Abstract

International research collaboration is on the rise—and at the same time, women face potential barriers. Based on responses to surveys conducted among groups of women engineers, this article addresses (1) women’s frequency of international research collaboration; (2) the barriers to collaboration reported for both self and for other women; and (3) the patterns among women students as well as professionals, by national regions. Findings of this study have implications for policies to broaden participation in the increasingly important arena of international research collaboration, based on women in engineering, the scientific field in which women are most underrepresented. This makes the case focal for the study of women, science, and policy.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

Of the 915 persons who applied, duplicate replies and surveys were removed (to the extent identified/known) and (4) replies and surveys of men were removed for this present analysis focusing on women.

The form of this question varied somewhat between the three waves of application, but for each wave, the responses to the questions were checked and coded so that students were coded as “students” and those who were “not students” as professionals (types of ranks/positions).

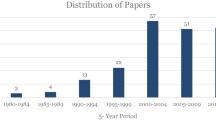

In Fig. 1, the residual bar is for self-reported responses that are not classifiable into the numeric categories of prior international research collaboration, represented by “at least one” (3.1 %) or “other” (0.9 %) with responses, for examples, of “discussed a project, some follow-up,” “will teach an international course,” and “did undergraduate education and thesis in Europe.”

As the Method points out, marriage and children do not appear to be impediments to applying for the summit. Thus, the lower reported importance of family conditions as a barrier to international research collaboration is not an artifact of the group applying.

References

Abramo, G., D’Angelo, C. A., Di Costa, F., & Solazzi, M. (2011). The role of information asymmetry in the market for university-industry research collaboration. Journal of Technology Transfer, 36, 84–100.

Abramo, G., D’Angelo, C. A., & Murgia, G. (2013). Gender differences in research collaboration. Journal of Informetrics, 7, 811–822.

Ackers, L. (2008). Internationalization, mobility and metrics: A new form of indirect discrimination? Minerva, 46, 411–435.

Bagshaw, D., Lepp, M., & Zorn, C. (2007). International research collaboration: Teams and managing conflict. Conflict Resolution Quarterly, 24, 433–446.

Bastedo, M., & Gumport, P. (2003). Access to what? Mission differentiation and academic stratification in US public higher education. Higher Education, 46, 341–359.

Beaver, D. D. B. (2001). Reflections on scientific collaboration (and its study): Past, present, and future. Scientometrics, 52, 365–377.

Bozeman, B., & Corley, E. (2004). Scientists’ collaboration strategies: Implications for scientific and technical human capital. Research Policy, 33, 599–616.

Bozeman, B., & Gaughan, M. (2011). How do men and women differ in research collaborations? An analysis of the collaborative motives and strategies of academic researchers. Research Policy, 40, 1393–1402.

Bozeman, B., Kay, D., & Slade, C. (2013). Research collaboration in universities and academic entrepreneurship: The state-of-the-art. Journal of Technology Transfer, 38, 1–67.

Brown, J. (1986). Evaluations of self and others: Self-enhancement biases in social judgments. Social Cognitions, 4, 353–376.

Caprile, M., Addis, E., Castaño, C., Klinge, I., Larios, M., Meulders, D., et al. (2012). Meta-analysis of gender and science research: Synthesis report. Luxembourg: Publications Office of the European Union.

Charles, M., & Bradley, K. (2009). Indulging our gendered selves? Sex segregation by field of study in 44 countries. American Journal of Sociology, 114, 924–976.

Childress, L. (2010). The twenty-first century university: Developing faculty engagement in internationalization. New York: Peter Lang.

Clark, B. (1997). Small worlds, different worlds: The uniqueness and troubles of the american academic profession. Daedalus, 126, 21–42.

Corley, E. (2005). How do career strategies, gender, and work environment affect faculty productivity in university-based science centers? Review of Policy Research, 22, 637–655.

Ellemers, N., van den Heuvel, H., Gilder, D., Maass, A., & Bonvini, A. (2004). The underrepresentation of women in science: Differential commitment or the queen bee syndrome? British Journal of Social Psychology, 43, 315–338.

Engels, A., & Ruschenburg, T. (2008). The uneven spread of global science: Patterns of international research collaboration in global environmental change research. Science and Public Policy, 35, 347–360.

European Commission. (2007). The European research area: New perspectives. Green Paper, Brussels. http://ec.europa.eu/research/era/pdf/era-greenpaper_en.pdf

European Commission. (2009). Drivers of international collaboration in research. Luxembourg: Directorate-General for research, Publications Office of the European Union.

Finkelstein, M., Walker, E., & Chen, R. (2009) The internationalization of American Faculty. Presented at conference on the changing academic profession over 1992–2007: International, comparative, and quantitative perspectives, Hiroshima, Japan.

Fox, M. F. (2005). Gender, family characteristics, and publication productivity among scientists. Social Studies of Science, 35, 131–150.

Fox, M. F. (2008). Institutional transformation and the advancement of women faculty: The case of academic science and engineering. In J. C. Smart (Ed.), Higher education: Handbook of theory and research (Vol. 23). Berlin: Springer.

