Abstract

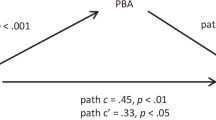

Specific phobias are among the most prevalent anxiety disorders in children and adolescents. Although brief and intensive treatments are evidence-based interventions (Davis III et al. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology, 15, 233–256, 2019), up to one-third of youth do not show significant change in their symptoms following these interventions. Hence, consideration of additional factors influencing treatment response is necessary. Child-factors such as temperament and parent-factors such as parenting behaviors both contribute to the development of specific phobias and their maintenance over time. Specifically, we addressed child temperament (negative affectivity) and parenting behaviors (overprotection) that could uniquely predict clinical outcomes for specific phobias and that might interact to inform goodness-of-fit in the context of these interventions. We also considered whether child- and/or parent-gender shaped the effects of temperament or parenting on clinical outcomes. Participants were 125 treatment-seeking youth (M age = 8.80 years; age range = 6–15 years; 51.5% girls) who met criteria for specific phobia and their mothers and fathers. Mothers’ reports of children’s negative affectivity uniquely predicted poorer specific phobia symptom severity and global clinical adjustment at post-treatment. Interaction effects were supported between parental overprotection and child negative affectivity for post-treatment fearfulness. The direction of these effects differed between fathers and mothers, suggesting that goodness-of-fit is important to consider, and that parent gender may provide additional nuance to considerations of parent-child fit indices.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

McDonald’s omega, rather than Cronbach’s alpha, was used to determine internal consistencies in the current study. This coincides with a broader shift in the field away from alphas, which depend on a larger set of assumptions that are typically not met with many measures (i.e., unidimensionality, sensitity of items), and biased estimated when assumptions are violated. Omega estimates incorporate fewer assumptions and show attenuated biases relative to alphas (see Dunn et al. 2014).

CGAS scores from 41 to 50 indicate moderate impairment in functioning in most domains and severe impairment in at least one domain, such as communication. CGAS scores from 81 to 90 indicate adequate functioning in all areas (see Wagner et al. 2007).

References

American Psychiatric Association. (1994). Statistical manual of mental disorders, (DSM-IV). Washington D.C.: American Psychiatric Association.

American Psychiatric Association (APA). (2013). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (5th ed.). Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Association.

Arcus, D., & Kagan, J. (1995). Temperament and craniofacial variation in the first two years. Child Development, 66, 1529–1540. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8624.1995.tb00950.x.

Bögels, S., & Phares, V. (2008). Fathers' role in the etiology, prevention and treatment of child anxiety: A review and new model. Clinical Psychology Review, 28, 539–558. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2007.07.011.

Bögels, S. M., & van Melick, M. (2004). The relationship between child-report, parent self-report, and partner report of perceived parental rearing behaviors and anxiety in children and parents. Personality and Individual Differences, 37, 1583–1596. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2004.02.014.

Bögels, S., Stevens, J., & Majdandžić, M. (2011). Parenting and social anxiety: Fathers’ versus mothers’ influence on their children’s anxiety in ambiguous social situations. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 52, 599–606. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-7610.2010.02345.x.

Booker, J. A., Capriola-Hall, N. N., Dunsmore, J. C., Greene, R. W., & Ollendick, T. H. (2018). Change in maternal stress for families in treatment for their children with oppositional defiant disorder. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 27, 2552–2561. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10826-018-1089-1.

Brody, L. R., & Hall, J. A. (1993). Gender and emotion in context. In M. Lewis, J. M. Haviland, & L. F. Barrett (Eds.), Handbook of emotions (pp. 89–121). New York: Guilford.

Capriola, N. N., Booker, J. A., & Ollendick, T. H. (2017). Profiles of temperament among youth with specific phobias: Implications for CBT outcomes. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 45, 1449–1459. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10802-016-0255-4.

Creswell, C., Willetts, L., Murray, L., Singhal, M., & Cooper, P. (2008). Treatment of child anxiety: An exploratory study of the role of maternal anxiety and behaviours in treatment outcome. Clinical Psychology & Psychotherapy: An International Journal of Theory & Practice, 15, 38–44. https://doi.org/10.1002/cpp.559.

Davis III, T. E., Ollendick, T. H., & Öst, L.-G. (2019). One-session treatment of specific phobias in children: Recent developments and a systematic review. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology, 15, 233–256.

De Pauw, S. S., & Mervielde, I. (2011). The role of temperament and personality in problem behaviors of children with ADHD. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 39, 277–291.

