Abstract

There is little research on the control strategies used by the general public to self-manage gambling habits and avoid harmful consequences. The current study sought to identify the most common self-control strategies of people who gamble regularly, the characteristics of those who use them, and assess the effectiveness of limit-setting strategies in reducing gambling-related harm. We recruited a large sample (N = 10,054) of Canadian adults who reported gambling activity in the past 12 months. Participants completed a survey that assessed gambling habits, use of control strategies including quantitative limit setting, and gambling related harm. The most common control strategies were setting predetermined spending limits, tracking money spent, and limiting alcohol consumption. The number of self-control strategies used by gamblers was positively associated with gambling involvement, annual income, problem gambling severity and playing electronic gaming machines. Approximately 45% of respondents failed to adhere to self-determined quantitative limits for spending, frequency, and time spent gambling. People who stayed within their gambling limits were less likely to report harm even after controlling for other risk factors. However, the effectiveness of remaining within one’s personal spending limit decreased for those whose limits exceed $200CAN monthly. The findings support public health interventions that promote lower-risk gambling guidelines aimed at helping gamblers stay within spending, frequency and duration limits.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Most people who gamble experience little to no harms from their gambling activities. The prevalence of gambling disorder (American Psychiatric Association 2013) impacts a relatively small proportion of the general population—approximately 1–3% (Williams et al. 2012). About 4% to 10% of the population are individuals who frequently gamble (at least twice weekly) or report symptoms of gambling disorder (i.e., gambling-related harms) that lie beneath the clinical threshold (Welte et al. 2015). The lack of harm observed in most of the population raises the question of what protective factors may be present. Why do some people seem to be protected from harm? Researchers theorize that gamblers instinctively develop protective strategies to minimize harm from gambling. However, there are few empirical studies on protective or control strategies that people who gamble regularly use to avoid harm and prevent the development of a gambling disorder.

Setting time and monetary limits are key messages in most responsible gambling guidelines (Wohl et al. 2013; Currie et al. 2018). In a 2005 Canadian survey when asked to define ‘responsible gambling,’ the most common responses were not spending more than you can afford, setting a monetary budget, and setting a time limit (Turner et al. 2005). Most gamblers use personal monetary and time limits as control strategies (Auer and Griffiths 2013; Wiebe et al. 2005), however individuals with gambling problems are generally less successful in sticking to their limits (Moore et al. 2012). Furthermore, gamblers experiencing problems also tend to set higher monetary and frequency (days per month) limits than non-problem gamblers (Hing et al. 2017).

Australian researchers conducted an in-depth examination of different self-control strategies employed by people who gamble regularly recruited through media and treatment settings (Moore et al. 2012). The types of control strategies investigated ranged from different ways of avoiding gambling (e.g., hobbies, self-exclusion programs, thinking about the negative consequences) to ways of limiting harm while gambling (e.g., leave credit cards at home). Among the self-control strategies used by participants when gambling, the most common were setting a budget target, keeping track of money spent, and setting a time limit. The use of limit setting strategies was more common in gamblers experiencing problems. Auer and Griffiths conducted related research (2013) on a sample of 5,000 high intensity online gamblers. The use of voluntary spending limits led to gamblers spending significantly less money on a range of online games including casino games and poker (Auer and Griffiths 2013). Voluntary monetary limits were found to be more impactful in curbing both expenditure and duration of play than the setting of voluntary time limits, except for poker players where the opposite was true. Other research has explored novel ways of helping gamblers adhere to personal monetary limits through the use of personalized feedback and pop-up messages on gaming machines (Wohl et al. 2013; Hollingshead et al. 2019).

Although these studies provide data on the prevalence and potential benefits of self- control strategies there remains little evidence that links the setting of limits to reduced harm from gambling. We also know little about the characteristics of gamblers who use self-control strategies and how successful regular gamblers are at sticking to voluntary limits. The current investigation was designed to further advance knowledge on the impact of self-control strategies in preventing problem gambling. The objectives for this study were: (1) identify the most common self-control strategies used by gamblers; (2) assess the typical personal quantitative limits regular gamblers set for money spent, frequency of gambling, and time spent gambling; (3) determine how well gamblers stay within these limits and; (4) assess the effectiveness of self-control strategies in reducing gambling-related harm. To ensure a range of self-control strategies was present in the sample, we specifically recruited regular gamblers.

