Abstract

We performed an experimental investigation to assess whether the “restricted auction” mechanism proposed by Berkovitch, Israel and Zender in 1997 works effectively as an optimal bankruptcy law or not. An optimal bankruptcy law is a commitment device that implements efficient choices both before (ex ante) and after (ex post) financial distress, even if moral hazard is binding. We designed an experiment focused on ex ante efficiency and we found that the restricted auction mechanism was able to direct an optimal amount of effort toward entrepreneurial activities. This result confirms the theoretical predictions. Nonetheless, we found that under a plain unrestricted auction mechanism our experimental subjects chose to allocate into their firms a larger amount of effort than that predicted by theory. Although difficult to justify on theoretical grounds, this experimental evidence is robust. Our behavioral interpretation is that this result is due to “moral sentiments”, such as the natural propensity of subjects toward socially desirable behaviors. In fact, we show that it vanishes once these motives are removed.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

This informational structure is peculiar since it implies that both the investor and the entrepreneur have the same amount of information. On the contrary, outside investors have no information about the profitability of the firm.

Also outside investors know L.

The right of refusal of the investor is a guarantee against the entrepreneur asking for bankruptcy procedures in case the firm is not financially distressed. The restriction imposed on the investor allows the entrepreneur to win the auction (he has more information than outside bidders about the future cash flow) and obtain all the surplus. If the investor was allowed to bid, he would bid more than the entrepreneur given a higher reservation value (due to the initial investment).

Subjects were recruited among undergraduate students of LUISS- Guido Carli University of Rome.

We adopted a screening technique called Multiple Price List (MPL) to elicit risk attitudes Miller et al. (1969), Schubert et al. (1999), Barr and Packard (2002), and Holt and Laury (2002, 2005). In particular, we followed the procedure adopted by Holt and Laury. The experimental literature is almost unanimous on the fact that MPL provides a relatively transparent procedure to elicit risk attitudes. In fact, subjects rarely get confused about the incentives to respond truthfully.This method allowed us to select 150 subjects who actually behaved as risk neutral.

Samples performing under the two treatments are independent.

This procedure resembles a BDM mechanism. Noussair et al. (2004) show that a BDM mechanism and a Vickrey auction are equivalent to truthful revelation of individuals’ willingness to pay apart from some behavioral differences related to sufficient practice and appropriate training.

It is important to point out that in both cases choices are not statistically different at a 5% significance level. However, the behavior of experimental subjects under RE is important to exclude that they chose lotteries simply by similarity between Phase 0 and either Phase 1 or 2.

Since the the experimental design is complex, we asked our experimental subjects to provide comments about the difficulties that they faced during the experiment. The great majority of them (more than 80%) say that they understood perfectly the trade-off implied by their choices. Another way to check whether the experimental subjects understood the experiment is to look at the bids that they made in the auction environment: again, 80% of the subjects made bids that are consistent with an optimal strategic behavior.

In a related paper, Di Cagno et al. (2004) found different results in terms of correspondence between theoretical predictions and experimental choices. These difference is probably due to the fact that in our experiment subjects have been allowed to train while in Di Cagno et al they were not.

Actually, there is another possible explanation related to possible order effects (Harrison et al. 2005). However, we are not able to control for such effects because it would not make any sense to switch the sequential order between Phase 0 and Phase 2. Moreover, the results of the follow-up experiment described in the next section seem to exclude such effects.

One possible criticism to our procedure is that endogenous sample selection may occurr, that is it might be the case that only subjects who performed well in the initial experiment decided to show up again. If this was the case, our results could have been affected by some sort of sample selection bias; in particular, we could have observed our experimental subjects replicating in the follow-up experiment their initial (successful) behavior. However, as it will be shown later on, our experimental results prove that the decisions taken by our experimental subjects in the follow-up experiment differ significantly from those taken in the initial experiment; hence, sample selection bias does not seem to have kicked in.

