Abstract

The objective of this study is twofold. First, it investigates the association between technological change and over-education by analysing incidence of over-education and its change across skill-based and task-based job categories. Second, it compares countries with different employment change pattern—mainly upgrading and polarizing—to establish a link between employment polarization and over-education. Using data from European Labour Force Survey covering the period from 1999 to 2007, the paper analyses four countries of Europe—Germany, Spain, Sweden and UK. The results suggest higher incidence of over-education in polarized countries—Spain and UK as compared to countries with a somewhat upgrading pattern of employment change—Germany and Sweden. It also reveals that in Spain and UK, over-education is prominent and increasing over time in the low-skill jobs which are mostly non-routine manual in nature, while Germany and Sweden have more over-educated workers in middle skilled routine and high skilled analytical jobs. I find similar results in both descriptive and job fixed effects regressions.

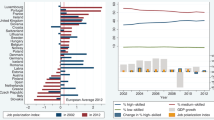

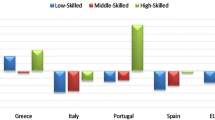

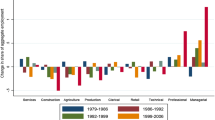

Source Author’s own calculation from the JOBS database

Source Author’s own calculation from the JOBS database

Source Author’s own calculation from the JOBS database

Source Author’s own calculation from the JOBS database

Source Author’s own calculation from the JOBS database

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

SBTC predicts the use of computer-based technology to complement skilled jobs and thus to increase monotonically the demand for high-skill workers relative to low-skill workers. TBTC (which is also referred as RBTC, routine-biased technical change) on the other hand argues that use of computer-based technology is most likely to replace middle-skill jobs with routine tasks. According to the TBTC hypothesis, while machine can replace the methodical jobs, the non-routine jobs located in very bottom and top of the occupational hierarchy cannot be substituted by technology. For a vivid discussion on SBTC and TBTC please refer to Fernandez-Macias and Hurley (2016) for further reading.

Literature of polarization and technological change has interchangeably used the terms low-skill, low-paid or bad jobs and high-skill, high-paid or good jobs while explaining the structural change across the job or occupational hierarchy. These terms have also been used in this paper to refer job or occupational hierarchy.

The concept of over-education was first explored by Richard Freeman in his book ‘The Overeducated American’ in 1976 (Freeman 1976). In this book Freeman focuses on over education, the situation where worker’s skill or education level exceeds the level of skills or education required by the employer to obtain or perform the job. There can also be a situation where workers’ actual levels of skills or education fall short of the requirement. This situation is called under-education or under-skilling. Given the higher level of participation in tertiary education in developed countries, over-education has been a major concern for the past few decades.

The literature (Duncan and Hoffman 1981; Hartog and Oosterbeek 1988; Green et al. 2002; Chevalier and Lindley 2009) on over-education has mushroomed with a little attention to the phenomenon of under-education. Nonetheless, many studies highlight the fact that under-education is a temporary phenomenon and can be overcome with experience while over-education can be a long term problem (Green and McIntosh 2007).

Bernardi and Garrido (2008) and Oesch and Rodriguez-Menes (2011) find a polarizing employment structure in Spain unlike Fernandez-Macias et al. (2012). Tåhlin (2007) and Dustmann et al. (2009) find an occupational upgrading in Germany while Spitz-Oener (2006) finds a job polarization for Germany. In a recent study Adermon and Gustavsson, (2015) find job polarization in Sweden during the 90s and the 2000s contradicting the findings of Fernandez-Macias et al. (2012) who observe an occupational upgrading in Sweden. The common fact which has emerged from all of the studies is that there has been a massive job upgradation in advanced countries of Europe.

The JOBS project is carried out by a team at the European Foundation for the Improvement of Living and Working Conditions (Eurofound). One of the objectives of this project is to construct data sets suitable to conduct analysis at ‘job’ level. For more details on the JOBS project and database see Fernandez-Macias et al. (2012). Transformation of the Employment Structure in the EU and USA, 1995–2007. Palgrave Macmillan.

The words job and occupation have been interchangeably used throughout the paper.

After dropping small cells jobs, the final sample consists of around 1100 jobs in Germany, 970 jobs in Spain, 680 to 930 jobs in Sweden and almost 1050 jobs in UK across the years. However, the balanced panel has 847 jobs in Germany, 723 jobs in Spain, 540 jobs in Sweden and 785 jobs in the United Kingdom.