Method

Online Panel Recruitment

The poor response rates of traditional phone-based recruitment methods (Lee et al. 2015) have led many researchers to embrace newer technologies such as Amazon’s Mechanical Turk (MTurk) platform to recruit participants (Kim and Hodgins 2017). Several market research firms have also created pools of thousands of individuals who have agreed to be solicited for research surveys in return for some form of compensation—i.e., money or points that can be redeemed later (Göritz 2007). These online panels allow researchers to recruit a large sample of individuals meeting a specific user profile (in this case, regular gamblers) in a more cost-efficient way than traditional recruitment methods.

Participants

A large sample of regular gamblers was recruited from a pool of online panelists associated with the survey firm Leger360 as part of the Alberta Gambling Research Institute’s National Study on Gambling and Problem Gambling in Canada. Specific questions were added to the panel as part of an initiative to develop lower-risk gambling guidelines (Currie et al, 2018) to better understand the use of personal quantitative limits that people employ to reduce or prevent gambling related harms. The online panel platform, LegerWeb, ensures the recruited sample is geographically representative of the Canadian population. The initial screening questions identified active gamblers based on individuals reporting that they typically gambled once a month. Recruitment was open from August 15 to September 15, 2018 with a target of recruiting 10,000 active gamblers. Because participants self-selected to the study, the final sample was not expected to be representative of all gamblers in the general population. Indeed, we sought to recruit a large cohort of people who actively and regularly gamble. Thus it was expected that those at risk of gambling harms would be over represented in the sample.

Participants were paid $10CAN to complete the survey in addition to Leger’s standard panel participation incentives (monthly lottery draws for merchandise and points). A total of 10,199 respondents self-identified as active gamblers according to the screening question. However upon completion of the specific gambling items on the survey 145 reported no gambling activity in the past 12 months. These respondents were excluded from the analysis leaving a final sample of 10,054.

Survey Instrument

Participants completed an online questionnaire covering basic demographic questions as well as a range of topics related to gambling and substance use. For the current study our primary interest was the data collected on gambling activities, gambling-related harm, and the use of gambling control strategies such as limit setting. Information on gambling activities was collected using the Gambling Participation Instrument (Williams et al. 2016), a reliable and valid tool for assessing the intensity and breadth of gambling habits across the most common formats legally available to Canadians. Consistent with previous studies (Currie et al. 2017), we quantified gambling habits into typical monthly expenditure, percent of income spent on gambling (total expenditure/total household income), frequency (days in a typical month engaged in gambling to a maximum of 30 days), and duration (total time in minutes spent on all forms of gambling).

Gambling formats covered included lottery and raffle tickets, instant win lottery tickets, electronic gaming machines (EGMs; included slot machines, video lottery terminals, electronic racing machines, and other machine types), sports betting, casino table games, bingo, and other forms of gambling. Participants were prompted to report activities from both in-person and online versions of all assessed gambling formats. Research has shown that EGMs and casino gambling have a greater risk of harm and addiction compared to other forms of gambling (Breen and Zimmerman 2002; Welte et al. 2004; Hollingshead et al. 2019). Therefore, to identify gamblers who play these high risk games we employed a dichotomous coding scheme used in prior studies (Currie et al. 2017) in which type of gambler was collapsed into two categories: (1) “EGM/casino” which included persons who reported playing electronic gaming machines or casino games in the past 12 months, and; (2) “other” which included individuals who only played other forms of gambling such as lottery sports betting etc.

