habitat networks or administrative districts and there will be different boundaries relevant to different ES and management units. Even though landscapes can be broken down hierarchically into smaller functional units, interactions amongst adjacent land uses, makes the process of scaling up non trivial (Costanza et al. 2002). Moving between scales requires some degree of simplification of spatial datasets (Seppelt et al. 2011).

Resolution

Land use datasets play a fundamental role in mapping ES. Resolution, refers to the amount of detail present in a dataset or map. Scientists have tended to use indicators, derived from land use or land cover as a proxy for the provision of ES (Marion 2009; Nelson et al. 2009). The ability to map, for example, tree cover in an area, may be used to infer water regulation. These relationships remain largely untested for most ES (Naidoo et al. 2008; Bennett et al. 2009). Despite this, mapping the areal extent and the position of these features, is fundamental for understanding their role in ES provision. The resolution of these data will have a significant impact on our ability to model ES provision. For example, datasets that identify individual trees and hedgerows, provide opportunities for much finer scale modelling of water flows than datasets that can only register large areas of woodland (Jackson et al. 2008). The evaluation of impacts of land use change on multiple ES simultaneously, requires integration of several spatially referenced datasets that may have different resolutions. In order to use maps in decision making the features have to be mapped at resolutions appropriate for the type of decision being made. Maps produced at national or regional scales may indicate where opportunities for changes in provision are required; but may offer only limited utility for ecosystem managers, who often require fine resolution information about how land use change will impact ES provision (Wynne-Jones 2013). The resolution of maps was assessed in our assessment by considering both the resolution of contributing datasets and that of the maps produced from them.

Type and number of ecosystem services

A fundamental requirement for adopting an ES approach to management is that a broad suite of ES are considered. The ability to map impacts of land use change on multiple ES simultaneously is a prerequisite for identification of synergies and trade-offs amongst them and hence for integrated planning. The extent to which the mapping approaches used in the 50 selected cases were able to accommodate requirements for integrated planning was assessed in terms of the types and number of ES mapped. The degree to which services were defined consistently across cases was also assessed because this has implications for comparative analysis (Haines-Young and Potschin 2011).

Uncertainty

ES provision is often embedded within complex, non-linear, multi-component systems, resulting in considerable uncertainty associated with scale-dependenci-es, scale–interactions and temporal dynamics represented on maps (Kremen and Ostfeld 2005). Lack of data is a key constraint for understanding ecosystem processes (Kremen and Ostfeld 2005; Carpenter et al. 2009) and proxies are often used to represent ES, despite reservations about their reliability at different scales (Eigenbrod et al. 2010a). The extent to which uncertainty was represented on maps was evaluated for each case by inspection of maps and the text relating to them.

Stakeholder engagement

ES are explicitly linked to human wellbeing (MA 2005) and their management at local scales, is likely to require interactions amongst multiple stakeholders, with potentially divergent knowledge systems and priorities (Fabricius et al. 2006; Vanclay et al. 2006). One way of addressing this issue is to explicitly incorporate local knowledge in ES assessments (Sinclair and Walker 1998; Cerdan et al. 2012). The extent to which local people had been involved in developing, validating and utilising maps was evaluated for each case by inspecting the methods and results sections to ascertain local involvement together with any information provided on map validation.

For the purposes of this assessment we recognise three broad stakeholder groups involved in ES management: ES providers, ES receivers, and intermediaries. These groupings are derived from the literature on payments for ES (Swallow et al. 2007). ES providers are defined here as entities (an individual, family, group, corporation or community) whose actions directly modify the quantity or quality of ES being generated, either positively or negatively. ES receivers are interested and affected parties who are impacted by the ES. Intermediaries are the diverse set of entities (including policy makers, non-governmental organizations, the scientific community and community organizations) that directly or indirectly shape interactions among ES providers, receivers, and the ecosystem itself. These groupings are not mutually exclusive, and it is entirely possible for an actor to belong to more than one group.

Results

A typology was developed that classified ES maps into 17 broad categories (the unshaded nodes in Fig. 1). This drew on various recent studies (Cowling et al. 2008b; Fisher et al. 2009; Groot et al. 2010; Morse-Jones et al. 2011) to augment the basic stock-flow-receptor model of Haines-Young and Potschin (2009). The types of maps are arranged sequentially creating a framework that shows how some maps are used in developing others. This framework incorporates a temporal dimension and explicitly explores where synergies and trade-offs amongst services can be mapped. It is explained below and then used to evaluate ES maps found in the collection of cases derived from published literature.

Types of map

The 17 types of map and the interactions amongst them are explained below, referring to the unshaded nodes in Fig. 1 by their alphanumeric coding.

Stocks of natural capital

At the place where ES are generated, the spatial arrangement, quantity and composition of functional units within a landscape have a strong influence on the ES generated (node 1A). As all landscapes exhibit some heterogeneity in their composition, understanding spatial variation in the location of similar types of functional unit is a key requirement for assessments of their capability to generate ES and for making decisions associated with their management. By associating features with ES, in situ values (node 1B) can be assigned, using, for example, benefit transfer approaches, where values are assigned to objects with specific characteristics and later used to assign values for objects with similar properties in other systems (see Troy and Wilson 2006; Lautenbach et al. 2011). Acknowledging the potential roles of keystone landscape features, for which a small change in areal extent can have large impacts on one or more ES, allows identification of hotspot and coldspot areas (node 1C). Synergies and trade-offs can exist amongst ES where they are generated (node 2B). For example, there are synergies where a functional unit is associated with the provision of multiple services, such as woodlands on marginal land providing a broad range of provisioning, regulating and cultural services, but trade-offs where, a wetland, provides multiple benefits for water quality and regulation, but limits agricultural productivity. These in situ valuations, focus solely on the place of generation and do not consider variation in reception.

