Abstract

Participation in social behaviors that enhance group-level fitness may be influenced by mutations that affect patterns of social epistasis in human populations. Mutations that cause individuals to not participate in these behaviors may weaken the ability of members of a group to coordinate and regulate behavior, which may in turn negatively affect fitness. To investigate the possibility that de novo mutations degrade these adaptive social behaviors, we examine the effect of paternal age (as a well-established proxy for de novo mutation load) on one such social behavior, namely religious observance, since religiosity may be a group-level cultural adaptation facilitating enhanced social coordination. Using two large samples (Wisconsin Longitudinal Study and AddHealth), each of a different US birth cohort, paternal age was used to hierarchically predict respondent’s level of church attendance after controlling for multiple covariates. The effect is absent in WLS (β = .007, ns, N = 4560); however, it is present in AddHealth (β = − .046, p < .05, N = 4873) increasing the adjusted model R2 by .005. The WLS respondents were (mostly) born in the 1930s, whereas the AddHealth respondents were (mostly) born in the 1970s. This may indicate that social-epistatic regulation of behavior has weakened historically in the USA, which might stem from and enhance the ability for de novo mutations to influence behavior among more recently born cohorts—paralleling the secular rise in the heritability of age at sexual debut after the sexual revolution.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

It should be noted that the reality of group selection is a controversial matter (see Bahar 2018). Nevertheless, some of the most quantitatively sophisticated evolutionary theorists of recent times have provided a great deal of support for the view that group selection does operate, or at least has operated, in human populations (e.g., Bowles and Gintis 2011; Jones 2018; see also: Salter and Harpending 2013). Individual and gene-level selection theorists who oppose group-selection theories have failed to provide any compelling basis on which to doubt the results of such research, so we freely avail ourselves of the concept of group selection.

For molecular-genetic evidence of mutation accumulation in some European populations over many thousands of years, see Aris-Brosou (2019). But note that there is little reason to think that relaxed selection is relevant to the mutation accumulation detected except for that in “recent times” (Aris-Brosou 2019, p. 7), as mutation-accumulation theories stressing the role of industrialization would predict.

References

Aris-Brosou, S. (2019). Direct evidence of an increasing mutational load in humans. Molecular Biology and Evolution. https://doi.org/10.1093/molbev/msz192.

Arslan, R. C., Willführ, K. P., Frans, E., Verweij, K. J., Myrskylä, M., Voland, E., et al. (2017). Older fathers’ children have lower evolutionary fitness across four centuries and in four populations. Proceedings of the Royal Society B, 284, 20171562.

Bachmann, S. O., Cross, E., Kalbassi, S., Sarraf, M. A., Woodley of Menie, M. A., & Baudouin, S. J. (2018). Protein pheromone MUP20/Darcin is a vector and target of indirect genetic effects in mice. bioRxiv. https://doi.org/10.1101/265769.

Bahar, S. (2018). The essential tension: Competition, cooperation and multilevel selection in evolution. New York: Springer.

Baud, A., Mulligan, M. K., Casale, F. P., Ingels, J. F., Bohl, C. J., & Stegle, O. (2017). Genetic variation in the social environment contributes to health and disease. PLoS Genetics, 13, e1006498.

Bouchard, T. J., Jr. (2004). Genetic influence on human psychological traits. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 13, 148–151.

Bowles, S., & Gintis, H. (2011). A cooperative species: Human reciprocity and its evolution. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Boyer, P. (2001). Religion explained: The evolutionary origins of religious thought. New York: Basic Books.

Bradshaw, M., & Ellison, C. (2008). Do genetic factors influence religious life? Findings from a behavior genetic analysis of twin siblings. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion, 47, 529–544.

Chou, H. G., & Elison, S. (2014). Impact of birth order on religious behaviors among college students raised by highly religious Mormon parents. Archive for the Psychology of Religion, 36, 105–117.

Cohen, J. (1988). Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences (2nd ed.). Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Cross, E. S. R. (2019). Investigation of social olfaction in a Neuroligin 3 Knockout mouse model. Unpublished doctoral dissertation, School of Biosciences, Cardiff University, UK.

Dillon, M. (2003). Handbook of the sociology of religion. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Domingue, B. W., & Belsky, D. W. (2017). The social genome: Current findings and implications for the study of human genetics. PLoS Genetics, 13, e1006615.

Domingue, B. W., Belsky, D. W., Fletcher, J. M., Conley, D., Boardman, J. D., & Harris, K. M. (2018). The social genome of friends and schoolmates in the National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent to Adult Health. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, USA, 115, 702–707.

D’Onofrio, B. M., Rickert, M. E., Frans, E., Kuja-Halkola, R., Almqvist, C., Sjölander, A., et al. (2014). Paternal age at childbearing and offspring psychiatric and academic morbidity. JAMA Psychiatry, 71, 432.

Dunkel, C. S., Reeve, C. L., Woodley of Menie, M. A., & van der Linden, D. (2015). A comparative study of the general factor of personality in Jewish and non-Jewish populations. Personality and Individual Differences, 78, 63–67.