The total expenditure on all forms of gambling was estimated by summing the expenditures for the individual gambling formats. Both self-reported losses and wins were considered in the calculation of total expenditure. The percent of income spent on gambling was calculated by dividing the total expenditure for the month by the participant’s gross monthly household income (to a maximum of 100%). Frequency of gambling was also assessed separately for each gambling format. The original 7-point categorical scale used in the survey was converted to a quantitative scale to estimate number of gambling days each month (1–5 times/year = 0.25 days; 6–11 times/year = 0.5 days; 1 time/month = 1 day; 2–3 times/month = 2.5 days; once per week = 4 days; 2–6 times/week = 16 days, or; daily = 30 days). The maximum frequency of gambling was calculated by summing the frequency values for the individual gambling formats resulting in a value ranging from 0 to 30 times per month. Total duration of gambling was assessed by summing the estimated time spent each month playing the individual game types.

The Problem Gambling Severity Index (PGSI), a nine-item scale that assesses consequences and behavioural symptoms of problem gambling in the past 12 months, was used to measure problem severity and gambling-related harms. The PGSI has good internal consistency (α = 0.95 within the current sample) and test–retest reliability (Ferris et al. 2001; Currie et al. 2012). Problem gambling severity is captured in both the total PGSI score (range 0 to 27) and the categories defining non-problem, low-risk, and moderate-risk/problem gamblers (Currie et al. 2012). Additional analyses were conducted with a subset of PGSI items that focus on consequences only: feeling guilty, betting more than can afford, recognition of a problem, health problems, financial problems, being criticized by others, and borrowing money to gamble. Each consequence was scored dichotomously (0 = never; 1 = sometimes, most of the time, or almost always) with total harm estimated by summing the individual scores.

Participants were asked a series of questions designed to elicit information on different self-control strategies that gamblers may use to avoid harm. Some questions were modified from an Ontario gambling prevalence survey (Wiebe et al. 2005). Participants were asked if they tracked how much money they spend on gambling, how often they gamble, and how much time they spend gambling. Participants endorsing yes were asked if they tracked these dimensions on a daily, weekly, monthly, or annual basis. Participants were then asked if they used any of the gambling control strategies listed in Table 1. Use of the strategy was assessed with a 5-point Likert scale: never, rarely, sometimes, usually, or always. Participants who reported some use of the strategy were asked if the strategy was not at all, mildly, somewhat or very helpful. For the three strategies concerning limits on money spent, frequency, and time spent participants were asked to provide the typical quantitative limits used and whether they used this limit rarely, sometimes, usually or always.

Analyses

For objective #1, descriptive statistics were used to profile the most common self-control strategies used by gamblers and their perceived helpfulness in avoiding harm. Comparisons (demographics, types and intensity of gambling, problem gambling severity) were made across three groups of interest: (1) gamblers who reported never or only rarely using any self-control strategies; (2) gamblers who reported using at least one self-control strategy, and; (3) gamblers who used all three quantitative limits at least sometimes.

To address objectives #2 and #3, the gamblers who reported using personal limits for gambling frequency, expenditure, and duration were categorized according to the proximity of their limits to actual gambling behaviour (i.e., stayed within limit or exceeded limit). Gamblers were classified as exceeding their personal limit if their actual gambling activity was 10% over the average monthly expenditure, frequency and duration within the sample. For people who set a frequency limit, the threshold for staying within the limit was no more than 2 days over their personal limit. For expenditure, the threshold for staying within the limit was no more $100CAN over their limit and for duration the threshold was no more than 5 h per month over their limit. In consideration of the number of statistical tests used and the large sample size, the criteria for statistical significance was set at p < 0.01.

Results

The demographic and gambling profile of participants are shown in Table 2. As expected, the average level of gambling participation and problem gambling severity was much higher than the general Canadian population (Williams et al. 2012). In addition to having higher PGSI scores, the sample’s gambling habits in terms of monthly expenditure and days gambling were well above the Canadian general population averages (Currie and Casey 2007). Nonetheless, a range of problem severity was represented in the sample with 65% having a PGSI score of zero.