The 2002 ESES was used for estimating median hourly wages for each job in each country. But this survey does not cover the public sector and does not provide a two-digit disaggregation of the manufacturing sector, so the European Survey on Income and Living Conditions data from the year 2005 has been used to complement. A detailed explanation of the JOBS data and the Job-level approach has been provided by Fernandez-Macias (2012).

Routine occupations include both routine manual and routine cognitive occupations. A Table with two digit ISCO codes under each of these task-based categories is presented in Appendix Table 8.

The period 1999 to 2007 is used for the job-education mismatch analysis as the data before 1999 have some fluctuations in the education variable.

The JOBS data also have detailed education variable taking 1 to 6 values of International Standard Classification of Education (ISCED). The 6 levels are: Level 1—Primary education or first stage of basic; Level 2—Lower secondary or second stage of basic education, Level 3—(Upper) secondary education; Level 4—Post-secondary non-tertiary education; Level 5—First stage of tertiary education; Level 6—Second stage of tertiary education. However, the broad three level education variable is used for the analysis since there are few observations (or no observation for some years) in the ISCED-1, ISCED-4 and ISCED-6. The whole analysis has also been done using the detailed education variable and the results are almost similar to that of the broad education variable.

Some jobs are very different in terms of the technology used or the tasks performed under them to produce output.

A summary table showing mean and standard deviation of dependent and all the explanatory variables are presented in Table 4.

References

Acemoglu D (1999) Changes in unemployment and wage inequality: an alternative theory and some evidence. Am Econ Rev 89:1259–1278

Acemoglu D, Autor DH (2011) Skills, tasks and technologies: implications for employment and earnings. In: Ashenfelter O, Card DE (eds) Handbook of labor economics, vol 4. Elsevier, Amsterdam, pp 1043–1171

Adermon A, Gustavsson M (2015) Job polarization and task-biased technological change: evidence from Sweden, 1975–2005. Scand J Econ 117(3):878–917

Alba-Ramirez A (1993) Mismatch in the Spanish labour market. J Hum Resour 28(2):259–278

Autor DH, Dorn D (2013) The growth of low-skill service jobs and the polarization of the US labor market. Am Econ Rev 103(5):1553–1597

Autor DH, Lawrence FK, Melissa SK (2006) The polarization of the US labor market. Am Econ Rev 96(2):189–194

Baur TK (2002) Educational mismatch and wages: a panel analysis. Econ Educ Rev 21(2002):221–229

Bernardi F, Garrido L (2008) Is there a new service proletariat? Post-industrial employment growth and social inequalit in Spain. Eur Sociol Rev 24:299–313

Buchel F (2002) The effects of overeducation on productivity in Germany—The Firms’ Viewpoint. Econ Educ Rev 21(2002):263–275

Dolton P (2001) Over-education in the graduate labour market: some evidence from alumni data," CEE Discussion Papers 0009, Centre for the Economics of Education, LSE

Chevalier A, Lindley J (2009) Over-education and Skills of UK Graduates. J R Stat Soc Part 2 172:307–337

Duncan J, Hoffman S (1981) The incidence and wage effects of over-education. Econ Educ Rev 1(1):75–86

Dustmann C, Ludsteck J, Schonberg U (2009) Revisiting the German Wage Structure. Quart J Econ 124:843–881

Esteban J, Gradin C, Ray D (2007) An extension of a measure of polarization, with an application to the income distribution of five OECD countries. J Econ Inequal 5(1):1–19

Fernandez-Macias E (2012) Job polarization in Europe? changes in the employment structure and job quality, 1995–2007. Work Occup 39:157–182

Fernández C, Ortega C (2008) Labor market assimilation of immigrants in Spain: employment at the expense of Bad Job-matches? Span Econ Rev 10(2):83–107

Fernandez-Macias E, Hurley J (2016) RBTC and job polarization in Europe. Socioecon Rev 1–23. doi:10.1093/ser/mww016

Fernandez-Macias E, Hurley J, Storrie D (2012) Transformation of the Employment Structure in the EU and USA, 1995–2007. Palgrave Macmillan, Basingstoke

Freeman R (1975) Over investment in college training. J Hum Resour 10(3):287–311

Freeman R (1976) The overeducated American. Academic Press, New York

Goos M, Manning A (2007) Lousy and lovely jobs: the rising polarisation of work in Britain. Rev Econ Stat 89(1):118–133

Goos M, Manning A, Salomons A (2009) Job polarization in Europe. Am Econ Rev Pap Proc 99(2):58–63