De Schipper, J. C., Tavecchio, L. W. C., Van Ijzendoorn, M. H., & Van Zeijl, J. (2004). Goodness-of-fit in center day care: Relations of temperament, stability, and quality of care with the child’s adjustment. Early Childhood Research Quarterly, 19, 257–272. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecresq.2004.04.004.

Degnan, K. A., & Fox, N. A. (2007). Behavioral inhibition and anxiety disorders: Multiple levels of a resilience process. Development and Psychopathology, 19, 729–746. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0954579407000363.

Dunn, T. J., Baguley, T., & Brunsden, V. (2014). From alpha to omega: A practical solution to the pervasive problem of internal consistency estimation. British Journal of Psychology, 105, 399–412. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjop.12046.

Dunsmore, J. C., Booker, J. A., Ollendick, T. H., & Greene, R. W. (2016). Emotion socialization in the context of risk and psychopathology: Maternal emotion coaching predicts better treatment outcomes for emotionally labile children with oppositional defiant disorder. Social Development, 25, 8–26. https://doi.org/10.1111/sode.12109.

Ellis, L. K., & Rothbart, M. K. (2001, April). Revision of the early adolescent temperament questionnaire. Poster presented at the 2001 Biennial Meeting of the Society for Research in child development, Minneapolis, Minnesota.

Essau, C. A., Conradt, J., & Petermann, F. (2000). Frequency, comorbidity, and psychosocial impairment of specific phobia in adolescents. Journal of Clinical Child Psychology, 29, 221–231. https://doi.org/10.1207/S15374424jccp2902_8.

Festen, H., Hartman, C. A., Hogendoorn, S., de Haan, E., Prins, P. J. M., Recichart, C. G., & Nauta, M. H. (2013). Temperament and parenting predicting anxiety change in cognitive behavioral therapy. Journal of Anxiety Disorders, 27, 289–297. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.janxdis.2013.03.001.

Greco, L. A., & Morris, T. L. (2002). Paternal child-rearing style and child social anxiety: Investigation of child perceptions and actual father behavior. Journal of Psychopathology and Behavioral Assessment, 4, 259–267. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1020779000183.

Grills-Taquechel, A. E., & Ollendick, T. H. (2012). Phobic and anxiety disorders in youth. Cambridge: Hogrefe & Huber Publishers.

Gulley, L. D., Hankin, B. L., & Young, J. F. (2016). Risk for depression and anxiety in youth: The interaction between negative affectivity, effortful control, and stressors. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 44, 207–218. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10802-015-9997-7.

Hirshfeld-Becker, D. R., Masek, B., Henin, A., Blakely, L. R., Pollock-Wurman, R. A., McQuade, J., et al. (2010). Cognitive behavioral therapy for 4- to 7-year-old children with anxiety disorders: A randomized clinical trial. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 78, 498–510. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0019055.

Hudson, J. L., Murayama, K., Meteyard, L., Morris, T., & Dodd, H. F. (2019). Early childhood predictors of anxiety in early adolescence. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 47, 1121–1133. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10802-018-0495-6.

Kagan, J., & Snidman, N. (1999). Early childhood predictors of adult anxiety disorders. Biological Psychiatry, 46, 1536–1541. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0006-3223(99)00137-7.

Kane, E. J., Braunstein, K., Ollendick, T. H., & Muris, P. (2015). Relations of anxiety sensitivity, control beliefs, and maternal over-control to fears in clinic-referred children with specific phobia. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 24, 2127–2134. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10826-014-0014-5.

Kendall, P. C., Safford, S., Flannery-Schroeder, E., & Webb, A. (2004). Child anxiety treatment: Outcomes in adolescence and impact on substance use and depression at 7.4-year follow-up. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 72, 276–287. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-006X.72.2.276.

Kiff, C. J., Lengua, L. J., & Bush, N. R. (2011a). Temperament variation in sensitivity to parenting: Predicting changes in depression and anxiety. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 39, 1199–1212. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10802-011-9539-x.

Kiff, C. J., Lengua, L. J., & Zalewski, M. (2011b). Nature and nurturing: Parenting in the context of child temperament. Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review, 14, 251–301.

Lawrence, P. J., Waite, P., & Creswell, C. (2019). Environmental factors in the development and maintenance of anxiety disorders. In Compton, S. N., Villabo, M. A., & Kristensen, H., (Eds.), Pediatric Anxiety Disorders (pp. 101–124). Amsterdam: Elsevier. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-12-813004-9.00006-2.

