Abstract

Objectives

We used multilevel data from the National Crime Victimization Survey (NCVS) to identify factors that account for differences in risk of violent victimization among young Latino adults in new and traditional settlement areas.

Methods

Area-identified NCVS data (2008–2012) were linked with census tract data from the decennial census and American Community Survey to study individual and community contributions to the risk of violent victimization. We analyzed total violence and violence specific to offense types and victim-offender relationship. The analyses were performed adjusting for the complex survey design.

Results

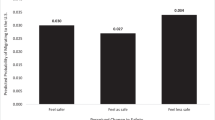

Young Latino adults in new settlement areas have higher victimization rates than their counterparts in traditional areas for total violence and for the majority of violence types studied. Holding constant individual and other contextual factors, Latino population density is a key neighborhood characteristic that explains the observed area differences in victimization, yielding evidence for the hypothesis that co-ethnic support in a community helps protect young Latino adults and contributes to differences in victimization across areas. Also there is evidence that the protective role of Latino population density is stronger for violence involving non-strangers than it is for violence involving strangers. Moreover, we find that the concentration of Latino immigrants, which indicates the neighborhood potential for immigrant revitalization, is another neighborhood factor that protects young Latino adults in both new and traditional settlement areas. However, there is some but limited evidence that the neighborhood-revitalizing role of immigration might be smaller in some contexts (such as some new areas outside central cities), possibly because those areas are heterogeneous in their ability to promote the integration of immigrants.

Conclusions

Our analysis of the NCVS shows the importance of neighborhood factors for the risk of violence among young Latino adults. It provides evidence consistent with co-ethnic support and immigrant revitalization theories. The findings also suggest that the effects of those neighborhood factors may be contingent upon violence type and the context in which they occur. These findings help us understand the difference in the safety of young Latino adults in new and traditional areas.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

Non-Latinos have a lower proportion of young adults in the 18-34 age group, and their victimization accounts for a lower proportion (43%) of violent victimization of non-Latinos (BJS 2015).

Non-Latinos did not show an elevation in victimization rates in new areas where Latinos have recently settled (Xie and Planty 2014). We focus on young Latino adults because their victimization rates vary greatly across settlement areas, and because they are at a critical stage for transitioning to mature adulthood, forming families, and achieving economic development. Understanding their victimization is crucial for understanding their social well-being.

The use of police crime statistics also means that the research is more prone to influences of victim reporting decisions and police investigatory and recording activities.

The two studies used different geographic units (counties vs. states) to define new areas of Latino settlement. These differences reflect the complexities of the definitions. For example, researchers may choose different geographic units (e.g., states vs. counties, cities, or metropolitan areas), or use different threshold values of Latino density and growth rates to define new settlement areas (see, e.g., discussion by Painter-Davis and Harris 2016; Suro and Singer 2002). These definitional differences reflect differences among studies in data sources, study period, and geographic coverage (see more discussion in “Data and Methods” section). Conceptually, however, these definitions are similar in that they all classify traditional areas as those that had a relatively large Latino presence before the geographic diversification of Latinos, and new areas as those that only in more recent years gained a substantial growth in the Latino population. As a result, these technical definitional differences are less stark than they initially appear (see, e.g., Xie and Planty’s (2014) comparison of two definitional schemes). The fact that studies have consistently found new settlement areas to have higher risks of victimization for Latinos despite definitional differences is in itself an important finding that marks new areas as an important ecological setting to be studied.

Other major causes of Latino growth in new communities, as noted, include the US immigration reform in the mid-1980s, selective hardening of the southern border, weakening labor demand in California, the passage of Proposition 187 in California, and the high Latino birth rate (Massey 2008).

Co-ethnic support has been used broadly in research on Latinos as a single group (e.g., Donthu and Cherian 1995; Waldinger 1989), as well as research on specific national groups, including Mexicans, Puerto Ricans, Cubans, South/Central Americans, and groups of other national origins (e.g., Logan et al. 2002). In this paper we focus on Latinos collectively because the NCVS uses the term in its basic screen questionnaire to describe people of Latino origin without distinguishing among Latino national groups. Hence, we exploit the NCVS data to its highest potential, though we also recognize the importance of distinctions regarding national origin, as we discuss in the concluding section of the paper.

