Abstract

Qualitative evidence points to the engagement of religious coping strategies when facing adversity, and evidence also highlights the effectiveness of cognitive reappraisal in reducing the impact of distressing emotions on well-being. It has been suggested that religious practices could facilitate the use of reappraisal, by promoting reframing of negative cognitions to alter emotional states. However, the link between religiosity and reappraisal in influencing resilience against symptoms of distress is not known. The current study (N = 203) examined connections among these aspects, using self-reported measures of religious coping, habitual use of specific coping strategies (positive reappraisal) and perceived confidence in using coping strategies, as well as questionnaires assessing symptoms of distress (anxiety and depression). Results point to a mediating role of reappraisal and coping self-efficacy as part of mechanisms that provide a protecting role of religious coping against emotional distress. These results provide novel scientific evidence further validating millennia-old traditional coping practices and shed light on psychological factors influencing adaptive behaviors that promote increased resilience, reduce symptoms of distress, and maintain emotional well-being. These findings inform general counseling practices and counseling of religious clients alike.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Facing adversity is a main factor influencing many people’s “return to religion.” Indeed, religious coping has been reported as one of the most common forms of coping in times of crisis, regardless of religious or cultural affiliation (Peres et al. 2007). Irrespective of the stressor type (e.g., death of loved ones, personal challenges, etc.), oftentimes individuals use their religiosity to cope. Putting their fate “in God’s hands” and accepting their experiences as “God’s will” gives them a sense of safety, support, and tenacity to persevere through stressful situations (Simonič and Klobučar 2017; Talik and Skowroński 2018). The prevalence of religious coping is not surprising, given the omnipresence of religious and spiritual beliefs and practices throughout the history of human civilizations and cultures, from animism to poly- and monotheism. It is estimated that over 80% of the World’s current population is associated with organized religions (Vasile 2013), thus making Homo Religiosus (Eliade 1981, 1985, 1988) a likely reality. But what is it in the coping effectiveness of these millennia-old traditional practices that could be quantified using contemporary psychological tools? The present study addresses this question by investigating the relation between self-reported measures of religious coping and measures of coping strategies that provide protection against symptoms of distress. Clarification of these issues is important because it informs both general counseling practices and counseling of religious clients.

The main focus here is on religious coping resources, although the constructs of religiosity and spirituality have overlapping features and influence one another (King and Crowther 2004). Religiosity is of particular interest due to its multifaceted nature and involvement in applying meaning to one’s life, providing resources to solve problems, and supporting one’s ability to cope during stressful life events. Aside from overlapping features with spirituality, including the drive to find sacred meaning and form a relationship with a higher being, religiosity is also relatively more community-oriented and associated with organized practices and resources influencing belief and understanding (Austin et al. 2018; King and Crowther 2004). However, the multidimensional and often abstract nature of religious beliefs and attitudes (Maltby and Day 2003; Pargament 2001) also makes it difficult to establish direct relations between measures of religiosity and psychological constructs or outcomes of well-being (e.g., anxiety and depression symptoms). Hence, the link between religiosity and psychological constructs is more often modeled through specific religious coping strategies and behaviors (Maltby and Day 2003; Pargament 2001).

Concepts from emotion science point to possible links with specific religious coping strategies, such as the link between cognitive reappraisal, as an emotion regulation strategy (Gross 1998; Thomas and Savoy 2014), and positive religious coping strategies (Cornish et al. 2017; Peres et al. 2007; Wallace and Shapiro 2006). Cognitive reappraisal involves reframing or reassessing negative cognitions to alter emotional states, which typically results in more positive control of negative situations (Gross 1998). Positive reappraisal is considered a particularly adaptive emotion regulation strategy, as it maintains emotional stability during challenging or stressful life circumstances and provides protection against symptoms of distress typically associated with affective disorders (anxiety, depression, post-traumatic stress disorder) (Llewellyn et al. 2013; Resick et al. 2013). Similarly, positive religious coping strategies have also been associated with positive mental health outcomes (Cornish et al. 2017; Peres et al. 2007; Wallace and Shapiro 2006), such as increased emotional well-being and posttraumatic growth (Park et al. 2017; Talik and Skowroński 2018; Trevino et al. 2012).