Flows of ecosystem services

Ecosystem functions become ‘ecosystem services’ when humans benefit either directly or indirectly from them and so there is a need to map service flows from where they are generated to where they are received (node 2A). The area of effect associated with an ES may range from in situ benefits (such as the provision of shelter) that have no flow component, to benefits realised at a global scale (such as mitigation of climate change through increased carbon storage). Where flow pathways exist, the value of services may vary in relation to the location of recipients. As we move away from where the service was generated, the value received may be influenced by bio-physical factors, such as topography, or, social factors, such as variation in the number of uses and users of a service, and its scarcity or abundance within receptor populations (Morse-Jones et al. 2011; Crossman et al. 2013). There may also be interactions amongst ES along their flow pathways, and at the places where they are received, influenced by the medium of delivery. Potential water quality benefits delivered by woodlands, for example, may be diluted by inputs from intensive agriculture further downstream that breach a quality threshold. Explicitly identifying synergies and trade-offs amongst ES (node 2B) is fundamental to managing them for broader societal benefits. Once stocks, flow pathways, and, synergies or trade-offs amongst ES, have been identified, it is then possible to identify opportunities for interventions to improve ES provision (node 2C). This involves mapping the areas where modifying land use or cover has the greatest likelihood of impacting ES in relation to management objectives for a given landscape, taking into account impacts on services and stakeholders likely to be affected by the interventions.

Impacts

To link ecosystem functions and benefits to human wellbeing requires explicit acknowledgement of where the benefits of ES manifest (node 3A). Understanding the linkages between areas where ES are generated and where they are received is important for policy development, because, decisions by ‘upstream’ stakeholders to meet local requirements, may lead to positive or negative consequences from the perspective of ‘downstream’ stakeholders, at larger scales (Hein et al. 2006). Once receptor areas have been identified, then stakeholders who benefit (‘winners’) and those who either do not receive services (‘neutrals’) or who see a decrease in service supply (‘losers’) can be identified (node 3B). This approach facilitates needs analysis that can inform strategic decision making, often complicated because stakeholders may be winners within the context of some ES and losers with respect to others, especially when evaluated over long time horizons. For example, instances where unsustainable land use strategies provide short term benefits but degrade the system over the long term. The spatially explicit identification of winners and losers allows identification of strategies for equitable modification to ES provision (node 3C). This can be fed back into opportunity mapping (node 2C) to support an iterative decision making process. Finally, values (nodes 3D, 4C and 5D) can be assigned and mapped for past, present, future or alternative scenarios of ES provision. These values focus on the place of reception for beneficiaries and may differ from those arising from a focus on the place of generation and hence on providers (node 1B).

Time

Provision of ES is dynamic through time as well as space, so that developing a spatially explicit understanding of trends in ES supply is required for their management. Mapping the impacts of historic land use change helps to explain variation in current ES supply and may help identify interventions to address shortfalls in delivery where reversion of land use change is appropriate. Mapping both historic land cover (node 4A) and historic transformations (node 4B) can provide valuable insight into both current and future ES delivery (see Reyers et al. 2009 for an example) and feed into identification of opportunities for interventions (node 2C). In a similar way, consideration of future drivers of land use change (e.g. the effects of climate change) or exploration of alternative scenarios for land use, requires development of future or alternate land use maps (node 5A), that can be used to inform models of ES flows. These can then be used to map potential impacts (node 5B) both in terms of winners and losers (node 5C).

Evaluation of maps

In this section we evaluate the ES maps from the collection of 50 cases, in relation to the typology developed in the previous section.

Flow pathways

Only 8 % of cases mapped flows of ES (Gret-Regamey et al. 2008; Kozak et al. 2011; Simonit and Perrings 2011; Nedkov and Burkhard (2012). These involved ES with clear flow pathways, such as water or avalanches.

Whilst many cases mapped spatially distributed values for ES, they did not represent flows, or fully incorporate flow pathways in the calculation of values displayed (see Troy and Wilson 2006; Chen et al. 2009; Tallis and Polasky 2009; Swetnam et al. 2011). Where multiple ES were mapped, representing flow pathways became complex because a range of scales was often required to encompass all flows. The absence of flow mapping is a significant gap in current mapping methodologies and makes it difficult to evaluate interactions amongst ES as you move away from where they were generated. Frequently (32 % of cases) hotspots were mapped, showing functional units that deliver multiple benefits (Gimona and Horst 2007; Crossman and Bryan 2009; O’Farrell et al. 2010; Bai et al. 2011) but the maps were not explicit about where the benefits were manifest or who benefited.

Without flow pathways it is impossible to explicitly identify receptor areas (and thus winners and losers) associated with any change to ES provision. The exception to this is where the value of a service is realised in situ (Sherrouse et al. 2011). A number of cases used scenario approaches that showed changes in ES across a landscape, for example, using the InVEST tool (Nelson et al. 2009; Bai et al. 2011). They did not identify clear links to final recipients of the services, nor any form of needs analysis to identify where changes in provision were most desirable. The importance of developing appropriate methodologies to link service generation to receptors was demonstrated in Illinois where the value calculated for two wetlands ranged from around $28 thousand to $2.5 billion in one case and, from nearly $532 thousand to over $216 million in the other, depending on the spatial discounting method used (Kozak et al. 2011).

Similarly, less than 20 % of cases identified synergies and/or trade-offs amongst ES at locations beyond the area where they were generated. Most often, where they were considered at all, trade-offs were implicit in presentation of two or more maps that could be compared (Bai et al. 2011). Valuing or bundling ES at the point of generation was common (>30 % of cases), but may be misleading because receptor areas for each of the bundled services may be located far apart (Raudsepp-Hearne et al. 2010).

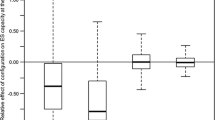

Scale and resolution

There was considerable variation in the scales used to map ES provision. Most cases (60 %) were at regional scales, that is >1,000 km2 but sub-national (Table 1). Only 8 % of cases produced output at local scales below 1,000 km2. The resolution of many datasets was not explicitly stated and for those cases where it was, several datasets of different resolution were often involved (Fig. 2). The finest resolution of datasets in more than 50 % of cases, for which it could be determined, were 100 m2 or coarser and only two cases were at 10 m2 or finer. The coarse resolution of these mapping approaches will limit their utility to ES providers, in terms of evaluating impacts of field scale interventions on ES provision.