A study of city crime rates, for example, may examine the cities’ history with regard to the lengths of Latino settlement and thus uses cities to define traditional and new settlement areas (see, e.g., Painter-Davis and Harris 2016).

Suro and Singer (2002) also defined “small” Latino areas that were characterized by both a small Latino base population and a small (or lack of) growth. Our analyses excluded those “small” areas because fewer than 10% of young Latino adults live in those areas and there are too few of them in the NCVS data for comparative analyses.

In a sensitivity analysis, we examined an alternative definition using Painter-Davis and Harris’ (2016) criteria to define new areas as counties whose Latino population comprised less than 10% of the county population in 1990 and that experienced at least a 50% increase in the Latino population from 1990 to 2000. This definition appears different as it considers data from 1990 to 2000, not from 1980 to 2010, but the definition had little impact for our analysis, because the two methods agreed on 90% of new counties and 96% of traditional counties, and the analysis yielded similar conclusions.

In 2000, “Latino foreign-born” is provided in the Census Summary File 3, table PCT63H, “Place of Birth by Citizenship Status (Hispanic or Latino).” In the American Community Survey, “Latino foreign-born” is provided in table B05003I, “Sex by Age by Nativity and Citizenship Status (Hispanic or Latino).”

In supplementary analyses, we also examined the interaction between new settlement area and regional dummies in order to detect if there are distinct victimization patterns in new settlement areas in different regions. We found that none of the interaction terms were statistically significant, whether or not the other control variables were included in the analyses. Future research may continue to explore regional patterns when there are more data available than the five years of data we have.

We explored the use of multilevel models in the analyses. In our data, a large proportion (16%) of census tracts had only one person-interview of young Latino adults during the study period, and close to half of census tracts (49%) had four or fewer person-interviews. This extremely low level of clustering makes the data unsuitable for testing random slope variances at the neighborhood level (Snijders and Bosker 1993), and thus we reported standard errors estimated using the NCVS design variables and weights to account for stratification, unequal probability of selection, and non-independence of observations due to the clustering of the data (Muthen and Satorra 1995).

Table 1 does not report robberies by non-strangers because such incidents were rare and the rates were unreliable, with coefficients of variation larger than 50%. We therefore focus on robberies by strangers.

In unreported analyses, for comparison purposes, we estimated the same set of models for non-Latino young adults, and found that (1) “new area” is not a risk factor for non-Latinos in any of the violence models, and (2) Latino population density is not a protective factor for non-Latinos in any forms of violence. These results indicate that new Latino settlement areas are distinctively dangerous for Latinos (not for non-Latinos). These findings strengthen the co-ethnic support argument.

The NCVS data that we use have too few observations of black or other non-white young Latino adults in new settlement areas (about only 4%) to allow us to examine Latinos separately by race. Such a comparison would necessitate pooling more years of data. Similarly, next steps include examining potential gender differences in victimization among Latinos across settlement type. Indeed, research has suggested that both gender and racial identities may shape the meanings and opportunities for violence (e.g., Kruttschnitt 2013; Tafoya 2007).

References

Alba RD, Logan JR, Bellair PE (1994) Living with crime: the implications of racial/ethnic differences in suburban location. Soc Forces 73:395–434

Aldrich HE, Waldinger R (1990) Ethnicity and entrepreneurship. Annu Rev Sociol 16:111–135

Barranco RE (2013) Latino immigration, interaction, and homicide victimization. Sociol Spectr 33:534–553

Block CR (1985) Race/ethnicity and patterns of Chicago homicide 1965 to 1981. Crime Delinq 31:104–116

Bloemraad I, Korteweg A, Yurdakul G (2008) Citizenship and immigration: multiculturalism, assimilation, and challenges to the nation-state. Annu Rev Sociol 34:153–179

Bonacich E (1993) The other side of ethnic entrepreneurship: a dialogue with Waldinger, Aldrich, Ward, and associates. Int Migrat Rev 27:685–692