In fact, some forms of religious coping have been referred to as emotion regulation strategies in action (Thomas and Savoy 2014), and cognitive reappraisal is one such specific strategy. Indeed, religious individuals spontaneously engage in positive reappraisals, across a variety of religions (Garssen et al. 2015; Vishkin et al. 2016). For instance, benevolent religious reappraisal is one of the most commonly used religious coping strategies (Talik and Skowroński 2018) and involves redefining a stressful circumstance as a prospect for spiritual growth or as another possible beneficial outcome, such as a valuable learning opportunity (Pargament et al. 2000; Talik and Skowroński 2018). Relevant statements reflecting benevolent religious reappraisal include: “I tried to see how God might be trying to strengthen me in this situation” (Pargament et al. 2000). Cognitive reappraisal of a similar situation could also emphasize aspects related to personal growth, but without referring to a divine intervention: “Losing my job challenged me to gain the skills needed for finding my dream job.” Similarly, losing loved ones could be reappraised with or without the inclusion of a divine being (e.g., “My parents are with God now” or “At least now they are no longer suffering”). Given the similarity between positive religious reappraisal and positive cognitive reappraisal, it is possible that the latter is part of the mechanisms contributing to the effectiveness of religious coping strategies in protecting against symptoms of distress when facing adversity. However, this hypothesis has not been tested before, and hence one of the main goals of the present study is to investigate the role of cognitive reappraisal as a possible mediator in the link between religious coping and well-being.

Aside from specific emotion regulation strategies, such as reappraisal, individuals’ perceived confidence in their ability to cope with stressful or threatening situations is also important to consider in trying to elucidate the mechanisms by which religious coping provides protection against distress. This perceived confidence, called coping self-efficacy (CSE), is related to general self-efficacy (Bandura 2010) and has been linked to various positive health outcomes in both clinical and non-clinical groups (Benight and Harper 2002; Chesney et al. 2006; Cieslak et al. 2008). Given its role in predicting and managing coping behaviors at a more general level (Benight and Harper 2002; Chesney et al. 2006), and the role of religious coping strategies in conferring confidence in one’s coping abilities, we also tested the role of CSE as a possible mediator in the link between religious coping and well-being.

To summarize, the present study investigated the mechanisms by which religiosity benefits mental health (Miller and Kelley 2005). This was done by testing mediation models involving links between self-reported measures of religious coping and measures of specific coping strategies (reappraisal), along with the perceived confidence in performing coping behaviors (CSE), in providing protection against symptoms of distress (anxiety and depression). We propose that religious coping is linked to both the habitual use of cognitive reappraisal as an emotion regulation strategy and high levels of CSE. In turn, habitual engagement of reappraisal and high levels of perceived coping abilities, as fostered by religious coping, results in more adaptive behaviors that promote increased resilience, reduce symptoms of distress, and maintain emotional well-being.

Methods

Participants

Analyses were performed on data from 203 young adult participants (155 females) with an age range of 18–39 years old (M = 21.98, SD = 4.75), recruited from the University of Illinois subject pool and the larger Urbana-Champaign community, via flyers and online advertisements. Our sample size was larger than, or comparable to, those reported in other published work using similar approaches (Cieslak et al. 2008; Llewellyn et al. 2013; Luberto et al. 2014). Experimental protocols were approved by the University’s Institutional Review Board, and all participants provided written informed consent prior to data collection. All participants were compensated for their time with either course credit or money ($10/h).

Self-Report Measures

Religious Coping was assessed using the Religion subscale of Brief COPE (Carver 1997), which is the brief form of the COPE inventory (Carver et al. 1989). Brief COPE consists of 28 items that assess how people respond when confronted with difficult or stressful events in their lives, using a 4-point scale (1 = “I usually don't do this at all”; 4 = “I usually do this a lot”). The following 14 subscales are part of the Brief COPE: self-distraction, active coping, substance use, denial, use of emotional support, use of instrumental support, behavioral disengagement, venting, positive reframing, planning, humor, acceptance, self-blame, and religion. The Religion subscale consists of 2 items and includes questions relevant to using religion as a coping strategy (e.g., “I've been trying to find comfort in my religion or spiritual beliefs”). The ratings on the two items are summed to obtain the rating for the Brief COPE-R subscale, reflecting the degree to which individuals resort to religious coping. Higher scores indicate that, when dealing with stress, one has a higher frequency of resorting to religious coping strategies.