Use of the different self-control strategies is shown in Table 1. The most common strategy used was setting a predetermined spending limit in advance of gambling. The least common was limiting cannabis use (employed by 9% of the sample), although regular cannabis use was infrequent in the sample. The strategy judged most effective was keeping track of money spent. Overall, 28% of the sample reported using no strategies to control their gambling and; 6% of the sample used all seven strategies. Use of self-control strategies was more common in gamblers who scored in the moderate to problem range of the PGSI. However 9% of the nearly 1500 moderate-risk/problem gamblers in the sample did not use any of the quantitative limit strategies and 5% used no control strategy whatsoever. The average number of strategies used was 2.5 (SD 2.3) and median was 2. Among participants that reported using two or more strategies, the most common pair was keeping track of money and setting a predetermined monetary limit.

Characteristics Of Those Using Different Control Strategies

Participants who reported using no control strategy were more likely to be single, had a higher income, and lower PGSI scores compared to those who reported using at least one control strategy and gamblers who reported using quantitative limits for frequency, expenditure, and duration (see Table 3). The no control strategy use group also gambled less frequently each month, spent less money, and was less likely to play EGMs or casino games compared to the other groups. Gamblers who used personal limits for frequency, expenditure, and duration had the highest PGSI scores and overall gambling levels. To assess the relative contribution of demographic and gambling characteristics in predicting the use of self-control strategies, a linear regression model was constructed with total number of self-control strategies as the dependent variable and characteristics that emerged from the univariate analyses as being significant as the predictor variables (marital status, PGSI score, income, days gambled per month, and EGM/casino player). Because frequency of gambling and monthly expenditure were highly correlated, only frequency was used in the model. The overall model was significant (R2 = 0.18; F(4,9902) = 499.92; p < 0.001). With all predictors in the model, use of self-control strategies was associated with a higher PGSI score, lower annual income, greater number of days gambled per month, and playing EGM or casino games (all ps < 0.001).

Typical Limits for Frequency, Expenditure, and Duration Set by Gamblers

Table 4 displays the personal limits used by gamblers. The expenditure limit was highly skewed; the mean limit was $231CAN whereas the median was under $70CAN. Similarly, the average duration limit was 23 h per month and the median was 9 h. Also shown in Table 4 is the actual gambling behaviour of the individuals who reported setting limits. A large discrepancy was detected between the self-determined limits and actual spending, frequency and duration. Notably, the average expenditure per month was over four times higher than the average self-determined spending limit. The difference between the median spending limit and actual spending was less pronounced but still showed a twofold difference. Similar discrepancies were evident for frequency and duration. Despite these discrepancies, most gamblers (55–58%) stayed close to their personal limits.

The effectiveness of limit setting was assessed by first exploring whether gamblers who remained close to their self-determined limits rated the limit setting strategy as more helpful compared to gamblers who exceeded their limits. Ratings of the helpfulness of setting a spending limit were significantly higher among gamblers who stayed close to their self-defined spending limit compared to gamblers who regularly exceeded their limit. (Mann–Whitney U test = 4,044,576, p < 0.005). Setting a frequency limit was also rated as more helpful for gamblers who remained close to their frequency limit (Mann–Whitney U test = 1,093,362, p < 0.005). There was no significant difference in ratings of the helpfulness of setting a duration limit between gamblers who stayed close to their time limit compared to gamblers who exceeded their limit (Mann–Whitney U test = 2,052,978, p > 0.01).

The impact of staying close to one’s personal monetary and frequency limits on gambling harm was tested via linear regression with total PGSI-defined harms (0–7) as the dependent variable. In the first model, covariates included exceeding one’s monetary limit by $100, age, gender, and playing EGMs or casino games. The overall model was significant (R2 = 0.21; F(4,5622) = 362.43, p < 0.001) all covariates were highly significant (p < 0.001). Exceeding one’s monetary limit by more than $100 was predictive of higher PGSI scores (t = 10.43, p < 0.001), even after controlling for age, gender, and playing EGMs or casino games. The same result was found when exceeding one’s frequency limit by 2 days was used as a predictor along with the same covariates. The overall model was significant (R2 = 0.24; F(4,2868) = 226.71, p < 0.001) and exceeding one’s frequency limit was predictive of more gambling harm (t = 5.59, p < 0.001) after controlling for other risk factors.