Resolution of data used to map outputs from the cases (n = 49) reviewed in this article (see Table 1)

There was a five fold order of magnitude range in the size of units described as a landscape amongst cases (Fig. 3), with several mapping areas over one million hectares. A third of the studies focussed on national level ES provision and 6 % were international (Kienast et al. 2009; Luck et al. 2009; Maes et al. 2011). Only 4 % of cases incorporated nested approaches, mapping ES provision at a range of scales (Troy and Wilson 2006; O’Higgins et al. 2010a).

Area of mapped units (ha) described as being at a landscape scale in local (grey bars) and regional (black bars) cases (n = 34) reviewed in this article (see Table 1). Some cases included mapped units of more than one size

Looking across the 50 cases, it was evident that what constitutes a functional unit for the supply of ES was determined partially by the requirements of the observer and partially by the resolution with which the landscape was observed. These considerations can have a strong influence on how landscape functions are perceived and measured. For example, woodland blocks were a frequently encountered functional unit, where the assemblage of organisms (trees and associated biota) combined to provide a distinct set of services which differed from those of neighbouring functional units (such as arable fields). For carbon sequestration it is relatively straightforward to distinguish between functional units such as woodland blocks and arable fields, with respect to their time-averaged carbon storage. However, finer resolution features, like individual trees and hedgerows also sequester carbon, in varying amounts but they are generally too small in extent to be represented individually in land cover datasets. As a result, the isolated tree and linear hedgerow features, are not often mapped and their collective impact is not taken into consideration, although it may be significant when aggregated at a landscape scale. Where decisions are being made at scales at which these features make a significant impact, then there is a clear requirement for the resolution of datasets to be high enough to represent them. It was difficult to determine the resolution for most datasets in the literature as they were seldom stated and often, different layers were mapped at different resolutions, making the interpretation of merged datasets problematic (Chen et al. 2009).

In all cases a single boundary was used to define the extent of ES delivery and in most, with the exception of those exploring flood risk and water regulation, ‘catchment areas’ that encompassed the entire flow of services from source to reception were not defined. In most cases, maps used socio-political boundaries or water catchment boundaries, despite some of the ES that were mapped not being associated with either water or received within the administrative boundary used (see, for example, Bai et al. 2011). Whilst this was clearly pragmatic from a governance or management perspective for ES supply, it does not permit understanding of all ES equally. For example, appropriate boundaries for a habitat network, necessary to understand biodiversity conservation, a farmer co-operative, important from a livelihood and management perspective, and a stream catchment, may all differ, but each is important for understanding how land use change may impact the ES in question.

Type and number of ecosystem services

There was a large range in the number of ES mapped (from 1 to 31) for each case (Fig. 5). More than 50 % of cases mapped four or fewer services, with a mode of three. Cases that mapped only a few ES were less useful for managing ES provision than more comprehensive approaches because of interactions amongst services (Everard 2009). Many of the maps were showing ES generation rather than provision but, even where some recipients were clearly identified, such as those affected by increased flood risk (Nedkov and Burkhard 2012; Batker et al. 2010), approaches were not comprehensive in terms of considering winners and losers. So, while it was relatively easy to document stakeholders who had been flooded, there were no attempts to identify potential beneficiaries of floods, such as owners or users of farmland receiving nutrients from seasonal flooding. The 8 % of cases with the most comprehensive mapping of ES provision, used participatory mapping approaches based on interviews with local stakeholders (Raymond et al. 2009; Bryan et al. 2010; Maynard et al. 2010; Bryan et al. 2011a). These were all large regional scale studies from Australia.

The most commonly mapped services were regulating and provisioning services (Fig. 4). Supporting services were not mapped, except in the Australian participatory mapping cases mentioned above. There was considerable inconsistency in how ES were defined and classified amongst cases. Whilst many articles referenced the MA (2005), many of them used classifications that ignored, expanded or heavily modified the MA categorisation. A number of cases created composite services that combined two or more MA services under one metric, for example, cultural value (Troy and Wilson 2006; Liu et al. 2010) or regulation (Sherrouse et al. 2011). Figure 5 gives an indication of the number of ES mapped against the MA classification, but in many instances the mapped categories did not directly correspond to the MA classes, for example, farmer livelihood and energy production (Metzger et al. 2006) or extraction of raw materials from marine organisms (Ruiz-Frau et al. 2011) and so could not be counted. Conversely, for other ES, the MA uses broad categories, such as climate regulation, whereas many of the maps reviewed here, showed constituent elements of climate regulation such as carbon sequestration.

Only 8 % of cases identified temporal variation in ES provision (Burkhard et al. 2010; He et al. 2011; Bateman et al. 2011; Zhang et al. 2011) and a mere 2 % mapped historic land disturbance in relation to impacts on current ES provision (Reyers et al. 2009). Lack of consideration of the historical context within which ES are currently evaluated ignores the evolution of landscape structure and function and may constrain decisions about ES management. Farmers, for example, often understand impacts of land use change on ES provision through having observed changes in their landscape over time, such as flashiness of streams and rivers associated with increasing stocking densities in upland pastures (Sinclair and Pagella, in review).

Uncertainty

Uncertainty was handled in a variety of ways in the 50 cases. In 2 % of cases it was the principal focus (Kozak et al. 2011), but more often, maps were presented with no acknowledgement of underlying uncertainty. In 4 % of cases where alternate scenarios were presented, some uncertainly was implicit (Wang et al. 2009; Bateman et al. 2011). While not addressed visually, uncertainty was explicitly discussed in relation to underlying data in 6 % of cases (Metzger et al. 2006; Liu et al. 2010; Willemen et al. 2010) but largely ignored in others. Perhaps surprisingly, given that the ES paradigm is essentially anthropocentric, there were no cases that drew explicitly on local knowledge to ground proof maps, although 6 % of cases did look at stakeholder values associated with areas of ES provision (Raymond et al. 2009; Pettit et al. 2011; Sherrouse et al. 2011).

Stakeholder engagement

Only 10 % of cases encompassed direct interaction with stakeholders (Raymond et al. 2009; Maynard et al. 2010; Swetnam et al. 2011; Ruiz-Frau et al. 2011; Bryan et al. 2011b). For these, the methods used to select stakeholders were not clear but they did not include ES providers, such as farmers, living in areas associated with ES generation, nor stakeholders explicitly identified as recipients. Intermediaries were documented in 10 % of cases.