For a subset of the participants (N = 57), the level of religiosity/spirituality was also assessed using the following general question, with the note that the rating may be independent of beliefs related to a specific religion or the frequency of participating in formal religious activities, using a 10-point scale (1 = “Not at all religious/spiritual”; 10 = “Very religious/spiritual”): “Please rate, on a scale from 1 to 10, how religious/spiritual you consider yourself.” Because this question was optional (given its possibly sensitive nature), not all participants answered it. We found that one’s level of religiousness, as assessed by this single-item scale, was positively correlated with the Brief COPE-R scale (r = 0.827, p < 0.001, n = 57), thus showing a strong link between how religious/spiritual one considers themselves and the habitual use of religious coping strategies, as measured with a standardized tool. Notably, the strong positive correlation between these measures is consistent with the idea that the construct of religiosity can be modeled through religious coping processes and behaviors (Maltby and Day 2003; Pargament 2001). This evidence justified further analyses involving the Brief COPE-R subscale to investigate relations with other variables of interest for the present investigation (see below). Finally, aside from these measures, as part of the experimental procedure, participants also had the opportunity to provide details regarding their specific religious affiliation.

Cognitive Reappraisal was assessed using the Reappraisal subscale of the Emotion Regulation Questionnaire (ERQ), which assesses individual differences in the habitual use of two emotion regulations strategies: cognitive reappraisal and expressive suppression (Gross and John 2003). Participants are presented with 10 statements regarding the way they control their emotionsal reponses (e.g., “When I want to feel less negative emotion, I change the way I’m thinking about the situation”) and are asked to assign a value that they feel reflects the degree to which the statement applies to them, using a 7-point scale (1 = “Strongly disagree; 7 = “Strongly agree”). Two distinct aspects of emotion processing are targeted: emotional experience (i.e., what the subjects feel like inside) and emotional expression (i.e., how the subjects show their emotions). Item ratings are separated and summed to create overall reappraisal (ERQ-R; 6-items) and suppression (ERQ-S; 4-items) scores. Higher scores on the subscales signify one’s tendency to regulate their emotions using cognitive reappraisal and expressive suppression, respectively. These two subscales were separately used in the following analyses.

Coping Self-Efficacy was assessed using the Coping Self-Efficacy (CSE) questionnaire (Chesney et al. 2006), which consists of 26 items measuring one’s confidence in performing coping behaviors when faced with challenges. Participants are asked “When things aren’t going well for you, or when you’re having problems, how confident or certain are you that you can do the following…” Then, they rate the extent to which they believe they could perform behaviors important to adaptive coping (e.g., “Sort out what can be changed and what cannot be changed”; “look for something good in a negative situation”), using an 11-point scale (0 = “Cannot do at all”; 5 = “Moderately certain can do”; 10 = “Certain can do”). An overall CSE score is created by summing the item ratings, and higher scores indicate more confidence in utilizing adaptive coping abilities.

Anxiety Symptoms were assessed using the State-Trait Anxiety Inventory (STAI), which measures anxiety in adults (Spielberger et al. 1970). The STAI consists of two forms containing 20 items each. STAI-Y1 measures momentary (“state”) anxiety by evaluating how the subjects feel “right now, at this moment”, and STAI-Y2 measures longer-lasting (“trait”) anxiety by evaluating how the participant feel “in general”. The scale uses “I feel/I am” statements that are rated on 4-points scales, as follows: 1 = “Not at all”(STAI-Y1)/“Almost never” (for STAI-Y2); 4 = “Very much so” (STAI-Y1)/“Almost always” (STAI-Y2). The present study used the STAI Y-2 scores, with higher scores demonstrating more severe anxiety symptoms, in general.

Depressive Symptoms were measured using the Beck Depression Inventory (BDI) (Beck et al. 1961; Sanz and Paz Garcia-Vera 2007). The BDI consists of 21 items, which participants are instructed to answer based on how they are feeling at the moment or have felt during longer periods, using a 4-point scale (0 = “I do not feel sad”; 3 = “I am so sad or unhappy that I can’t stand it”). The values assigned to each answer are summed for the total BDI score, which determines the depression severity – higher scores indicate more severe depressive symptoms (Whisman et al. 2000). The BDI scores were assessed to complement the anxiety measures, as outcomes of emotional distress/dysregulation, and to test for possible specificity of effects, as previously employed (Dolcos et al. 2015; Hu and Dolcos 2017; Moore et al. 2018).

Analyses

First, Pearson’s correlations were used to assess bivariate relations involving the targeted measures, as follows: religious coping (Brief COPE-R), cognitive reappraisal (ERQ-R), coping efficacy (CSE), and psychological outcomes of emotional distress – anxiety (STAI-Y2) and depression (BDI). These correlations also confirmed the appropriateness of testing mediation models (Hayes 2012) and helped clarify the specificity of expected relations (e.g., test that expected effects are specific to reappraisal and are different from those associated with a different emotion control strategy: suppression). Then, targeted mediation models tests were conducted with reappraisal and CSE as the mediators, religious coping as the predictor variable, and anxiety or depressive scores as outcome variables, and were performed using bootstrapping procedures with 5,000 samples with replacement. To test the specificity of the models, alternative mediation models with other configurations of the variables of interest were also performed. Also, to further explore the relations between the mediators, we performed post-hoc analyses that included both reappraisal and CSE as mediators, with religious coping as the predictor variable and anxiety or depression scores as the outcome variables. All statistical analyses were conducted using SPSS for Windows (IBM, Version 25).