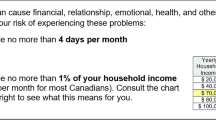

To assess whether exceeding ones spending limit conveys an even greater risk of harm for gamblers who set higher than average personal limits, a 2 × 2 ANOVA was conducted on total harms as the dependent variable. The between-subjects factors consisted of spending over $100 of one’s self-determined limit (yes/no) and setting a monthly personal spending limit of $200 or more (yes/no). To control for wealthier individuals having the financial means to set higher spending limits, income was used as a covariate in the model. As predicted the model produced a significant interaction effect, F(1,5157) = 7.02, p < 0.001. As shown graphically in Fig. 1, gamblers who set a personal spending limit of $200 or more had significantly more gambling harms if they exceeded this limit in actual spending compared to gamblers who exceeded a lower set limit.

Impact of exceeding personal spending limit by $100CAN or more for gamblers who set spending limit at more than $200 compared to gamblers who set limit below $200CAN. Difference in slopes significant (p < .001). Means adjusted for household income of participants. Standard error of the mean (95% confidence interval) shown

Discussion

The present study advances our understanding of the control strategies used by regular gamblers to prevent harm. In recent years, researchers have argued for greater attention to the notion of gambling-related harm in the population (Delfabbro and King 2019) rather than the prevalence and correlates of problem gambling, which only accounts for a very small segment of the general public. Recent estimates are that 85% of all gambling-related harm occurs in gamblers classified as low to moderate risk according to screening tools such as a PGSI (Delfabbro and King 2017). Because responsible gambling initiatives target all gamblers, it is important to have a better understanding of the self-control strategies used by individuals who are below the threshold for problem gambling. Consistent with other investigations (Auer and Griffiths 2013; Moore et al. 2012; Abbott et al. 2014), the most common self-control strategies centered on tracking and limiting money spent. These strategies were also rated as the most effective, along with limiting alcohol use. Most respondents used at least two strategies and 6% used all the strategies presented as response options in the survey. Paradoxically, use of more control strategies was associated with a higher problem gambling severity, a result also found in a recent Australian study of regular gamblers (Hing et al. 2017). It is possible that gamblers with greater problems attempt more control strategies out of necessity in that their gambling problems would be even greater if they used fewer control strategies. Further analysis revealed that adhering to self-determined quantitative limits for expenditure and frequency of gambling was associated with less harm. That is, the impact of setting quantitative limits for gambling activity is improved if one stays within these limits. Nonetheless, the value of staying within a personal limit is greatly diminished if the limit is set too high. This is not a surprising finding; a person who routinely stays within a personal limit of 6 alcoholic drinks per day will still be at a higher risk of harm than someone who stays within a personal limit of 2 drinks per day.

Without the benefit of longitudinal data on control strategy use, it is difficult to conclude that sticking to a quantitative limit results in a decrease in problem gambling severity over time. However, consistent with this notion, an investigation using longitudinal Canadian cohort data found that gamblers shifting from low-risk to high-risk spending (defined as spending more than $1000CAN annually on gambling) were more than two and half times more likely to experience future gambling harm compared to gamblers who remained at low-risk spending levels (Currie et al. 2011). This earlier study, combined with the present results, provides support for the need of evidence-based limits on spending, frequency, and time spent to guide gambling choices. The usefulness of predetermined limits on spending, frequency, and time was dependent on how well gamblers stayed close to their limits. Nonetheless, many active gamblers set personal limits on spending that exceed the typical gambling expenditure of adults in the general population. Furthermore, 45% of gamblers in the present study spent more than $100 over their own limit. An Australian research team also found that exceeding one’s personal spending limit was more common at higher spending levels (Rodda et al. 2019a). Without appropriate benchmarks on what constitutes low-risk spending, gamblers may set improperly defined limits. The same research team investigated the feasibility of providing a brief in-venue intervention to EGM gamblers to help them stay within their personal expenditure limit during their current venue visit (Rodda et al. 2019b). Importantly, this psychoeducational intervention was both feasible and associated with less expenditure at a 30-day follow-up. This study illustrates the potential value of helping individuals set and achieve reasonable personal limits.