Lazarus, R. S., Dodd, H. F., Majdandžić, M., De Vente, W., Morris, T., Byrow, Y., et al. (2016). The relationship between challenging parenting behaviour and childhood anxiety disorders. Journal of Affective Disorders, 190, 784–791. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2015.11.032.

Lengua, L. J., & Long, A. C. (2002). The role of emotionality and self-regulation in the appraisal–coping process: Tests of direct and moderating effects. Journal of Applied Developmental Psychology, 23, 471–493. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0193-3973(02)00129-6.

Lerner, J. V., & Lerner, R. M. (1994). Explorations of the goodness-of-fit model in early adolescence. In W. B. Carey & S. C. McDevitt (Eds.), Prevention and early intervention (pp. 161–169). New York: Brunner/Mazel.

Liber, J. M., van Widenfelt, B. M., Goedhart, A. W., Utens, E. M., van der Leeden, A. J., Markus, M. T., & Treffers, P. D. (2008). Parenting and parental anxiety and depression as predictors of treatment outcome for childhood anxiety disorders: Has the role of fathers been underestimated? Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology, 37, 747–758. https://doi.org/10.1080/15374410802359692.

Lieb, R., Wittchen, H.-U., Höfler, M., Fuetsch, M., Stein, M. B., & Merikangas, K. R. (2000). Parental psychopathology, parenting styles, and the risk of social phobia in offspring: A prospective-longitudinal community study. Archives of General Psychiatry, 57, 859–866. https://doi.org/10.1001/archpsyc.57.9.859.

McLeod, B. D., Wood, J. J., & Weisz, J. R. (2007). Examining the association between parenting and childhood anxiety: A meta-analysis. Clinical Psychology Review, 27, 155–172. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2006.09.002.

Meesters, C., Muris, P., & van Rooijen, B. (2007). Relations of neuroticism and attentional control with symptoms of anxiety and aggression in non-clinical children. Journal of Psychopathology and Behavioral Assessment, 29, 149–158. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10862-006-9037-6.

Merikangas, K. R., He, J. P., Burstein, M., Swanson, S. A., Avenevoli, S., Cui, L., Benjet, C., Georgiades, K., & Swendsen, J. (2010). Lifetime prevalence of mental disorders in US adolescents: Results from the National Comorbidity Survey Replication–Adolescent Supplement (NCS-A). Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 49, 980–989. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaac.2010.05.017.

Milat, A. J., King, L., Bauman, A. E., & Redman, S. (2013). The concept of scalability: Increasing the scale and potential adoption of health promotion interventions into policy and practice. Health Promotion International, 28, 285–298.

Möller, E. L., Nikolić, M., Majdandžić, M., & Bögels, S. M. (2016). Associations between maternal and paternal parenting behaviors, anxiety and its precursors in early childhood: A meta-analysis. Clinical Psychology Review, 45, 17–33. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2016.03.002.

Muris, P., & Ollendick, T. H. (2002). The assessment of contemporary fears in adolescents using a modified version of the fear survey schedule for children-revised. Journal of Anxiety Disorders, 16, 567–584.

Murray, L., Creswell, C., & Cooper, P. J. (2009). The development of anxiety disorders in childhood: An integrative review. Psychological Medicine, 39, 1413–1423.

Ollendick, T. H. (1983). Reliability and validity of the revised fear survey schedule for children (FSSC-R). Behavior Research and Therapy, 21, 685–692.

Ollendick, T. H., & Grills, A. E. (2016). Perceived control, family environment, and the etiology of child anxiety – Revisited. Behavior Therapy, 47, 633–642. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.beth.2016.01.007.

Ollendick, T. H., Halldorsdottir, T., Fraire, M. G., Austin, K. E., Noguchi, R. J., Lewis, K. M., et al. (2015). Specific phobias in youth: A randomized controlled trial comparing one-session treatment to a parent-augmented one-session treatment. Behavior Therapy, 46, 141–155. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.beth.2014.09.004.

Parker, G., Tupling, H., & Brown, L. B. (1979). A parental bonding instrument. British Journal of Medical Psychology, 52, 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.2044-8341.1979.tb02487.x.

Pérez-Edgar, K., & Fox, N. A. (2005). Temperament and anxiety disorders. Child and Adolescent Psychiatric Clinics, 14, 681–706. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chc.2005.05.008.