Results

Religious Coping is Linked to Cognitive Reappraisal, Coping Self-Efficacy, and Distress Outcomes

As expected, religious coping (Brief COPE-R) was positively correlated with reappraisal (ERQ-R) (r = 0.251, p < 0.001; Table 1), indicating that those who use religious coping also habitually use reappraisal as an emotion regulation strategy. Importantly, as also shown in Table 1, religious coping was negatively correlated with suppression (ERQ-S; r = − 0.140, p = 0.047). In addition, as predicted, religious coping was positively correlated with coping self-efficacy (CSE) (r = 0.329, p < 0.001), indicating that those who use religious methods of coping have increased confidence in their general abilities to cope. Regarding the outcomes of emotional distress, religious coping was negatively correlated with both trait anxiety (STAI-Y2; r = − 0.199, p = 0.004) and depression scores (BDI; r = − 0.176, p = 0.012), showing that individuals who resort to religion for coping also exhibit less anxiety and depressive symptoms.

Reappraisal and Coping Self-Efficacy Mediate the Protecting Role of Religious Coping Against Emotional Distress

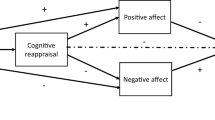

Mediation analyses examining whether the associations between religious coping (Brief COPE-R) and emotional distress symptoms (STAI-Y2 and BDI) were mediated by cognitive reappraisal (ERQ-R) and coping efficacy (CSE) also confirmed our hypothesis (Fig. 1). Namely, our results showed that the habitual use of reappraisal as an emotion regulation strategy and higher levels of CSE mediated the link between religious coping and decreased anxiety (Fig. 1a) and depression (Fig. 1b) symptoms.

Cognitive reappraisal and CSE mediate the link between religious coping and reduced emotional distress. Displayed are the mediation models demonstrating significant negative indirect effects of reappraisal and CSE on the relation between religious coping and decreased anxiety (a) and depression (b) symptoms. Path a refers to the relation from the predictor variable (X) to the corresponding mediator variables (M), and path b refers to the relation from M to the outcome variable (Y), while controlling for X. Path c refers to the total effect from X to Y, and path c’ refers to the direct effect from X to Y controlling for M. The indirect effects are represented by the interaction term ab, and the significance of these effects was tested using bootstrapped 95% confidence intervals (CIs). Unstandardized regression coefficients are displayed; *significant at p < 0.05, **significant at p < 0.01

To further confirm the specificity of reappraisal and CSE as mediators of these relations, additional mediation analyses were performed with alternative configurations, which further clarified the directionality of the relations among these variables. First, reappraisal was included as the predictor variable, religious coping as the mediator variable, and anxiety as the outcome variable. This model was nonsignificant (ab = − 0.0604, bootstrapped 95% CI = [− 0.1377, 0.0025]), indicating that the specificity of our proposed mechanism, with reappraisal more strongly mediating the link between religious coping and reduced symptoms of anxiety, holds. Similarly, a model with coping self-efficacy configured as the predictor variable, religious coping as the mediator variable, and trait anxiety as the outcome variable was also nonsignificant (ab = 0.0001, bootstrapped 95% CI = [− 0.0133, 0.0130]), again supporting the specificity of the proposed mechanism for anxiety.

In the case of depression, the alternative model with reappraisal and religious coping swapped (with coping self-efficacy as the predictor variable, religious coping as the mediator variable, and depressive symptoms as the outcome) was significant (ab = − 0.0335, bootstrapped 95% CI = [− 0.0764, − 0.0023]), suggesting less specificity of reappraisal as a mediator. However, the same model with the CSE and religious coping swapped was nonsignificant (ab = 0.0002, bootstrapped 95% CI = [− 0.0060, 0.0074]), indicating support for the specificity of our suggested mediating role of CSE in the association between religious coping and decreased symptoms of depression. Overall, these analyses further confirm the mediating role of cognitive reappraisal and CSE in the link between religious coping and reduced symptoms of distress. Although these relations showed slightly increased specificity for anxiety symptoms, the present results provide evidence that habitual engagement of reappraisal and increased CSE, as fostered by religious coping, result in reduced symptoms of anxiety and depression, thus promoting resilience against emotional distress and increased well-being.