Bureau of Justice Statistics (2015) Number of violent victimizations, 2008–2012. Table generated April 2015. NCVS Victimization Analysis Tool. www.bjs.gov

Bursik RJ Jr, Webb J (1982) Community change and patterns of delinquency. Am J Sociol 1:24–42

Cochran WG (1977) Sampling techniques. Wiley, New York

Cohen LE, Kluegel JR, Land KC (1981) Social inequality and predatory criminal victimization: an exposition and test of a formal theory. Am Sociol Rev 46:505–524

Conley M, Bohon S (2009) The spectrum’s other end: solidarity and distrust in a new Latino destination. J Latino Latin Am Stud 3:13–30

Covington J, Taylor RB (1989) Gentrification and crime: robbery and larceny changes in appreciating Baltimore neighborhoods during the 1970s. Urban Aff Q 25:142–172

Cranford CJ (2005) Networks of exploitation: immigrant labor and the restructuring of the Los Angeles janitorial industry. Soc Probl 52:379–397

Davis RC, Erez E, Avitabile N (2001) Access to justice for immigrants who are victimized: the perspectives of police and prosecutors. Crim Justice Policy Rev 12:183–196

Denham AC, Frasier PY, Hooten EG, Belton L, Newton W, Gonzalez P, Begum M, Campbell MK (2007) Intimate partner violence among Latinas in Eastern North Carolina. Violence Against Women 13:123–140

Desmond SA, Kubrin CE (2009) The power of place: immigrant communities and adolescent violence. Sociol Q 50:581–607

DiPietro SM, Bursik RJ (2012) Studies of the new immigration the dangers of pan-ethnic classifications. Ann Am Acad Polit Soc Sci 641:247–267

Donthu N, Cherian J (1995) Impact of strength of ethnic identification on Hispanic shopping behavior. J Retail 70:383–393

Dugan L, Apel R (2003) An exploratory study of the violent victimization of women: race/ethnicity and situational context. Criminology 41:959–979

Durand J, Telles E, Flashman J (2006) The demographic foundations of the Latino population. In: Tienda M, Mitchell F (eds) Hispanics and the future of America. The National Academies Press, Washington

Enriquez M, Kelly PJ, Cheng A, Hunter J, Mendez E (2012) An intervention to address interpersonal violence among low-income Midwestern Hispanic-American teens. J Immigr Minor Health 14:292–299

Feldmeyer B (2009) Immigration and violence: the offsetting effects of immigration on Latino violence. Soc Sci Res 38:717–731

Ferraro V (2016) Immigration and crime in the new destinations, 2000–2007: a test of the disorganizing effect of migration. J Quant Criminol 32:23–45

Fussell E (2011) The deportation threat dynamic and victimization of Latino migrants: wage theft and robbery. Sociol Q 52:593–615

Hagan J, Palloni A (1999) Sociological criminology and the mythology of Hispanic immigration and crime. Soc Probl 46:617–632

Hanson GH (2005) Market potential, increasing returns and geographic concentration. J Int Econ 67:1–24

Harknett K, McLanahan SS (2004) Racial and ethnic differences in marriage after the birth of a child. Am Sociol Rev 69:790–811

Harris CT, Feldmeyer B (2013) Latino immigration and White, Black, and Latino violent crime: a comparison of traditional and non-traditional immigrant destinations. Soc Sci Res 42:202–216

Hart TC, Rennison CM (2011) Violent victimization of Hispanic college students: findings from the National Crime Victimization Survey. Race Justice 1:362–385

Heitgerd JL, Bursik RJ Jr (1987) Extracommunity dynamics and the ecology of delinquency. Am J Sociol 92:775–787

Hindelang MJ, Gottfredson MR, Garofalo J (1978) Victims of personal crime: an empirical foundation for a theory of personal victimization. Ballinger, Cambridge

Hipp JR, Tita GE, Boggess LN (2009) Intergroup and intragroup violence: is violent crime an expression of group conflict or social disorganization? Criminology 47:521–564