Prinzie, P., Onghena, P., Hellinckx, W., Grietens, H., Ghesquière, P., & Colpin, H. (2003). The additive and interactive effects of parenting and children’s personality on externalizing behaviour. European Journal of Personality, 17, 95–117. https://doi.org/10.1002/per.467.

Putnam, S. P., Ellis, L. K., & Rothbart, M. K. (2001). The structure of temperament from infancy through adolescence. In A. Eliasz & A. Angleitner (Eds.), Advances in research on temperament (pp. 165–182). Lengerich: Pabst Science Publishers.

Rapee, R. M., Schniering, C. A., & Hudson, J. L. (2009). Anxiety disorders during childhood and adolescence: Origins and treatment. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology, 5, 311–341. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.clinpsy.032408.153628.

Rothbart, M. K. (2007). Temperament, development, and personality. Current Directions in, Psychological Science, 16, 207–212. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8721.2007.00505.x.

Salters-Pedneault, K., Roemer, L., Tull, M. T., Rucker, L., & Mennin, D. S. (2006). Evidence of broad deficits in emotion regulation associated with chronic worry and generalized anxiety disorder. Cognitive Therapy and Research, 30, 469–480. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10608-006-9055-4.

Schwartz, C. E., Snidman, N. C., & Kagan, J. (1999). Adolescent social anxiety as an outcome of inhibited temperament in childhood. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 38, 1008–1015. https://doi.org/10.1097/00004583-199908000-00017.

Shaffer, D., Gould, M. S., Brasic, J., Ambrosini, P., Fisher, P., Bird, H., & Aluwahlia, S. (1983). A children's global assessment scale (CGAS). Archives of General Psychiatry, 40, 1228–1231.

Silverman, W. K., & Albano, A. M. (1996). Anxiety disorders interview schedule for DSM-IV (child and parent versions). San Antonio: Psychological Corporation.

Silverman, W. K., & Moreno, J. (2005). Specific phobia. Child and Adolescent Psychiatric Clinics, 14, 819–843. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chc.2005.05.004.

StataCorp. (2017). Stata statistical software: Release 15. College Station: StataCorp LLC.

Thomas, A., Chess, S., & Birch, H. G. (1968). Temperament and behaviour disorders in children. New York: New York University Press.

van Der Bruggen, C. O., Stams, G. J. J., & Bögels, S. M. (2008). Research review: The relation between child and parent anxiety and parental control: A meta-analytic review. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 49, 1257–1269. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-7610.2008.01898.x.

Verhoeven, M., Bögels, S. M., & van der Bruggen, C. C. (2012). Unique roles of mothering and fathering in child anxiety; moderation by child’s age and gender. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 21, 331–343. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10826-011-9483-y.

Vervoort, L., Wolters, L. H., Hogendoorn, S. M., Prins, P. J., de Haan, E., Boer, F., & Hartman, C. A. (2011). Temperament, attentional processes, and anxiety: Diverging links between adolescents with and without anxiety disorders? Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology, 40, 144–155. https://doi.org/10.1080/15374416.2011.533412.

Wagner, A., Lecavalier, L., Arnold, L. E., Aman, M. G., Scahill, L., Stigler, K. A., Johnson, C. R., McDougle, C. J., & Vitiello, B. (2007). Developmental disabilities modification of the Children’s global assessment scale. Biological Psychiatry, 61, 504–511. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biopsych.2007.01.001.

Wood, J. J., McLeod, B. D., Sigman, M., Hwang, W., & Chu, B. C. (2003). Parenting and childhood anxiety: Theory, empirical findings, and future directions. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 44, 134–151. https://doi.org/10.1111/1469-7610.00106.

Funding

This study was funded by the National Institute of Mental Health, Grant R01MH074777.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

NCH contributed to hypothesis generation and helped write the manuscript. JAB contributed to data analysis and helped write the manuscript. THO secured the relevant funding for this project, oversaw data collection, and helped write the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Ethical Approval

All procedures performed in this study were in accordance with the ethical standards of the overseeing Institutional Review Board and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments.

Informed Consent

Informed consent was obtained from all participants included in the study.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Capriola-Hall, N.N., Booker, J.A. & Ollendick, T.H. Parent- and Child-Factors in Specific Phobias: The Interplay of Overprotection and Negative Affectivity. J Abnorm Child Psychol 48, 1291–1302 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10802-020-00662-3

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10802-020-00662-3