Dunne, M., Martin, N., Statham, D., Slutske, W., Dinwiddie, S., Bucholz, K., et al. (1997). Genetic and environmental contributions to variance in age at first sexual intercourse. Psychological Science, 8, 211–216.

Dutton, E., Madison, G., & Dunkel, C. (2018). The mutant says in his heart, “There is no God”: The rejection of collective religiosity centred around the worship of moral Gods is associated with high mutation load. Evolutionary Psychological Science, 4, 233–244.

Dutton, E., te Nijenhuis, J., Metzen, D., van der Linden, D., & Madison, G. (in press). The myth of the stupid believer: The negative religiousness-IQ nexus is not on general intelligence (g) and is likely a product of the relations between IQ and Autism Spectrum traits. Journal of Religion and Health. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10943-019-00926-3.

Dutton, E., & van der Linden, D. (2015). Who are the “Clever Sillies”? The intelligence, personality, and motives of clever silly originators and those who follow them. Intelligence, 49, 57–65.

Ellis, L., Hoskin, A. W., & Ratnasingam, M. (2016). Testosterone, risk taking, and religiosity: Evidence from two cultures. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion, 55, 153–173.

Faria, F. N. (2017). Is market liberalism adaptive? Rethinking F. A. Hayek on moral evolution. Journal of Bioeconomics, 19, 307–326.

Fieder, M., & Huber, S. (2015). Paternal age predicts offspring chances of marriage and reproduction. American Journal of Human Biology, 27, 339–343.

Figueredo, A. J., Vásquez, G., Brumbach, B. H., & Schneider, S. M. (2007). The K-factor, covitality, and personality. Human Nature, 18, 47–73.

Forbes, C. E., & Grafman, J. (2010). The role of the human prefrontal cortex in social cognition and moral judgment. Annual Review of Neuroscience, 33, 299–324.

Giosan, C. (2006). High-K strategy scale: A measure of the high-K independent criterion of fitness. Evolutionary Psychology, 4, 394–405.

Gorsuch, R. L. (1983). Factor analysis (2nd ed.). Hillsdale, NJ: L. Erlbaum Associates.

Henneberg, M., & Saniotis, A. (2009). Evolutionary origins of human brain and spirituality. Anthropologischer Anzeiger, 67, 427–438.

Herd, P., Carr, D., & Roan, C. (2014). Cohort profile: Wisconsin longitudinal study (WLS). International Journal of Epidemiology, 43, 34–41.

Huber, S., & Fieder, M. (2014). Advanced paternal age is associated with lower facial attractiveness. Evolution and Human Behavior, 35, 298–301.

Jack, A. I., Friedman, J. P., Boyatzis, R. E., & Taylor, S. N. (2016). Why do you believe in God? Relationships between religious belief, analytic thinking, mentalizing and moral concern. PLoS ONE, 11, e0149989.

Jones, D. (2018). Kin selection and ethnic group selection. Evolution and Human Behavior, 39, 9–18.

Kalbassi, S., Bachmann, S. O., Cross, E., Roberton, V. H., & Baudouin, S. J. (2017). Male and female mice 14 lacking Neuroligin-3 modify the behavior of their wild-type littermates. eNeuro, 4, 1–14.

Kendler, K. S., & Myers, J. (2009). A developmental twin study of church attendance and alcohol and nicotine consumption: A model for analyzing the changing impact of genes and environment. American Journal of Psychiatry, 166, 1150–1155.

Koenig, H. (2012). Religion, spirituality, and health: The research and clinical implications. ISRN Psychiatry. https://doi.org/10.5402/2012/278730.

Kondrashov, A. S. (2017). Crumbling genome: The impact of deleterious mutations on humans. Hoboken, NJ: Wiley.

Kutner, M., Nachtsheim, C., Neter, J., & Li, W. (2005). Applied linear statistical models (5th ed.). Irwin, CA: McGraw-Hill.

Lalumiere, M. L., Blanchard, R., & Zucker, K. J. (2000). Sexual orientation and handedness in men and women: A meta-analysis. Psychological Bulletin, 126, 575–592.

LaPiere, R. (1934). Attitudes and actions. Social Forces, 13, 230–237.

Linksvayer, T. A. (2007). Ant species differences determined by epistasis between brood and worker genomes. PLoS ONE, 2, e994.

Lynch, M. (2016). Mutation and human exceptionalism: Our future genetic load. Genetics, 202, 869–875.

MacDonald, K. B. (1994). A people that shall dwell alone: Judaism as a group evolutionary strategy. Westport, CT: Praeger.

Meisenberg, G., Rindermann, H., Patel, H., & Woodley, M. A. (2012). Is it smart to believe in God? The relationship of religiosity with education and intelligence. Temas em Psicologia, 20, 101–120.