Johnson KM, Lichter DT (2008) Natural increase: a new source of population growth in emerging Hispanic destinations in the United States. Popul Dev Rev 34:327–346

Kandel W, Cromartie J (2004) New patterns of Hispanic settlement in rural America. Economic Research Service, US Department Agriculture, Washington

Keely CB (1971) Effects of the immigration act of 1965 on selected population characteristics of immigrants to the United States. Demography 8:157–169

Kochhar R (2006) Latino labor report 2006: strong gains in employment. Pew Hispanic Center, Washington

Krivo LJ, Peterson RD (2000) The structural context of homicide: accounting for racial differences in process. Am Sociol Rev 65:547–559

Kruttschnitt C (2013) Gender and crime. Ann Rev Sociol 39:291–308

Kubrin CE (2014) Secure or insecure communities? Criminol Public Policy 13:323–338

Kubrin CE, Desmond SA (2015) The power of place revisited: why immigrant communities have lower levels of adolescent violence. Youth Violence Juv Justice 13:345–366

Kubrin CE, Herting JR (2003) Neighborhood correlates of homicide trends: an analysis using growth-curve modeling. Sociol Q 44:329–350

Langton L, Berzofsky M, Krebs C, Smiley-McDonald H (2012) Victimizations not reported to the police, 2006–2010 (NCJ 238536). Bureau of Justice Statistics, Washington

Lauritsen JL (2001) The social ecology of violent victimization: individual and contextual effects in the NCVS. J Quant Criminol 17:3–32

Lauritsen JL, Heimer K (2010) Violent victimization among males and economic conditions. Criminol Public Policy 9:665–692

Lauritsen JL, White NA (2001) Putting violence in its place: the influence of race, ethnicity, gender, and place on the risk for violence. Criminol Public Policy 1:37–60

Lauritsen JL, Owens JG, Planty M, Rand MR, Truman JL (2012) Methods for counting high-frequency repeat victimizations in the National Crime Victimization Survey (NCJ-237308). Bureau of Justice Statistics, Washington

Leach MA, Bean FD (2008) The structure and dynamics of Mexican migration to new destinations in the United States. In: Massey DS (ed) New faces in new places: the changing geography of American immigration. Russell Sage, New York

Lee MT, Martinez R (2009) Immigration reduces crime: an emerging scholarly consensus. Sociol Crime Law 13:3–16

Lee MT, Martinez R, Rosenfeld R (2001) Does immigration increase homicide? Sociol Q 42:559–580

Lichter DT, Johnson KM (2009) Immigrant gateways and Hispanic migration to new destinations. Int Migrat Rev 43:496–518

Light I, Gold SJ (2000) Ethnic economies. Academic Press, San Diego

Lobao LM, Hooks G (2007) Advancing the sociology of spatial inequality: spaces, places, and the subnational scale. In: Lobao LM, Hooks G, Tickamyer AR (eds) The sociology of spatial inequality. State University of New York Press, New York

Logan J, Zhang W, Alba RD (2002) Immigrant enclaves and ethnic communities in New York and Los Angeles. Am Sociol Rev 67:299–322

Lopez WD, Graham LF, Reardon C, Reyes AM, Reyes A, Padilla M (2012) No jobs, more crime. More jobs, less crime: structural factors affecting the health of Latino men in Detroit. J Men’s Health 9:255–260

Lynch JP, Addington LA (2007) Understanding crime statistics: Revisiting the divergence of the NCVS and the UCR. Cambridge University Press, New York

Martinez R (2002) Latino homicide: immigration, violence and community. Routledge, New York

Martinez R, Lee MT, Nielsen AL (2004) Segmented assimilation, local context and determinants of drug violence in Miami and San Diego: does ethnicity and immigration matter? Int Migrat Rev 38:131–157

Massey DS (2008) New faces in new places: the changing geography of American immigration. Russell Sage, New York

Massey DS, Capoferro C (2008) The geographic diversification of American immigration. In: Massey DS (ed) New faces in new places: the changing geography of American immigration. Russell Sage, New York

Menjívar C, Bejarano C (2004) Latino immigrants’ perceptions of crime and police authorities in the United States: a case study from the Phoenix metropolitan area. Ethnic Racial Stud 27:120–148