While the current study affirms the value of setting quantitative limits on gambling intensity, it by no means diminishes the value of other strategies gamblers use to limit harm while gambling. Our assessment predominately focused on control strategies that gamblers could use while gambling. Limiting alcohol consumption and restricting access to cash were also rated as helpful control strategies. Other research teams (Moore et al. 2012) have found that gamblers also use preventative strategies to keep from gambling (e.g., pursue other leisure interests) and minimize harm when not gambling (e.g., avoid borrowing money from friends and family to gamble). A related investigation, which also targeted active gamblers, revealed a comprehensive list of ways that gamblers attempt to minimize harm (Rodda et al. 2018). Several strategies were variations of restricting access to money such as only bringing to the venue the amount of cash that one is prepared to spend, the most endorsed strategy overall, and leaving credit and bank cards at home.

A significant strength of this study is the large sample of adults who provided information on the control strategies of regular gamblers. The sample, while not randomly selected, was geographically representative of Canada and included a range of problem gambling severity including a large proportion of participants scoring zero on the PGSI. Nonetheless, we acknowledge the sample cannot be viewed as representative of the general population. As expected, both gambling activity and average PGSI score were much higher than those reported in Canadian epidemiological studies (Williams et al. 2012). As such, prevalence of control strategy use cannot be inferred from the results. The self-selected nature of the sample is a defendable limitation given our goal was to profile the harm reduction strategies of people who gamble regularly. Information from non-gamblers, or highly infrequent gamblers (e.g., occasional lottery players) would be of little value because this group would be unlikely to use any control strategies. This was evident in our subsample of gamblers who reported no control strategies. This group had an average PGSI score of less than one and only a small proportion played high-risk games such as EGMs.

Self-reported gambling activity is often criticized as being inaccurate and prone to underreporting, particularly losses. Although we could not validate gambler’ self-reports in the current study, the survey did employ the recommended survey methodology and question wording that produces the most accurate gambling activity (Williams et al. 2016). There is also evidence that participants are more forthcoming with computerized surveys than face-to-face interviewing with sensitive topics such as addictions (van der Heijden et al. 2000; Lee et al. 2015). Recruitment of participants using online panel pools has many other advantages. In addition to being less costly overall, we were able to recruit over 10,000 gamblers in one month. A comparably sized sample from the general population using traditional phone recruitment would typically take much longer and yield a very small proportion (< 5%) of moderate risk/problem gamblers. A disadvantage of the method is the lack of control that researchers have over the circumstances in which participants complete the survey (e.g., time of day, absence of other distractions). We also recognize this sample would be more computer literate than gamblers in the general population.

This is the first empirical investigation to demonstrate that effective use of control strategies, particularly the use the money and frequency limits, is associated with less gambling harm. Although prior studies associated limit setting with lower overall expenditure (Auer and Griffiths 2013) and fewer losses (Hing et al. 2017), these studies failed to establish a connection to less harm. The present findings have several practical implications for responsible gambling initiatives. Although there is validity to the common message of ‘set a limit and stick to it,’ the absence of any guideline on the size of the limit diminishes its overall effectiveness. The effectiveness of remaining with $100 of your self-determined spending limit decreases for gamblers whose limits exceed $200 monthly, an effect that was independent of household income. Furthermore, it appears that 9% of problem gamblers do use any limit setting strategies. There is clearly a need for more specific limits on spending, frequency, and duration to help the general public make safe choices when gambling. An ongoing Canadian research project is exploring the feasibility of low-risk gambling limits, akin to the low-risk drinking limits that are in place in many Western countries (Currie et al. 2018). Using both Canadian and international data, the project should establish evidence-based, quantitative limits on gambling behaviour to help people make informed decisions about their gambling.

References

Abbott, M. W., Bellringer, M., Garrett, N., & Mundy-McPherson, S. (2014). New Zealand 2012 National Gambling Study: Gambling harm and problem gambling (Report No.2). Auckland: Gambling and Addictions Research Centre.