Discussion

A new and comprehensive typology of ES maps was presented and proved useful as the framework for the assessment of approaches to mapping ES from rural landscapes in relation to their management. This revealed that mapping approaches so far published have emphasised natural capital stocks of few services (mode of three), at large scales (>1,000 km2) and coarse resolution (>100 m2).

Often, the emphasis has been on areas of ES generation with little attention paid to flow pathways, severely limiting the extent to which reception of services, interactions amongst services, and impacts on different stakeholders are considered. The ARIES toolkitFootnote 1 is described as being capable of mapping flows, but this capacity was not demonstrated in the published output that we evaluated. The need to balance supply and demand for ES has recently been highlighted (Crossman et al. 2013). In practice, ES are only ‘provided’, when they benefit stakeholders (Hein et al. 2006), and so, without tracking services from their source through to their reception, it is not possible to fully evaluate them. It is dangerous to assume that ES are primarily received close to their source, or only in relation to topographical routing. For example, protein produced in rural landscapes in Wales is primarily exported (80 % of livestock products enter international trade) and vast quantities of water (equivalent to the daily requirement of the entire Welsh population) are extracted and transported through canal systems to provide water for Birmingham in England (Russell et al. 2011).

In general, approaches to ES mapping focused on the present and possible future states of ES generation from a bounded watershed or administrative unit. There is increasing interest in the cultural heritage associated with landscapes, as embodied in the principles enshrined in the European Landscape Convention (Council of Europe 2000). In many cases, it is likely to be important to place current options for managing ES provision within the context of the past evolution of ecosystem function, both to understand the likely future impact of options, and to be cognisant of landscape heritage. There is clearly scope for the use of trend analyses and dynamic visualisations to augment what can be achieved with static maps, particularly given the increasing availability of satellite land cover data (Burkhard et al. 2012).

Although considerable uncertainty is inherent in both input data and mapped output, this is rarely acknowledged, quantified or presented on maps. Given the widely acknowledged gaps in data about ecosystem processes, the degree to which maps present uncertainty is an important consideration. There is an increasing requirement for explicit acknowledgement and communication of uncertainty when negotiating land use management (Morss et al. 2005).

The features of current mapping approaches highlighted above, constrain their utility for informing the management of ES provision from rural landscapes. The four major gaps between what current mapping approaches are able to do and what is required to inform the management of ES provision are elaborated below.

Connecting land management decisions to impacts on ecosystem service generation

Mapping is fundamental to ES management and implementation of policy that promotes it, but our evaluation has shown that current approaches to producing maps are not at an appropriate scale and resolution to relate field level management decisions to impacts on ES at the local landscape scales at which they first manifest and can, therefore, be managed. This is a major gap in allowing farmers and other land managers to comprehend the impact of their decisions on ES provision. It equally constrains policy makers and implementers from assessing the value of different land management options for meeting objectives in ES generation and hence rewarding desirable management action. What is required are approaches that map landscapes with resolutions fine enough to capture field scale land management options that affect ES generation (circa 10 m) while representing their aggregate impact at local landscape scales of 10–1,000 km2.

Mapping flow pathways and boundary definition

The management of ES provision implies consideration of service flows from their source to where they are received but most approaches only consider the source area and essentially map the value of its natural capital stock without explicit consideration of flows. This engenders three major limits to the extent to which maps are useful for management, relating to: interactions amongst ES, stakeholder engagement and, boundary definition. A more comprehensive mapping approach would start by defining boundaries based upon significant flows for each service of interest. The boundaries for different services may differ (for example watersheds, habitat networks and administrative units), drawing in different receiving stakeholders some of whom may be remote from the source landscape. Even if the focus remains on the contribution of the source landscape to ES provision, this can be seen and evaluated in the broader context within which ES provision occurs, including the consideration of interactions amongst services, and management interventions, along flow pathways.

Trade-offs and synergies amongst ecosystem services

A feature of most management interventions that affect ES provision from rural landscapes, such as changes in land use, is that they will affect multiple services simultaneously and, therefore, their management requires consideration of synergies and trade-offs amongst these impacts. Few mapping approaches have gone much beyond presenting a series maps for the services of interest. Sometimes services are bundled at source, but this may obscure the effect of management options if the bundled services have different flow pathways. A more comprehensive approach would consider impacts of interventions along flow pathways for each service and then present an analysis of synergies and trade-offs amongst them.

Stakeholder engagement

Mapping approaches rarely incorporated knowledge or perspectives from the three principal stakeholder groups involved in ES management: ES providers, ES receivers and intermediaries. Where stakeholders were involved, the focus was on intermediaries. Lack of information about stakeholder preferences and priorities constrains development of targeted management strategies for ES provision and misses opportunities to engage ES providers in groundtruthing data and negotiating land management to meet ES management objectives. Given the utilitarian nature of ES there needs to be clear identification of where beneficiaries are in relation to service provision and also where services are not reaching intended recipients, to balance supply and demand (Crossman et al. 2013). It is also likely that many stakeholders are not fully aware of the role their environment is playing in their own well-being. This makes it critical for spatial tools to cater for non-expert engagement with their output. The outputs produced need to be understood by a range of different stakeholders so that they facilitate exchange of information. There is a legitimate tension emerging between attempts to standardise ES classification and nomenclature to facilitate comparative analysis across contexts (Haines-Young and Potschin 2011; Seppelta et al. 2012; Crossman et al. 2013) and more flexible approaches to local definition of ES by stakeholders to facilitate their management at local scales (Sinclair and Pagella, in review). Overall, there is clearly scope for greater stakeholder engagement in the generation and interpretation of ES maps. Involving stakeholders right at the outset through groundtruthing land cover and other baseline datasets assists both in bounding and communicating uncertainty, as well as, creating greater local legitimacy for ES maps and hence the management interventions developed from them.