Goos M, Manning A, Salomons A (2014) Explaining job polarization: routine-biased technological change and offshoring. Am Econ Rev 104(8):2509–2526

Green F, McIntosh S (2007) Is there a genuine under-utilisation of skills amongst the over-qualified? Appl Econ 39:427–439

Green F, Zhu Y (2008) Over qualification, job dissatisfaction, and increasing dispersion in the returns to graduate education, Kent: University of Kent, Department of Economics (Discussion papers KDPE 08/03)

Green F, McIntosh S, Vignoles A (2002) The utilization of education and skills: evidence from Britain. Manch Sch 70:792–811. doi:10.1111/1467-9957.00325

Halaby CN (1994) Over education and skill mismatch. Sociol Educ 67(1):47–59

Hall PA, Soskice D (2001) Varieties of capitalism: the institutional foundations of comparative advantage. Oxford University Press, Oxford

Hartog J (2000) Over-education and earnings: where are we, where should we go? Econ Educ Rev 19(2):131–148

Hartog J, Oosterbeek H (1988) Education, allocation and earnings in the Netherlands: over schooling? Econ Educ Rev 7(2):185–194

Kiker B, Santos M, Mendes OM (1997) Over-education and under-education: evidence for Portugal. Econ Education Review 16(2):111–125

Korpi T, Tahlin M (2009) Educational mismatch, wages, and wage growth: overeducation in Sweden, 1974–2000. Labour Econ 16(2009):183–193

Kupets O (2016) Education-job mismatch in Ukraine: too many people with tertiary education or too many jobs for low-skilled? J Comp Econ 44(2016):125–147

Leuven E, Oosterbeek H (2011) Over-education and mismatch in the labour market. IZA Discussion Paper No. 5523

Muñoz de Bustillo R, Antón J-I (2012) Immigration and labour market segmentation in the European Union. Transform Employ Struct EU and USA 1995–2007:111–146

Nordin M, Persson I, Rooth DO (2010) Education–occupation mismatch: is there an income penalty? Econ Educ Rev 29(2010):1047–1059

Oesch D, Rodriguez-Menes J (2011) Upgrading or polarization? occupational change in Britain, Germany, Spain and Switzerland, 1990–2008. Socio-Econ Rev 9:503–531

Papke LE, Wooldridge JM (1996) Econometric methods for fractional response variables with an application to 401 (K) plan participation rates. J Appl Econom 11(6):619–632

Piracha M, Vadean F (2013) Migrant Educational Mismatch and the Labour Market. In: Constant A, Zimmermann K (eds) International handbook on the economics of migration. Edward Elgar, Cheltenham

Quintini G (2011) Over-qualified or under-skilled: a review of existing literature, OECD social, employment and migration working papers, no. 121. OECD Publishing, Paris. doi:10.1787/5kg58j9d7b6d-en

Sanroma E, Ramos R, Simon H (2008) The Portability of human capital and immigration assimilation: evidence from Spain, IZA discussion paper no 3649

Sloane PJ (2003) Much ado about nothing? what does the over-education literature really tell us? In: Buchel F, de Grip A, Mertens A (eds) Over-education in Europe. Edward Elgar, Cheltenham, pp 11–49

Sloane PJ, Battu H, Seaman PT (1999) Overeducation undereducation and the British labour market. Appl Econ 31(11):1437–1453

Spitz-Oener A (2006) Technical change, job tasks, and rising educational demands: looking outside the wage structure. J Labor Econ 24(2):235–270

Tåhlin M (2007) Skills and wages in European labour markets: structure and change. In: Gallie D (ed) Employment regimes and the quality of work. Oxford University Press, Oxford, pp 35–76

Wright EO, Dwyer R (2003) The patterns of job expansions in the USA: a Comparison of the 1960s and 1990s. Socio-Econ Rev 1:289–325

Acknowledgements

I thank Enrique Fernandez-Macias, Rafael Muñoz de Bustillo, Jose Ignacio-Anton, Tobias Braendle and Soham Sahoo for their valuable comments and feedback which helped enormously to improve the paper. I also thank the participants of the workshops at Eurofound, NOeG-SEA conference and Young Economist’s Meeting, 2016 for their helpful comments. The author acknowledges the financial support of the Eduworks Marie Curie Initial Training Network Project (PITN-GA-2013-608311) of the European Commission’s 7th Framework Program.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Sarkar, S. Employment polarization and over-education in Germany, Spain, Sweden and UK. Empirica 44, 435–463 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10663-017-9372-8

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10663-017-9372-8