Michaelson, J. J., Shi, Y., Gujral, M., Zheng, H., Malhotra, D., et al. (2012). Whole-genome sequencing in autism identifies hot spots for de novo germline mutation. Cell, 151, 1431–1442.

Moorjani, P. G., Gao, Z., & Przeworski, M. (2016). Human germline mutation and the erratic evolutionary clock. PLoS Biology, 14, e2000744.

Norenzayan, A., Gervais, W. M., & Trzesniewski, K. H. (2012). Mentalizing deficits constrain belief in a personal God. PLoS ONE, 7, e36880.

Norenzayan, A., & Sharif, A. (2008). The origin and evolution of religious pro-sociality. Science, 322, 58–62.

Norenzayan, A., Shariff, A. F., Gervais, W. M., Willard, A. K., McNamara, R. A., Slingerland, E., et al. (2016). The cultural evolution of prosocial religions. Behavioral and Brain Sciences, 39, 1–19.

Pew Research Center. (2015). Religious Landscape Study: Attendance at religious services by race/ethnicity. Retrieved from http://www.pewforum.org/religious-landscape-study/compare/attendance-at-religious-services/by/racial-and-ethnic-composition/. May 11.

Pietschnig, J., & Voracek, M. (2015). One century of global IQ gains: A formal meta-analysis of the Flynn effect (1909–2013). Perspectives on Psychological Science, 10, 282–306.

Piurko, Y., Schwartz, S. H., & Davidov, E. (2011). Basic personal values and the meaning of left-right political orientations in 20 countries. Political Psychology, 32, 537–561.

Rindermann, H. (2018). Cognitive capitalism: Human capital and the wellbeing of nations. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Rühli, F., & Henneberg, M. (2017). Biological future of humankind—Ongoing evolution and the impact of recognition of human biological variation. In M. Tibayrenc & F. J. Ayala (Eds.), On human nature: Biology, psychology, ethics, politics, and religion (pp. 263–275). London: Elsevier.

Salter, F. K., & Harpending, H. (2013). J.P. Rushton’s theory of ethnic nepotism. Personality and Individual Differences, 55, 256–260.

Sarraf, M. A., & Woodley of Menie, M. A. (2017). Of mice and men: Empirical support for the population-based social epistasis amplification model (a comment on Kalbassi et al., 2017). ENeuro, 4, e.0280–17.2017.

Sarraf, M. A., Woodley of Menie, M. A., & Feltham, C. (2019). Modernity and cultural decline: A biobehavioral perspective. New York, NY: Palgrave MacMillan.

Schmidt, F. L., & Hunter, J. E. (2015). Methods of meta-analysis: Correcting error and bias in research findings (3rd ed.). New York: SAGE Publications Inc.

Sela, Y., Shackelford, T., & Liddle, J. (2015). When religion makes it worse: Religiously motivated violence as a sexual selection weapon. In D. Sloane & J. Van Slyke (Eds.), The attraction of religion: A new evolutionary psychology of religion (pp. 111–132). London: Bloomsbury.

Simmel, G. (1957). Fashion. American Journal of Sociology, 62, 541–558.

Sulloway, F. J. (1998). Born to rebel: Birth order, family dynamics, and creative lives. London, UK: Abacus.

Teseo, S., Châline, N., Jaisson, P., & Kronauer, D. J. C. (2014). Epistasis between adults and larvae underlies caste fate and fitness in a clonal ant. Nature Communications. https://doi.org/10.1038/ncomms4363.

Turchin, P. (2016). Ages of discord: A structural-demographic analysis of American history. Chaplin, CT: Beresta Books.

Twenge, J. M., Honeycutt, N., Prislin, R., & Sherman, R. A. (2016). More polarized but more independent: Political party identification and ideological self-categorization among U.S. adults, college students, and late adolescents, 1970–2015. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 42, 1364–1383.

Wilson, D. S. (2002). Darwin’s cathedral: Evolution, religion, and the nature of society. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

Woodley of Menie, M. A., & Kanazawa, S. (2017). Paternal age negatively predicts offspring attractiveness in two, large, nationally representative datasets. Personality and Individual Differences, 106, 217–221.

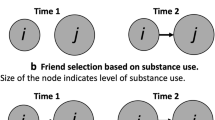

Woodley of Menie, M. A., Saraff, M., Pestow, R., & Fernandes, H. B. F. (2017). Social epistasis amplifies the fitness costs of deleterious mutations, engendering rapid fitness decline among modernized populations. Evolutionary Psychological Science, 3, 181–191.

Zuckerman, M., Li, C., & Lin, S. (2019). The negative intelligence–religiosity relation: New and confirming evidence. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin. https://doi.org/10.1177/0146167219879122.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Woodley of Menie, M.A., Kanazawa, S., Pallesen, J. et al. Paternal Age is Negatively Associated with Religious Behavior in a Post-60s But Not a Pre-60s US Birth Cohort: Testing a Prediction from the Social Epistasis Amplification Model. J Relig Health 59, 2733–2752 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10943-020-00987-9

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10943-020-00987-9