Conclusion

A new and comprehensive typology of ES maps, developed by logical expansion of the basic stock-flow-receptor concept, resulted in a set of map categories and interactions that embraces requirements for management of ES provision from rural landscapes. The typology was a useful framework for assessing published approaches to mapping ES in relation to their fitness for supporting ES management in a multi-stakeholder context. The assessment revealed that in general, maps of natural capital stocks rather than ES flows were produced, most often for few services (mode of three), at large scales (>1,000 km2) and coarse resolution (>100 m2). The scant attention to mapping flows of ES limits the extent to which reception of services, interactions amongst services, and impacts on different stakeholders can be considered. The approaches generally mapped a bounded watershed or administrative unit, with little attention to landscape evolution, or to the definition of system boundaries that encompass flows from source to reception for different ES. Although uncertainty was inherent in both input data and the approaches to estimating ES values, this was rarely acknowledged, quantified or presented. These features of current mapping approaches constrain their usefulness for supporting the management of ES provision. Key areas for future development are: (1) production of maps at scales and resolutions that connect field scale management options to local landscape impacts at which they can be collectively managed; (2) approaches to mapping flows, and defining landscape boundaries, that include complete pathways, from source to reception; (3) calculating and presenting information on synergies and trade-offs amongst services; and (4) incorporating stakeholder knowledge and perspectives in the generation and interpretation of maps.

References

Anderson BJ, Armsworth PR, Eigenbrod F, Thomas CD, Gillings S, Heinemeyer A, Roy DB, Gaston KJ (2009) Spatial covariance between biodiversity and other ecosystem service priorities. J Appl Ecol 46:888–896

Bai Y, Zhuang C, Ouyang Z, Zheng H, Jiang B (2011) Spatial characteristics between biodiversity and ecosystem services in a human-dominated watershed. Ecol Complex 8(2):177–183

Batker D, Kocian M, Lovell B, Harrison‐Cox J (2010) Flood protection and ecosystem services in the Chehalis river basin. 1121 Tacoma Avenue South Tacoma, WA 98402, Earth economics

Bateman IJ, Mace GM, Fezzi C, Atkinson G, Turner K (2011) Economic Analysis for Ecosystem Service Assessments. Environ Resour Econ 48(2):177–218

Beier CM, Patterson TM, Chapin FS (2008) Ecosystem services and emergent vulnerability in managed ecosystems: a geospatial decision-support tool. Ecosystems 11(6):923–938

Bennett EM, Peterson GD, Gordon LJ (2009) Understanding relationships among multiple ecosystem services. Ecol Lett 12:1394–1404

Birch JC, Newton AC, Alvarez Aquino C, Cantarello E, Echeverria C, Kitzberger T, Schiappacasse I, Garavito NT (2010) Cost-effectiveness of dryland forest restoration evaluated by spatial analysis of ecosystem services. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 107(50):21925–21930

Boumans R, Costanza R (2007) The multiscale integrated Earth systems model (MIMES): the dynamics, modeling and valuation of ecosystem services. In: Bers C, Petry D, Pahl-Wostl C, (eds) Global Assessments: Bridging Scales and Linking to Policy. Report on the joint TIAS-GWSP workshop held at the University of Maryland University College, Adelphi, USA, 10 and 11 May 2007. GWSP Issues in Global Water System Research, 2nd edn. GWSP IPO, Bonn, pp 104–108

Bruinsma JE (ed) (2003) World Agriculture: Towards 2015/2030, An FAO Perspective, 1st edn. Earthscan, London

Bryan BA, Raymond CM, Crossman ND, Macdonald DH (2010) Targeting the management of ecosystem services based on social values: where, what, and how? Landscape Urban Plan 97(2):111–122

Bryan BA, Raymond CM, Crossman ND, King D (2011a) Comparing spatially explicit ecological and social values for natural areas to identify effective conservation strategies. Conserv Biol 25(1):172–181

Bryan BA, Raymond CM, Crossman ND, King D (2011b) Comparing Spatially Explicit Ecological and Social Values for Natural Areas to Identify Effective Conservation Strategies; Comparación de Valores Ecológicos y Sociales Espacialmente Explícitos de Áreas Naturales para la Identificación de Estrategias de Conservación Efectivas. Conserv Biol 25(1):172–181

Burkhard B, Petrosillo I, Costanza R (2010) Ecosystem services—bridging ecology, economy and social sciences. Ecol Complex 7(3):257–259

Burkhard B, Kroll F, Nedkov S, Müller F (2012) Mapping ecosystem service supply, demand and budgets. Ecol Ind 21:17–29

Carpenter SR, Mooney HA, Agard J, Capistrano D, DeFries RS, Diaz S, Dietz T, Duraiappah AK, Oteng-Yeboah A, Pereira HM, Perrings C, Reid WV, Sarukhan J, Scholes RJ, Whyte A (2009) Science for managing ecosystem services: beyond the Millennium Ecosystem Assessment. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 106(5):1305–1312

Cerdan CR, Rebolledo MC, Soto G, Rapidel B, Sinclair FL (2012) Local knowledge of impacts of tree cover on ecosystem services in smallholder coffee production systems. Agric Syst 110:119–130

Chen NW, Li HC, Wang LH (2009) A GIS-based approach for mapping direct use value of ecosystem services at a county scale: management implications. Ecol Econ 68(11):2768–2776

Cook BR, Spray CJ (2012) Ecosystem services and integrated water resource management: different paths to the same end? J Environ Manage 109:93–100

Costanza R, Voinov A, Boumans R, Maxwell T, Villa F, Wainger L, Voinov H (2002) Integrated ecological economic modeling of the Patuxent River watershed, Maryland. Ecol Monogr 72(2):203–231

Council of Europe (2000) European landscape convention, Florence, 20th October, 2000. http://conventions.coe.int/Treaty/en/Treaties/Html/176.htm. Accessed 6 Mar 2013

Countryside Council for Wales (CCW) (2010) Sustaining ecosystem services for human well–being: mapping ecosystem services. CCW

Cowling RM, Egoh B, Knight AT, O’Farrell PJ, Reyers B, Rouget’ll M, Roux DJ, Welz A, Wilhelm-Rechman A (2008a) An operational model for mainstreaming ecosystem services for implementation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 105(28):9483–9488

Cowling RM, Egoh B, Knight AT, O’Farrell PJ, Reyers B, Rouget’ll M, Roux DJ, Welz A, Wilhelm-Rechman A (2008b) An operational model for mainstreaming ecosystem services for implementation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 105(28):9483–9488