To further understand the mechanistic effects of reappraisal and CSE, we ran additional post-hoc tests of these variables using parallel multiple mediation models. These tests allowed us to determine the strengths of the factor effects using completely standardized indirect effects (abcs) of the link between religious coping and outcomes of distress. In a first model, religious coping was included as the predictor variable, reappraisal and CSE as mediator variables, and anxiety symptoms as the outcome variable. This model was significant (ab = − 0.9727, bootstrapped 95% CI = [− 1.4290, − 0.5852]), but the indirect effect of reappraisal alone was nonsignificant and weaker than the indirect effect of CSE (Reappraisal, ab = − 0.0545, bootstrapped 95% CI = [− 0.2396, 0.1127], abcs = − 0.0116, bootstrapped 95% CI = [− 0.0515, 0.0263]; CSE, ab = − 0.9181, bootstrapped 95% CI = [− 1.3677, − 0.5383], abcs = − 0.1950, bootstrapped 95% CI = [− 0.2807, − 0.1165]). A second parallel multiple mediator model, with the same predictor and mediator variables, but with depressive symptoms as the outcome variable, was also significant (ab = − 0.5007, bootstrapped 95% CI = [− 0.7813, − 0.2724]). Similar to the first parallel multiple mediation model, the indirect effect of reappraisal was nonsignificant and weaker than that of CSE (Reappraisal, ab = − 0.0031, bootstrapped 95% CI = [− 0.0968, 0.0992], abcs = − 0.0011, bootstrapped 95% CI = [− 0.0339, 0.0351]; CSE, ab = − 0.4976, bootstrapped 95% CI = [− 0.8008, − 0.2755], abcs = − 0.1791, bootstrapped 95% CI = [− 0.2640, − 0.1023]). Overall, these exploratory analyses aimed to assess the potential additive effects of the mediators suggest a stronger role of CSE in reducing symptoms of distress, as influenced by religious coping.

Discussion

The present study showed that (1) religious coping was positively associated with cognitive reappraisal and coping efficacy, and negatively associated with symptoms of anxiety and depression. Moreover, (2) reappraisal and coping efficacy mediated the protecting role of religious coping strategies against symptoms of anxiety and depression.

The positive association between religious coping and cognitive reappraisal is consistent with previous evidence linking religiosity and cognitive reappraisal (Vishkin et al. 2016) and provide further support to the idea that religious coping strategies act as emotion regulation strategies in action (Thomas and Savoy 2014). The positive association between religious coping and CSE is also important because it extends this link to the more general perceived ability to cope, beyond the habitual engagement of a specific emotion regulation strategy. These data provide support to ideas suggesting conceptual overlaps between cognitions and behaviors associated with reappraisal and CSE and aspects attributed to religious coping, including meaning making, feelings of control, and resilience (Israel-Cohen et al. 2016; Maltby and Day 2003; Pargament 2001; Park 2013).

The negative association between religious coping and symptoms of distress provides further support to previous evidence pointing to beneficial effects of using religious coping strategies on mental health (Cornish et al. 2017; Peres et al. 2007; Wallace and Shapiro 2006). For instance, religious coping strategies have been associated with increased posttraumatic growth, well-being, and positive emotional states (Park et al. 2017; Talik and Skowroński 2018; Trevino et al. 2012). The present study extends these findings by showing that the use of religious coping is also associated with reduced anxiety and depression scores. Moreover, as discussed below, the present investigation also provided evidence regarding possible mechanisms by which religious coping protects against such symptoms of distress.

The significant mediating roles of cognitive reappraisal and coping efficacy in the protective effect of religious coping against symptoms of anxiety and depression provide novel evidence regarding the associated mechanisms. These findings extend evidence concerning separate links between these two measures and religious coping (Cornish et al. 2017; Peres et al. 2007; Talik and Skowroński 2018; Thomas and Savoy 2014; Trevino et al. 2012; Wallace and Shapiro 2006), on the one side, and their relations with emotional dysregulation (Cieslak et al. 2008; Llewellyn et al. 2013; Moore et al. 2018), on the other side. Moreover, the present evidence points to a central position of cognitive reappraisal and CSE as mediators of the link between religious coping and symptoms of distress. Follow-up parallel multiple mediation tests of reappraisal and CSE identified a stronger indirect effect of CSE on the relation between religious coping and both anxiety and depressive symptoms. While these results were exploratory in nature, they suggest that perceived confidence in one’s abilities to cope and therefore utilizing religious coping, may be more protective against anxiety and depressive symptoms than reappraisal. At any rate, as showed by the separate mediation models, both reappraisal and self-efficacy provide protection against emotional distress, together with religious coping.