American Psychiatric Association. (2013). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (5th ed.). Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association.

Auer, M., & Griffiths, M. D. (2013). Voluntary limit setting and player choice in most intense online gamblers: An empirical study of gambling behaviour. Journal of Gambling Studies,29(4), 647–660.

Breen, R. B., & Zimmerman, M. (2002). Rapid onset of pathological gambling in machine gamblers. Journal of Gambling Studies,18(1), 31–43.

Currie, S., & Casey, D. M. (2007). Quantification and dimensionalization of gambling behaviour. In G. Smith, D. C. Hodgins, & R. J. Williams (Eds.), Research and measurement issues in gambling studies (pp. 156–173). Burlington, MA: Academic Press.

Currie, S., Hodgins, D. C., Casey, D. M., El-Guebaly, N., Smith, G., Williams, R. J., et al. (2017). Deriving low-risk gambling limits from longitudinal data collected in two independent Canadian studies. Addiction,112(1), 2011–2020.

Currie, S. R., Hodgins, D. C., Casey, D., el-Guebaly, N., Smith, G., Williams, R. J., et al. (2011). Examining the predictive validity of low risk gambling limits with longitudinal data. Addiction,107(2), 400–406.

Currie, S. R., Hodgins, D. C., & Casey, D. (2012). Validity of the problem gambling severity index interpretive categories. Journal of Gambling Studies,29(2), 311–327.

Currie, S. R., Flores-Pajot, M. C., Hodgins, D., Nadeau, L., Paradis, C., Robillard, C., et al. (2018). A research plan to define Canada's first low-risk gambling guidelines. Health Promotion International. https://doi.org/10.1093/heapro/day074.

Delfabbro, P., & King, D. (2017). Prevention paradox logic and problem gambling: Does low-risk gambling impose a greater burden of harm than high-risk gambling? Journal of Behavioral Addictions,6(2), 163–167.

Delfabbro, P., & King, D. (2019). Challenges in the conceptualisation and measurement of gambling-related harm. Journal of Gambling Studies,35(3), 743–755.

Ferris, J., & Wynne, H. J. (2001). The Canadian Problem Gambling Index final report. Ottawa, ON: Canadian Centre on Substance Abuse.

Göritz, A. S. (2007). Using online panels in psychological research. In A. N. Joinson, K. McKenna, T. Postmes, & U.-D. Reips (Eds.), The Oxford handbook of internet psychology (pp. 473–486). New York: Oxford University Press.

Hing, N., Sproston, K., Tran, K., & Russell, A. M. T. (2017). Gambling responsibly: Who does it and to what end? Journal of Gambling Studies,33(1), 149–165. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10899-016-9615-9.

Hollingshead, S. J., Wohl, M. J. A., & Santesso, D. (2019). Do you read me? Including personalized behavioral feedback in pop-up messages does not enhance limit adherence among gamblers. Computers in Human Behavior,94(1), 122–130. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2019.01.015.

Kim, H. S., & Hodgins, D. C. (2017). Reliability and validity of data obtained from alcohol, cannabis, and gambling populations on Amazon's Mechanical Turk. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors,31(1), 85–94. https://doi.org/10.1037/adb0000219.

Lee, C.-K., Back, K.-J., Williams, R. J., & Ahm, S.-S. (2015). Comparison of telephone RDD and online panel survey modes on CPGI scores and comorbidities. International Gambling Studies,15(3), 435–449.

Moore, S. M., Thomas, A. C., Kyrios, M., & Bates, G. (2012). The self-regulation of gambling. Journal of Gambling Studies,28(3), 405–420.

Rodda, S. N., Bagot, K. L., Manning, V., & Lubman, D. I. (2018). 'Only take the money you want to lose' strategies for sticking to limits in electronic gaming machine venues. International Gambling Studies.. https://doi.org/10.1080/14459795.2019.1617330.

Rodda, S. N., Bagot, K. L., Manning, V., & Lubman, D. I. (2019a). "It was terrible. I didn't set a limit": Proximal and distal prevention strategies for reducing the risk of a bust in gambling venues. Journal of Gambling Studies. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10899-019-09829-0.