Crossman ND, Bryan BA (2009) Identifying cost-effective hotspots for restoring natural capital and enhancing landscape multifunctionality. Ecol Econ 68(3):654–668

Crossman ND, Burkhard B, Nedkov S, Willemen L, Petz K, Palomo I, Drakou EG, Martín-Lopez B, McPhearson T, Boyanova K, Alkemade R, Egoh B, Dunbar MB, Maes J (2013) A blueprint for mapping and modelling ecosystem services. Ecosyst Serv 4:4–14

Daily GC, Polasky S, Goldstein J, Kareiva PM, Mooney HA, Pejchar L, Ricketts TH, Salzman J, Shallenberger R (2009) Ecosystem services in decision making: time to deliver. Front Ecol Environ 7(1):21–28

de Groot RS, Alkemade R, Braat L, Hein L, Willemen L (2010) Challenges in integrating the concept of ecosystem services and values in landscape planning, management and decision making. Ecol Complex 7(3):260–272

Ditt EH, Mourato S, Ghazoul J, Knight J (2010) Forest conversion and provision of ecosystem services in the Brazilian Atlantic Forest. Land Degrad Dev 21(6):591–603

Egoh B, Reyers B, Rouget M, Richardson DM, Le Maitre DC, van Jaarsveld AS (2008) Mapping ecosystem services for planning and management. Agric Ecosyst Environ 127(1–2):135–140

Egoh B, Reyers B, Rouget M, Bode M, Richardson DM (2009) Spatial congruence between biodiversity and ecosystem services in South Africa. Biol Conserv 142(3):553–562

Egoh BN, Reyers B, Rouget M, Richardson DM (2011) Identifying priority areas for ecosystem service management in South African grasslands. J Environ Manage 92(6):1642–1650

Egoh B, Drakou EG, Dunbar MB, Maes J, Willemen L (2012) Indicators for mapping ecosystem services: a review. Report EUR 25456 EN. Office of the European Union, Luxembourg

Eigenbrod F, Armsworth PR, Anderson BJ, Heinemeyer A, Gillings S, Roy DB, Thomas CD, Gaston KJ (2010a) Error propagation associated with benefits transfer-based mapping of ecosystem services. Biol Conserv 143(11):2487–2493

Eigenbrod F, Armsworth PR, Anderson BJ, Heinemeyer A, Gillings S, Roy DB, Thomas CD, Gaston KJ (2010b) The impact of proxy-based methods on mapping the distribution of ecosystem services. J Appl Ecol 47(2):377–385

Everard M (2009) Ecosystem services case studies Better regulation science programme. ISBN: 978-1-84911-042-6. Environment Agency, Rio House, Bristol

Fabricius C, Sholes R, Cundill G (2006) Mobilizing knowledge for integrated ecosystem assessments. In: Reid WV, Berkes F, Wilbanks T, Capistrano D (eds) Bridging scales and knowledge systems: concepts and applications in ecosystem assessment, 1st edn. Island Press, Washington, pp 165–182

Farewell TS, Truckell IG, Keay CA, Hallett SH (2011) The derivation and application of Soilscapes: soil and environmental datasets from the National Soil Resources Institute. NSRI, Cranfield University, Bedford

Fisher B, Turner K, Zylstra M, Brouwer R, Groot RD, Farber S, Ferraro P, Green R, Hadley D, Harlow J, Jefferiss P, Kirkby C, Morling P, Mowatt S, Naidoo R, Paavola J, Strassburg B, Yu D, Balmford A (2008) Ecosystem services and economic theory: integration for policy-relevant research. Ecol Appl 18(8):2050–2067

Fisher B, Turner RK, Morling P (2009) Defining and classifying ecosystem services for decision making. Ecol Econ 68(3):643–653

Gimona A, van der Horst D (2007) Mapping hotspots of multiple landscape functions: a case study on farmland afforestation in Scotland. Landscape Ecol 22(8):1255–1264

Gret-Regamey A, Bebi P, Bishop ID, Schmid WA (2008) Linking GIS-based models to value ecosystem services in an Alpine region. J Environ Manage 89(3):197–208

Haines-Young R, Potschin M (2009) The links between biodiversity, ecosystem services and human well-being. In: Raffaelli D, Frid C (eds) Ecosystem ecology: a new synthesis. BES ecological reviews series. CUP, Cambridge

Haines-Young R, Potschin M (2011) Common international classification of ecosystem services (CICES): 2011 Update. EEA/BSS/07/007. European Environment Agency

He Y, Chen Y, Tang H, Yao Y, Yang P, Chen Z (2011) Exploring spatial change and gravity center movement for ecosystem services value using a spatially explicit ecosystem services value index and gravity model. Environ Monit Assess 175(1–4):563–571

Hein L, van Koppen K, de Groot RS, van Ierland EC (2006) Spatial scales, stakeholders and the valuation of ecosystem services. Ecol Econ 57(2):209–228

Jackson WJ, Maginnis S, Sengupta S (2007) Planning at a Landscape Scale. In: Scherr SJ, Mcneely JA (eds) Farming with Nature. The science and practice of Ecoagriculture. Island Press, Washington DC, pp 308–321

Jackson BM, Wheater HS, McIntyre NR, Chell J, Francis OJ, Frogbrook Z, Marshall M, Reynolds B, Solloway I (2008) The impact of upland land management on flooding: Insights from a multi-scale experimental and modelling programme. J Flood Risk Manage 1(2):71–80

Kienast F, Bolliger J, Potschin M, de Groot RS, Verburg PH, Heller I, Wascher D, Haines-Young R (2009) Assessing landscape functions with broad-scale environmental data: insights gained from a prototype development for Europe. Environ Manage 44(6):1099–1120

Klug H, Jenewein P (2010) Spatial modelling of agrarian subsidy payments as an input for evaluating changes of ecosystem services. Ecol Complex 7(3):368–377

Kozak J, Lant C, Shaikh S, Wang G (2011) The geography of ecosystem service value: the case of the Des Plaines and cache river wetlands, Illinois. Appl Geogr 31(1):303–311