Given the benefits of habitually engaging cognitive reappraisal as an emotion regulation strategy and the common presence of positive reappraisals across a variety of religious affiliations (Garssen et al. 2015; Vishkin et al. 2016), it may as well be the case that religious reappraisal is the ultimate form of reappraisal in those who believe. The centrality of reappraisal goes hand in hand with that of the CSE, which has also been associated with mental health benefits and enhanced well-being, as shown by evidence of its role in decreasing anxiety and reducing avoidant behaviors (Bandura 2010; Benight and Harper 2002; Chesney et al. 2006). This is also consistent with the suggestion that religious coping strategies are cognitive emotion regulation strategies at work (Thomas and Savoy 2014), aiming to facilitate finding meaning, gaining control, and improving resilience. Hence, it is not surprising that, in turn, this also affects one’s perceived capabilities to effectively cope with life challenges, as reflected in the enhanced CSE scores (Israel-Cohen et al. 2016). Our findings provide strong empirical support to these theoretical suggestions and identify cognitive reappraisal and CSE as part of the mechanisms of self-regulation by which religious coping decreases symptoms of emotional dysregulation.

The centrality of cognitive reappraisal and CSE as mediators of the link between religious coping and distress symptoms is also supported by additional analyses testing for the specificity of the identified effects. Importantly, the mediation models were significant when religious coping was the primary predictor, rather than the mediator or outcome of reappraisal or CSE. Moreover, further analyses provided support for specificity of the effects to cognitive reappraisal and CSE, rather than to other emotion regulation strategies (suppression). However, the effects were similar for anxiety and depression in our mediation models, although slight differences in the alternative models tested here were identified. Specifically, findings from our alternative mediation models (with reappraisal as predictor) point to possibly more specific effects of religious coping on anxiety, and thus suggest possible differential effects of some aspects of religious coping strategies and practices on anxiety and depression. At any rate, the overall similarity in effects is not surprising, given the typical co-occurrence of anxiety and depressive symptoms throughout the lifespan (e.g., Beekman et al. 2000; Brady and Kendall 1992), which suggests a more general beneficial effect of using religious coping in reducing them and thus maintaining well-being. These findings are also consistent with the expectations of the current study, which was not designed to investigate differential effects of the coping aspects captured by our measures on anxiety and depression.

Caveats

While our study contributes novel evidence clarifying the associations and mechanisms of religious coping and its protective effect against symptoms of distress, it also has some limitations. First, our sample consisted mainly of younger adults (between 18 and 39 years old), representing undergraduate students and Urbana-Champaign community participants who responded to our study advertisements. However, to provide a more balanced representation of the studied phenomena across the whole spectrum of adulthood, and to increase the generalizability of the findings, future studies should also consider the inclusion of older adults. Second, only a small number of our participants (27%) reported details regarding their specific religious affiliation. These available data show diverse religious representations (i.e., Christianity, 65.5%; Atheism, 9.1%; Buddhism, 3.6%; Judaism, 3.6%; Agnostic, 1.8%; Agnostic Secular Humanistic, 1.8%; Apatheism, 1.8%; Pantheism, 1.8%; Protestantism, 1.8%; Taoism, 1.8%; Spiritual, 1.8%; and None 5.5%), consistent with the religious composition of adults in the Midwest. However, the likely homogeneity of religions represented in our study sample limits the generalizability of the present findings to other religions than Christianity. To increase generalizability of the findings, future studies should target a more balanced religious representation.

Conclusion

In summary, the present study fills an important gap in the literature regarding the mechanisms by which religiosity and religious coping are associated with positive outcomes of mental health. Overall, the present findings highlight the mediating role of reappraisal and coping self-efficacy in the protecting role of religious coping against anxiety and depression symptoms. These results provide novel scientific evidence further validating millennia-old traditional coping practices and shed light on psychological factors influencing adaptive behaviors that promote increased resilience, reduce symptoms of distress, and maintain emotional well-being. Hence, the present results inform both general counseling practices and counseling of religious clients. Specifically, professionals (e.g., clinicians) and paraprofessionals (e.g., clergy members) may use this evidence to encourage religious reappraisal and to specifically target the development of coping self-efficacy with their clients, whose spirituality and religiosity may be central to their healing, or with their congregations, whose faith may be central to their everyday life. Religious reappraisal and coping self-efficacy may, in turn, have beneficial effects reflected in reduced symptoms of distress and improved well-being and quality of life. Such positive outcomes are especially relevant when facing a crisis, such as the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic, as religious individuals may learn and apply helpful emotion regulation and coping strategies from therapy and other faith-based contexts to better manage everyday stress.