Michelson MR (2003) The corrosive effect of acculturation: how Mexican Americans lose political trust. Soc Sci Q 84:918–933

Moore J, Vigil JD (1993) Barrios in transition. In: Moore J, Pinderhughes R (eds) In the Barrios: Latinos and the underclass debate. Russell Sage, New York

Murdaugh C, Hunt S, Sowell R, Santana I (2004) Domestic violence in Hispanics in the Southeastern United States: a survey and needs analysis. J Fam Violence 19:107–115

Muthen BO, Satorra A (1995) Complex sample data in structural equation modeling. Sociol Methodol 25:267–316

Nelson C, Tienda M (1985) The structuring of Hispanic ethnicity: historical and contemporary perspectives. Ethnic Racial Stud 8:49–74

Oropesa RS, Lichter DT, Anderson RN (1994) Marriage markets and the paradox of Mexican American nuptiality. J Marriage Fam 56:889–907

Ottaviano GIP, Peri G (2006) The economic value of cultural diversity: evidence from US cities. J Econ Geogr 6:9–44

Ousey GC, Kubrin CE (2009) Exploring the connection between immigration and violent crime rates in US cities, 1980–2000. Soc Probl 56:447–473

Painter-Davis N, Harris CT (2016) Structural disadvantage and Latino violent offending: assessing the Latino paradox in context of established versus emerging Latino destinations. Race Justice 6:350–369

Parrado EA, Kandel W (2008) New Hispanic migrant destinations: a tale of two industries. In: Massey DS (ed) New faces in new places: the changing geography of American immigration. Russell Sage, New York

Perez DJ, Fortuna L, Alegria M (2008) Prevalence and correlates of everyday discrimination among U.S. Latinos. J Community Psychol 36:421–433

Peterson RD, Krivo LJ (2005) Macrostructural analyses of race, ethnicity, and violent crime: recent lessons and new directions for research. Ann Rev Sociol 31:331–356

Phillips JA (2002) White, Black, and Latino homicide rates: why the difference? Soc Probl 49:349–373

Phinney JS (1990) Ethnic identify in adolescents and adults: review of research. Psychol Bull 108:499–514

Portes A, Manning RD (1986) The immigrant enclave: theory and empirical examples. In: Olzak S, Nagel J (eds) Competitive ethnic relations. Academic Press, New York

Ramey DM (2013) Immigrant revitalization and neighborhood violent crime in established and new destination cities. Soc Forces 92:597–629

Rennison CM (2002) Hispanic victims of violent crime, 1993–2000. Bureau of Justice Statistics, Washington

Ruggles S, Alexander JT, Genadek K, Goeken R, Schroeder MB, Sobek M (2010) Integrated public use microdata series: Version 5.0 [Machine-readable database]. Minnesota Population Center, Minneapolis, MN

Sampson RJ (2008) Rethinking crime and immigration. Contexts 7:28–33

Sampson RJ, Bean L (2006) Cultural mechanisms and killing fields: a revised theory of community-level racial inequality. In: Peterson R, Krivo L, Hagan J (eds) The many colors of crime: Inequalities of race, ethnicity and crime in America. New York University Press, New York

Sampson RJ, Laub JH (1993) Crime in the making: pathways and turning points through life. Harvard University, Cambridge

Sampson RJ, Lauritsen JL (1994) Violent victimization and offending: Individual-, situational-, and community-level risk factors. In: Reiss AJ, Roth J (eds) Understanding and preventing violence: social influences. National Academy Press, Washington

Sampson RJ, Morenoff JD, Raudenbush SW (2005) Social anatomy of racial and ethnic disparities in violence. Am J Public Health 95:224–232

Shihadeh ES, Barranco RE (2010) Latino immigration, economic deprivation, and violence: regional differences in the effect of linguistic isolation. Homicide Stud 14:336–355

Shihadeh ES, Barranco RE (2013) The imperative of place: homicide and the new Latino migration. Sociol Q 54:81–104