Kremen C, Ostfeld RS (2005) A call to ecologists: measuring, analyzing, and managing ecosystem services. Front Ecol Environ 3(10):540–548

Krishnaswamy J, Bawa KS, Ganeshaiah KN, Kiran MC (2009) Quantifying and mapping biodiversity and ecosystem services: utility of a multi-season NDVI based Mahalanobis distance surrogate. Remote Sens Environ 113(4):857–867

Lautenbach S, Kugel C, Lausch A, Seppelt R (2011) Analysis of historic changes in regional ecosystem service provisioning using land use data. Ecol Indic 11(2):676–687

Lavorel S, Grigulis K, Lamarque P, Colace M, Garden D, Girel J, Pellet G, Douzet R (2011) Using plant functional traits to understand the landscape distribution of multiple ecosystem services. J Ecol 99(1):135–147

Liu S, Costanza R, Troy A, D’Aagostino J, Mates W (2010) Valuing New Jersey’s ecosystem services and natural capital: a spatially explicit benefit transfer approach. Environ Manage 45(6):1271–1285

Locatelli B, Imbach P, Vignola R, Metzger MJ, Leguía Hidalgo EJ (2011) Ecosystem services and hydroelectricity in Central America: modelling service flows with fuzzy logic and expert knowledge. Reg Environ Change 11:393–404

Lorz C, Fürst C, Galic Z, Matijasic D, Podrazky V, Potocic N, Simoncic P, Strauch M, Vacik H, Makeschin F (2010) GIS-based probability assessment of natural hazards in forested landscapes of central and south-eastern Europe. Environ Manag 46(6):920–930

Luck GW, Chan KMA, Fay JP (2009) Protecting ecosystem services and biodiversity in the world’s watersheds. Conserv Lett 2(4):179–188

MA (2005) Millennium ecosystem assessment synthesis report. 1st edn. Island Press, Washington, DC

Maes J, Paracchini ML, Zulian G (2011) A European Assessment of the Provision of Ecosystem Services: Towards an Atlas of Ecosystem Services. Scientific and Technical Research series—ISSN 1018-5593. Office of the European Union, Jerusalem

Marion P (2009) Land use and the state of the natural environment. Land Use Policy 26(1):S170–S177

Martınez-Harms MJ, Balvanera P (2012) Methods for mapping ecosystem service supply: a review. Int J Biodiversity Sci Ecosyst Serv Manage 8:17–25

Maynard S, James D, Davidson A (2010) The development of an ecosystem services framework for South East Queensland. Environ Manage 45(5):881–895

Mehaffey M, Van Remortel R, Smith E, Bruins R (2011) Developing a dataset to assess ecosystem services in the Midwest United States. Int J Geogr Inf Sci 25(4):681–695

Metzger MJ, Rounsevell MDA, Acosta-Michlik L, Leemans R, Schröter D (2006) The vulnerability of ecosystem services to land use change. Agric Ecosyst Environ 114(1):69–85

Morse-Jones S, Luisetti T, Turner RK, Fisher B (2011) Ecosystem valuation: some principles and a partial application. Environmetrics 22(5):675–685

Morss RE, Wilhelmi OV, Downtown MW, Gruntfest E (2005) Flood risk, uncertainty, and scientific information for decision making: lessons from and interdisciplinary project. Bull Am Meteorol Soc 85(11):1593–1601

Naidoo R, Ricketts TH (2006) Mapping the economic costs and benefits of conservation. Plos Biol 4(11):2153–2164

Naidoo R, Balmford A, Costanza R, Fisher B, Green RE, Lehner B, Malcolm TR, Ricketts TH (2008) Global mapping of ecosystem services and conservation priorities. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 105(28):9495–9500

Nedkov S, Burkhard B (2012) Flood regulating ecosystem services—Mapping supply and demand, in the Etropole municipality, Bulgaria. Ecol Indic 21:67–79

Nelson E, Mendoza G, Regetz J, Polasky S, Tallis H, Cameron DR, Chan KMA, Daily GC, Goldstein J, Kareiva PM, Lonsdorf E, Naidoo R, Ricketts TH, Shaw MR (2009) Modeling multiple ecosystem services, biodiversity conservation, commodity production, and tradeoffs at landscape scales. Front Ecol Environ 7(1):4–11

O’Farrell PJ, Reyers B, Le Maitre DC, Milton SJ, Egoh B, Maherry A, Colvin C, Atkinson D, De Lange W, Blignaut JN, Cowling RM (2010) Multi-functional landscapes in semi arid environments: implications for biodiversity and ecosystem services. Landscape Ecol 25(8):1231–1246

O’Higgins TG, Ferraro SP, Dantin DD, Jordan SJ, Chintala MM (2010a) Habitat scale mapping of fisheries ecosystem service values in estuaries. Ecol Soc 15(4):7

O’Higgins TG, Ferraro SP, Dantin DD, Jordan SJ, Chintala MM (2010b) Habitat scale mapping of fisheries ecosystem service values in estuaries. Ecol Soc 15(4):7

Pettit CJ, Raymond CM, Bryan BA, Lewis H (2011) Identifying strengths and weaknesses of landscape visualisation for effective communication of future alternatives. Landscape Urban Plan 100(3):231–241

Raudsepp-Hearne C, Peterson GD, Bennett EM (2010) Ecosystem service bundles for analyzing tradeoffs in diverse landscapes. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 107(11):5242–5247

Raymond CM, Bryan BA, MacDonald DH, Cast A, Strathearn S, Grandgirard A, Kalivas T (2009) Mapping community values for natural capital and ecosystem services. Ecol Econ 68(5):1301–1315

Reyers B, O’Farrell PJ, Cowling RM, Egoh BN, Le Maitre DC, Vlok JHJ (2009) Ecosystem services, land-cover change, and stakeholders: finding a sustainable foothold for a semiarid biodiversity hotspot. Ecol Soc 14(1):38

Ruiz-Frau A, Edwards-Jones G, Kaiser MJ (2011) Mapping stakeholder values for coastal zone management. Marine Ecol Prog Ser 434:239–249