References

Austin, P., Macdonald, J., & MacLeod, R. (2018). Measuring spirituality and religiosity in clinical settings: A scoping review of available instruments. Religions, 9(3), 70.

Bandura, A. (2010). Self‐efficacy. The Corsini encyclopedia of psychology, 1–3.

Beck, A. T., Ward, C. H., Mendelson, M., Mock, J., & Erbaugh, J. (1961). An inventory for measuring depression. Archives of General Psychiatry, 4(6), 561–571.

Beekman, A. T., de Beurs, E., van Balkom, A. J., Deeg, D. J., van Dyck, R., & van Tilburg, W. (2000). Anxiety and depression in later life: Co-occurrence and communality of risk factors. American Journal of Psychiatry, 157(1), 89–95.

Benight, C. C., & Harper, M. L. (2002). Coping self-efficacy perceptions as a mediator between acute stress response and long-term distress following natural disasters. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 15(3), 177–186.

Brady, E. U., & Kendall, P. C. (1992). Comorbidity of anxiety and depression in children and adolescents. Psychological Bulletin, 111(2), 244.

Carver, C. S. (1997). You want to measure coping but your protocol’too long: Consider the brief cope. International Journal of Behavioral Medicine, 4(1), 92.

Carver, C. S., Scheier, M. F., & Weintraub, J. K. (1989). Assessing coping strategies: A theoretically based approach. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 56(2), 267.

Chesney, M. A., Neilands, T. B., Chambers, D. B., Taylor, J. M., & Folkman, S. (2006). A validity and reliability study of the coping self-efficacy scale. British Journal of Health Psychology, 11(3), 421–437.

Cieslak, R., Benight, C. C., & Lehman, V. C. (2008). Coping self-efficacy mediates the effects of negative cognitions on posttraumatic distress. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 46(7), 788–798.

Cornish, M. A., Lannin, D. G., Wade, N. G., & Martinez, M. (2017). Can use of positive religious coping predict greater distress? An examination of Army soldiers on deployment. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 64(3), 302.

Dolcos, S., Hu, Y., Iordan, A. D., Moore, M., & Dolcos, F. (2015). Optimism and the brain: Trait optimism mediates the protective role of the orbitofrontal cortex gray matter volume against anxiety. Social Cognitive and Affective Neuroscience, 11(2), 263–271.

Eliade, M. (1981). History of religious ideas (Vol. 1–3). Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Eliade, M. (1985). History of religious ideas (Vol. 1–3). Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Eliade, M. (1988). History of religious ideas (Vol. 1–3). Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Garssen, B., Uwland-Sikkema, N. F., & Visser, A. (2015). How spirituality helps cancer patients with the adjustment to their disease. Journal of Religion and Health, 54(4), 1249–1265.

Gross, J. J. (1998). The emerging field of emotion regulation: An integrative review. Review of General Psychology, 2(3), 271.

Gross, J. J., & John, O. P. (2003). Individual differences in two emotion regulation processes: Implications for affect, relationships, and well-being. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 85(2), 348.

Hayes, A. F. (2012). PROCESS: A versatile computational tool for observed variable mediation, moderation, and conditional process modeling: University of Kansas, KS.

Hu, Y., & Dolcos, S. (2017). Trait anxiety mediates the link between inferior frontal cortex volume and negative affective bias in healthy adults. Social Cognitive and Affective Neuroscience, 12(5), 775–782.

Israel-Cohen, Y., Kaplan, O., Noy, S., & Kashy-Rosenbaum, G. (2016). Religiosity as a moderator of self-efficacy and social support in predicting traumatic stress among combat soldiers. Journal of Religion and Health, 55(4), 1160–1171.

King, J. E., & Crowther, M. R. (2004). The measurement of religiosity and spirituality: Examples and issues from psychology. Journal of Organizational Change Management, 17(1), 83–101.

Llewellyn, N., Dolcos, S., Iordan, A. D., Rudolph, K. D., & Dolcos, F. (2013). Reappraisal and suppression mediate the contribution of regulatory focus to anxiety in healthy adults. Emotion, 13(4), 610.

Luberto, C. M., Cotton, S., McLeish, A. C., Mingione, C. J., & O’Bryan, E. M. (2014). Mindfulness skills and emotion regulation: The mediating role of coping self-efficacy. Mindfulness, 5(4), 373–380.

Maltby, J., & Day, L. (2003). Religious orientation, religious coping and appraisals of stress: Assessing primary appraisal factors in the relationship between religiosity and psychological well-being. Personality and Individual Differences, 34(7), 1209–1224.