With respect to our first experiment, we deleted the Phase 0 treatment. Again, we decided to save on money because there was no need to make the subjects acquainted with the experimental software that they had already seen in the initial experiment.

References

Aghion, P., Hart, O. D., & Moore, J. (1992). The economics of bankruptcy reform. Journal of Law, Economics and Organization, 8, 423–446.

Andersen, S., Harrison, G. W., Igel Lau, M., & Rutstrom, E. E. (2006). Elicitation using multiple price list formats. Experimental Economics, 9, 383–405.

Barr, A., & Packard, T. (2002). Revealed preference and self insurance: Can we learn from the self employed in Chile? Policy Research Working Paper, World Bank.

Bebchuk, L. A. (1988). A new approach to corporate reorganization. Harward Law review, 101, 775–804.

Berkovitch, E., & Israel, R. (1999). Optimal bankruptcy law across different economic systems. Review of Financial Studies, 41 487–497.

Berkovitch, E., Israel, R., & Zender, J. F. (1997). Optimal bankruptcy law and firm-specific investments. European economic Review, 33, 441–464.

Bowles, S., & Hwang, S. H. (2008). Social preferences and public economics: Mechanism design when social preferences depend on incentives. Working Paper.

Camerer, C. (2003). Behavioral game theory: Experimental studies on strategic interaction. Princeton University Press.

Cardenas, J. C., Stranlund, J. K., & Willis, C. E. (2000). Local environment control and institutional crowding out. World Development, 28, 1719–1733.

Di Cagno, D., Sabato, V., & Spallone, M. (2004). Bankruptcy laws: Optimal incentives to entrepreneurs. Economia, Società e Istituzioni, 16, 171–199.

Falk, A., & Kosfeld, M. (2006). The hidden costs of control. American Economic Review, 96, 1611–1630.

Fehr, E., Gaechter, S., & Schmidt, K. M. (2007). Fairness and contract design. Econometrica, 75, 121–154.

Fehr, E., & List, J. (2004). The hidden costs and returns of incentives: Trust and trustworthiness among ceo’s. Journal of the European Economic Association, 2, 743–771.

Fehr, E., & Rockenbach, B. (2003). Detrimental effects of sanctions on human altruism. Nature, 422, 137–140.

Gaechter, S., & Riedl, A. (2004). Dividing justly in bargaining problems with claims. Tinbergen Institute Discussion Paper.

Gaechter, S., & Riedl, A. (2005). Moral property rights in bargaining with infeasible claims. Management Science, 51, 249–263.

Gneezy, U., & Rustichini, A. (2000). A fine is a price. Journal of Legal Studies, 29, 1–17.

Harrison, G. W., Johnson, E., McInnes, M. M., & Rutstrom, E. E. (2005). Risk aversion and incentive effects: Comment. American Economic Review, 95, 897–901.

Herrero, C., Moreno-Ternero, J. D., & Ponti, G. (2002). An experiment on bankruptcy. Working Paper.

Holt, C., & Laury, S. K. (2002). Risk aversion and incentive effects. American Economic Review, 92, 1644–1655.

Holt, C., & Laury, S. K. (2005). Risk aversion and incentive effects: New data without order effect. American Economic Review, 95, 902–912.

Jensen, M. (1991). Corporate control and the politics of finance. Journal of Applied Corporate Finance, 4, 13–33.

Kirby, K. N., & Marakovic, N. N. (1996). Delay-discounting probabilistic rewards: Rates decrease as amounts increase. Journal of Experimental Psychology, 3, 100–104.

Kirby, K. N., Petry, N. M., & Bickel, W. K. (1999). Heroin addicts have higher discount rates for delayed rewards than non-drug using controls. Journal of Experimental Psychology, 128, 78–87.

Miller, L., Meyer, D. E., & Lanzetta, J. T. (1969). Choice among equal expected value alternatives: Sequential effects of winning probability level on risk preferences. Journal of Experimental Psychology, 79, 419–423.