Rodda, S. N., Bagot, K. L., Manning, V., & Lubman, D. I. (2019b). An exploratory RCT to support gamblers’ intentions to stick to monetary limits: A brief intervention using action and coping planning. Journal of Gambling Studies. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10899-019-09873-w.

Turner, N. E., Wiebe, J., Falkowski-Ham, A., Kelly, J., & Skinner, W. (2005). Public awareness of responsible gambling and gambling behaviours in Ontario. International Gambling Studies,5(1), 95–112.

van der Heijden, P. G. M., van Gils, G., Bouts, J., & Hox, J. J. (2000). A comparison of randomized response, computer-assisted self-interview, and face-to-face direct questioning: Eliciting sensitive information in the context of welfare and unemployment benefit. Sociological Methods & Research,28, 505–537.

Welte, J., Barnes, G., Wieczorek, W., Tidwell, M., & Parker, J. (2004). Risk factors for pathological gambling. Addictive Behaviors,29(2), 323–335.

Wiebe, J., Mun, P., & Kauffman, N. (2005). Gambling and problem gambling in Ontario 2005. Toronto, ON: Responsible Gambling Council.

Welte, J. W., Barnes, G. M., Tidwell, M. C., Hoffman, J. H., & Wieczorek, W. F. (2015). Gambling and problem gambling in the United States: Changes between 1999 and 2013. Journal of Gambling Studies,31(3), 695–715.

Williams, R. J., Volberg, R., & Stevens, R. A. (2012). The population prevalence of problem gambling: methodological influences, standardized rates, jurisdictional differences, and worldwide trends. Report prepared for the Ontario Problem Gambling Research Centre and the Ontario Ministry of Health and Long Term Care. Alberta: University of Lethbridge.

Williams, R. J., Volberg, R. A., Stevens, R. M. G., Williams, L. A., & Arthur, J. N. (2016). The definition, dimensionalization, and assessment of gambling participation Lethbridge. Alberta: Canadian Consortium for Gambling Research.

Wohl, M. J. A., Gainsbury, S., Stewart, M. J., & Sztainert, T. (2013). Facilitating responsible gambling: The relative effectiveness of education-based animation and monetary limit setting pop-up messages among electronic gaming machine players. Journal of Gambling Studies,29(4), 703–717.

Funding

Study was funded by La foundation Mise sur toi, an independent non-profit organization based in Montreal, Canada. The contents of this paper are the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of the funder.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors contributed to the study conception and design. The first draft of the manuscript was written by Shawn Currie and all authors commented on previous versions of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

Currie [Consulting Fees: Canadian Centre on Substance Use and Addiction]. Nadeau [Consulting Fees: Canadian Centre on Substance Use and Addiction]. Hodgins [Grants/Research Support: CIHR; AGRI; Ministry of Health, New Zealand; Ontario Ministry of Health and Long-term Care, Ontario; Manitoba Gambling Research Program. Speakers Bureau/Honoraria: Conference travel funds New Horizons, Health Management Systems of America, Gambling International Symposium, Switzerland, V Congresso Clinca Psiquitria, Brazil, NCRG, Las Vegas, Responsible Gambling Council, Toronto. Consulting Fees: Canadian Centre on Substance Use and Addiction. Other: Partial salary support from the Alberta Gambling Research Institute]. Brunelle [Consulting Fees: Canadian Centre on Substance Use and Addiction.Grants/Research Support: Fonds de recherche Société et culture Québec (FRQSC), Quebec Ministry of Health (Ministère de la santé du Québec); Consulting Fees: Canadian Centre on Substance Use and Addiction]. Flores-Pajot, Brunelle, Dufour and Young have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Ethics information

The method described in the paper relies on secondary analyses of an existing dataset.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Currie, S.R., Brunelle, N., Dufour, M. et al. Use of Self-control Strategies for Managing Gambling Habits Leads to Less Harm in Regular Gamblers. J Gambl Stud 36, 685–698 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10899-019-09918-0

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10899-019-09918-0