Russell S, Blackstock T, Christie M, Clarke M, Davies K, Duigan C, Durance I, Elliot R, Evans H, Falzon C, Frost P, Ginley S, Hockley N, Hourahane S, Jones B, Jones L, Korn J, Ogden P, Pagella S, Pagella T, Pawson B, Reynolds B, Robinson D, Sanderson B, Sherry J, Skates J, Small E, Spence B, Thomas T (2011) Status and changes in the UK’s ecosystems and their services to society: Wales. In: UK National Ecosystem Assessment (ed) UK National Ecosystem Assessment Technical Report. UNEP-WCMC, Cambridge, pp 979–1044

Schellhorn NA, Macfadyen S, Bianchi FJJA, Williams DG, Zalucki MP (2008) Managing ecosystem services in broadacre landscapes: what are the appropriate spatial scales? Aust J Exp Agric 48(12):1549–1559

Seppelt R, Dormann CF, Eppink FV, Lautenbach S, Schmidt S (2011) A quantitative review of ecosystem service studies: approaches, shortcomings and the road ahead. J Appl Ecol 48(3):630–636

Seppelta R, Fath B, Burkhard B, Fisher JL, Grêt-Regamey A, Lautenbach S, Perth P, Hotesi S, Spangenberg J, Verburg PH, Van Oudenhoven APE (2012) Form follows function? Proposing a blueprint for ecosystem service assessments based on reviews and case studies. Ecol Indic 21:145–154

Sherrouse BC, Clement JM, Semmens DJ (2011) A GIS application for assessing, mapping, and quantifying the social values of ecosystem services. Appl Geogr 31(2):748–760

Simonit S, Perrings C (2011) Sustainability and the value of the ‘regulating’ services: wetlands and water quality in Lake Victoria. Ecol Econ 70(6):1189–1199

Swallow B, Kallesoe M, Iftikhar U, van Noordwijk M, Bracer C, Scherr S, Raju KV, Poats S, Duraiappah A, Ochieng B, Mallee H, Rumley R (2007) Compensation and rewards for environmental services in the developing world: framing pan-tropical analysis and comparison. ICRAF Working Paper no. 32. ICRAF, Nairobi

Sinclair FL, Pagella TF Negotiation of synergies and tradeoffs amongst impacts of landuse change on ecosystem service provision. Ecol Soc (in review)

Sinclair FL, Walker DH (1998) Acquiring qualitative knowledge about complex agroecosystems. Part 1: representation as natural language. Agric Syst 56(3):341–363

Swetnam RD, Fisher B, Mbilinyi BP, Munishi PKT, Willcock S, Ricketts T, Mwakalila S, Balmford A, Burgess ND, Marshall AR, Lewis SL (2011) Mapping socio-economic scenarios of land cover change: a GIS method to enable ecosystem service modelling. J Environ Manage 92(3):563–574

Tallis H, Polasky S (2009) Mapping and valuing ecosystem services as an approach for conservation and natural-resource management. Year Ecol Conserv Biol 2009(1162):265–283

Tilman D, Fargione J, Wolff B, D’Antonio C, Dobson A, Howarth R, Schindler D, Schlesinger WH, Simberloff D, Swackhamer D (2001) Forecasting agriculturally driven global environmental change. Science 292(5515):281–284

Troy A, Bagstad K (2009) Estimating ecosystem services in Southern Ontario [internet]. Toronto (ON); [cited 2011 April 20]; [73 pages]. Available from: http://www.mnr.gov.on.ca/stdprodconsume/groups/lr/@mnr/@lueps/documents/document/279512.pdf

Troy A, Wilson MA (2006) Mapping ecosystem services: practical challenges and opportunities in linking GIS and value transfer. Ecol Econ 60(2):435–449

van Lieshout M, Dewulf A, Aarts N, Termeer C (2011) Do scale frames matter? Scale frame mismatches in the decision making process of a “Mega Farm” in a small Dutch village. Ecol Soc 16(1):38

Vanclay JK, Prabhu R, Sinclair FL (2006) Realizing community futures: a practical guide to harnessing natural resources. Earthscan, London

van Wijnen HJ, Rutgers M, Schouten AJ, Mulder C, de Zwart D, Breure AM (2011) How to calculate the spatial distribution of ecosystem services—Natural attenuation as example from The Netherlands. Sci Total Environ 415:49–55

Wang E, Cresswell H, Bryan B, Glover M, King D (2009) Modelling farming systems performance at catchment and regional scales to support natural resource management. Njas-Wagening J Life Sci 57(1):101–108

Wendland KJ, Honzák M, Portela R, Vitale B, Rubinoff S, Randrianarisoa J (2010) Targeting and implementing payments for ecosystem services: opportunities for bundling biodiversity conservation with carbon and water services in Madagascar. Ecol Econ 69(11):2093–2107

Willemen L, Hein L, van Mensvoort MEF, Verburg PH (2010) Space for people, plants, and livestock? Quantifying interactions among multiple landscape functions in a Dutch rural region. Ecol Ind 10(1):62–73

Wynne-Jones S (2013) Connecting payments for ecosystem services and agri-environment regulation: an analysis of the Welsh Glastir Scheme. J Rural Stud 31:77–86

Zhang W, Ricketts TH, Kremen C, Carney K, Swinton SM (2007) Ecosystem services and dis-services to agriculture. Ecol Econ 64(2):253–260

Zhang M, Wang K, Liu H, Zhang C (2011) Responses of spatial-temporal variation of Karst ecosystem service values to landscape pattern in northwest of Guangxi, China. Chin Geogr Sci 21(4):446–453

Acknowledgments

This research was funded under an Engineering and Physical Sciences Research Council (EPSRC) studentship grant and the Flood Risk Management Research Consortium (FRMRC). The World Agroforestry Centre (ICRAF) contributed to this research as part of its involvement in CGIAR Research Programs: Forests, Trees and Agroforestry; Humid Tropics and Dryland Systems. All data presented and conclusions reached in this article are the sole responsibility of the authors and do not imply any agreement or approval of institutions acknowledged here.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License which permits any use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and the source are credited.

About this article

Cite this article

Pagella, T.F., Sinclair, F.L. Development and use of a typology of mapping tools to assess their fitness for supporting management of ecosystem service provision. Landscape Ecol 29, 383–399 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10980-013-9983-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10980-013-9983-9