Fox, M. F., & Faver, C. (1984). Independence and cooperation in research: The advantages and costs of collaboration. Journal of Higher Education, 55, 347–359.

Fox, M. F., & Mohapatra, S. (2007). Social-organizational characteristics of work and publication productivity among academic scientists in doctoral-granting departments. The Journal of Higher Education, 78, 542–571.

Frame, J. D., & Carpenter, M. P. (1979). International research collaboration. Social Studies of Science, 9, 481–497.

Frehill, L. M., & Zippel, K. (2010). Survey of doctoral recipients, 2006: Findings on gender and international collaborations of academic scientists and engineers. Report to the National Science Foundation, October 2010.

Garrison, E. (1991). A history of engineering and technology. Boca Raton, FL: CRC.

Gaughan, M. (2006). Institutional assessment of women in science: Introduction to the symposium. Journal of Technology Transfer, 31, 307–310.

Gazni, A., Sugimoto, C. R., & Didegah, F. (2012). Mapping world scientific collaboration: Authors, institutions, and countries. Journal of the American Society for Information Science and Technology, 63, 323–335.

Glanzel, W. (2001). National characteristics in international scientific co-authorship relations. Scientometrics, 51, 69–115.

Glanzel, W., & de Lange, C. (2002). A distributional approach to multinational measures of international research collaboration. Scientometrics, 54, 75–89.

Grayson, L. (1993). The making of an engineer. New York: Wiley.

Henkel, R. (1976). Tests of significance. Newbury Park, CA: Sage.

Hennemann, S., Rybski, D., & Liefner, I. (2012). The myth of global science collaboration—Collaboration patterns in epistemic communities. Journal of Informetrics, 6, 217–225.

Jappe, A. (2007). Explaining international collaboration in global environmental change research. Scientometrics, 71, 367–390.

Jeong, S., Choi, J. Y., & Kim, J.-Y. (2014). On the drivers of international research collaboration: The impact of informal communication, motivation, and research resources. Science and Public Policy, 4, 520–531.

Katz, J. S., & Martin, B. R. (1997). What is research collaboration? Research Policy, 26, 1–18.

Larivière, V., Ni, C., Gingras, Y., Cronin, B., & Sugimoto, C. R. (2013). Bibliometrics: Global gender disparities in science. Nature, 504, 211–213.

Lee, S., & Bozeman, B. (2005). The impact of research collaboration on scientific productivity. Social Studies of Science, 35, 673–702.

Luukkonen, T., Persson, O., & Siverstsen, G. (1992). Understanding patterns of international scientific collaboration. Science, Technology and Human Values, 17, 101–126.

MacKenzie, D., & Wajcman, J. (1999). The social shaping of technology (2nd ed.). Buckingham: Open University Press.

Mattis, M. C. (2007). Upstream and downstream in the engineering pipeline. In R. J. Burke & M. C. Mattis (Eds.), Women and minorities in science, technology, engineering and mathematics. Cheltenham/Northampton, MA: Edward Elgar.

National Science Board. (2012). Science and engineering indicators. Arlington, VA: National Science Foundation.

Peters, M. (2006). The rise of global science and the emerging political economy of international research collaboration. European Journal of Education, 41, 225–244.

Peterson, M. (2009). Cross-cultural comparative studies and issues in international research collaboration. In D. Buchanan & A. Bryman (Eds.), Sage handbook of organizational research methods. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Prpić, K. (2002). Gender and productivity differentials in science. Scientometrics, 55, 27–58.

Rossiter, M. (2012). Women scientists in America: Forging a new world since 1972. Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press.

Silim, A., & Crosse, C. (2014). Women in engineering: Fixing the talent pipeline. London: Institute for Public Policy Research.

Smykia, E., & Zippel, K. (2010). Literature review: Gender and international research collaboration. Report to the National Science Foundation.

Tokunaga, H. T. (2015). Fundamental statistics for the social and behavioral sciences. Newbury Park, CA: Sage.

Twenge, J. M., & Campbell, W. K. (2002). Self-esteem and socioeconomic status: A meta-analytic review. Personality and Social Psychology Review, 6, 59–71.

UNESCO Institute for Statistics. (2011). Women in science. UIS Fact Sheet, No. 14.

Wagner, C. S. (2006). International collaboration in science and technology: Promises and pitfalls. In L. Box & R. Engelhard (Eds.), Science and technology for development. London: Anthem Press.

Wagner, C. S., & Leydesdorff, L. (2005). Network structure, self-organization, and the growth of international research collaboration. Research Policy, 34, 1608–1618.

Ynalvez, M. A., & Shrum, W. (2011). Professional networks, scientific collaboration, and publication productivity in resource-constrained research institutions in a developing country. Research Policy, 40, 204–216.

Acknowledgements

The research reported here was supported, in part, by the National Science Foundation (award #1047714). For comments on an earlier draft of this article, we thank Carolina Canibano.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Fox, M.F., Realff, M.L., Rueda, D.R. et al. International research collaboration among women engineers: frequency and perceived barriers, by regions. J Technol Transf 42, 1292–1306 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10961-016-9512-5

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10961-016-9512-5