Noussair, C., Robin, S., & Ruffieux, B. (2004). Revealing consumers’ willingness-to-pay: A comparison of the BDM mechanism and the Vickrey auction. Journal of Economic Psychology, 25, 725–741.

Schubert, R., Brown, M., Gysler, M., & Brachinger, H. W. (1999). Financial decision-making: Are women really more risk-averse? American Economic Review (Papers and Proceedings), 89, 381–385.

White, M. J. (2005). Economic analysis of corporate and personal bankruptcy law. NBER Working Paper.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Appendix: instructions

Appendix: instructions

1.1 Introduction

The instructions are simple. If you follow them carefully you can earn up to 50,000 Experimental Credits (25 Euros).

The experiment consists of 2 different phases. In each phase the computer will work out your payoff. At the end of the experiment, you will draw one of the 2 phases and you will be paid immediately and in cash the money you made in the drawn phase.

Pay attention: your gain in each phase depends on your choices.

Thanks for your participation.

If you have any doubt, do not hesitate to contact the experimenters for further information.

1.2 Phase 0

Phase 0 consists of 3 ROUNDS.

In each ROUND, the computer shows you 6 lotteries sequentially. Each lottery is represented by three colored areas. The possible outcomes of each lottery are displayed on your screen (and in the payoff tables on your desk) (Fig. 5).

You have to choose the lottery you prefer to play. The computer will force you to scroll all lotteries before making your choice.

After your choice, you move to the next ROUND. Each ROUND works in the same way.

At the end of the third ROUND, one ROUND among the three you played will be randomly selected and the lottery you chose in that ROUND will be played for real: the computer swings a indicator over the three areas representing that lottery and works out your payoff according to the point where the indicator stops (Fig. 6).

Phase 0—indicator. Translation: “Per scorrere…”: To see the lotteries use arrows or select ENTER to move forward and BACK SPACE to move backward. To look at a single lottery press F1,…, F6. To choose a lottery press F12. “L’esperimento…”: The experiment is over. Your payoff is 3,500 EC. “Per maggiori…”: For further information press I

Take a closer look at the payoffs’ tables. Notice that, if the indicator stops at any point of the area where the payoff is the payoff of the outside option (blue area), you get a fixed payoff which is different from lottery to lottery; if the indicator stops at any point of the area where the payoff is the Nash bargaining payoff (red area), again you get a fixed payoff which is different from lottery to lottery; if the indicator stops in the area where the payoff is the realized cash flow (yellow area), you get a payoff that depends on the exact point where the indicator stops. This payoff is bounded between a minimum and a maximum, as you can see in the payoffs’ table. The minimum and maximum payoffs are different from lottery to lottery.

Before the experiment starts, you are required to play with Phase 0 twice in order to get acquainted with the software and to check the consequences of your choices in terms of payoffs.

1.3 Phase 1

You are an entrepreneur who has already run a project, financed by a bank (the computer). The final outcome of the investment is uncertain and depends partly on your effort and partly on your luck. You have to decide how much effort to put in your firm, considering the three different final situations which may occur (Fig. 7).

1.3.1 Final situations

3 final situations may occur:

-

1.

Your firm can turn out to be NOT ECONOMICALLY VIABLE and IN FINANCIAL DISTRESS (i.e., it does not generate any wealth and it is not able to pay back its debt);

-

2.

Your firm can turn out to be ECONOMICALLY VIABLE, but IN FINANCIAL DISTRESS (i.e., it generates wealth, but it is not able to pay back its whole debt);

-

3.

Your firm can turn out to be both ECONOMICALLY and FINANCIALLY VIABLE.

In the first situation, your firm goes bankrupt and you come back home with a payoff (blue area in the payoffs’ table) that depends on the level of effort H you have chosen. The liquidation value of your firm is 90,000 Experimental Credits.

In the third situation, your firm is healthy and you come back home with a payoff which is bounded between a minimum and a maximum (yellow area in the payoffs’ table). The minimum and the maximum depend on the level of effort H you have chosen.