Miller, L., & Kelley, B. S. (2005). Relationships of religiosity and spirituality with mental health and psychopathology. Handbook of the psychology of religion and spirituality, 460–478.

Moore, M., Culpepper, S., Phan, K. L., Strauman, T. J., Dolcos, F., & Dolcos, S. (2018). Neurobehavioral mechanisms of resilience against emotional distress: An integrative brain-personality-symptom approach using structural equation modeling. Personality Neuroscience, 1.

Pargament, K. I. (2001). The psychology of religion and coping: Theory, research, practice. New York: Guilford Press.

Pargament, K. I., Koenig, H. G., & Perez, L. M. (2000). The many methods of religious coping: Development and initial validation of the RCOPE. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 56(4), 519–543.

Park, C. L. (2013). Religion and meaning. In C. L. P. Raymond & F. Paloutzian (Eds.), Handbook of the psychology of religion and spirituality. New York: The Guilford Press.

Park, C. L., Smith, P. H., Lee, S. Y., Mazure, C. M., McKee, S. A., & Hoff, R. (2017). Positive and negative religious/spiritual coping and combat exposure as predictors of posttraumatic stress and perceived growth in Iraq and Afghanistan veterans. Psychology of Religion and Spirituality, 9(1), 13.

Peres, J. F., Moreira-Almeida, A., Nasello, A. G., & Koenig, H. G. (2007). Spirituality and resilience in trauma victims. Journal of Religion and Health, 46(3), 343–350.

Resick, P. A., Monson, C. M., & Rizvi, S. L. (2013). Posttraumatic stress disorder. Psychopathology: History, diagnosis, and Empirical Foundations, 244–284.

Sanz, J., & Paz Garcia-Vera, M. (2007). A psychometric analysis of the short forms of the 1978 version of the Beck Depression Inventory (BDI-IA). Psicologia Conductual, 15(2), 191–214.

Simonič, B., & Klobučar, N. R. (2017). Experiencing positive religious coping in the process of divorce: A qualitative study. Journal of Religion and Health, 56(5), 1644–1654.

Spielberger, C., Gorsuch, R., Lushene, R., Vagg, P., & Jacobs, G. (1970). State-trait anxiety inventory. Palo Alto: Consulting Psychologists Press.

Talik, E., & Skowroński, B. (2018). The sense of quality of life and religious strategies of coping with stress in prison inmates. Journal of Religion and Health, 1–23.

Thomas, E., & Savoy, S. (2014). Relationships between traumatic events, religious coping style, and posttraumatic outcomes. Traumatology: An International Journal, 20(2), 84.

Trevino, K. M., Archambault, E., Schuster, J., Richardson, P., & Moye, J. (2012). Religious coping and psychological distress in military veteran cancer survivors. Journal of Religion and Health, 51(1), 87–98.

Vasile, C. (2013). Homo religious—culture, cognition, emotion. Procedia - Social and Behavioral Sciences, 78, 658–661.

Vishkin, A., Bigman, Y. E., Porat, R., Solak, N., Halperin, E., & Tamir, M. (2016). God rest our hearts: Religiosity and cognitive reappraisal. Emotion, 16(2), 252.

Wallace, B. A., & Shapiro, S. L. (2006). Mental balance and well-being: Building bridges between Buddhism and Western psychology. American Psychologist, 61(7), 690.

Whisman, M. A., Perez, J. E., & Ramel, W. (2000). Factor structure of the Beck Depression Inventory—Second Edition (BDI-ii) in a student sample. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 56(4), 545–551.

Acknowledgements

This work was conducted at the Beckman Institute for Advanced Science and Technology at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign. The authors wish to thank members of the Dolcos Lab for assisting with data collection and Dr. Nathan Todd for providing comments on a previous version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was supported by funds from the University of Illinois.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

F.D. and S.D. conceived the study, S.D. contributed to data collection, F.D. and S.D. planned the analytical approach, Y.H., S.D., and K.H. performed the analyses, and K.H. and F.D. wrote the manuscript, with feedback from S.D.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethical Approval

The present research was performed in compliance with ethical standards regarding the treatment of human participants, and the experimental protocols were approved by the University’s Institutional Review Board.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Dolcos, F., Hohl, K., Hu, Y. et al. Religiosity and Resilience: Cognitive Reappraisal and Coping Self-Efficacy Mediate the Link between Religious Coping and Well-Being. J Relig Health 60, 2892–2905 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10943-020-01160-y

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10943-020-01160-y