Shihadeh ES, Winters L (2010) Church, place, and crime: Latinos and homicide in new destinations. Sociol Inquiry 80:628–649

Snijders TA, Bosker RJ (1993) Standard errors and sample sizes for two-level research. J Educ Behav Stat 18:237–259

Sorenson SB, Telles CA (1991) Self-reports of spousal violence in a Mexican-American and non-Hispanic white population. Violence Vict 6:3–15

Spener D, Bean FD (1999) Self-employment concentration and earnings among Mexican immigrants in the US. Soc Forces 77:1021–1047

Stowell JI, Martinez R (2009) Incorporating ethnic-specific measures of immigration in the study of lethal violence. Homicide Stud 13:315–324

Suro R, Singer A (2002) Latino growth in metropolitan America: changing patterns, new locations. Brookings Institution and Pew Hispanic Center, Washington

Suttles GD (1968) The social order of the slum. University of Chicago Press, Chicago

Tafoya S (2007) Shades of belonging: Latinos and racial identity. In: Rothenberg PS (ed) Race, class, and gender in the United States. Worth Publishers, New York

Tienda M, Mitchell F (2006) Hispanics and the future of America. National Academies Press, Washington

US Department of Labor (2012) The Latino labor force at a glance. https://www.dol.gov/_sec/media/reports/hispaniclaborforce/

Velez MB (2006) Toward an understanding of the lower rates of homicide in Latino versus Black neighborhoods: a look at Chicago. In: Peterson RD, Krivo LJ, Hagan J (eds) Many colors of crime: inequalities of race, ethnicity, and crime in America. New York University Press, New York

Velez MB (2009) Contextualizing the immigration and crime effect. Homicide Stud 13:325–335

Velez MB, Lyons CJ (2012) Situating the immigration and neighborhood crime relationship across multiple cities. In: Kubrin CE, Zatz MS, Martinez R (eds) Punishing immigrants: policy, politics, and injustice. New York University Press, New York

Velez-Ibanez C (1993) U.S. Mexicans in the borderlands: being poor without the underclass. In: Moore J, Pinderhughes R (eds) In the Barrios: Latinos and the underclass debate. Russell Sage, New York

Wadsworth T (2010) Is immigration responsible for the crime drop? An assessment of the influence of immigration on changes in violent crime between 1990 and 2000. Soc Sci Q 91:531–553

Waldinger R (1989) Structural opportunity or ethnic advantage? Immigrant business development in New York. Int Migrat Rev 23:48–72

Waldinger R (1993) The two sides of ethnic entrepreneurship: reply to Bonacich. Int Migrat Rev 27:692–701

Waldinger R, Lichter MI (2003) How the other half works: Immigration and the social organization of labor. University of California Press, Berkeley

Woolcock M (1998) Social capital and economic development: toward a theoretical synthesis and policy framework. Theory Soc 27:151–208

Xie M (2010) The effects of multiple dimensions of residential segregation on Black and Hispanic homicide victimization. J Quant Criminol 26:237–268

Xie M, Planty M (2014) Violent victimization in new and established Hispanic areas, 2007–2010 (NCJ-246311). Bureau of Justice Statistics, Washington

Zatz MS, Smith H (2012) Immigration, crime, and victimization: rhetoric and reality. Annu Rev Law Soc Sci 8:141–159

Zhou M (2007) Revisiting ethnic entrepreneurship: convergencies, controversies, and conceptual advancements. In: Portes A, DeWind J (eds) Rethinking migration: new theoretical and empirical perspectives. Berghahn Books, New York

Zúñiga V, Hernandez-Leon R (2005) New destinations: Mexican immigration in the United States. Russell Sage, New York

Acknowledgements

This research was funded by the National Institute of Justice, Office of Justice Programs, Department of Justice, Award No. 2012-R2-CX-0017. The opinions expressed in this manuscript are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of the Department of Justice.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Xie, M., Heimer, K., Lynch, J.P. et al. Why is the Victimization of Young Latino Adults Higher in New Areas of Settlement?. J Quant Criminol 34, 657–690 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10940-017-9350-0

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10940-017-9350-0