In the second situation, your firm is auctioned off and you have to bid for it (red area in the payoffs’ table).

1.3.2 The auction

It is a SECOND-PRICE SEALED-BID AUCTION that you and an outside investor (played by the computer) participate. The bank that financed your project is not allowed to participate the auction. The auction mechanism is simple and the computer will tell you what to do at any stage (Fig. 8).

Phase 1—auction. Translation: “Per scorrere…”: To see the lotteries use arrows or select ENTER to move forward and BACK SPACE to move backward. To look at a single lottery press F1,…, F6. To choose a lottery press F12. “Dopo aver…”: After you made your bid press ENTER. “Il tuo…”: Your competitor bids EC…. “Digita…”: Input your bid. “Per maggiori…”: For further information press I

First of all, the computer collects the bid of the outside investor. After that, it asks you to type your bid. Then, the computer reveals the bids and announces the winner, i.e. the one who made the highest bid. The winner pays for the firm the price offered by the other bidder, which is the SECOND PRICE. For instance, if you bid 100,000 Experimental Credits and the outside investor bids 50,000 Experimental Credits, you win the auction and the price you pay for the firm is 50,000 Experimental Credits.

If you win the auction, you earn a payoff which is bounded between a minimum and a maximum depending on the level of effort H you have chosen (“MIN” and “MAX” of “WON” columns of the red area in the payoffs’ table). If you do not win the auction, you earn a fixed payoff (“LOST” column of the red area in the payoffs’ table).

1.3.3 The choice of the entrepreneurial effort

The computer shows you 6 screens, one for each level of H (the level of effort you must choose to put into your firm). Each screen consists of 3 colored areas that represent the possible outcomes of your choice of H. These outcomes are displayed in the attached payoffs’ tables.

After you have seen all the screens at least once, you can choose the level of H you prefer.

After you chose a certain H, the computer shows you the corresponding screen. Then, it swings a indicator over the three colored areas representing your choice of H and computes your payoff according to the point where the indicator stops.

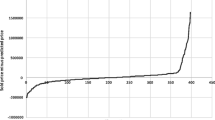

Take a closer look at the payoffs’ tables. Notice that, if the indicator stops at any point of the area where the payoff is the outside option payoff (blue area), you get a fixed payoff which is different for each H. If the indicator stops at any point of the area where the payoff is the Nash bargaining payoff (red area), you participate the auction and get a payoff which depends both on whether you have or you have not won the auction, and the H you have chosen. If the indicator stops in the area where the payoff is the realized cash flow (yellow area), you get a payoff which is bounded between a minimum and a maximum. Notice that the minimum and maximum payoffs are different for each H. For instance, if you have chosen H equal to 5,000 and the indicator stops in the blue area, you get 2,500 Experimental Credits; if the indicator stops in the red area and you have not won the auction, you get 2,500 Experimental Credits; if the indicator stops in the red area and you have won the auction, you get a payoff from a minimum of 2,500 Experimental Credits up to 22,500 Experimental Credits; if the indicator stops in the yellow area, you get from a minimum of 2,500 Experimental Credits up to a maximum of 45,000 Experimental Credits.

1.4 Phase 2

Instructions for Phase 2 are the same as those for Phase 1, except for the fact that experimental subjects are now advised that the bank is not only aware of the liquidation value of the firm, but also of its output.

From this difference the new description of the auction mechanism follows.

The following sentence:

-

“It is a SECOND-PRICE SEALED-BID AUCTION that you and an outside investor (played by the computer) participate.”

is replaced with:

-

“It is a SECOND-PRICE SEALED-BID AUCTION that you and the bank that financed your project (played by the computer) participate.”

Notice that Phase 2 payoffs are the same as those for Phase 1.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Di Cagno, D., Spallone, M. An experimental investigation on optimal bankruptcy laws. Eur J Law Econ 33, 205–229 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10657-010-9161-3

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10657-010-9161-3